Nenano

| Byzantine culture |

|---|

|

Phthora nenano (Medieval Greek: φθορὰ νενανῶ, also νενανὼ) is the name of one of the two "extra" modes in the Byzantine Octoechos—an eight-mode system, which was proclaimed by a synod of 792. The phthorai nenano and nana were favoured by composers at the Monastery Agios Sabas, near Jerusalem, while hymnographers at the Stoudiou-Monastery obviously preferred the diatonic mele.

The phthora nenano as part of the Hagiopolitan octoechos

[edit]Today the system of eight diatonic modes and two phthorai ("destroyers") is regarded as the modal system of Byzantine chant, and during the eighth century it became also model for the Latin tonaries—introductions into a proper diatonic eight mode system and its psalmody, created by Frankish cantores during the Carolinigian reform.[1] While φθορά νενανῶ was often called "chromatic", the second phthora was named "nana" (gr. φθορά νανὰ) and called "enharmonic", the names were simply taken from the syllables used for the intonation (enechema). The two phthorai were regarded as two proper modes, but also used as transposition or alteration signs. Within the diatonic modes of the octoechos they cause a change into another (chromatic or enharmonic) genus (metavoli kata genos).[2]

The earliest description of phthora nenano and of the eight mode system (octoechos) can be found in the Hagiopolites treatise which is known in a complete form through a fourteenth-century manuscript.[3] The treatise itself can be dated back to the ninth century, when it introduced the book of tropologion, a collection of troparic and heirmologic hymns which was ordered according to the eight-week cycle of the octoechos.[4] The first paragraph of the treatise maintains, that it was written by John of Damascus.[5] The hymns of the tropologion provided the melodic models of one mode called echos (gr. ἦχος), and models for the phthora nenano appeared in some mele of certain echoi like protos and plagios devteros.

—Hagiopolites (§2)[6]

The author of the treatise wrote obviously during or after the time of Joseph and his brother Theodore the Studite, when the use the mesos forms, phthorai nenano and nana were no longer popular. The word "mousike" (μουσική) referred an autochthonous theory during the 8th century used by the generation of John of Damascus and Cosmas of Maiuma at Mar Saba, because it was independent from ancient Greek music.[7] But it seems that it was regarded as inappropriate to use these phthorai for the hymn melodies composed by Joseph and other hymns composed since the ninth century, since they must have preferred the diatonic octoechos based on the kyrios and the plagios instead of the mesoi.

The concept of phthora in the Hagiopolites was less concerned that the Nenano and Nana were somehow bridges between the modes. As an introduction of the tropologion it had to integrate the mele composed in these phthorai within the octoechos order and its weekly cycles. Since they had their own mele and compositions like the other echoi, they were subordinated to the eight diatonic echoi according to the pitches or degrees of the mode (phthongoi) of their cadences.

{{Text and translationφθοραὶ δὲ ὠνομασθήσαν, ὅτι ἐκ τῶν ἰδίων ἤχων πᾶρχονται, τελειοῦνται δὲ εἰς ἑτέρων ἤχων φθογγὰς αἱ θέσεις αὐτῶν καὶ τὰ ποτελέσματα. |They were called Phthorai (i.e. destroyers), because they begin from their own Echoi, but the thesis of their cadences and formulas are on notes (phthongoi) from other Echoi.[8] |Hagiopolites (§34)}}

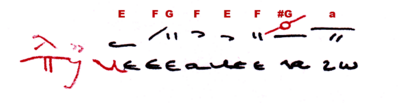

They had to be classified according to a certain echos of the eight-week cycle by adding the intonation "nenano" to the intonation of the main diatonic echos (usually abbreviated by a modal signature). For example, the intonation formula of echos plagios devteros (E) could be followed by the intonation of nenano which leads to the echos protos (a), as a kind of "mesos devteros", which lies in between the finalis of the kyrios (b natural) and the one of its plagios (E). Usually the diatonic kyrios protos (a) could end on its plagios (D) in the diatonic genus, but the chromatic phthora nenano makes it end in the plagios devteros (E).

The use of phthora nenano in the psaltic art

[edit]In the period of the psaltic art (gr. ψαλτικὴ τέχνη, "the art of chant", 1261–1750) the Late Byzantine Notation used four additional phthorai for each mode, including the eight diatonic echoi, in order to indicate the precise moment of a transposition (metavoli kata tonon).[9] The former system of sixteen echoi (4 kyrioi, 4 plagioi, 4 mesoi, and 4 phthorai) which was still used in the old books of the cathedral rite (asmatikon, kontakarion, etc.), was replaced by the Hagiopolitan octoechos and its two phthorai. The new book akolouthiai which replaced the former book and established a mixed rite in Constantinople, introduced into eight diatonic echoi and two phthorai. In rather soloistic chant genres, the devteros echoi were turned into the chromatic genus by an abundant use of the phthora nenano.[10] Hence, it became necessary to distinguish between the proper echos and its phthora, nenano and nana as "extra modes", and their use for temporary changes within the melos of a certain diatonic echos.

The use of six phthorai for all of the ten Hagiopolitan echoi

[edit]In his theoretical treatise about psaltic art and in response to the "wrong ideas" that some singers already had some years after the conquest of Constantinople (1458), the famous Maïstoros Manuel Chrysaphes introduced not only into the two phthorai nenano and nana, but also into four phthorai which bind the melos to the diatonic echoi of protos, devteros, tritos, and tetartos.

All six phthora, two of them belonged to the phthora nenano (the phthora of nenano and the one of plagios devteros), could dissolve the former melos and bind it to the melos of the following echos defined by the next medial signature. The diatonic phthora was no longer the destruction of the diatonic modes and its genus, melos, and its tonal system, it could change each mode and its finalis into another echos by a simple transposition. Hence, the list of phthorai mentioned in each Papadikai, was simply a catalogue of transposition signs, which were written over that neume where the transposition has to be done.

Phthora nenano and the plagal second echos

[edit]In that respect phthora nenano, as well as nana, stuck out, because within their own melos they were both directed to certain other echoi:

—Manuel Chrysaphes, Lampadarios at the Byzantine court On the theory of psaltic art

It was the psaltic art itself which moved the phthongos of plagios devteros to the one of plagios protos. It is possible, that the phthora of plagios devteros was needed to change again into diatonic genus. According to the New Method (since 1814) echos plagios devteros was always chromatic and based on the phthongos of echos protos, memorised as πα. This was Chrysanthos' way to understand Manuel Chrysaphes—probably a contemporary way, since the 17th-century Papadike introduced a seventh phthora for plagios protos.

According to the rules of psaltic art phthora nenano could connect the phthongoi devteros and protos as well as protos and tetartos, as can be seen from the solfège diagram called the "parallage of John Plousiadenos" (see the first X in the first row around the centre of the enechema of phthora nenano).

Despite this possibility Manuel Chrysaphes insisted, that phthora nenano and its chromatic melos has always to be resolved as plagios devteros, any other echos would be against the rules of psaltic art. The living tradition today still respects this rule, since phthongos of the plagios devteros (πλβ᾽) has become the same like plagios protos (πλα᾽): πα (D).

The early Persian and Latin reception

[edit]Already in the thirteenth century, there were interval descriptions in Latin and Arabic treatises which proved that the use of the chromatic phthora was common not only among Greek singers.

Quţb al-Dīn al-Shīrīz distinguished two ways of using the chromatic genus in parde hiğāzī, named after a region of the Arabian Peninsula.[12] The exact proportions were used during changes to the diatonic genus. In both diatonic and chromatic divisions, the ring finger fret of the oud keyboard was used. It had the proportion 22:21—between middle and ring finger fret—and was called after the Baghdadi oud player Zalzal. These are the proportions, presented as a division of a tetrachord using the proportions of 22:21 and 7:6:

12:11 x 7:6 x 22:21 = 4:3 (approximate intervals in cents: 151, 267, 80 = 498)

This Persian treatise is the earliest source which tried to measure the exact proportions of a chromatic mode, which can be compared with historical descriptions of phthora nenano.

In his voluminous music treatise Jerome of Moravia described that "Gallian cantores" used to mix the diatonic genus with chromatic and the enharmonic, despite the use of the two latter were excluded according to Latin theorists:[13]

—Jerome of Moravia Tractatus de musica[14]

During the 1270s Jerome met the famous singers in Paris who were well skilled in the artistic performance of ars organi, which is evident by the chant manuscripts of the Abbey Saint-Maur-des-Fossés, of the Abbey Saint-Denis, and of the Notre Dame school. Despite the fact that no other Latin treatise ever mentioned that the singers were allowed to use enharmonic or chromatic intervals, and certainly not the transposition practice which was used sometimes by Greek singers, they obviously felt free enough to use both during the improvisation of organum—and probably, they became so familiar with the described enharmonic chromaticism, that they even used it during the monophonic performance of plainchant. Jerome as an educated listener regarded it as a "confusion" between monophonic and polyphonic performance style. Whatever his opinion about the performance style of Parisian cantores, the detailed description fit well to the use of the phthora nenano as an echos kratema, as it was mentioned in the later Greek treatises after the end of the Byzantine Empire.

The phthora nenano as kyrios echos and echos kratema

[edit]According to a Papadikē treatise in a sixteenth-century manuscript (Athens, National Library, Ms. 899 [EBE 899], fol.3f), the anonymous author even argues that phthorai nenano and nana are rather independent modes than phthorai, because singers as well as composers can create whole kratemata out of them:

—Anonymous comment in a Papadikē[15]

Kratemata were longer sections sung with abstract syllables in a faster tempo. As a disgression used within other forms in papadic or kalophonic chant genres—soloistic like cherubim chant or a sticheron kalophonikon. From a composer's point of view who composed within the mele of the octoechos, a kratema could not only recapitulate the modal structure of its model, but also create a change into another (chromatic or enharmonic) genus. If a composer or protopsaltes realised a traditional model of a cherubikon or koinonikon within the melos of echos protos, the phthora nenano will always end the form of the kratema in echos plagios devteros, only then the singer could find a way back to the main echos. In the later case the kratema was composed so perfectly in the proper melos of phthora nenano, that it could be performed as a separate composition of its own, as they were already separated compositions in the simpler genres like the troparion and the heirmologic odes of the canon since the 9th century.[16]

Gabriel Hieromonachus (mid fifteenth century) already mentioned that the "nenano phone"—the characteristic step (interval) of nenano—seemed to be in some way halved. On folio 5 verso of the quoted treatise (EBE 899), the author gave a similar description of the intervals used with the intonation formula νε–να–νὼ, and it fitted very well to the description that Jerome gave 300 years ago while he was listening to Parisian singers:

Ἄκουσον γὰρ τὴν φθορὰν, ὅπως λέγεται: Τότε λέγεται φθορὰ, ὅταν τῆς φωνῆς τὸ ἥμιου εἴπης ἐν ταῖς κατιούσαις, (ἢ κατ’ ἀκριφολογίαν τὸ τρίτον, ἐν δὲ ταῖς ἀνιούσαις) μίαν καὶ ἥμισυ, ὥσπερ εἰς τὸ νενανώ. Ἄκουσον γὰρ:

νε [ἴσον]—να [δικεντήματα]—να [ὀλίγον]—νω [ὀλίγον με τῇ διπλῇ]

Αὕτη ἡ φθορὰ εἰς τὰς ἀνιούσας. Ἰδοὺ γὰρ εἶπε τοῦ νω τὴν φωνὴν τὴν ἥμισυ εἰς τὸ να.

νε [ison]—να [dikentimata: small tone]—να [oligon: one and a half of the great tone]—νὼ [oligon with diple: diesis or quarter tone]

This is the intonation of phthora which is ascending. Concerning the final phonic step [which was a third of tonus in a descending melos], half of it is now part of the [second] να step [φωνή] and the rest [interval is sung] on νω!

— Gabriel Hieromonachos[17]

The upper small tone leading to the final note of the protos, has a slightly different intonation with respect to the melodic movement, at least according to the practice among educated singers of the Ottoman Empire during the eighteenth century. But Gabriel Hieromonachos described already in the fifteenth century, that the singers tend to stray away from their original intonation while they were singing the melos of phthora nenano:

—Gabriel Hieromonachos

Actual usage and meaning

[edit]Later use of the enechema (initial intonation formula) of nenano as well as the phthora (alteration and transposition sign) of nenano in manuscripts makes it clear that it is associated with the main form of the second plagal mode as it survives in the current practice of Byzantine (Greek Orthodox) chant. Furthermore, the phthora sign of nenano has survived in the nineteenth-century neo-Byzantine notation system which is still used to switch between a diatonic and chromatic intonation of the tetrachord one fourth below.

Chrysanthos' exegesis of the phthora nenano

[edit]In the chapter "About apechemata" (gr. τὸ ἀπήχημα was simply an alternative term to enechema, τὸ ἐνήχημα), Chrysanthos quoted the medieval apechema of the phthora nenano as a chromatic tetrachord between the pitch (phthongos) of plagios devteros and protos:

This intonation formulas avoids the enharmonic step (diesis) which is expected between tetartos (δ') and protos (α').

His exegesis of this short apechema sets the chromatic or enharmonic tetrachord between plagios protos (πλ α') and tetartos (δ'), so that the diesis lies between tritos (γ') and tetartos (δ'):

The common modern enechema places the tetrachord likewise:

Chrysanthos' exegeseis of the devteros echoi

[edit]The hard chromatic plagios devteros

[edit]

Chrysanthos of Madytos offered following exegesis of the traditional echema νεανες which was originally diatonic, but it is currently sung with the chromatic nenano intonation (see νεχὲ ανὲς in Chrysanthos' parallage):

Chrysanthos' exegesis employed the concluding cadence formula of the chromatic plagios devteros which was obviously an exegesis based on psaltic rules, as Manuel Chrysaphes had once mentioned them.

He described the correct intonation as follows:

—Chrysanthos of Madytos Theoretikon mega (§245)[20]

Despite this tradition, modern music teachers tried to translate this sophisticated intonation on a modern piano keyboard as "a kind of gipsy-minor."[21]

The soft chromatic kyrios devteros

[edit]In a very similar way—like the classical phthora nenano intonation—also the soft chromatic intonation of the echos devteros is represented as a kind of mesos devteros. Here according to Chrysanthos of Madytos the exegesis of the traditional devteros intonation can be sung like this:

He explained that the intonation of the modern echos devteros was not based on tetraphonia, but on trichords or diphonia:

§. 244. Ἡ χρωματικὴ κλίμαξ νη [πα ὕφεσις] βου γα δι [κε ὕφεσις] ζω Νη σχηματίζει ὄχι τετράχορδα, ἀλλὰ τρίχορδα πάντῃ ὅμοια καὶ συνημμένα τοῦτον τὸν τρόπον·

νη [πα ὕφεσις] βου, βου γα δι, δι [κε ὕφεσις] ζω, ζω νη Πα.

Αὕτη ἡ κλίμαξ ἀρχομένη ἀπὸ τοῦ δι, εἰμὲν πρόεισιν ἐπὶ τὸ βαρὺ, θέλει τὸ μὲν δι γα διάστημα τόνον μείζονα· τὸ δὲ γα βου τόνον ἐλάχιστον· τὸ δὲ βου πα, τόνον μείζονα· καὶ τὸ πα νη, τόνον ἐλάχιστον. Εἰδὲ πρόεισιν ἐπὶ τὸ ὀξὺ, θέλει τὸ μὲν δι κε διάστημα τόνον ἐλάχιστον· τὸ δὲ κε ζω, τόνον μείζονα· τὸ δὲ ζω νη, τόνον ἐλάχιστον· καὶ τὸ νη Πα, τόνον μείζονα. Ὥστε ταύτης τῆς χρωματικῆς κλίμακος μόνον οἱ βου γα δι φθόγγοι ταὐτίζονται μὲ τοὺς βου γα δι φθόγγους τῆς διατονικῆς κλίμακος· οἱ δὲ λοιποὶ κινοῦνται. Διότι τὸ βου νη διάστημα κατὰ ταύτην μὲν τὴν κλίμακα περιέχει τόνους μείζονα καὶ ἐλάχιστον· κατὰ δὲ τὴν διατονικὴν κλίμακα περιέχει τόνους ἐλάσσονα καὶ μείζονα· ὁμοίως καὶ τὸ δι ζω διάστημα

C νη—[D flat]—E βου, E βου—F γα—G δι, G δι—[a flat]—b ζω', b ζω'—c νη'—d πα'

If the scale starts on G δι, and it moves towards the lower, the step G δι—F γα requests the interval of a great tone (μείζων τόνος) and the step F γα—E βου a small tone (ἐλάχιστος τόνος); likewise the step E βου—[D flat] πα [ὕφεσις] an interval of μείζων τόνος, and the step πα [ὕφεσις] [D flat]—C νη one of ἐλάχιστος τόνος. When the direction is towards the higher, the step G δι—[a flat] κε [ὕφεσις] requests the interval of a small tone and [a flat] κε [ὕφεσις]—b ζω' that of a great tone; likewise the step b ζω'—c νη' an interval of ἐλάχιστος τόνος, and the step c νη'—Cd πα one of μείζων τόνος. Among the phthongoi of this chromatic scale only the phthongoi βου, γα, and δι can be identified with the same phthongoi of the diatonic scale, while the others are moveable degrees of the mode. While this scale extends between E βου and C νη over one great and one small tone [12+7=19], the diatonic scale extends from the middle (ἐλάσσων τόνος) to the great tone (μείζων τόνος) [12+9=21], for the interval between G δι and b ζω' it is the same.

—Chrysanthos Theoretikon mega (§244)[22]

Phthora nenano as an "Ottoman corruption"

[edit]Because of its early status as one of the two mysterious extra modes in the system, nenano has been subject of much attention in Byzantine and post-Byzantine music theory. Papadikai like the manuscript EBE 899 and other late Byzantine manuscripts associate nenano and nana with the chromatic and the enharmonic genus, one of the three genera of tuning during Classical antiquity that fell into early misuse because of its complexity. If the phthora nenano was already chromatic during the 9th century, including the use of one enharmonic diesis, is still a controversial issue, but medieval Arabic, Persian and Latin authors like Jerome of Moravia rather hint to the possibility that it was.

Greek music theoreticians such as Simon Karas continue up to the end of the twentieth century to regard the intonation nenano as "exotic," although they do not always agree, whether the echos plagios devteros intonation is hard or soft chromatic.[23] Anonymous authors like the one of the 16th-century Papadike (EBE 899) maintained, that one of the minor tones in the tetrachord of nenano should be either smaller or larger than a tempered semitone, approaching the smallest interval of a third or a quarter of a tone. The banishment of instrumental musical practice and its theory from the tradition of Byzantine chant has made it very difficult to substantiate any such claims experimentally, and traditional singers use different intonations depending on their school. The only possible conclusions can be drawn indirectly and tentatively through comparisons with the tradition of Ottoman instrumental court music, which important church theoreticians such as the Kyrillos Marmarinos, Archbishop of Tinos considered a necessary complement to liturgical chant.[24] However, Ottoman court music and its theory are also complex and diverging versions of modes exist according to different schools, ethnic traditions or theorists. There, one encounters various versions of the "nenano" tetrachord, both with a narrow and with a wider minor second either at the top or at the bottom, depending on the interval structure of the scale beyond the two ends of the tetrachord.

Although the phthora nenano is already known as one of two additional phthorai used within the Hagiopolitan octoechos, its chromaticism was often misunderstood as a late corruption of Byzantine chant during the Ottoman Empire, but recent comparisons with medieval Arabic treatises proved that this exchange can dated back to a much earlier period, when Arab music was created as a synthesis of Persian music and Byzantine chant of Damascus.[25]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Peter Jeffery (2001) compared the Greek and the Latin octoechos and found, that a modal classification of Gregorian chant according to the octoechos was analytically deduced a posteriori.

- ^ See Barbera's entry "Metabolē".

- ^ Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, fonds grec, ms. 360.

- ^ Peter Jeffery (2001), Christian Hannick & Gerda Wolfram (1997).

- ^ John of Damascus and Cosmas entered the Lavra Agios Sabas about 700, after the reform was already established by a synodal decree in 692, and certain passages paraphrases polemics against the 16 echoi of the Constantinopolitan cathedral rite (Raasted 1983, 16—§8, Jeffery 2001, 186f).

- ^ Hagiopolites (Raasted 1983, pp. 10-11).

- ^ In the same way it was used by authors of Arabic treatises who referred to composers who avoided and others who liked the use of certain exotic tunes, while ancient Greek theorists did refer to older methods of composition.

- ^ Quoted according to Jørgen Raasted (1983, pp. 42f) with a slightly modified translation.

- ^ See Barbera's entry "Metabolē" (New Grove Dictionary).

- ^ Eustathios Makris (2005).

- ^ Dimitri Conomos (1985, p. 64).

- ^ Iannis Zannos (1994, 105f).

- ^ Oliver Gerlach (2010, 130) in his discussion of the earliest sources for the practice of phthora nenano pointed out, that Jerome who had an exceptional knowledge of Greek music theory, described the use of chromaticism among Parisian singers as a kind of phthora nenano.

- ^ Simon Cserba (1935, ii:187).

- ^ Quotation according to Iannis Zannos (1994, 110f).

- ^ Listen to Chourmouzios' transcription of John Koukouzeles' kratema.

- ^ Citation according to Zannos (1994, 112). The folio 5 verso of the manuscript was reproduced by Eustathios Makris in his article (2005, 4—fig.1). Thus, he proved that the little addition about the descending intonation cannot be found as quoted by Ioannis Zannos (probably this was the eighteenth-century redaction in Cod. Athos, Xeropotamou 317), therefore it is written here in rectangular brackets. In fact the standard intonation given in EBE 899 is just ascending.

- ^ Christian Hannick & Gerda Wolfram (1985, 98—lines 680-86).

- ^ English translation by Eustathios Makris (2005, 3f).

- ^ Chrysanthos (1832, 106).

- ^ According to this simplification a phthora of nenano is placed on δι, which in Western terms corresponds to the tone "G" (sol), then it indicates a chromatic tetrachord, approximated by the notes: D-high E flat-high F sharp-G. This is similar to the upper part of a G minor harmonic scale, or of the "Zigeunermoll" (gipsy-minor) scale. In other words, nenano is the prototype of the scale structure that includes an augmented second—which Hieronymus and Chrysanthos call more precise "trihemitone"—between two minor seconds and that is nowadays one of the most well known clichés commonly associated with near eastern or middle eastern "oriental" musical color.

- ^ Chrysanthos (1832, 105-106).

- ^ Among Phanariotes Simon Karas (1981) has another explanation as Chrysanthos' trichordal concept of echos devteros which tried to integrate psaltic tradition to base the phthora on the phthongos plagios devteros (πλ β'). These different approaches make a historical explanation very difficult (Makris 2005).

- ^ Eugenia Popescu-Județ and Adriana Şırlı (2000).

- ^ Eckhard Neubauer (1998).

References

[edit]Sources

[edit]- "Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, fonds grec, Ms. 360, ff.216r-237v". Βιβλίον ἁγιοπολίτης συγκροτημένον ἔκ τινων μουσικῶν μεθόδων [The book of the Holy Polis "Jerusalem" unifying different musical methods] in a compiled collection of basic grammar treatises and fragments with mathemataria and of a menologion (12th century).

- Panagiotes the New Chrysaphes. "London, British Library, Harley Ms. 5544, fol. 3r-8v". Papadike and the Anastasimatarion of Chrysaphes the New, and an incomplete Anthology for the Divine Liturgies (17th century). British Library. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

Editions of Music Theory Treatises

[edit]- Raasted, Jørgen, ed. (1983). The Hagiopolites: A Byzantine Treatise on Musical Theory (PDF). Cahiers de l'Institut du Moyen-Âge Grec et Latin. Vol. 45. Copenhagen: Paludan.

- Hannick, Christian; Wolfram, Gerda, eds. (1997). Die Erotapokriseis des Pseudo-Johannes Damaskenos zum Kirchengesang. Monumenta Musicae Byzantinae - Corpus Scriptorum de Re Musica. Vol. 5. Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. ISBN 3-7001-2520-8.

- Cserba, Simon M., ed. (1935). Hieronymus De Moravia O.P.: Tractatus De Musica. Regensburg: F. Pustet.

- Conomos, Dimitri, ed. (1985). The Treatise of Manuel Chrysaphes, the Lampadarios: [Περὶ τῶν ἐνθεωρουμένων τῇ ψαλτικῇ τέχνῃ καὶ ὧν φρουνοῦσι κακῶς τινες περὶ αὐτῶν] On the Theory of the Art of Chanting and on Certain Erroneous Views that some hold about it (Mount Athos, Iviron Monastery MS 1120, July 1458). Monumenta Musicae Byzantinae - Corpus Scriptorum de Re Musica. Vol. 2. Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. ISBN 978-3-7001-0732-3.

- Hannick, Christian; Wolfram, Gerda, eds. (1985). Gabriel Hieromonachus: [Περὶ τῶν ἐν τῇ ψαλτικῇ σημαδίων καὶ τῆς τούτων ἐτυμολογίας] Abhandlung über den Kirchengesang. Monumenta Musicae Byzantinae - Corpus Scriptorum de Re Musica. Vol. 1. Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. ISBN 3-7001-0729-3.

- Popescu-Județ, Eugenia; Şırlı, Adriana Arabi, eds. (2000). Sources of 18th Century Music: Panayiotes Chalatzoglou and Kyrillos Marmarinos' Comparative Treatises on Secular Music. Pan Yayıncılık. Istanbul: Pan. ISBN 975-8434-05-5.

- Chrysanthos of Madytos (1832). Pelopides, Panagiotes G. (ed.). Θεωρητικόν μέγα της μουσικής συνταχθέν μεν παρά Χρυσάνθου αρχιεπισκόπου Διρραχίου του εκ Μαδύτων εκδοθέν δε υπό Παναγιώτου Γ. Πελοπίδου Πελοποννησίου διά φιλοτίμου συνδρομής των ομογενών. Triest: Michele Weis. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- Karas, Simon (1981). Μέθοδoς τῆς Ἐλληνικῆς Μουσικῆς: Θεωρητικόν. Athens: Association for the Dissemination of National Music.

Studies

[edit]- Amargianakis, George (1977). "An Analysis of Stichera in the Deuteros Modes: The Stichera idiomela for the Month of September in the Modes Deuteros, Plagal Deuteros, and Nenano; transcribed from the Manuscript Sinai 1230 <A.D. 1365>" (PDF). Cahiers de l'Institut du Moyen-Âge Grec et Latin. 22–23: 1–269.

- Barbera, André. "Metabolē". Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- Neubauer, Eckhard (1998), "Die acht "Wege" der arabischen Musiklehre und der Oktoechos – Ibn Misğah, al-Kindī und der syrisch-byzantinische oktōēchos", Arabische Musiktheorie von den Anfängen bis zum 6./12. Jahrhundert: Studien, Übersetzungen und Texte in Faksimile, Publications of the Institute for the History of Arabic-Islamic Science: The science of music in Islam, vol. 3, Frankfurt am Main: Inst. for the History of Arab.-Islamic Science, pp. 373–414.

- Gerlach, Oliver (2010). "Phthora und Tongeschlecht – φθορά καί γένος". Im Labyrinth des Oktōīchos — Über die Rekonstruktion einer mittelalterlichen Improvisationspraxis in der Musik der Ost- & Westkirche (doctoral thesis). Berlin: Ison. pp. 125–134. ISBN 978-3-00-032306-5. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- Jeffery, Peter (2001). "The Earliest Oktōēchoi: The Role of Jerusalem and Palestine in the Beginnings of Modal Ordering". The Study of Medieval Chant: Paths and Bridges, East and West; In Honor of Kenneth Levy. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell Press. pp. 147–209. ISBN 0-85115-800-5.

- Makris, Eustathios (2005). "The Chromatic Scales of the Deuteros Modes in Theory and Practice". Plainsong and Medieval Music. 14: 1–10. doi:10.1017/S0961137104000075. ISSN 0961-1371. S2CID 162385479.

- Zannos, Ioannis (1994). Ichos und Makam - Vergleichende Untersuchungen zum Tonsystem der griechisch-orthodoxen Kirchenmusik und der türkischen Kunstmusik. Orpheus-Schriftenreihe zu Grundfragen der Musik. Bonn: Verlag für systematische Musikwissenschaft. ISBN 978-3-922626-74-9.

External links

[edit]- Koukouzeles, John. "Kratema composed in phthora nenano". Greek-Byzantine Choir. Archived from the original on 2021-12-21.