Thousand Character Classic

| Thousand Character Classic | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

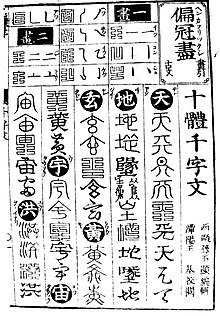

A calligraphic work titled An Authentic "Thousand Character Classic", Song dynasty | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 千字文 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Qiānzì wén | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | Thiên tự văn | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chữ Hán | 千字文 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 천자문 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 千字文 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 千字文 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

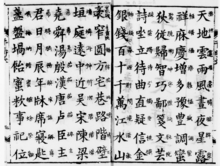

The Thousand Character Classic (Chinese: 千字文; pinyin: Qiānzì wén), also known as the Thousand Character Text, is a Chinese poem that has been used as a primer for teaching Chinese characters to children from the sixth century onward. It contains exactly one thousand characters, each used only once, arranged into 250 lines of four characters apiece and grouped into four line rhyming stanzas to facilitate easy memorization. It is sung, akin to alphabet songs for phonetic writing systems. Along with the Three Character Classic and the Hundred Family Surnames, it formed the basis of traditional literacy training in the Sinosphere.

The first line is Tian di xuan huang (traditional Chinese: 天地玄黃; simplified Chinese: 天地玄黄; pinyin: Tiāndì xuán huáng; Jyutping: Tin1 dei6 jyun4 wong4; lit. 'Heaven earth dark yellow') and the last line, Yan zai hu ye (焉哉乎也; Yān zāi hū yě; Yin1 zoi1 fu4 jaa5) explains the use of the grammatical particles yan, zai, hu, and ye.[1]

History

[edit]There are several stories of the work's origin. One says that Emperor Wu of the Liang dynasty (r. 502–549) commissioned Zhou Xingsi (traditional Chinese: 周興嗣; simplified Chinese: 周兴嗣; pinyin: Zhōu Xìngsì, 470–521) to compose this poem for his prince to practice calligraphy. Another says that the emperor commanded Wang Xizhi, a noted calligrapher, to write out one thousand characters and give them to Zhou as a challenge to make into an ode. Another story is that the emperor commanded his princes and court officers to compose essays and ordered another minister to copy them on a thousand slips of paper, which became mixed and scrambled. Zhou was given the task of restoring these slips to their original order. He worked so intensely to finish doing so overnight that his hair turned completely white.[2]

The Thousand Character Classic is understood to be one of the most widely read texts in China in the first millennium.[3] The popularity of the book in the Tang dynasty is shown by the fact that there were some 32 copies found in the Dunhuang archaeological excavations. By the Song dynasty, since all literate people could be assumed to have memorized the text, the order of its characters was used to put documents in sequence in the same way that alphabetical order is used in alphabetic languages.[4]

The Buddhist Uyghur Kingdom of Qocho used the thousand character classic and the Qieyun and it was written that "In Qocho city were more than fifty monasteries, all titles of which are granted by the emperors of the Tang dynasty, which keep many Buddhist texts as Tripitaka, Tangyun, Yupuan, Jingyin etc."[5]

In the dynasties following the Song, the Three Character Classic, Hundred Family Surnames, and 1,000 Character Classic came to be known collectively as San Bai Qian (Three, Hundred, Thousand), from the first character in their titles. They were the almost universal introductory literacy texts for students, almost exclusively boys, from elite backgrounds and even for a number of ordinary villagers. Each was available in many versions, printed cheaply, and available to all since they did not become superseded. When a student had memorized all three, he could recognize and pronounce, though not necessarily write or understand the meaning of, roughly 2,000 characters (there was some duplication among the texts). Since Chinese did not use an alphabet, this was an effective, albeit time-consuming, way of giving a "crash course" in character recognition before going on to understanding texts and writing characters.[6]

During the Song dynasty, the noted neo-Confucianism scholar Zhu Xi, inspired by the three classics, wrote Xiaoxue or Elementary Learning[citation needed].

Calligraphy

[edit]Due to the fact that the Thousand Character Classic contains a thousand unique Chinese characters, and its wide circulation, it has been highly favored by calligraphers in East Asian countries. According to the Xuanhe Calligraphy Catalogue (宣和画谱), the Northern Song imperial collection included twenty-three authentic works by Sui dynasty calligrapher Zhiyong (a descendant of Wang Xizhi), fifteen of which were copies of the Thousand Character Classic.

Chinese calligraphers such as Chu Suiliang, Sun Guoting, Zhang Xu, Huaisu, Mi Yuanzhang (Northern Song), Emperor Gaozong of Southern Song, Emperor Huizong of Song, Zhao Mengfu, and Wen Zhengming all have notable calligraphic works of the Thousand Character Classic. Manuscripts unearthed from Dunhuang also contain practice fragments of the Thousand Character Classic, indicating that by the 7th century at the latest, using the Thousand Character Classic to practice Chinese calligraphy had become quite widespread.

Japan

[edit]Wani, a semi-legendary Chinese-Baekje scholar,[7] is said to have translated the Thousand Character Classic to Japanese along with 10 books of the Analects of Confucius during the reign of Emperor Ōjin (r. 370?-410?). However, this alleged event precedes the composition of the Thousand Character Classic. This makes many assume that the event is simply fiction, but some[who?] believe it to be based in fact, perhaps using a different version of the Thousand Character Classic.

Korea

[edit]The Thousand Character Classic has been used as a primer for learning Chinese characters for many centuries. It is uncertain when the Thousand Character Classic was introduced to Korea.

The book is noted as a principal force—along with the introduction of Buddhism into Korea—behind the introduction of Chinese characters into the Korean language. Hanja was the sole means of writing Korean until the Hangul script was created under the direction of King Sejong the Great in the 15th century; however, even after the invention of Hangul, most Korean scholars continued to write in Hanja until the late 19th century.

The Thousand Character Classic's use as a writing primer for children began in 1583, when King Seonjo ordered Han Ho (1544–1605) to carve the text into wooden printing blocks.

The Thousand Character Classic has its own form in representing the Chinese characters. For each character, the text shows its meaning (Korean Hanja: 訓; saegim or hun) and sound (Korean Hanja: 音; eum). The vocabulary to represent the saegim has remained unchanged in every edition, despite the natural evolution of the Korean language since then. However, in the editions Gwangju Thousand Character Classic and Seokbong Thousand Character Classic, both written in the 16th century, there are a number of different meanings expressed for the same character. The types of changes of saegims in Seokbong Thousand Character Classic into those in Gwangju Thousand Character Classic fall roughly under the following categories:

- Definitions turned more generalized or more concrete when semantic scope of each character had been changed

- Former definitions were replaced by synonyms

- Parts of speech in the definitions were changed

From these changes, replacements between native Korean and Sino-Korean can be found. Generally, "rare saegim vocabularies" are presumed to be pre-16th century, for it is thought that they may be a fossilized form of native Korean vocabulary or affected by the influence of a regional dialect in Jeolla Province.

South Korean senior scholar, Daesan Kim Seok-jin (Korean Hangul: 대산 김석진), expressed the significance of Thousand Character Classic by contrasting the Western concrete science and the Asian metaphysics and origin-oriented thinking in which "it is the collected poems of nature of cosmos and reasons behind human life".[8]

The first 44 characters of the Thousand Character Classic were used on the reverse sides of some Sangpyeong Tongbo cash coins of the Korean mun currency to indicate furnace or "series" numbers.[9]

Vietnam

[edit]

There is a version of Thousand Character Classic that was changed to the Vietnamese lục bát (chữ Hán: 六八) verse form. The text itself is called Thiên tự văn giải âm (chữ Hán: 千字文解音), and it was published in 1890 by Quan Văn Đường (chữ Hán: 觀文堂). The text is annotated with chữ Nôm characters, for example, the character 地 is annotated with its chữ Nôm equivalent 坦. Because it was changed to the lục bát verse form, many characters are changed such as in the first line,[10]

| Original text | Vietnamese transliteration | Vietnamese text | Vietnamese alphabet |

|---|---|---|---|

| 天地玄黃 | Thiên địa huyền hoàng | 天𡗶地坦雲𩄲 | Thiên trời địa đất vân mây |

| 宇宙洪荒 | Vũ trụ hồng hoang | 雨湄風𩙌晝𣈜夜𣈘 | Vũ mưa phong gió trú ngày dạ đêm |

Manchu texts

[edit]Several different Manchu texts of the Thousand Character Classic are known today. They all use the Manchu script to transcribe Chinese characters. They are utilized in research on Chinese phonology.

The Man han ciyan dzi wen (simplified Chinese: 满汉千字文; traditional Chinese: 滿漢千字文; pinyin: Mǎn hàn qiān zì wén; Jyutping: mun5 hon3 cin1 zi6 man4) written by Chen Qiliang (simplified Chinese: 沉启亮; traditional Chinese: 沈啓亮; pinyin: Chénqǐliàng; Jyutping: cam4 kai2 loeng6), contains Chinese text and Manchu phonetic transcription. This version was published during the reign of the Kangxi Emperor.[11]

Another text, the Qing Shu Qian Zi Wen (simplified Chinese: 清书千字文; traditional Chinese: 清書千字文; pinyin: Qīngshū qiān zì wén; Jyutping: cing1 syu1 cin1 zi6 man4) by You Zhen (Chinese: 尤珍; pinyin: Yóu Zhēn; Jyutping: jau4 zan1), was published in 1685 as a supplement to the Baiti Qing Wen (simplified Chinese: 百体清文; traditional Chinese: 百體清文; pinyin: Bǎi tǐ qīngwén; Jyutping: baak3 tai2 cing1 man4). It provides Manchu transcription without original Chinese. It is known for being referred to by Japanese scholar Ogyū Sorai for Manchu studies as early as the 18th century.[12]

The undated ciyan dzi wen which is owned by the Bibliothèque nationale de France is a variant of the Qing Shu Qian Zi Wen. It is believed to have been used by the translation office of the Joseon Dynasty of Korea. It contains Hangul transcription for both Manchu and Chinese.[13] It is valuable to the study of Manchu phonology.

Text variants

[edit]The text of the Qiānzì Wén is not available in an authoritative, standardized version. Comparison of various manuscript, printed and electronic editions shows that these do not all contain exactly the same 1,000 characters. In many cases the differences concern just small graphic variations (for example character no. 4, 黃 or 黄, both huáng "yellow"). In other cases variant characters are quite different, although still associated with the same pronunciation and meaning (for example character no. 123, 一 or 壹, both yì "one"). In a few cases, variant characters represent different pronunciations and meanings (for example character no. 132, 竹 zhú "bamboo" or 樹 shù "tree"). These textual variants are not noted or discussed in any existing edition of the text in a western language. In fact, even the text appended to this article differs from the text presented in Wikisource in 25 places (nos. 123 一/壹, 132 竹/樹, 428 郁/鬱, 438 彩/綵, 479 群/羣, 482 稿/稾, 554 回/迴, 617 岳/嶽, 619 泰/恆, 643 綿/緜, 645 岩/巖/, 693 鑒/鑑, 733 沉/沈/, 767 蚤/早, 776 搖/颻, 787 玩/翫, 803 餐/飡, 846 筍/笋, 849 弦/絃, 852 宴/讌, 854 杯/盃, 881 箋/牋, 953 璿/璇, 980 庄/莊). A critical text edition of the Qiānzì Wén, based upon the best manuscript and printed sources, has not yet been attempted.

Text

[edit]| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 天地玄黃,宇宙洪荒。 | 龍師火帝,鳥官人皇。 | 蓋此身髮,四大五常。 | 都邑華夏,東西二京。 | 治本於農,務茲稼穡。 | 耽讀玩市,寓目囊箱。 | 布射僚丸,嵇琴阮嘯。 |

| 日月盈昃,辰宿列張。 | 始制文字,乃服衣裳。 | 恭惟鞠養,豈敢毀傷。 | 背邙面洛,浮渭據涇。 | 俶載南畝,我藝黍稷。 | 易輶攸畏,屬耳垣牆。 | 恬筆倫紙,鈞巧任釣。 |

| 寒來暑往,秋收冬藏。 | 推位讓國,有虞陶唐。 | 女慕貞絜,男效才良。 | 宮殿盤郁,樓觀飛驚。 | 稅熟貢新,勸賞黜陟。 | 具膳餐飯,適口充腸。 | 釋紛利俗,竝皆佳妙。 |

| 閏餘成歲,律呂調陽。 | 弔民伐罪,周發殷湯。 | 知過必改,得能莫忘。 | 圖寫禽獸,畫彩仙靈。 | 孟軻敦素,史魚秉直。 | 飽飫烹宰,飢厭糟糠。 | 毛施淑姿,工顰妍笑。 |

| 雲騰致雨,露結為霜。 | 坐朝問道,垂拱平章。 | 罔談彼短,靡恃己長。 | 丙舍傍啟,甲帳對楹。 | 庶幾中庸,勞謙謹敕。 | 親戚故舊,老少異糧。 | 年矢每催,曦暉朗曜。 |

| 金生麗水,玉出崑岡。 | 愛育黎首,臣伏戎羌。 | 信使可覆,器欲難量。 | 肆筵設席,鼓瑟吹笙。 | 聆音察理,鑒貌辨色。 | 妾御績紡,待巾帷房。 | 璿璣懸斡,晦魄環照。 |

| 劍號巨闕,珠稱夜光。 | 遐邇一體,率賓歸王。 | 墨悲絲染,詩讚羔羊。 | 升階納陛,弁轉疑星。 | 貽厥嘉猷,勉其祗植。 | 紈扇圓潔,銀燭煒煌。 | 指薪修祜,永綏吉劭。 |

| 果珍李柰,菜重芥姜。 | 鳴鳳在竹,白駒食場。 | 景行維賢,克念作聖。 | 右通廣內,左達承明。 | 省躬譏誡,寵增抗極。 | 晝眠夕寐,藍筍象床。 | 矩步引領,俯仰廊廟。 |

| 海咸河淡,鱗潛羽翔。 | 化被草木,賴及萬方。 | 德建名立,形端表正。 | 既集墳典,亦聚群英。 | 殆辱近恥,林皋幸即。 | 弦歌酒宴,接杯舉觴。 | 束帶矜庄,徘徊瞻眺。 |

| 空谷傳聲,虛堂習聽。 | 杜稿鍾隸,漆書壁經。 | 兩疏見機,解組誰逼。 | 矯手頓足,悅豫且康。 | 孤陋寡聞,愚蒙等誚。 | ||

| 禍因惡積,福緣善慶。 | 府羅將相,路俠槐卿。 | 索居閒處,沉默寂寥。 | 嫡後嗣續,祭祀烝嘗。 | 謂語助者,焉哉乎也。 | ||

| 尺璧非寶,寸陰是競。 | 戶封八縣,家給千兵。 | 求古尋論,散慮逍遙。 | 稽顙再拜,悚懼恐惶。 | |||

| 資父事君,曰嚴與敬。 | 高冠陪輦,驅轂振纓。 | 欣奏累遣,慼謝歡招。 | 箋牒簡要,顧答審詳。 | |||

| 孝當竭力,忠則盡命。 | 世祿侈富,車駕肥輕。 | 渠荷的歷,園莽抽條。 | 骸垢想浴,執熱願涼。 | |||

| 臨深履薄,夙興溫凊。 | 策功茂實,勒碑刻銘。 | 枇杷晚翠,梧桐蚤凋。 | 驢騾犢特,駭躍超驤。 | |||

| 似蘭斯馨,如松之盛。 | 磻溪伊尹,佐時阿衡。 | 陳根委翳,落葉飄搖。 | 誅斬賊盜,捕獲叛亡。 | |||

| 川流不息,淵澄取映。 | 奄宅曲阜,微旦孰營。 | 游鵾獨運,凌摩絳霄。 | ||||

| 容止若思,言辭安定。 | 桓公匡合,濟弱扶傾。 | |||||

| 篤初誠美,慎終宜令。 | 綺回漢惠,說感武丁。 | |||||

| 榮業所基,藉甚無竟。 | 俊乂密勿,多士寔寧。 | |||||

| 學優登仕,攝職從政。 | 晉楚更霸,趙魏困橫。 | |||||

| 存以甘棠,去而益詠。 | 假途滅虢,踐土會盟。 | |||||

| 樂殊貴賤,禮別尊卑。 | 何遵約法,韓弊煩刑。 | |||||

| 上和下睦,夫唱婦隨。 | 起翦頗牧,用軍最精。 | |||||

| 外受傅訓,入奉母儀。 | 宣威沙漠,馳譽丹青。 | |||||

| 諸姑伯叔,猶子比兒。 | 九州禹跡,百郡秦并。 | |||||

| 孔懷兄弟,同氣連根。 | 岳宗泰岱,禪主云亭。 | |||||

| 交友投分,切磨箴規。 | 雁門紫塞,雞田赤城。 | |||||

| 仁慈隱惻,造次弗離。 | 昆池碣石,鉅野洞庭。 | |||||

| 節義廉退,顛沛匪虧。 | 曠遠綿邈,岩岫杳冥。 | |||||

| 性靜情逸,心動神疲。 | ||||||

| 守真志滿,逐物意移。 | ||||||

| 堅持雅操,好爵自縻。 |

See also

[edit]- Chengyu (traditional Chinese four-character parables)

- Pakapoo (the use of the Thousand Character Classic as a lottery)

Similar poems in other languages

[edit]- Alphabet song

- Hanacaraka, Javanese

- Iroha, Japanese

- Tam thiên tự, Vietnamese

- Shiva Sutra, Sanskrit

References

[edit]- ^ Paar (1963), p. 7, 36.

- ^ Paar (1963), p. 3.

- ^ Idema, Wilt L. (2017). "Chapter 17: Elite versus Popular Literature". In Denecke, Wiebke; Li, Wai-yee; Tian, Xiaofei (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Classical Chinese Literature (1000 BCE-900 CE). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 234. ISBN 9780199356591.

- ^ Wilkinson, Endymion (2012). Chinese History: A New Manual. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center. ISBN 9780674067158., pp. 295, 601

- ^ Abdurishid Yakup (2005). The Turfan Dialect of Uyghur. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 180–. ISBN 978-3-447-05233-7.

- ^ Rawski (1979), pp. 46–48.

- ^ Encyclopedia Nipponica "王仁は高句麗(こうくり)に滅ぼされた楽浪(らくろう)郡の漢人系統の学者らしく、朝廷の文筆に従事した西文首(かわちのふみのおびと)の祖とされている。"

- ^ Lee (이), In-u (인우); Kang Jae-hun (강재훈) (2012-01-03). [이사람] "천자문이 한문 입문서? 우주 이치 담은 책". The Hankyoreh (in Korean). Retrieved 2012-01-03.

- ^ "Korean Coins – 韓國錢幣 - History of Korean Coinage". Gary Ashkenazy / גארי אשכנזי (Primaltrek – a journey through Chinese culture). 16 November 2016. Retrieved 5 June 2017.

- ^ "Thiên tự văn giải âm. 千字文解音". Bibliothèque nationale de France. 1890.

- ^ Ikegami Jirō (池上二郎): Manchu Materials in European Libraries (Yōroppa ni aru Manshūgo bunken ni tsuite; ヨーロッパにある満洲語文献について), Researches on the Manchu Language (満洲語研究; Manshūgo Kenkyū), pp.361–363, Publish date: 1999.

- ^ Kanda Nobuo 神田信夫: Ogyū Sorai no "Manbunkō" to "Shinsho Senjimon" 荻生徂徠の『満文考』と「清書千字文」 (On Ogyū Sorai's "Studies of Written Manchu" and "The Manchu Thousand-Character Classic"), Shinchōshi Ronkō 清朝史論考 (Studies on Qing-Manchu History: Selected Articles), pp. 418-431頁, 2005.

- ^ Kishida Fumitaka 岸田文隆: On Ciyan dzi wen/Ch'ien-tzu-wen (千字文) in Bibliothèque Nationale (I) (パリ国民図書館所蔵の満漢「千字文」について (I); Pari Kokumin Toshokan shozō no Mankan "Senjimon" ni tsuite (I)), Journal of the Faculty of Humanities Toyama University (富山大学人文学部紀要; Toyama Daigaku Jinbungakubu Kiyō) No.21, pp.77-133, 1994.

- ^ Sturman, Nathan. "The Thousand Character Essay, Qiānzì Wén, in Mandarin Chinese, (read as Senjimon in Japanese, Chonjyamun in Korean) (Archived)". Archived from the original on 2019-04-03. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

Bibliography

[edit]- Paar, Francis W., ed. (1963). Chʻien Tzu Wen the Thousand Character Classic; a Chinese Primer. New York: Frederic Ungar. Online at Hathi Trust. Includes text (in four scripts), extensive notes, and translations into four languages.

- Rawski, Evelyn Sakakida (1979). Education and Popular Literacy in Ch'ing China. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472087533.

External links

[edit]- Transcribed, Translated and Annotated Thousand Character Essay by Nathan Sturman

- Cambridge Chinese Classics: Qianziwen

- Thousand-Character Essay [Qianzi Wen] [1]

- 周興嗣 (1858). 千字文釋句. 皇家義學. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- 補拙居士; 姜岳 (1895). 增註三千字文. 梅江廬主人. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- 周(Zhou), 興嗣(Xingsi). 千字文. Archived from the original on 3 July 2012. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- 千字文全文诵读 (Reading of the Complete Thousand Character Classic, archived from the original on 2021-12-21

Qian Zi Wen public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Qian Zi Wen public domain audiobook at LibriVox- Thousand Character Classic 千字文 Chinese text with embedded Chinese-English reader dictionary at Chinese Notes