Ḫartapus

| Ḫartapus | |

|---|---|

| |

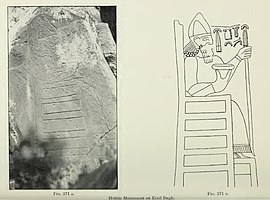

The Kızıldağ relief of Ḫartapus with his aedicula in front of him. | |

| Great king of ? | |

| Reign | Early 8th century BCE |

| Predecessor | Mursilis (?) |

| Luwian | 𔓟𔖱𔐞𔕯𔗔[1][2] |

| Father | Mursilis |

Ḫartapus or Kartapus was an Anatolian king who in the early 8th century BCE ruled a state in what is presently the region of Konya in modern Turkey.[3][4]

Name

[edit]The name of this king was variously written as:[5][6]

Etymology

[edit]The name Ḫartapus/Kartapus is not attested outside of this king's inscriptions and it does not correspond to Hittite or Luwian naming conventions,[9] and was thus a non-Luwian name.[10] It has therefore been interpreted as a Luwian pronunciation of a non-Luwian name.[11]

Alternative reading

[edit]An alternative reading of this king's name could be Ḫarputas or Ḫarbudas, which might be composed of the Anatolian suffix -tta-, and whose root might also be found in the toponyms Ḫarbudā (𒌷𒄯𒁍𒋫𒀀𒀸[12]) and Ḫarbudauna (𒌷𒄯𒁍𒋫𒌋𒈾𒀸[13]).[9]

Dating

[edit]The monuments of Ḫartapus show a discrepancy between their art style, which show Neo-Assyrian influence, and their palaeography, which reflects a style from the 13th century BCE. Additionally, Ḫartapus himself is not known outside of his own monuments and is not mentioned in Neo-Assyrian sources, which has led to significant debate regarding how to date Hartapus since the discovery of this king in the early 20th century AD.[14]

Early dating

[edit]Due to the archaising features of the inscriptions of Ḫartapus which show significant similarities with the Hieroglyphic Luwian writing traditions of the Hittite Empire, as well as the typically Hittite name of his father Mursilis, his reign had previously been dated to the late 2nd millennium BCE:[15][16]

- according to Trevor Bryce, Ḫartapus lived in the 13th century BCE during the final years of the Hittite Empire;[15]

- according to Mark Weeden, Ḫartapus lived in the early 12th century BCE, in the period immediately following the collapse of the Hittite Empire.[17]

According to proponents of an earlier dating of Ḫartapus, the designation Muska for a people defeated by him referred to a population with a specific lifestyle rather than to an ethnic group, and was identical with the Eastern Muški of the Assyrian records.[17]

Several proposals for the identity of Ḫartapus were proposed within the earlier dating scheme:

- Dietrich Sürenhagen had identified him as the son of the Hittite king Muršili II, thus making Ḫartapus a brother of Muwatalli II and Ḫattušili III.[18][19]

- the earlier identification prevalent among Hittitologists considered him to be the son of the Hittite king Urḫi-Teššub, who had assumed the throne name of Mursili III before being dethroned by Ḫattušili III, after which his descendants formed their own rival kingdom in Tarḫuntašša; according to this proposal, the Kızıldağ relief was instead carved at least four centuries after Ḫartapus, by either Wasusarmas of Tabal[20][21][22] or Ambaris of Bīt-Burutaš.[23][24]

- Bryce hypothesised that Ḫartapus had ruled from Tarḫuntašša and attempted to claim the Hittite throne following the ouster of his father, with his victories mentioned in his inscriptions referring to his wars against the authority in Ḫattusa, which were alluded to by the ruling Hittite king Tudḫaliya IV as rebellions that he had to deal with.[25][16]

- Rostyslav Oreshko dated the inscriptions of Ḫartapus to the 12th or early 11th century BCE[26] and identified him as a king of Maša[27] in northwestern Anatolia,[28] which he identified with Muska, that is early Phrygia.[29]

- Oreshko hypothesised that the inscriptions of Ḫartapus referred to an attempt by him to expand Masa up to the eastern and southeastern mountain boundaries of the Central Anatolian Plains after the collapse of the Hittite Empire.[30]

Double Ḫartapus hypothesis

[edit]According to Weeden and John David Hawkins, most of the inscriptions by Ḫartapus, especially the 4th Kızıldağ and 1st Karadağ inscriptions, had been written in the 12th century BCE, while the 1st Kızıldağ, Burunkaya, 1st Türkmen-Karahöyük, and his relief were from the 8th century BCE.[31] Their conclusion, which was also shared by Lorenzo D'Alfonso and Matteo Pedrinazzi, was therefore that two Ḫartapus had reigned:[32][33][31]

- a Ḫartapus I, son of Mursilis, who had reigned in the 12th century BCE, and who had defeated the Muska;

- and a Ḫartapus II, who was not the son of Mursilis and who reigned in the early 8th century BCE.

Proponents of this double king hypothesis have identify Ḫartapus I as a descendant of the king Kuruntiya of Tarḫuntašša.[34]

Later dating

[edit]Based on the shape of the hieroglyphs in the inscriptions of Hartapus, Petra Goedegebuure and Theo van den Hout dated them to the 8th century BCE.[35] Therefore, John Osborne and Michele Massa have contested the interpretations of Weeden and Hawkins[36][37] because the various monuments of the alleged Ḫartapus II portrayed him in ways that did not distinguish him from the purported Ḫartapus II|: this practice did not follow the known reuse of the monuments of earlier similarly named rulers, and instead conflated the two Ḫartapus while diminishing the achievents of Ḫartapus II in his own inscriptions by contrasting him unfavourably with the Ḫartapus I despite reusing his monuments, wordings and titles.[38]

Furthermore, the relief of Ḫartapus at Kızıldağ depicted him in an Assyrianising artistic style, such as his body's proportions, his beard and hairstyle as well as his dress, his hat with folded earmuffs, his upwards pointed shoes, the shape of the bowl and the way he holds it, while the imagery of the enthroned king used in the relief was common throughout the Iron Age Syro-Anatolian region, including the Katumuwa stele of Zincirli Höyük and a relief from the South Gate of Karatepe-Aslantaş; this imagery was related to the depictions of seated royalty from the Neo-Assyrian Empire, which include the image of the queen Libbāli-šarrat in the gardens of Nineveh.[39][40][41]

The art style of the relief, such as Ḫartapus's tripartite beard, him holding the bowl with the tips of this fingers, and his hairstyle, reflected influence from Neo-Assyrian royal depictions from the reigns of Ashurnasirpal II and Shalmaneser III, which was also visible in the reliefs of the king Kilamuwa of Samʾal.[42]

Moreover, Ḫartapus is not mentioned in any of the records of the Neo-Assyrian Empire which started mentioning the Tabalian region during the reign of its king Tiglath-pileser III. Meanwhile, Ḫartapus claimed to have conquered Phrygia, which would have been impossible during the time of its expansion under its king Midas during late the 8th century BCE.[43][6]

Therefore, Osborne and Massa have concluded that the various inscriptions refer to a single Ḫartapus, son of Mursilis, who reigned during the early 8th century BCE,[44] before Midas had become the king of Phrygia.[45]

Life

[edit]Ḫartapus was the son of one Mursilis.[20][46][47]

Reign

[edit]The inscriptions of Ḫartapus were largely concentrated in the Konya-Karaman Plain, suggesting that this area was the core territory of his kingdom,[48][49] which appears to have been centred around the site corresponding to present-day Türkmen-Karahöyük,[50][51] where was located Ḫartapus's royal residence.[52]

The Konya-Karaman Plain within which the kingdom of Ḫartapus was located formed the western part of the group of kingdoms referred by the Neo-Assyrian Empire as the Tabalian region,[53][54] although it was unlikely but not impossible that the Neo-Assyrians had any specific knowledge of the region of Ḫartapus's kingdom.[55]

Unlike the later part of his reign, the earliest monuments of Ḫartapus did not contain the titles of "Great King" and "Hero."[51]

Monuments

[edit]Several Hieroglyphic Luwian inscriptions by Ḫartapus are recorded:[56]

- five are recorded from Mount Kızıldağ;

- two are recorded from Mount Karadağ;

- one is recorded from Türkmen-Karahöyük;

- one is recorded from Burunkaya.[57]

The inscriptions of Ḫartapus are characterised by archaic orthography and palaeography and the use of aediculae similar to imperial Hittite ones from the 13th century BCE,[15][16][47] which is a feature that they shared with the Topada inscription of Wasusarmas of Tabal.[58]

Ḫartapus had built a step monument at Kızıldağ,[59] where inscriptions celebrate his foundation of a settlement at that site.[50] Ḫartapus had also built a monument on mount Karadağ, which might have been meant to parallel the one at Kızıldağ,[60] and where his inscriptions were dedicated to the storm-god Tarḫunzas of Heaven and to the Divine Great Mountain, which was likely Mount Karadağ itself.[61]

The capital city of Ḫartapus, corresponding to present-day Türkmen-Karahöyük, was located close to the mounts Karadağ and Kızıldağ, which were likely peak sanctuaries where Ḫartapus conducted rituals,[62][63] that is sacred sites connected to that capital city, and these three sites were mutually visible with each other.[64][50][60]

The building of monuments on the mounts might therefore have been part of a policy by Ḫartapus to monumentalise these ritual landscapes within and around his capital, similarly to similar arrangements during the Hittite Empire at Hattuša, Zippalanda and Mount Daha, and Šarišša and Lake Šupitaššu.[65][60]

Thus, the monuments at Mount Kızıldağ and Karadağ fitted the common Bronze and Iron Age Anatolian tradition of connecting capital cities to landscape monuments through ritual processions led by the kings and religious officials. The site of Mount Kızıldağ also provided attendees with a spectacular view, which made it an ideal site for ritual ceremonies.[66]

The Kızıldağ monuments of Ḫartapus also include a rock relief representing him seated on a high-backed throne with a footstool under his feet, bearded and long-haired, wearing a peaked cap and a long robe, and holding a bowl in his right hand and a stick in his left hand.[20][21][16][50][67][57] This relief was unusual with respect to traditional Hittite imagery since normally only gods were represented as seated figures while kings were never depicted as such;[68] it was instead modelled on a Neo-Assyrian model, and represented him celebrating a military victory[69] so as to confirm the legitimation of Hartapus's status as Great King.[70]

War against Phrygia

[edit]In his 1st Türkmen-Karahöyük inscription, Ḫartapus claimed to have conquered the 𔐓𔗬𔗜𔗔 (𔑾𔑶𔗧𔔆[71][72][73]), that is the Muški, with this inscription being the first attestation of the Muški outside of Syro-Mesopotamian sources from the 12th and 7th century BCE.[52][74][4][75] These Muska referred to the kingdom of Phrygia prior to its period of expansionism under the reign of Midas,[49] and this conflict between the kingdom of Ḫartapus and Phrygia appears to have resulted from a rivalry between these two polities which preceded by several decades the reign of Ḫartapus.[76]

The kingdom of Ḫartapus was however not powerful enough to have conquered early Phrygia, that is the territory of the Sakarya-Porsuk basin, and the 1st Türkmen-Karahöyük inscription instead recorded Hartapus's defeat of a raid from the region of the Phrygian city of Gordion.[77]

The 1st Türkmen-Karahöyük inscription, which records a victory by him against thirteen kings and the building or capture of ten fortress, is similar in content, as well as in its writing style and shape of its hieroglyphs to the Topada inscription of the king Wasusarmas of Tabal,[52][57] which describes Wasusarmas's war against eleven kings,[78] with the inscriptions of both Ḫartapus and Wasusarmas possibly depicting different conflicts within the same war opposing an eastern Syro-Hittite coalition to a western Phrygian coalition.[79]

Ḫartapus's and Wasusarmas's descriptions of their own respective wars against the Phrygians suggest that there might also have been a direct connection between these two kings.[79]

The 1st Karadağ and 4th Kızıldağ inscriptions of Ḫartapus include the boast that he had "conquered every country" (𔔆𔗣𔔴𔑾𔐞𔕰,[7][80][81] wattaniya punada muwatta kwis at Kızıldağ,[81] and 𔔆𔗣𔕰𔗔𔔴𔐝𔐞,[7][82][83] wattaniya punada kwis muwatta[83] at Karadağ) which was a rare claim in Anatolian inscriptions from both the Bronze and Early Iron Ages.[84][85] The repetition of this claim in these two inscriptions suggests that they both described the same conflict.[84]

Some regions to the east of the Sultan Daği corresponding to the Lake Eber and the lower Kaystros river up to the area of Burunkaya might have been part of the kingdom of Ḫartapus.[86]

New titulature

[edit]In his inscriptions following his victory on Muska,[51] Ḫartapus referred himself as the "Great King" and used a royal cartouche topped by a winged disc, which were derived from the royal tradition of the Hittite Empire. After the end of the Hittite Empire, these titles are only attested to have been used by the kings of Karkamiš, the king Wasusarmas of Tabal and his father Tuwaddis, and Ḫartapus and his father Mursilis.[79][34]

Thus, Ḫartapus was attempting to connect himself to the Hittite royal dynasty.[87][34] Moreover, the kingdom of Ḫartapus appears to have been a direct successor state of the kingdom of Tarḫuntašša, and Ḫartapus might therefore also have tried to symbolically link himself to the king Kuruntiya of Tarḫuntašša.[87][34]

Therefore, like the king Wasusarmas of Tabal, Ḫartapus also used traditional Hittite name and titles, showing that, despite Tabal and the kingdom of Ḫartapus being located in the western peripheries of the post-Hittite world, they were still fully culturally part of the heritage of the Hittite Empire.[88]

War against Tabal (?)

[edit]The Burunkaya inscription of Ḫartapus was unusual in that, unlike his other inscriptions which were located within a 30 kilometre diameter territory in the Konya Plain, it was located 130 kilometres away from the capital of Ḫartapus, and 30 kilometres away from the Suvasa, Göstesin and Topada inscriptions of Wasusarmas of Tabal, 9 kilometres to the east of the Aksaray inscription of Kiyakiyas of Šinuḫtu, and 70 kilometres to the north-west of the Bor and Niğde inscriptions of Warpalawas II of Tuwana, with Kiyakiyas and Warpalawas II having both been allies of Wasusarmas in his war against the country of Prizuwanda.[60]

The Burunkaya inscription was thus within the Tabalian territory, and its contents refer to a military victory; meanwhile, Wasusarmas's Topada inscription mentions the king of Prizuwanda placing his border on a mountain which might have been the Hasandağ volcano, and it also describes the cavalry of Wasusarmas crossing a river which might have been the Melendiz River.[89]

This has led to the suggestion of a tentative identification between Ḫartapus and the king of Prizuwanda mentioned in Wasusarmas's Topada inscription. According to this proposal, the Türkmen-Karahöyük inscription might have been Ḫartapus's description of the same war that is the subject of the Topada inscription, and therefore painted Ḫartapus as the victor of this war while Wasusarmas claimed the victory in his Topada inscription.[90][91][57] According to this tentative identification, the 13 kings mentioned in the 1st Türkmen-Karahöyük inscription of Ḫartapus might have been a coalition of Tabalian rulers.[34]

If Ḫartapus was identical with the king of Prizuwanda, he would have ruled some time between c. 750 and c. 725 BCE, thus making him a contemporary of Wasusarmas of Tabal, in which case the peak of his power would have occurred immediately before the Phrygian king Midas's attempts to expand into Ḫiyawa after c. 720 BCE.[51]

Archaeology

[edit]Due to the large number of archaeological sites in the Konya Plain which had remained unexcavated, in 2017 the archaeologists Michele Massa, Christoph Bachhuber and Fatma Şahin set up the Konya Regional Archaeological Survey Project to study the settlement history of this region.[92]

Massa, Bacchuber and Şahin visited the large höyük at the site of Türkmen-Karahöyük when the Konya Regional Archaeological Survey Project survey started in 2017 and 2018, and recognised it as the largest site in the Konya Plain and its main urban centre in the Bronze and Iron Ages, after which the Türkmen-Karahöyük Intensive Survey Project was started by the archaeologist James Osborne as a sub-project of the Konya Regional Archaeological Survey Project.[93]

In 2018, a local former discovered a royal stele commissioned by Ḫartapus and inscribed in Hieroglyphic Luwian near the site of Turkmen-Karahoyuk, and he informed the researchers of the Türkmen-Karahöyük Intensive Survey Project in the summer of 2019.[94]

References

[edit]- ^ Hawkins 2000b, p. 437-438.

- ^ Hawkins 2000c, p. 433-437.

- ^ Massa & Osborne 2022, p. 86-88.

- ^ a b Payne 2023, p. 870.

- ^ Massa & Osborne 2022, p. 87.

- ^ a b Summers 2023, p. 111.

- ^ a b c d Hawkins 2000b, p. 438.

- ^ a b Hawkins 2000c, p. 433.

- ^ a b Oreshko 2017, p. 62.

- ^ Massa et al. 2019, 01:16:09-01:17:06.

- ^ Oreshko 2021, p. 89-90.

- ^ Kryszeń 2023a.

- ^ Kryszeń 2023b.

- ^ Massa et al. 2019, 00:18:01-00:19:04.

- ^ a b c Oreshko 2017, p. 48.

- ^ a b c d D'Alfonso & Pedrinazzi 2021, p. 131.

- ^ a b Weeden 2023, p. 929-930.

- ^ Bryce 2012, p. 313.

- ^ Oreshko 2017, p. 49.

- ^ a b c Bryce 2009, p. 391.

- ^ a b Bryce 2012, p. 22.

- ^ D'Alfonso & Pedrinazzi 2021, p. 136.

- ^ Bryce 2012, p. 145.

- ^ Oreshko 2017, p. 48-49.

- ^ Bryce 2012, p. 28-29.

- ^ Oreshko 2021, p. 85.

- ^ Oreshko 2017, p. 55.

- ^ Oreshko 2017, p. 57-58.

- ^ Oreshko 2021, p. 81-83.

- ^ Oreshko 2017, p. 59.

- ^ a b Massa & Osborne 2022, p. 86.

- ^ D'Alfonso & Pedrinazzi 2021, p. 137.

- ^ D'Alfonso & Pedrinazzi 2021, p. 153.

- ^ a b c d e Massa & Osborne 2022, p. 99.

- ^ Massa et al. 2019, 00:37:14-00:37:44.

- ^ Massa & Osborne 2022, p. 87-96.

- ^ Massa & Osborne 2022, p. 100.

- ^ Massa & Osborne 2022, p. 100-101.

- ^ D'Alfonso & Pedrinazzi 2021, p. 135.

- ^ D'Alfonso & Pedrinazzi 2021, p. 138.

- ^ Massa & Osborne 2022, p. 93.

- ^ D'Alfonso & Pedrinazzi 2021, p. 146-148.

- ^ Goedegebuure et al. 2020, p. 41.

- ^ Massa & Osborne 2022, p. 88-89.

- ^ Summers 2023, p. 111-112.

- ^ Bryce 2012, p. 21.

- ^ a b Weeden 2023, p. 929.

- ^ Oreshko 2021, p. 90.

- ^ a b Massa & Osborne 2022, p. 98.

- ^ a b c d Massa & Osborne 2022, p. 91.

- ^ a b c d Massa & Osborne 2022, p. 101.

- ^ a b c Osborne et al. 2020, p. 20.

- ^ Massa et al. 2019, 00:13:51-00:.

- ^ Osborne et al. 2020, p. 2.

- ^ Weeden 2023, p. 921-922.

- ^ Weeden 2023, p. 928-929.

- ^ a b c d Weeden 2023, p. 996.

- ^ Weeden 2010, p. 46-47.

- ^ Massa & Osborne 2022, p. 94-95.

- ^ a b c d Massa & Osborne 2022, p. 96.

- ^ Massa et al. 2019, 00:20:35-00:20:45.

- ^ Massa et al. 2019, 00:19:31-00:19:43.

- ^ Massa et al. 2019, 00:20:45-00:21:16.

- ^ Massa et al. 2019, 00:31:37-00:31:50.

- ^ Massa et al. 2019, 00:30:26-00:30:45.

- ^ Massa et al. 2019, 00:30:05-00:30:45.

- ^ Massa & Osborne 2022, p. 91-92.

- ^ D'Alfonso & Pedrinazzi 2021, p. 139.

- ^ D'Alfonso & Pedrinazzi 2021, p. 144.

- ^ D'Alfonso & Pedrinazzi 2021, p. 151.

- ^ Massa et al. 2019, 00:35:38-00:35:54.

- ^ Massa et al. 2019, 00:35:59-00:37:14.

- ^ Goedegebuure et al. 2020, p. 30.

- ^ Massa & Osborne 2022, p. 96-97.

- ^ Payne 2023, p. 879.

- ^ Osborne et al. 2020, p. 22.

- ^ Summers 2023, p. 112.

- ^ Summers 2023, p. 122.

- ^ a b c D'Alfonso & Pedrinazzi 2021, p. 150.

- ^ Hawkins 2000c, p. 435.

- ^ a b Yakubovich, Ilya; Arkhangelskiy, Timofey. "KIZILDAĞ 4". Annotated Corpus of Luwian Texts. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ Hawkins 2000c, p. 436.

- ^ a b Yakubovich, Ilya; Arkhangelskiy, Timofey. "KARADAĞ 1". Annotated Corpus of Luwian Texts. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ a b Massa & Osborne 2022, p. 89.

- ^ Oreshko 2017, p. 50.

- ^ Oreshko 2021, p. 90-91.

- ^ a b Massa et al. 2019, 00:58:22-00:59:22.

- ^ Weeden 2023, p. 998.

- ^ Massa & Osborne 2022, p. 98-98.

- ^ Massa & Osborne 2022, p. 98-99.

- ^ Summers 2023, p. 114.

- ^ Massa et al. 2019, 00:15:11-00:15:45.

- ^ Massa et al. 2019, 00:21:24-00:22:30.

- ^ Massa et al. 2019, 00:26:48-00:28:40.

Sources

[edit]- Bryce, Trevor (2009). The Routledge Handbook of the Peoples and Places of Ancient Western Asia: From the Early Bronze Age to the Fall of the Persian Empire. London, United Kingdom: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-39485-7.

- Bryce, Trevor (2012). The World of The Neo-Hittite Kingdoms: A Political and Military History. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199-21872-1.

- D'Alfonso, Lorenzo; Pedrinazzi, Matteo (2021). "Forgetting an Empire, Creating a New Order: Trajectories of Rock-cut Monuments from Hittite into Post-Hittite Anatolia, and the Afterlife of the "Throne" of Kızıldağ". In Ben-Dov, Jonathan; Rojas, Felipe (eds.). Afterlives of Ancient Rock-cut Monuments in the Near East: Carvings in and out of Time. Culture and History of the Ancient Near East. Vol. 123. Leiden, Netherlands: BRILL. pp. 114–160. ISBN 978-9-004-46208-3.

- Goedegebuure, Petra; van den Hout, Theo; Osborne, James; Massa, Michele; Bachhuber, Christoph; Şahin, Fatma (2020). "TÜRKMEN-KARAHÖYÜK 1: a new Hieroglyphic Luwian inscription from Great King Hartapu, son of Mursili, conqueror of Phrygia". Anatolian Studies: Journal of the British Institute at Ankara. 70. Cambridge University Press on behalf of the British Institute at Ankara: 29–43. doi:10.1017/S0066154620000022. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- Hawkins, John David [in German] (2000b). Inscriptions of the Iron Age, Part 2: Text: Amuq, Aleppo, Hama, Tabal, Assur Letters, Miscellaneous, Seals, Indices. Corpus of Hieroglyphic Luwian Inscriptions. Vol. 1. Berlin, Germany; New York City, United States: Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-110-10864-4.

- Hawkins, John David [in German] (2000c). Inscriptions of the Iron Age, Part 3: Plates. Corpus of Hieroglyphic Luwian Inscriptions. Vol. 1. Berlin, Germany; New York City, United States: Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-110-10864-4.

- Kryszeń, A. (2023a). "Ḫarputa". Hittite Toponyms. University of Mainz; University of Würzburg. Retrieved 7 April 2024.

- Kryszeń, A. (2023b). "Ḫarputauna". Hittite Toponyms. University of Mainz; University of Würzburg. Retrieved 7 April 2024.

- Massa, Michele; Osborne, James F.; Goedegebuure, Petra; van den Hout, Theo (2019). A New Iron Age Kingdom in Anatolia (Video lecture). Chicago, United States: Oriental Institute. Retrieved 10 April 2024.

- Massa, Michele; Osborne, James F. (2022). "On the Identity of Hartapu". Altorientalische Forschungen [Ancient Near Eastern Research]. 49 (1). Walter de Gruyter: 85–103. doi:10.1515/aofo-2022-0006. Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- Oreshko, Rostyslav (2017). "Hartapu and the Land of Maša: A New Look at the KIZILDAĞ-KARADAĞ Group". Altorientalische Forschungen [Ancient Near Eastern Research]. 44 (1). Walter de Gruyter: 47–67. doi:10.1515/aofo-2017-0007. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- Oreshko, Rostislav (2021). "The onager kings of Anatolia: Hartapus, Gordis, Muška and the steppe strand in early Phrygian culture". Kadmos. Zeitschrift für vor- und frühgriechische Epigraphik [Kadmos: Journal of Pre- and Early Greek Epigraphy]. 59 (1–2). Walter de Gruyter: 77–128. doi:10.1515/kadmos-2020-0005. Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- Osborne, James F.; Massa, Michele; Şahin, Fatma; Erpehlivan, Hüseyin; Bachhuber, Christoph (2020). "The city of Hartapu: results of the Türkmen-Karahöyük Intensive Survey Project". Anatolian Studies: Journal of the British Institute at Ankara. 70. Cambridge University Press on behalf of the British Institute at Ankara: 1–27. doi:10.1017/S0066154620000046. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- Payne, Annick (2023). "The Kingdom of Phrygia". In Radner, Karen; Moeller, Nadine; Potts, Daniel T. (eds.). The Age of Assyria. The Oxford History of the Ancient Near East. Vol. 4. New York City, United States: Oxford University Press. pp. 865–911. ISBN 978-0-190-68763-2.

- Summers, Geoffrey D. (2023). "Resizing Phrygia: Migration, State and Kingdom". Altorientalische Forschungen [Ancient Near Eastern Research]. 50 (1). Walter de Gruyter: 107–128. doi:10.1515/aofo-2023-0009. Retrieved 25 July 2024.

- Weeden, Mark (2010). "Tuwati and Wasusarma: Imitating the Behaviour of Assyria". Iraq. 72. British Institute for the Study of Iraq: 39–61. doi:10.1017/S0021088900000589. Retrieved 7 April 2024.

- Weeden, Mark (2023). "The Iron Age States of Central Anatolia and Northern Syria". In Radner, Karen; Moeller, Nadine; Potts, Daniel T. (eds.). The Age of Assyria. The Oxford History of the Ancient Near East. Vol. 4. New York City, United States: Oxford University Press. pp. 912–1026. ISBN 978-0-190-68763-2.