Sequoyah

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Sequoyah | |

|---|---|

ᏍᏏᏉᏯ / ᏎᏉᏯ | |

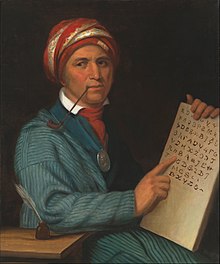

Portrait of Sequoyah by Henry Inman | |

| Born | c. 1770 |

| Died | August 1843 (aged 72–73) |

| Nationality | Cherokee, American |

| Other names | George Guess, George Gist |

| Occupations | |

| Spouse |

Sally Benge (m. 1815) |

| Children | 2 |

Sequoyah (/səˈkwɔɪə/ sə-QUOY-yə; Cherokee: ᏍᏏᏉᏯ, Ssiquoya,[a] or ᏎᏉᏯ, Sequoya,[b] pronounced [seɡʷoja]; c. 1770 – August 1843), also known as George Gist or George Guess, was a Native American polymath and neographer of the Cherokee Nation.

In 1821, Sequoyah completed his Cherokee syllabary, enabling reading and writing in the Cherokee language. One of the first North American Indigenous groups to gain a written language, the Cherokee Nation officially adopted the syllabary in 1825,[2] helping to unify a forcibly divided nation with new ways of communication and a sense of independence.[3] Within a quarter-century, the Cherokee Nation had reached a literacy rate of almost 100%, surpassing that of surrounding European-American settlers.[4]

Sequoyah's creation of the Cherokee syllabary is among the few times in recorded history that an individual member of a pre-literate group created an original, effective writing system. It is believed to have inspired the development of 21 scripts or writing systems used in 65 languages in North America, Africa, and Asia.[5]

Sequoyah was also an important representative for the Cherokee nation; he went to Washington, D.C., to sign two relocation-and-land-trading treaties.[6]

Early life

[edit]Few primary documents describe facts of Sequoyah's life. Some anecdotes were passed down orally, but these often conflict or are vague about specific times and places.

Sequoyah was born in the Cherokee town of Tuskegee, Tennessee, around 1778. James Mooney, a prominent anthropologist and historian of the Cherokee people, quoted a cousin as saying that as a little boy, Sequoyah spent his early years with his mother. In the people's matrilineal kinship system, children were considered born into their mother's family and clan, and her male relatives were most important to their upbringing. His name is believed to come from the Cherokee word siqua meaning "hog". Historian John B. Davis says the name may have been derived from sikwa (either a hog or an opossum) and vi meaning "place, enclosure".[7] This is a reference either to his childhood deformity or to a later injury that left Sequoyah disabled. According to a descendant of his, he was born with the name Gi sqwa ya ("there's a bird inside"). After repeatedly failing to complete his farm duties, his name was changed to Sequoyah ("There's a pig inside").[8]

His mother, Wut-teh, is debated to be either the daughter, sister, or niece of a Cherokee chief. Historians believe her to be related to the chiefs who have been identified as the brothers Old Tassel and Doublehead. John Watts (also known as Young Tassel) was a nephew of the two chiefs, so it is likely that Wut-teh and Watts were related in some fashion. Due to native customs, Sequoyah learned everything from his mother, such as the Cherokee language and his first job of a tradesman.[9]

Sources differ as to the identity of Sequoyah's father. Davis cites Emmet Starr's 1917 book, Early History of the Cherokees, as saying that Sequoyah's father was a Virginian fur trader from Swabia named Nathaniel Guyst, Guist, or Gist. Other sources state that his father could have been an unlicensed German peddler named George Gist, who entered the Cherokee Nation in 1768, married, and fathered a child. Another source identified his father as Nathaniel Gist, son of Christopher Gist, who became a commissioned officer with the Continental Army associated with George Washington during the American Revolution. Gist would have been a man of some social status and financial backing; Josiah C. Nott claimed he was the "son of a Scotchman". The Cherokee Phoenix reported in 1828 that Sequoyah's father was a half-blood and his grandfather a white man.

The New Georgia Encyclopedia presents another version of Sequoyah's origins, from the history Tell Them They Lie: The Sequoyah Myth (1971), by Traveller Bird, who claims to be a Sequoyah descendant. Bird says that Sequoyah was a full-blood Cherokee who always opposed the submission and assimilation of his people into the white man's culture. The encyclopedia noted that Bird presented no documentary evidence of his assertions, but his account has gained some credibility in academic circles.

In any case, the father was absent before Sequoyah was born. Various explanations have been proposed, but the reason is unknown. Wuh-teh did not marry afterward. Sequoyah had no siblings, and his mother raised him alone. According to Davis, Sequoyah never went to school and never learned English. He and Wuh-teh spoke only Cherokee. As a youth, he spent much of his time tending cattle and working in their garden, while his mother ran a trading post.

Sequoyah became lame early in life; how, when, and where are not known. Some reports indicate this may have been caused by injury in battle; others say the cause was a hunting accident. Davis wrote that an early issue of the Cherokee Advocate said he "was the victim of a hydrarthritic trouble of the knee joint, commonly called 'white swelling'." One doctor speculated that he had "anascara [sic]". In any case, lameness prevented him from being a successful farmer or warrior.

Despite his lack of schooling, Sequoyah displayed much natural intelligence. As a child, he had devised and built milk troughs and skimmers for the dairy house that he had constructed. As he grew older and came in contact with more white men, he learned how to make jewelry. He became a noted silversmith, creating various items from the silver coins that trappers and traders carried. He never signed his pieces, so there are none that can be positively identified as his work.

Sequoyah may have taken over his mother's trading post after her death, which Davis claimed occurred about the end of the 18th century. His store became an informal meeting place for Cherokee men to socialize and, especially, drink whiskey. Sequoyah developed a great fondness for alcohol and soon spent much of his time drunk. After a few months, he was rarely seen sober, neglecting his farm and trading business, and spending his money buying liquor by the keg.

Eventually, he took up new interests. He began to draw, then he took up blacksmithing, so he could repair the iron farm implements that had recently been introduced to the area by traders. Self-taught as usual, he made his own tools, forge, and bellows. He was soon doing a good business either repairing items or selling items he had created himself. His spurs and bridle bits were in great demand because he liked to decorate them with silver. Although he maintained his store, he both stopped drinking and stopped selling alcohol.

Sequoyah came to believe that one of white people's many advantages was their written language, which allowed them to expand their knowledge, partake in many forms of media, and have a better network of communication. The Cherokees' disadvantage was having to rely solely on memory. This sparked his interest in wanting to create some form of a written language for the Cherokee nation.[3]

By 1809, Sequoyah is believed to have started developing what became his Cherokee syllabary, in hopes of unifying the Cherokee nation and making them more independent. In 2008, archeologist Kenneth B. Tankersley (Cherokee Nation) of the University of Cincinnati found carvings from the syllabary in a cave in southeastern Kentucky, where Sequoyah is known to have had relatives. This cave was the traditional burial site of a Cherokee chief, Red Bird. Some 15 identifiable Cherokee syllabary symbols were found carved into the limestone, accompanied by a date of 1808 or 1818. In addition, there were petroglyphs that appeared to include ancient Cherokee symbols, in addition to bears, deer and birds.

Move to Alabama

[edit]

It is unclear when Sequoyah moved to Alabama from Tennessee. Many Cherokee began migrating there even before ceding their land around Sequoyah's birthplace in 1819, as they were under continual pressure by European-American settlers. Some sources claim he went with his mother, though there is no confirmed date for her death. Others have stated that it was around 1809 when he started his work on the Cherokee syllabary. Another source claims it was in 1818.[citation needed] However, this date is too late, because Sequoyah was already living in Alabama when he enlisted in the army.[original research?]

In 1813–1814, Sequoyah served as a warrior of the Cherokee Regiment, commanded by Colonel Gideon Morgan, at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend against the "Red Sticks" (Creek, or Muskogee, renegades). His white comrades called him either George Guess or George Gist. The battle was part of the Creek War, launched by traditional Creek during the War of 1812 to assert their power within the people and expel the European-Americans.

While serving, Sequoyah witnessed the disadvantages of not having a written language. Unlike the white soldiers, he and his fellow Cherokee warriors could not write letters to home, read their military orders, or write down any events or thoughts that occurred during their service. This deepened his determination to create a reading and writing system for the Cherokee language.

In 1817, Sequoyah signed a treaty that traded Cherokee land in the southeast for land in Arkansas. But in 1819, he backed out of the treaty, which resulted in the loss of his first Alabama home, leading him to move to Willstown (modern-day Fort Payne), Alabama.[6]

Life after the creation of the syllabary

[edit]Sequoyah completed his syllabary in 1821. It was not immediately accepted by the Cherokee nation, but soon quickly spread. In 1824, Sequoyah was awarded a medal from the Cherokee National Council. This same year, Sequoyah moved from Alabama to Arkansas.

Four years later, he was one of the "Old Settler" delegates that went to Washington, D.C., to sign the treaty that exchanged the Cherokee land in Arkansas for Indian Territory (modern-day Oklahoma). [6]

In 1829, Sequoyah settled in present-day Sallisaw, Oklahoma, with his wife and daughter. In 1838, the Cherokees from the southeast were moved to Indian Territory under Chief John Ross. After this, Sequoyah set out to unite the 16 other Old Settlers with the Ross Party because they already had established their own government. In 1839, Sequoyah and the 16 other Old Settlers and about 15 representatives of the Ross party signed the Act of Union, and a new Cherokee constitution was created.[6][10]

Soon afterward, Sequoyah went to Mexico in search for Cherokees who had migrated there. He was hoping to spread his teachings of the syllabary and convince the migrated Cherokees to move to Indian Territory.[11]

Syllabary and Cherokee literacy

[edit]As a silversmith, Sequoyah dealt regularly with European Americans who had settled in the area. He was impressed by their writing, and referred to their correspondence as "talking leaves". He knew that the papers represented a way to transmit information to other people in distant places, which his fellow American soldiers were able to do but he and other indigenous people could not. A majority of the Cherokee believed that writing was either sorcery, witchcraft, a special gift, or a pretense; Sequoyah accepted none of these explanations. He said that he could invent a way for Cherokees to talk on paper, even though his friends and family thought the idea was absurd.[12]

Creation

[edit]

Around 1809, Sequoyah began creating a system of writing for the Cherokee language. Initially, he pursued a pictograph or logographic system, where every word in the language had a character or symbol. As he failed to plant his fields, endangering his survival, his friends and neighbors thought he had lost his mind. His wife is said to have burned his initial work, believing it to be witchcraft, a notion shared by some of his peers.[9] Ultimately, he realized that this approach was impractical because it would require too many pictures to be remembered.

He then tried making a symbol for each idea, but this also proved impractical.

Sequoyah's third approach was to develop a symbol for each syllable in the language. He used the Bible as a reference, along with adaptations from English, Greek, and Hebrew letters. By 1821, he created a set of 86 symbols (later streamlined to 85), each depicting a consonant-vowel sequence or a syllable of the Cherokee language. The symbols can be written in a chart layout, with the columns being each vowel and the rows being each consonant.[1]

Teaching the syllabary

[edit]Sequoyah's six-year-old daughter, Ayokeh (also spelled Ayoka),[1] was the first person to learn from it. Word spread in their town that they created a new way to communicate, and they were charged and brought to trial by the town chief. Sequoyah and Ayokeh were separated but still communicated by sending letters to one another. Eventually, the warriors presiding over their trial, along with the town, believed that Sequoyah did in fact create a new form of communication, and they all wanted him to teach it to them.[9]

He traveled to the Indian Reserves in the Arkansas Territory, where some Cherokee had settled west of the Mississippi River. To convince the local leaders of the syllabary's usefulness, Sequoyah asked each leader to say a word, which he wrote down and then called his daughter in to read the words back. Intrigued, the leaders allowed Sequoyah to teach a few local people the syllabary. This took several months, during which it was rumored that he might be using the students for sorcery. After completing the lessons, Sequoyah wrote a dictated letter to each student, and read a dictated response. This test convinced the western Cherokee that he had created a practical writing system.

When Sequoyah went to the eastern tribes, he brought a sealed envelope containing a written speech from one of the Arkansas Cherokee leaders. By reading this speech, he convinced the eastern Cherokee to also learn the system. From there it continued to be taught across the Cherokee tribes and towns in the east.[13][14]

By 1830, 90% of Cherokees were literate in their own language.[15] [dubious – discuss]

Use in official documents and print

[edit]

In 1825, the Cherokee Nation officially adopted the writing system, making them one of the first indigenous groups to have a functional written language. By the end of the year, the Bible and hymns were translated into Cherokee. In 1826, the Cherokee National Council commissioned George Lowrey and David Brown to translate and print eight copies of the laws of the Cherokee Nation in the Cherokee language.

In 1828, religious pamphlets, educational materials, and legal documents were all made using the syllabary. A newspaper was founded, the Cherokee Phoenix, the first bilingual newspaper in North America.[16] This newspaper helped keep unity in a dispersed Cherokee Nation by allowing them to have their own network of communication and information.

The syllabary was used for over 100 years to make newspapers, books, religious texts, and almanacs (calendars).[15]

When the Cherokee Nation purchased their first printing press, some of Sequoyah's handwritten symbols needed to be modified. To make the symbols clearer, they were replaced by adaptations from the Roman alphabet and used in the syllabary from that point on.[16]

Life in Indian Territory

[edit]After the Nation accepted his syllabary in 1825, Sequoyah traveled to the Cherokee lands in the Arkansas Territory. There he set up a blacksmith shop and a salt works. He continued to teach the syllabary to anyone who wished.

In 1828, Sequoyah journeyed to Washington, D.C., as part of a delegation to negotiate a treaty for land in the planned Indian Territory. While in Washington, D.C., he sat for a formal portrait painted by Charles Bird King (see image at the top of this article). He holds a copy of the syllabary in his left hand and is smoking a long-stemmed pipe. During his trip, he met representatives of other Native American tribes. Inspired by these meetings, he decided to create a syllabary for universal use among Native American tribes. Sequoyah began to journey into areas of present-day Arizona and New Mexico, to meet with tribes there.

In 1829, Sequoyah moved to a location on Big Skin Bayou, where he built Sequoyah's Cabin that became his home for the rest of his life. It was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1965.[17] (The present-day city of Sallisaw, Oklahoma, developed near here.) The house was operated by the Oklahoma Historical Society until it was purchased by the Cherokee Nation on 9 November 2016.[18]

In 1839, when the Cherokee were bitterly divided over the issue of removal to Indian Territory, Sequoyah joined with Jesse Bushyhead to try to reunite the Cherokee Nation. Sequoyah, representing the Western Cherokee, and Bushyhead representing the Eastern Cherokee, made a joint plea at a tribal council meeting at Takatoka on 20 June 1839. They succeeded in getting a voice vote to hold a new council of all Cherokee to resolve the reunification issues. This is when the Act of Union and a new Cherokee Constitution was created.[19]

Final journey and death

[edit]

Sequoyah dreamed of seeing reunification of the splintered Cherokee Nation. In the spring of 1842, he began a trip to locate other Cherokee bands who were believed to have fled to Mexico and attempted to persuade them to return to the Cherokee Nation, by then mostly residing in Indian Territory. He was accompanied by his son, Teesy (Chusaleta), as well as other Cherokee men identified as Co-tes-ka, Nu-wo-ta-na, Cah-ta-ta, Co-wo-si-ti, John Elijah, and The Worm:[12]

"In the summer of 1842, influenced perhaps by a desire to explore the Western prairies, and become acquainted with his Red Brethren, who roam them free and untrammlled [sic], Se-quo-yah, having loaded several pack horses with goods, visited, in company with a number of Cherokees, the Cumanche Indians. After remaining with them some time, he made his way with a son and two or three other Cherokees, into Northern Mexico, toward Chi-hua-hua, and engaged a while in teaching the Mexicans his native language."

— Mississippi Democrat, Carrollton, Mississippi, Wednesday Morning, January 22, 1845[20]

Sometime between 1843 and 1845, he died due to an estimated respiratory infection during a trip to San Fernando de Rosas in Coahuila, Mexico. A letter written in 1845 by accompanying Cherokee stated that he had died in 1843:[12]

Warren's Trading House, Red River,

April 21st, 1845.

We, the undersigned Cherokees, direct from the Spanish Dominions, do hereby certify that George Guess of the Cherokee Nation, Arkansas, departed this life in the town of San-fernando in the month of August, 1843, and his son Chusaleta is at this time on the Brasos River, Texas, about thirty miles above the falls, and he intends returning home this fall. Given under our hands the day and date written.

STANDING X ROCK (his mark)

STANDING X BOWLES (his mark)

WATCH X JUSTICE (his mark)

WITNESSES

Daniel G. Watson

Jesse Chisholm

The village of San Fernando de Rosas was later renamed as Zaragoza.

In 1938, the Cherokee Nation Principal Chief J. B. Milam funded an expedition to find Sequoyah's grave in Mexico.[21] A party of Cherokee and non-Cherokee scholars embarked from Eagle Pass, Texas, in January 1939. They found a grave site near a fresh water spring in Coahuila, Mexico, but could not conclusively determine the grave site was that of Sequoyah.[22]

In 2011, the Muskogee Phoenix published an article relating a discovery in 1903 of a gravesite in the Wichita Mountains by Hayes and Fancher, which they believed was Sequoyah's. The two men said the site was in a cave and contained a human skeleton with one leg shorter than the other, a long-stemmed pipe, two silver medals, a flintlock rifle and an ax. However, the site was far north of the Mexican border.[23]

International influence

[edit]Sequoyah's work has had international influence, encouraging the development of syllabaries for other, previously unwritten languages. The news that an illiterate Cherokee had created a syllabary spread throughout the United States and its territories. A missionary working in northern Alaska read about it and created a syllabary, what has become known as Cree syllabics. This syllabic writing inspired other indigenous groups across Canada to adapt the syllabics to create writing for their languages.[24]

A literate Cherokee emigrated to Liberia, where he discussed his people's syllabary. A Bassa language speaker of Liberia was inspired to create his own syllabary, and other indigenous groups in West Africa followed suit, creating their own syllabaries.[24]

A missionary in China read about the Cree syllabary and was inspired to follow that example in writing a local language in China. The result of the diffusion of Sequoyah's work has been the development of a total of 21 known scripts, which have been used to write more than 65 languages.[24]

Legacy

[edit]

Due to Sequoyah's contributions and achievements in Cherokee history, there are statues, monuments, museums, and paintings dedicated in his honor across the United States and in various genres.

Science:

- The genus of the coast redwood (Sequoia sempervirens) is named after Sequoyah.[25]

Museums:

- The Carnegie Museum of Art, Architecture Hall, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania Sequoyah Alphabet

- The Sequoyah Birthplace Museum in Monroe County, eastern Tennessee, features his life and Cherokee culture.[26][27]

- In 1964, Sequoyah was inducted into the Hall of Great Westerners of the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum[28]

Paintings and pictures:

- Artist Henry Inman painted a portrait of Sequoyah ca. 1830; it now hangs in the United States National Portrait Gallery[29]

- Sequoyah is pictured on the reverse of the 2017 Sacagawea Dollar coin

Statues and memorials:

- Oklahoma gave a statue of Sequoyah to the National Statuary Hall Collection in 1917. This was the first statue representing a Native American to be placed in the hall. It was created by Vinnie Ream, and is displayed in the Capitol rotunda in Washington, D.C.[30]

- A monument honoring Chief Sequoyah of the Cherokee Nation was dedicated in September 1932 at Calhoun, Georgia.[31] 34.530286°N 84.936806°W

- 1939, a bronze panel with a raised figure of Sequoyah, by Lee Lawrie, was erected in his honor at the Library of Congress

- A Sequoyah memorial was installed in front of the Museum of the Cherokee People in North Carolina

Landmark:

- Sequoyah's Cabin, where he lived during 1829–1844 in the Cherokee Nation, Indian Territory, was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1965 in Oklahoma.

Other:

- On 20 December 1980 the United States Postal Service issued a 19¢ stamp in his honor in the Great Americans series.[32][33]

- Addressing the exalted place Sequoyah holds in Cherokee imagination, the Cherokee composer and musicologist Jack Kilpatrick wrote: "Sequoyah was always in the wilderness. He walked about, but he was not a hunter. I wonder what he was looking for."[22]

- Johnny Cash sang about Sequoyah in his 1964 song "The Talking Leaves".[34]

- Sequoyah briefly appears as a character in Unto These Hills, an outdoor drama that has been performed in Cherokee, NC since 1950.

In 1824, the General Council of the Eastern Cherokee awarded Sequoyah a large silver medal in honor of the syllabary. According to Davis, one side of the medal bore his image surrounded by the inscription in English, "Presented to George Gist by the General Council of the Cherokee for his ingenuity in the invention of the Cherokee Alphabet." The reverse side showed two long-stemmed pipes and the same inscription written in Cherokee. Sequoyah was said to wear the medal throughout the rest of his life and it was buried with him.[citation needed]

-

Statue of Sequoyah in United States Capitol

-

Sequoyah Memorial in front of the Cherokee Museum in North Carolina

-

Bronze panel featuring Sequoyah (1939), by Lee Lawrie. Library of Congress John Adams Building, Washington, D.C.

Contemporary use of Cherokee

[edit]Cherokee is mainly spoken in Oklahoma, North Carolina, and Arkansas; between 1500 and 2100 people actively speak Cherokee in these three main areas. A 2018 survey states that there are 1200 Cherokee speakers who live in the Cherokee nation of Oklahoma, 217 speakers in Eastern North Carolina, and 101 speakers in the United Keetoowah tribe of Cherokee in Arkansas, and that the majority of the Cherokee speakers are people over 40.[15]

Today, in the Cherokee nation (northeast Oklahoma) the syllabary is present on street signs and buildings, is the co-official language with English, and is taught in schools in Oklahoma and North Carolina. The Cherokee nation in the 21st century is trying to integrate this language into people's daily lives. Their goal is to increase immersion programs in schools, encourage older Cherokee members to teach the younger generations, and in 50 years (as of 2008) to have about 80% more fluent Cherokee speakers.[citation needed] People of all ages are taught the language, parents and adults, children in schools, and it is offered at several universities in Oklahoma and North Carolina.[15]

During the time when white settler Indian Removal policies removed indigenous tribes from their lands, a process now known as the Trail of Tears, the use of the Cherokee language dropped dramatically. Use of any indigenous language in the government-run Indian boarding schools resulted in some kind of physical punishment.[35] In the late 20th century, there was a revitalization of the Cherokee language with programs, run by three sovereign Cherokee tribes, and online courses.[16]

Namesake honors

[edit]- A small Mississippian arrowhead found throughout the Midwest and upper south was named Sequoyah by James Brown in 1968.

- The Sequoia trees in California were named Sequoia gigantea in 1847 by Austrian biologist Stephan Endlicher. While it was assumed that this was in honor of Sequoyah, this hypothesis has been questioned.[36] Twenty-first century research in Austria has established that Endlicher, also a published linguist, was familiar with Sequoyah's work.[37] See Chief Sequoyah, a Sequoia tree in Sequoia National Park.

- A crystalline chemical compound found by distilling the needles of the trees was described by Georg Lunge and Th. Steinkaukler in 1880 and named sequoiene.[38]

- The caterpillar of the sequoia-borer moth, a sesiid moth, was named Bembecia sequoiae.[12][39]

- During the Sequoyah Constitutional Convention in 1905, the proposed State of Sequoyah was named in his honor, and merged with Oklahoma Territory to form the new State of Oklahoma in 1906.[12][40][41]

- The name of the district where Sequoyah lived in present-day Oklahoma was changed to the Sequoyah District in 1851. When Oklahoma was admitted to the union in 1906, that area was recorded as Sequoyah County.[12]

- Sequoyah Research Center is dedicated to collecting and archiving Native American writing and literature.

- Mount Sequoyah in the Great Smoky Mountains.

- Mount Sequoyah in Fayetteville, Arkansas, was named in honor of him after the city donated the top of East Mountain to the Methodist Assembly for a retreat.

- The Sequoyah Hills neighborhood of Knoxville, Tennessee.

- The Tennessee Valley Authority Sequoyah Nuclear Plant was named for him.

- The Sequoyah Marina on Norris Lake in Tennessee, upstream from Norris Dam on the Clinch River.

- The USS Sequoia was a yacht officially used for decades by American presidents (it is now privately owned).

- Sequoyah Caverns and Ellis Homestead is in Valley Head, Alabama.[42]

- Sequoyah Country Club, Oakland, California[43]

- Sequoyah Council – A Boy Scouts of America Council located in Northeast Tennessee.

- The Sequoyah Book Award is chosen annually by students in Oklahoma.

- The macOS Sequoia

- Many schools have been named for him, including

- Sequoyah High School, (now a middle school) Doraville, Georgia (Designed by architect John Portman)

- College of the Sequoias, Visalia, California

- Sequoyah High School (Georgia), Canton (Cherokee County), Georgia

- Sequoyah High School (Oklahoma), a Native American boarding school in Tahlequah, Oklahoma

- Sequoyah High School (Tennessee), Madisonville, Tennessee

- Sequoia High School (Redwood City, California)

- Sequoya Elementary School, Tahlequah, Oklahoma

- Sequoyah Elementary School, Shawnee, Oklahoma

- Sequoia Junior High School, Simi Valley, California

- Sequoyah Elementary School, Tulsa, Oklahoma

- Sequoia Elementary School, San Diego, California

- Sequoya Elementary School, Russellville, Arkansas

- Sequoya Middle School, Broken Arrow, Oklahoma

- Sequoya Elementary School, Derwood, Maryland

- Sequoyah School, Pasadena, California

See also

[edit]- History of writing

- Bob Benge, Cherokee leader

- Old Tassel

- List of people who disappeared

- Hastings Shade (1941–2010), fifth-generation direct descendant of Sequoyah

- Tahlonteeskee (Cherokee chief)

- Tenevil

- Uyaquq

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Wilford, John Noble (22 June 2009). "Carvings From Cherokee Script's Dawn". New York Times. Retrieved 23 June 2009.

- ^ "Cherokee Traditions | Language & Literature". www.wcu.edu. Retrieved 4 May 2024.

- ^ a b "Sequoyah | Biography & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- ^ Spring, Joel H. (2004). Deculturalization and the struggle for equality : a brief history of the education of dominated cultures in the United States (Fourth ed.). McGraw. p. 26.

- ^ Unseth, Peter (1 January 2016). "The international impact of Sequoyah's Cherokee syllabary". Written Language & Literacy. 19 (1): 75–93. doi:10.1075/wll.19.1.03uns. ISSN 1387-6732. Retrieved 11 February 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Sequoyah | The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture". www.okhistory.org. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- ^ Davis, John B. (1930). "The Life and Work of Sequoyah". Chronicles of Oklahoma. 8 (2): 149–180.

- ^ Vaughn, Trista (8 August 2018). ""Searching for Sequoyah" interviews UKB Member". United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians.

- ^ a b c "Sequoyah and the Creation of the Cherokee Syllabary". National Geographic Society. 13 November 2019. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- ^ Chavez, Will (26 August 2014). "1839 Cherokee Constitution born from Act of Union". cherokeephoenix.org. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- ^ "Sequoyah". Encyclopedia of Alabama. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Davis, John B. (1930). "The Life and Work of Sequoyah". Chronicles of Oklahoma. 8 (2). Archived from the original on 28 October 2017. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- ^ G. C. (13 August 1820). "Invention of the Cherokee Alphabet". Cherokee Phoenix. Vol. 1, no. 24.

- ^ Boudinot, Elias (1 April 1832). "Invention of a New Alphabet". American Annals of Education.

- ^ a b c d "Cherokee language, writing system and pronunciation". omniglot.com. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- ^ a b c "Cherokee language | Description & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- ^ Joseph Scott Mendinghall (9 December 1975), National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: Sequoyah's Cabin (pdf), National Park Service and Accompanying 4 photos from 1975. (1.11 MB)

- ^ Indian Country Today November 2016

- ^ Chavez, Will (26 August 2014). "1839 Cherokee Constitution born from Act of Union". cherokeephoenix.org. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- ^ "Se-quo-yah, or George Guess". Mississippi Democrat. 22 January 1845.

- ^ J. B. Milam, McFarlin Library, University of Tulsa. Archived 11 January 2006 at the Wayback Machine Libraries & Cultures: Bookplate Archive. 2001 (retrieved 23 June 2009)

- ^ a b Meredith, Howard L. (1985).Bartley Milam: Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation. Muskogee, OK: Indian University Press, p. 47. ISBN 0-940392-17-8

- ^ Mullins, Jonita (13 November 2011). "Sequoyah's gravesite remains unknown". Muskogee Phoenix. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- ^ a b c Unseth, Peter (20 December 2016). "The international impact of Sequoyah's Cherokee syllabary". Written Language & Literacy. 19 (1): 75–93. doi:10.1075/wll.19.1.03uns.

- ^ Muleady-Mecham, Nancy E. (August 2017). "Endlicher and Sequoia: Determination of the Etymological Origin of the Taxon". Bulletin, Southern California Academy of Sciences. 116 (2): 137–146. doi:10.3160/soca-116-02-137-146.1. S2CID 89925020.

- ^ Simlot, Vinay (8 November 2022). "After decades, Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians asks federal government to return land". WBIR News 10. Retrieved 9 November 2022.

- ^ "Sequoyah Museum: The Sequoyah Birthplace Museum".

- ^ "Hall of Great Westerners". National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- ^ "Sequoyah". npg.si.edu. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- ^ "Explore Capitol Hill". Architect of the Capitol. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ^ "Monument honoring Chief Sequoyah of the Cherokee Indian Nation. Calhoun, Georgia. September 1932". Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographic Archive. Georgia State University Library. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- ^ "Georgia on Stamps". GeorgiaInfo. 20 November 2014. Archived from the original on 20 November 2014. Retrieved 18 August 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Sequoyah". National Postal Museum. 8 May 2020. Retrieved 18 August 2021.

- ^ "Songs of Renown: Johnny Cash "The Talking Leaves"". thestringer.com.au. 4 December 2015.

- ^ Lowe, John (October 2002). "Cherokee Self-Reliance". Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 13 (4): 287–295. doi:10.1177/104365902236703. ISSN 1043-6596. PMID 12325243. S2CID 30299719.

- ^ Lowe, Gary D. 2012. Endlicher's sequence: the naming of the genus Sequoia. Fremontia 40, nos. 1 & 2: 25–35.

- ^ Muleady-Mecham, Nancy. "Endlicher and Sequoia: Determination of the Entymological Origin of the Taxon Sequoia". Bulletin of the Southern California Academy of Sciences. Occidental College. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- ^ Gesellschaft, Deutsche chemische (1 July 1880). "Berichte der Deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft zu Berlin".

- ^ Scheidt, Laurel. Hiking Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks. Guilford, CT: Globe Pequot Press, 2002: 68. ISBN 978-0-7627-1122-2 (retrieved through Google books, 23 June 2009)

- ^ Mize, Richard, "Sequoyah Convention Archived 2013-10-16 at the Wayback Machine," Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. (accessed May 30, 2010)

- ^ Wilson, Linda D., "Statehood Movement," Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. (accessed May 30, 2010)

- ^ "Sequoyah Caverns and Ellis Homestead".

- ^ "Welcome to Sequoyah Country Club". Retrieved 2 September 2010.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bender, Margaret. (2002) Signs of Cherokee Culture: Sequoyah's Syllabary in Eastern Cherokee Life. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Feeling, Durbin. Cherokee-English Dictionary: Tsalagi-Yonega Didehlogwasdohdi. Tahlequah, Oklahoma: Cherokee Nation, 1975: xvii

- Holmes, Ruth Bradley; Betty Sharp Smith (1976). Beginning Cherokee: Talisgo Galiquogi Dideliquasdodi Tsalagi Digoweli. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-1362-6.

- Foreman, Grant, Sequoyah, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, OK, 1938.

- Langguth, A. J. Driven West: Andrew Jackson and the Trail of Tears to the Civil War. New York, Simon & Schuster. 2010. ISBN 978-1-4165-4859-1.

- McKinney, Thomas and Hall, James, History of the Indian Tribes of North America. (Philadelphia, PA, 1837–1844).

- McLoughlin, William G., After the Trail of Tears: The Cherokees' Struggle for Sovereignty 1839–1880. University of North Carolina Press. Chapel Hill. 1993. ISBN 0-8078-2111-X.

- Scancarelli, Janine (2007). "Cherokee Writing". In Daniels, Peter T.; Bright, William (eds.). The world's writing systems. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 587–592. ISBN 978-0-195-07993-7.

External links

[edit]- "Invention of the Cherokee Alphabet" Archived 22 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Cherokee Phoenix, 13 August 1828

- "Sequoyah", Tiro Typeworks

- "Sequoyah (aka George Gist)", a North Georgia Notable

- The Cherokee Nation Official Website

- "The Official Cherokee Font" at the Cherokee Nation Official Website

- . The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

- "Sequoyah", NCpedia

- 1770s births

- 1843 deaths

- 1840s missing person cases

- 18th-century Native Americans

- 19th-century American inventors

- American blacksmiths

- American writers with disabilities

- American silversmiths

- Creators of writing systems

- Cherokee Nation people (1794–1907)

- Cherokee Nation politicians (1794–1907)

- Missing person cases in Mexico

- Native Americans in the War of 1812

- People from Knox County, Tennessee

- People from Tennessee in the War of 1812

- People of the Creek War

- Native American tribal government officials in Indian Territory

- Cherokee Nation military personnel (1794–1907)

- American politicians with disabilities