Beta Tauri

| Observation data Epoch J2000 Equinox J2000 | |

|---|---|

| Constellation | Taurus |

| Pronunciation | /ɛlˈnæθ/[1] or /ˈɛlnæθ/[2] |

| Right ascension | 05h 26m 17.51312s[3] |

| Declination | +28° 36′ 26.8262″[3] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 1.65[4] |

| Characteristics | |

| Spectral type | B7III[5] |

| U−B color index | −0.49[4] |

| B−V color index | −0.13[4] |

| Astrometry | |

| Radial velocity (Rv) | 9.2[6] km/s |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: +22.76[3] mas/yr Dec.: −173.58[3] mas/yr |

| Parallax (π) | 24.36 ± 0.34 mas[3] |

| Distance | 134 ± 2 ly (41.1 ± 0.6 pc) |

| Absolute magnitude (MV) | −1.42[7] |

| Details | |

| Mass | 5.0±0.1[8] M☉ |

| Radius | 4.82±0.34[9] – 5.47±0.24[10] R☉ |

| Luminosity | 564±20[10] L☉ |

| Surface gravity (log g) | 3.63[10] cgs |

| Temperature | 13,600±100[9] K |

| Metallicity [Fe/H] | +0.2[10] dex |

| Rotational velocity (v sin i) | 59[11] km/s |

| Age | 100±10[8] Myr |

| Other designations | |

| Database references | |

| SIMBAD | data |

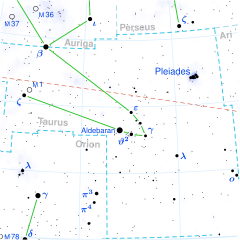

Beta Tauri is the second-brightest star in the constellation of Taurus. It has the official name Elnath; Beta Tauri is the current Bayer designation, which is Latinised from β Tauri and abbreviated Beta Tau or β Tau. The original designation of Gamma Aurigae is now rarely used. It is a chemically peculiar B7 giant star, 134 light years away from the Sun with an apparent magnitude of 1.65.

Nomenclature

[edit]This star has two Bayer designations: β Tauri (Latinised to Beta Tauri) and γ Aurigae (Latinised to Gamma Aurigae). Ptolemy considered the star to be shared by Auriga, and Johann Bayer assigned it a designation in both constellations. When the modern constellation boundaries were fixed in 1930, the designation γ Aurigae largely dropped from use.[12]

The traditional name Elnath, variously El Nath or Alnath, comes from the Arabic word النطح an-naţħ, meaning "the butting" (i.e. the bull's horns). As in many other Arabic star names, the article ال is transliterated literally as el, yet overwhelmingly in Arabic pronunciation it is assimilated to the n, meaning it is omitted. In 2016, the International Astronomical Union organized a Working Group on Star Names (WGSN)[13] to catalog and standardize proper names for stars. The WGSN's first bulletin of July 2016[14] included a table of the first two batches of names approved by the WGSN; which included Elnath for this star.[15]

In Chinese, 五車 (Wǔ Chē), meaning Five Chariots, refers to an asterism consisting of β Tauri, ι Aurigae, Capella, β Aurigae and θ Aurigae.[16] Consequently, the Chinese name for β Tauri itself is 五車五 (Wǔ Chē Wǔ; English: Fifth of the Five Chariots.)[17]

Physical properties

[edit]The absolute magnitude of Beta Tauri is −1.34, similar to another star in Taurus, Maia in the Pleiades star cluster. Like Maia, β Tauri is a B-class giant with a luminosity 700 times solar (L☉).[18] It has evolved to become a giant star, larger and cooler than when it was on the main sequence.[19] However, being approximately 130 light-years distant compared to Maia's estimated 360 light-years, β Tauri ranks as the second-brightest star in the constellation.

It is a mercury-manganese star, a type of non-magnetic chemically peculiar star with unusually large signatures of some heavy elements in its spectrum.[11] Relative to the Sun, β Tauri is notable for a high abundance of manganese, but little calcium and magnesium.[18][20] However, the lack of strong mercury signatures, together with notably high levels of silicon and chromium, have led some authors to give other classifications, including as a "SrCrEu star" or even an Ap star.[21][22] Its limb-darkened angular diameter has been measured at 1.090±0.076 mas. At a distance of 41.1 pc, this corresponds to a linear radius of 4.82±0.34 R☉.[9]

At the southern edge of the narrow plane of the Milky Way Galaxy a few degrees west of the galactic anticenter, β Tauri figures (appears) as a foreground object south of many nebulae and star clusters such as M36, M37, and M38.[23] It is 5.39 degrees north of the ecliptic, still few enough to be occultable by the Moon. Such occultations occur when the Moon's ascending node is near the March equinox, as in 2007. Most are visible only in the Southern Hemisphere, because the star is at the northern edge of the lunar occultation zone – but rarely as far north as southern California.[24]

Companions

[edit]A faint star is, angularly from our viewpoint, close enough for astronomers to consider, and guides to mention, the pair as a double star. This visual companion, BD+28°795B, has a position angle of 239 degrees and is separated from the main star by 33.4 arcseconds (″).[25][26] Six angularly closer, even fainter stars have been found in a search for brown dwarf and planetary companions – all considered background objects.[27]

A very close companion was reported from lunar occultation measurements at a distance of 0.1″, but not confirmed by other observers. Radial velocity measurements indicate that Beta Tauri is a single-lined spectroscopic binary, but there is no published information about the companion or orbit.[28][9]

References

[edit]- ^ "Alnath". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Kunitzsch, Paul; Smart, Tim (2006). A Dictionary of Modern star Names: A Short Guide to 254 Star Names and Their Derivations (2nd rev. ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Sky Pub. ISBN 978-1-931559-44-7.

- ^ a b c d e Van Leeuwen, F. (2007). "Validation of the new Hipparcos reduction". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 474 (2): 653–664. arXiv:0708.1752. Bibcode:2007A&A...474..653V. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078357. S2CID 18759600. Vizier catalog entry

- ^ a b c Ducati, J. R. (2002). "VizieR Online Data Catalog: Catalogue of Stellar Photometry in Johnson's 11-color system". CDS/ADC Collection of Electronic Catalogues. 2237: 0. Bibcode:2002yCat.2237....0D.

- ^ Garrison, R. F; Gray, R. O (1994). "The late B-type stars: Refined MK classification, confrontation with stromgren photometry, and the effects of rotation". The Astronomical Journal. 107: 1556. Bibcode:1994AJ....107.1556G. doi:10.1086/116967.

- ^ Evans, D. S (1967). "The Revision of the General Catalogue of Radial Velocities". Determination of Radial Velocities and Their Applications. 30: 57. Bibcode:1967IAUS...30...57E.

- ^ Anderson, E.; Francis, Ch. (2012). "XHIP: An extended hipparcos compilation". Astronomy Letters. 38 (5): 331. arXiv:1108.4971. Bibcode:2012AstL...38..331A. doi:10.1134/S1063773712050015. S2CID 119257644.

- ^ a b Janson, Markus; et al. (August 2011). "High-contrast Imaging Search for Planets and Brown Dwarfs around the Most Massive Stars in the Solar Neighborhood". The Astrophysical Journal. 736 (2): 89. arXiv:1105.2577. Bibcode:2011ApJ...736...89J. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/736/2/89. S2CID 119217803.

- ^ a b c d Gordon, Kathryn D.; Gies, Douglas R.; Schaefer, Gail H.; Huber, Daniel; Ireland, Michael (2019). "Angular Sizes, Radii, and Effective Temperatures of B-type Stars from Optical Interferometry with the CHARA Array". The Astrophysical Journal. 873 (1): 91. Bibcode:2019ApJ...873...91G. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ab04b2. S2CID 125181833.

- ^ a b c d Baines, Ellyn K.; Thomas Armstrong, J.; Clark, James H.; Gorney, Jim; Hutter, Donald J.; Jorgensen, Anders M.; Kyte, Casey; Mozurkewich, David; Nisley, Ishara; Sanborn, Jason; Schmitt, Henrique R.; Van Belle, Gerard T. (2021). "Angular Diameters and Fundamental Parameters of Forty-four Stars from the Navy Precision Optical Interferometer". The Astronomical Journal. 162 (5): 198. arXiv:2211.09030. Bibcode:2021AJ....162..198B. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/ac2431.

- ^ a b Ghazaryan, S; Alecian, G (2016). "Statistical analysis from recent abundance determinations in HgMn stars". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 460 (2): 1912. Bibcode:2016MNRAS.460.1912G. doi:10.1093/mnras/stw911.

- ^ Ian Ridpath. "Bayer's Uranometria and Bayer letters". Retrieved 2017-11-27.

- ^ "IAU Working Group on Star Names (WGSN)". Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ^ "Bulletin of the IAU Working Group on Star Names, No. 1" (PDF). Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ^ "IAU Catalog of Star Names". Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ^ (in Chinese) 中國星座神話, written by 陳久金. Published by 台灣書房出版有限公司, 2005, ISBN 978-986-7332-25-7.

- ^ (in Chinese) 香港太空館 - 研究資源 - 亮星中英對照表 Archived 2011-01-30 at the Wayback Machine, Hong Kong Space Museum. Accessed on line November 23, 2010.

- ^ a b Kaler, James B. "ELNATH (Beta Tauri)". University of Illinois. Retrieved 2010-03-07.

- ^ Knyazeva, L. N; Kharitonov, A. V (2000). "The Normal Energy Distributions in Stellar Spectra: Giants and Supergiants". Astronomy Reports. 44 (8): 548. Bibcode:2000ARep...44..548K. doi:10.1134/1.1306355. S2CID 120800469.

- ^ Heacox, W. D. (1979). "Chemical abundances in Hg-Mn stars". Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 41: 675. Bibcode:1979ApJS...41..675H. doi:10.1086/190637.

- ^ Chen, P. S; Liu, J. Y; Shan, H. G (2017). "A New Photometric Study of Ap and Am Stars in the Infrared". The Astronomical Journal. 153 (5): 218. Bibcode:2017AJ....153..218C. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/aa679a.

- ^ Bychkov, V. D; Bychkova, L. V; Madej, J (2009). "Catalogue of averaged stellar effective magnetic fields - II. Re-discussion of chemically peculiar a and B stars". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 394 (3): 1338. Bibcode:2009MNRAS.394.1338B. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2008.14227.x. S2CID 120268049.

- ^ Nemiroff, R.; Bonnell, J., eds. (5 March 2010). "Deep Auriga". Astronomy Picture of the Day. NASA. Retrieved 2010-03-07.

- ^ "Skywatcher's Diary". Abrams Planetarium. Archived from the original on August 30, 2007.

- ^ "CCDM (Catalog of Components of Double & Multiple stars (Dommanget+ 2002)". VizieR. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 2010-03-07.

- ^ "Al Nath". Alcyone Bright Star Catalogue. Retrieved 2010-03-07.

- ^ Janson, Markus; Bonavita, Mariangela; Klahr, Hubert; Lafrenière, David; Jayawardhana, Ray; Zinnecker, Hans (2011). "High-contrast Imaging Search for Planets and Brown Dwarfs around the Most Massive Stars in the Solar Neighborhood". The Astrophysical Journal. 736 (2): 89. arXiv:1105.2577. Bibcode:2011ApJ...736...89J. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/736/2/89. S2CID 119217803.

- ^ Adelman, S. J.; Caliskan, H.; Gulliver, A. F.; Teker, A. (2006). "Elemental abundance analyses with DAO spectrograms". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 447 (2): 685–690. Bibcode:2006A&A...447..685A. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20053581.

External links

[edit]- Jim Kaler's Stars: Elnath

- NASA Astronomy Picture of the Day: Image of Elnath (5 March 2010)