Atomic number

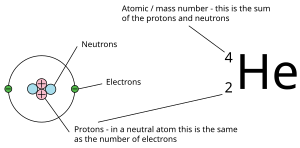

The atomic number or nuclear charge number (symbol Z) of a chemical element is the charge number of its atomic nucleus. For ordinary nuclei composed of protons and neutrons, this is equal to the proton number (np) or the number of protons found in the nucleus of every atom of that element. The atomic number can be used to uniquely identify ordinary chemical elements. In an ordinary uncharged atom, the atomic number is also equal to the number of electrons.

For an ordinary atom which contains protons, neutrons and electrons, the sum of the atomic number Z and the neutron number N gives the atom's atomic mass number A. Since protons and neutrons have approximately the same mass (and the mass of the electrons is negligible for many purposes) and the mass defect of the nucleon binding is always small compared to the nucleon mass, the atomic mass of any atom, when expressed in daltons (making a quantity called the "relative isotopic mass"), is within 1% of the whole number A.

Atoms with the same atomic number but different neutron numbers, and hence different mass numbers, are known as isotopes. A little more than three-quarters of naturally occurring elements exist as a mixture of isotopes (see monoisotopic elements), and the average isotopic mass of an isotopic mixture for an element (called the relative atomic mass) in a defined environment on Earth determines the element's standard atomic weight. Historically, it was these atomic weights of elements (in comparison to hydrogen) that were the quantities measurable by chemists in the 19th century.

The conventional symbol Z comes from the German word Zahl 'number', which, before the modern synthesis of ideas from chemistry and physics, merely denoted an element's numerical place in the periodic table, whose order was then approximately, but not completely, consistent with the order of the elements by atomic weights. Only after 1915, with the suggestion and evidence that this Z number was also the nuclear charge and a physical characteristic of atoms, did the word Atomzahl (and its English equivalent atomic number) come into common use in this context.

The rules above do not always apply to exotic atoms which contain short-lived elementary particles other than protons, neutrons and electrons.

History

[edit]In the 19th century, the term "atomic number" typically meant the number of atoms in a given volume.[1][2] Modern chemists prefer to use the concept of molar concentration.

In 1913, Antonius van den Broek proposed that the electric charge of an atomic nucleus, expressed as a multiplier of the elementary charge, was equal to the element's sequential position on the periodic table. Ernest Rutherford, in various articles in which he discussed van den Broek's idea, used the term "atomic number" to refer to an element's position on the periodic table.[3][4] No writer before Rutherford is known to have used the term "atomic number" in this way, so it was probably he who established this definition.[5][6]

After Rutherford deduced the existence of the proton in 1920, "atomic number" customarily referred to the proton number of an atom. In 1921, the German Atomic Weight Commission based its new periodic table on the nuclear charge number and in 1923 the International Committee on Chemical Elements followed suit.[7]

The periodic table and a natural number for each element

[edit]

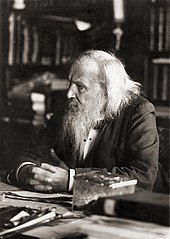

The periodic table of elements creates an ordering of the elements, and so they can be numbered in order.[8]: 222 Dmitri Mendeleev arranged his first periodic tables (first published on March 6, 1869) in order of atomic weight ("Atomgewicht").[9] However, in consideration of the elements' observed chemical properties, he changed the order slightly and placed tellurium (atomic weight 127.6) ahead of iodine (atomic weight 126.9).[9][10] This placement is consistent with the modern practice of ordering the elements by proton number, Z, but that number was not known or suspected at the time.

A simple numbering based on atomic weight position was never entirely satisfactory. In addition to the case of iodine and tellurium, several other pairs of elements (such as argon and potassium, cobalt and nickel) were later shown to have nearly identical or reversed atomic weights, thus requiring their placement in the periodic table to be determined by their chemical properties.[8]: 222 However the gradual identification of more and more chemically similar lanthanide elements, whose atomic number was not obvious, led to inconsistency and uncertainty in the periodic numbering of elements at least from lutetium (element 71) onward (hafnium was not known at this time).

The Rutherford-Bohr model and van den Broek

[edit]

In 1911, Ernest Rutherford gave a model of the atom in which a central nucleus held most of the atom's mass and a positive charge which, in units of the electron's charge, was to be approximately equal to half of the atom's atomic weight, expressed in numbers of hydrogen atoms. This central charge would thus be approximately half the atomic weight (though it was almost 25% different from the atomic number of gold (Z = 79, A = 197), the single element from which Rutherford made his guess). Nevertheless, in spite of Rutherford's estimation that gold had a central charge of about 100 (but was element Z = 79 on the periodic table), a month after Rutherford's paper appeared, Antonius van den Broek first formally suggested that the central charge and number of electrons in an atom were exactly equal to its place in the periodic table (also known as element number, atomic number, and symbolized Z). This eventually proved to be the case.

Moseley's 1913 experiment

[edit]

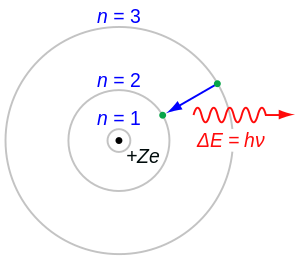

The experimental position improved dramatically after research by Henry Moseley in 1913.[11] Moseley, after discussions with Bohr who was at the same lab (and who had used Van den Broek's hypothesis in his Bohr model of the atom), decided to test Van den Broek's and Bohr's hypothesis directly, by seeing if spectral lines emitted from excited atoms fitted the Bohr theory's postulation that the frequency of the spectral lines be proportional to the square of Z.

To do this, Moseley measured the wavelengths of the innermost photon transitions (K and L lines) produced by the elements from aluminium (Z = 13) to gold (Z = 79) used as a series of movable anodic targets inside an x-ray tube.[12] The square root of the frequency of these photons (x-rays) increased from one target to the next in an arithmetic progression. This led to the conclusion (Moseley's law) that the atomic number does closely correspond (with an offset of one unit for K-lines, in Moseley's work) to the calculated electric charge of the nucleus, i.e. the element number Z. Among other things, Moseley demonstrated that the lanthanide series (from lanthanum to lutetium inclusive) must have 15 members—no fewer and no more—which was far from obvious from known chemistry at that time.

Missing elements

[edit]After Moseley's death in 1915, the atomic numbers of all known elements from hydrogen to uranium (Z = 92) were examined by his method. There were seven elements (with Z < 92) which were not found and therefore identified as still undiscovered, corresponding to atomic numbers 43, 61, 72, 75, 85, 87 and 91.[13] From 1918 to 1947, all seven of these missing elements were discovered.[14] By this time, the first four transuranium elements had also been discovered, so that the periodic table was complete with no gaps as far as curium (Z = 96).

The proton and the idea of nuclear electrons

[edit]In 1915, the reason for nuclear charge being quantized in units of Z, which were now recognized to be the same as the element number, was not understood. An old idea called Prout's hypothesis had postulated that the elements were all made of residues (or "protyles") of the lightest element hydrogen, which in the Bohr-Rutherford model had a single electron and a nuclear charge of one. However, as early as 1907, Rutherford and Thomas Royds had shown that alpha particles, which had a charge of +2, were the nuclei of helium atoms, which had a mass four times that of hydrogen, not two times. If Prout's hypothesis were true, something had to be neutralizing some of the charge of the hydrogen nuclei present in the nuclei of heavier atoms.

In 1917, Rutherford succeeded in generating hydrogen nuclei from a nuclear reaction between alpha particles and nitrogen gas,[15] and believed he had proven Prout's law. He called the new heavy nuclear particles protons in 1920 (alternate names being proutons and protyles). It had been immediately apparent from the work of Moseley that the nuclei of heavy atoms have more than twice as much mass as would be expected from their being made of hydrogen nuclei, and thus there was required a hypothesis for the neutralization of the extra protons presumed present in all heavy nuclei. A helium nucleus was presumed to have four protons plus two "nuclear electrons" (electrons bound inside the nucleus) to cancel two charges. At the other end of the periodic table, a nucleus of gold with a mass 197 times that of hydrogen was thought to contain 118 nuclear electrons in the nucleus to give it a residual charge of +79, consistent with its atomic number.

Discovery of the neutron makes Z the proton number

[edit]All consideration of nuclear electrons ended with James Chadwick's discovery of the neutron in 1932. An atom of gold now was seen as containing 118 neutrons rather than 118 nuclear electrons, and its positive nuclear charge now was realized to come entirely from a content of 79 protons. Since Moseley had previously shown that the atomic number Z of an element equals this positive charge, it was now clear that Z is identical to the number of protons of its nuclei.

Chemical properties

[edit]Each element has a specific set of chemical properties as a consequence of the number of electrons present in the neutral atom, which is Z (the atomic number). The configuration of these electrons follows from the principles of quantum mechanics. The number of electrons in each element's electron shells, particularly the outermost valence shell, is the primary factor in determining its chemical bonding behavior. Hence, it is the atomic number alone that determines the chemical properties of an element; and it is for this reason that an element can be defined as consisting of any mixture of atoms with a given atomic number.

New elements

[edit]The quest for new elements is usually described using atomic numbers. As of 2024, all elements with atomic numbers 1 to 118 have been observed. Synthesis of new elements is accomplished by bombarding target atoms of heavy elements with ions, such that the sum of the atomic numbers of the target and ion elements equals the atomic number of the element being created. In general, the half-life of a nuclide becomes shorter as atomic number increases,[citation needed] though undiscovered nuclides with certain "magic" numbers of protons and neutrons may have relatively longer half-lives and comprise an island of stability.

A hypothetical element composed only of neutrons, neutronium, has also been proposed and would have atomic number 0,[16] but has never been observed.

See also

[edit]- Atomic theory

- Chemical element – Chemical substance not composed of simpler ones

- Effective nuclear charge – Measurement in atomic physics

- Effective atomic number (compounds and mixtures) – Approximate atomic number calculated for materials with many elements

- Even and odd atomic nuclei – Nuclear physics classification method

- History of the periodic table – Development of the table of chemical elements

- List of chemical elements

- Mass number – Number of heavy particles in the atomic nucleus

- Neutron number – The number of neutrons in a nuclide

- Neutron–proton ratio – Ratio of neutrons to protons in an atomic nucleus

- Prout's hypothesis – Early model of the atom that did not account for mass defect

References

[edit]- ^ Leopold Gmelin (1848). Hand-book of Chemistry, p. 52: "...the specific gravity divided by the atomic weight gives the Atomic number, that is to say, the number of atoms in a given volume.

- ^ James Curtis Booth, Campbell Morfit (1890). The Encyclopedia of Chemistry, Practical and Theoretical p.271: "The atomic number of a substance is its specific gravity, divided by its combining weight or equivalent. [...] the spec. grav. of a substance must be the number of atoms in a given volume, multiplied by their combining weight."

- ^ Ernest Rutherford (March 1914). "The Structure of the Atom". Philosophical Magazine. 6. 27: 488–498.

It is obvious from the consideration of the cases of hydrogen and helium, where hydrogen has one electron and helium two, that the number of electrons cannot be exactly half the atomic weight in all cases. This has led to an interesting suggestion by van den Broek that the number of units of charge on the nucleus, and consequently the number of external electrons, may be equal to the number of the elements when arranged in order of increasing atomic weight.

- ^ Ernest Rutherford (11 December 1913). "The Structure of the Atom". Nature. 92 (423).

The original suggestion of van der Broek that the charge on the nucleus is equal to the atomic number and not to half the atomic weight seems to me very promising.

- ^ Eric Scerri (2020). The Periodic Table: Its Story and Its Significance, p. 185

- ^ Helge Kragh (2012). Niels Bohr and the Quantum Atom, p. 33

- ^ Helge Kragh (2012). Niels Bohr and the Quantum Atom, p. 34

- ^ a b Pais, Abraham (2002). Inward bound: of matter and forces in the physical world (Reprint ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press [u.a.] ISBN 978-0-19-851997-3.

- ^ a b The Periodic Table of Elements Archived 18 August 2023 at the Wayback Machine, American Institute of Physics

- ^ The Development of the Periodic Table Archived 26 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Royal Society of Chemistry

- ^ Ordering the Elements in the Periodic Table Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Royal Chemical Society

- ^ Moseley, H.G.J. (1913). "XCIII.The high-frequency spectra of the elements". Philosophical Magazine. Series 6. 26 (156): 1024–1034. doi:10.1080/14786441308635052. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 July 2023. Retrieved 12 December 2023.

- ^ Eric Scerri, A tale of seven elements, (Oxford University Press 2013) ISBN 978-0-19-539131-2, p.47

- ^ Scerri chaps. 3–9 (one chapter per element)

- ^ Ernest Rutherford | NZHistory.net.nz, New Zealand history online Archived 1 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Nzhistory.net.nz (19 October 1937). Retrieved on 2011-01-26.

- ^ von Antropoff, A. (1926). "Eine neue Form des periodischen Systems der Elementen". Zeitschrift für Angewandte Chemie (in German). 39 (23): 722–725. Bibcode:1926AngCh..39..722V. doi:10.1002/ange.19260392303.