Young's interference experiment

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2015) |

Young's interference experiment, also called Young's double-slit interferometer, was the original version of the modern double-slit experiment, performed at the beginning of the nineteenth century by Thomas Young. This experiment played a major role in the general acceptance of the wave theory of light.[1] In Young's own judgement, this was the most important of his many achievements.

Theories of light propagation in the 17th and 18th centuries

[edit]During this period, many scientists proposed a wave theory of light based on experimental observations, including Robert Hooke, Christiaan Huygens and Leonhard Euler.[2] However, Isaac Newton, who did many experimental investigations of light, had rejected the wave theory of light and developed his corpuscular theory of light according to which light is emitted from a luminous body in the form of tiny particles.[3] This theory held sway until the beginning of the nineteenth century despite the fact that many phenomena, including diffraction effects at edges or in narrow apertures, colours in thin films and insect wings, and the apparent failure of light particles to crash into one another when two light beams crossed, could not be adequately explained by the corpuscular theory which, nonetheless, had many eminent supporters, including Pierre-Simon Laplace and Jean-Baptiste Biot.

Young's work on wave theory

[edit]

While studying medicine at Göttingen in the 1790s, Young wrote a thesis on the physical and mathematical properties of sound[4] and in 1800, he presented a paper to the Royal Society (written in 1799) where he argued that light was also a wave motion. His idea was greeted with a certain amount of skepticism because it contradicted Newton's corpuscular theory. Nonetheless, he continued to develop his ideas. He believed that a wave model could much better explain many aspects of light propagation than the corpuscular model:

A very extensive class of phenomena leads us still more directly to the same conclusion; they consist chiefly of the production of colours by means of transparent plates, and by diffraction or inflection, none of which have been explained upon the supposition of emanation, in a manner sufficiently minute or comprehensive to satisfy the most candid even of the advocates for the projectile system; while on the other hand all of them may be at once understood, from the effect of the interference of double lights, in a manner nearly similar to that which constitutes in sound the sensation of a beat, when two strings forming an imperfect unison, are heard to vibrate together.[5]

In 1801, Young presented a famous paper to the Royal Society entitled "On the Theory of Light and Colours"[7] which describes various interference phenomena. In 1803, he described his famous interference experiment.[8] Unlike the modern double-slit experiment, Young's experiment reflects sunlight (using a steering mirror) through a small hole, and splits the thin beam in half using a paper card.[6][8][9] He also mentions the possibility of passing light through two slits in his description of the experiment:

Supposing the light of any given colour to consist of undulations of a given breadth, or of a given frequency, it follows that these undulations must be liable to those effects which we have already examined in the case of the waves of water and the pulses of sound. It has been shown that two equal series of waves, proceeding from centres near each other, may be seen to destroy each other's effects at certain points, and at other points to redouble them; and the beating of two sounds has been explained from a similar interference. We are now to apply the same principles to the alternate union and extinction of colours.

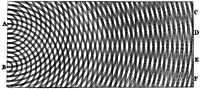

In order that the effects of two portions of light may be thus combined, it is necessary that they be derived from the same origin, and that they arrive at the same point by different paths, in directions not much deviating from each other. This deviation may be produced in one or both of the portions by diffraction, by reflection, by refraction, or by any of these effects combined; but the simplest case appears to be, when a beam of homogeneous light falls on a screen in which there are two very small holes or slits, which may be considered as centres of divergence, from whence the light is diffracted in every direction. In this case, when the two newly formed beams are received on a surface placed so as to intercept them, their light is divided by dark stripes into portions nearly equal, but becoming wider as the surface is more remote from the apertures, so as to subtend very nearly equal angles from the apertures at all distances, and wider also in the same proportion as the apertures are closer to each other. The middle of the two portions is always light, and the bright stripes on each side are at such distances, that the light coming to them from one of the apertures, must have passed through a longer space than that which comes from the other, by an interval which is equal to the breadth of one, two, three, or more of the supposed undulations, while the intervening dark spaces correspond to a difference of half a supposed undulation, of one and a half, of two and a half, or more.

From a comparison of various experiments, it appears that the breadth of the undulations constituting the extreme red light must be supposed to be, in air, about one 36 thousandth of an inch, and those of the extreme violet about one 60 thousandth ; the mean of the whole spectrum, with respect to the intensity of light, being about one 45 thousandth. From these dimensions it follows, calculating upon the known velocity of light, that almost 500 millions of millions of the slowest of such undulations must enter the eye in a single second. The combination of two portions of white or mixed light, when viewed at a great distance, exhibits a few white and black stripes, corresponding to this interval: although, upon closer inspection, the distinct effects of an infinite number of stripes of different breadths appear to be compounded together, so as to produce a beautiful diversity of tints, passing by degrees into each other. The central whiteness is first changed to a yellowish, and then to a tawny colour, succeeded by crimson, and by violet and blue, which together appear, when seen at a distance, as a dark stripe; after this a green light appears, and the dark space beyond it has a crimson hue; the subsequent lights are all more or less green, the dark spaces purple and reddish; and the red light appears so far to predominate in all these effects, that the red or purple stripes occupy nearly the same place in the mixed fringes as if their light were received separately.[5]

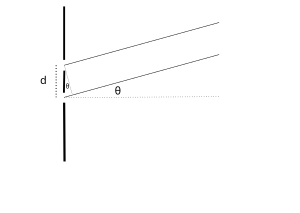

The figure shows the geometry for a far-field viewing plane. It is seen that the relative paths of the light travelling from the two points sources to a given point in the viewing plane varies with the angle θ, so that their relative phases also vary. When the path difference is equal to an integer number of wavelengths, the two waves add together to give a maximum in the brightness, whereas when the path difference is equal to half a wavelength, or one and a half etc., then the two waves cancel, and the intensity is at a minimum.

The linear separation (distance) - between fringes (lines with maximum brightness) on the screen is given by the equation :

where is the distance between the slit and screen, is the wavelength of light and is the slit separation as shown in figure.

The angular spacing of the fringes, θf, is then given by

where θf <<1, and λ is the wavelength of the light. It can be seen that the spacing of the fringes depends on the wavelength, the separation of the holes, and the distance between the slits and the observation plane, as noted by Young.

This expression applies when the light source has a single wavelength, whereas Young used sunlight, and was therefore looking at white-light fringes which he describes above. A white light fringe pattern can be considered to be made up of a set of individual fringe patterns of different colours. These all have a maximum value in the centre, but their spacing varies with wavelength, and the superimposed patterns will vary in colour, as their maxima will occur in different places. Only two or three fringes can normally be observed. Young used this formula to estimate the wavelength of violet light to be 400 nm, and that of red light to be about twice that – results with which we would agree today.

In the years 1803–1804, a series of unsigned attacks on Young's theories appeared in the Edinburgh Review. The anonymous author (later revealed to be Henry Brougham, a founder of the Edinburgh Review) succeeded in undermining Young's credibility among the reading public sufficiently that a publisher who had committed to publishing Young's Royal Institution lectures backed out of the deal. This incident prompted Young to focus more on his medical practice and less on physics.[10]

Acceptance of the wave theory of light

[edit]In 1817, the corpuscular theorists at the French Academy of Sciences which included Siméon Denis Poisson were so confident that they set the subject for the next year's prize as diffraction, being certain that a particle theorist would win it.[4] Augustin-Jean Fresnel submitted a thesis based on wave theory and whose substance consisted of a synthesis of the Huygens' principle and Young's principle of interference.[2]

Poisson studied Fresnel's theory in detail and of course looked for a way to prove it wrong being a supporter of the particle theory of light. Poisson thought that he had found a flaw when he argued that a consequence of Fresnel's theory was that there would exist an on-axis bright spot in the shadow of a circular obstacle blocking a point source of light, where there should be complete darkness according to the particle-theory of light. Fresnel's theory could not be true, Poisson declared: surely this result was absurd. (The Poisson spot is not easily observed in everyday situations, because most everyday sources of light are not good point sources. In fact it is readily visible in the defocused telescopic image of a moderately bright star, where it appears as a bright central spot within a concentric array of diffraction rings.)

However, the head of the committee, Dominique-François-Jean Arago thought it was necessary to perform the experiment in more detail. He molded a 2-mm metallic disk to a glass plate with wax.[11] To everyone's surprise he succeeded in observing the predicted spot, which convinced most scientists of the wave-nature of light. In the end, Fresnel won the competition.

After that, the corpuscular theory of light was vanquished, not to be heard of again till the 20th century. Arago later noted that the phenomenon (which is sometimes called the Arago spot) had already been observed by Joseph-Nicolas Delisle[1]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Footnotes

Citations

- ^ a b Heavens, O. S.; Ditchburn, R. W. (1991). Insight into Optics. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-92769-3.

- ^ a b Born, M.; Wolf, E. (1999). Principles of Optics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-64222-4.

- ^ "Magic Without Lies". Cosmos: Possible Worlds. Episode 9. 6 April 2020. National Geographic.

- ^ a b Mason, P. (1981). The Light Fantastic. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-006129-1.

- ^ a b Young, T. (1807). A Course of Lectures on Natural Philosophy and the Mechanical Arts. Vol. 1. William Savage. Lecture 39, pp. 463–464. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.22458.

- ^ a b Rothman, T. (2003). Everything's Relative and Other Fables in Science and Technology. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-20257-8.

- ^ Young, T. (1802). "The Bakerian Lecture: On the Theory of Light and Colours". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 92: 12–48. doi:10.1098/rstl.1802.0004. JSTOR 107113.

- ^ a b "Thomas Young's experiment". www.cavendishscience.org. Archived from the original on 2022-03-31. Retrieved 2017-07-23.

- ^ Veritasium (2013-02-19), The Original Double Slit Experiment, retrieved 2017-07-23

- ^ Robinson, Andrew (2006). The Last Man Who Knew Everything. New York, NY: Pi Press. pp. 115–120. ISBN 0-13-134304-1.

- ^ Fresnel, A. J. (1868). Oeuvres Completes d'Augustin Fresnel: Théorie de la Lumière. Imprimerie impériale. p. 369.