Yoga for women

Modern yoga as exercise has often been taught by women to classes consisting mainly of women. This continued a tradition of gendered physical activity dating back to the early 20th century, with the Harmonic Gymnastics of Genevieve Stebbins in the US and Mary Bagot Stack in Britain. One of the pioneers of modern yoga, Indra Devi, a pupil of Krishnamacharya, popularised yoga among American women using her celebrity Hollywood clients as a lever.

The majority of yoga practitioners in the Western world are women. Yoga has been marketed to women as promoting health and beauty, and as something that could be continued into old age. It has created a substantial market for fashionable yoga clothing. Yoga is now encouraged also for pregnant women.

A gendered activity

[edit]

The yoga author and teacher Geeta Iyengar notes that women in the ancient Vedic period had equal rights to practice the meditational yoga of the time, but that these rights fell away in later periods.[1] The Indologist James Mallinson states that the Gorakhnati yoga order always avoided women, as is enjoined by hatha yoga texts such as the Amritasiddhi, the Hatha Yoga Pradipika, and the Gheranda Samhita; but all the same, women are mentioned as practising yoga, such as using vajroli mudra to conserve menstrual fluid and hence obtain siddhi.[2]

The yoga scholar Mark Singleton notes that there has been a dichotomy between the physical activities of men and women since the start of European gymnastics (with the systems of Pehr Ling and Niels Bukh). Men were "primarily concerned with strength and vigor while women [were] expected to cultivate physical attractiveness and graceful movement."[3] This gendered approach continued as the practice of yoga asanas became popular in the mid-20th century. A masculinised form of yoga grew from Indian nationalism, favouring strength and manliness, and sometimes also a form of religious nationalism, and continues into the 21st century among Hindu nationalists like the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, continuing the tradition of gymnastics and bodybuilding exemplified by early-20th-century figures like K. V. Iyer and Tiruka. The other form emphasises stretching, relaxation, deep breathing, and a more "spiritual" style, continuing a women's tradition of exercise dating back to the Harmonic Gymnastics of Genevieve Stebbins and Mary Bagot Stack.[4]

Alongside the yoga brands, many teachers, for example in England, offer an unbranded "hatha yoga", often mainly to women, creating their own combinations of poses. These may be in flowing sequences (vinyasas), and new variants of poses are often created.[7][8][9] The gender imbalance has sometimes been marked; in Britain in the 1970s, women formed between 70 and 90 per cent of most yoga classes, as well as most of the yoga teachers.[10] The scholar of modern yoga Kimberley J. Pingatore similarly notes that yoga practitioners in the United States are predominantly female, young, affluent, fit, and white.[11] In the United States in 2004, 77 per cent of yoga practitioners were women; in Australia in 2002, the figure was 86 per cent, the majority middle-aged and health-conscious.[12] The imbalance may be increasing: Yoga Journal's survey in 1997 found that a little over 80 percent of readers were female; in 2003, the journal's advertising page reported 89 percent female readership.[13] This is causing yoga to evolve as a female practice, taught by women to women.[14]

Leading "yoginis" (named for the medieval female deities and their worshippers that were so described), women in modern yoga, include Nischala Joy Devi, Donna Farhi, Angela Farmer, Lilias Folan, Sharon Gannon (co-founder of Jivamukti Yoga), Sally Kempton, Gurmukh Kaur Khalsa, Judith Hanson Lasater, Swamini Mayatitananda, Sonia Nelson, Sarah Powers (founder of Insight Yoga), Shiva Rea (founder of Prana Vinyasa yoga), Patricia Sullivan, Rama Jyoti Vernon,[15] and Sadie Nardini (founder of Core Strength Vinyasa Yoga).[16]

History

[edit]Louise Morgan

[edit]In 1936, the journalist Louise Morgan interviewed the rajah of Aundh, Bhawanrao Shriniwasrao Pant Pratinidhi, in the News Chronicle. Her report announced "Surya Namaskars – The Secret of Health", claiming that not only were the rajah and the rani (his wife, the queen) in perfect health (although he was over 70, and she had had eight children), but the 60-year-old wife of the rani's tutor looked younger than her daughters. According to Goldberg, many American mothers secretly but heartily wished that. This was the first time that Surya Namaskar had been sold to Western women.[17]

Indra Devi

[edit]

A pioneer of modern asana-based yoga, Indra Devi (born Eugenie V. Peterson), the Russian pupil of the founder of yoga as exercise, Krishnamacharya, argued that yoga was suitable for well-to-do Indian women: "Yogic exercises since they are non-violent and non-fatiguing are particularly suited to a woman and make her more beautiful."[18]

The historian of modern yoga Elliott Goldberg notes that the normally progressive Devi was effectively arguing for "a gentle yoga for the fairer sex",[18] deprecating the more energetic exercises such as Surya Namaskar.[18] Devi was encouraged by Krishnamacharya to begin teaching yoga in China.[19] In 1939, she opened the first yoga school in Shanghai, continuing to run it for seven years, mainly teaching American women.[20] On her return in 1947, she opened a yoga studio on Sunset Boulevard in Hollywood, teaching yoga to film stars and other celebrities including Greta Garbo, Eva Gabor, Gloria Swanson, Robert Ryan, Jennifer Jones, Ruth St. Denis, Serge Koussevitsky, and the violinist Yehudi Menuhin.[21][22] This famous clientele helped Devi to sell yoga, and her books such as her 1953 Forever Young Forever Healthy, her 1959 Yoga for Americans, and her 1963 Renew Your Life Through Yoga, to a sceptical American public.[23]

Not all her clients were women, but all the same, much of the advice in her books was to women. For example, in Forever Young Forever Healthy, Devi advises her readers that "No make-up can hide a hard line around the mouth, a selfish expression on the face, a spiteful glance in the eyes."[24] She instructs them to stay absolutely quiet and ask themselves if they are as beautiful as they can be; in her view, yoga brought beauty by assisting with peace of mind.[24]

Marcia Moore

[edit]

The American heiress (her father was the founder of Sheraton Hotels) Marcia Moore studied yoga in Calcutta in the 1950s, and trained as a yoga teacher under Swami Vishnudevananda in Canada in 1961; she opened the Sivananda Yoga Vedanta Centre in Boston in 1962.[25] Her classes were, according to the journalist Jess Stearn, "wholly attended by upper-middle-class fortyish housewives".[26] Stearn reflected on why their husbands did not join the classes; he supposed that the men were put off by how easily their wives performed the asanas, and being unfit office workers, felt they would lose face if seen to be less physical than their wives. Moore explained to Stearn that the women were more interested in caring for their bodies than their husbands, since they had been caring for that "package" all their lives, and they didn't want to "see the wrapping wrinkled and spoiled."[27] Goldberg adds that this did not explain why the women chose classes rather than home practice; he suggests that, as well as the skill and motivation that a teacher could provide, going out to a class gave these 1960s housewives an identity of their own, "being involved in an exotic exercise practice with a group of other daring women."[27] They developed their own subculture with yoga books, lectures, classes, friends and a shared uniform of black leotards and stockings, combining a dancer's "hip severity" with a chorus girl's "ostentatious allure".[27]

Britain

[edit]While Devi and Moore were spreading asana-based yoga on the other side of the Atlantic, women in Britain took up the practice from the 1960s, and yoga, in other words asana sessions, became a common option among adult education evening classes. For example, in Birmingham, a local newspaper editor, Wilfred Clark, gave a lecture on yoga to the Workers' Educational Association in 1961, meeting such an enthusiastic response that he proposed yoga classes to the local education authority, and founded in turn the Birmingham Yoga Club, the Midlands Yoga Association, and finally the British Wheel of Yoga in 1965. Yoga groups soon sprang up all over Britain.[28]

Yoga reached London's evening classes in 1967. The Inner London Education Authority (ILEA) stated that classes in "Hatha Yoga (sic)" should not cover the philosophy of Yoga, favouring "Keep Fit" classes in asanas and "pranayamas (sic)" especially for people aged over 40, and expressing concern about the risk of "exhibitionism" and the lack of suitably qualified teachers. The ILEA's Peter McIntosh watched some classes taught by B. K. S. Iyengar, was impressed by his book Light on Yoga, and from 1970 ILEA-approved yoga teacher training was run by one of Iyengar's pupils, Silva Mehta.[10]

Yoga classes grew beyond those of local education authorities when ITV screened Yoga for Health from 1971; it was adopted by more than 40 TV channels in America. The yoga researcher Suzanne Newcombe estimates that the number of people, mainly middle-class women,[a] practising yoga in Britain rose from about 5,000 in 1967 to 50,000 in 1973 and 100,000 by 1979; most of their teachers were also women. With the rise of feminism and being well-educated, middle-class British women were starting to resent being housewives, and given their relative economic freedom, were ready to experiment with new lifestyles such as yoga. Newcombe speculates that their husbands may have found having their wives attending "course on traditionally feminine subjects like flower arranging or cooking ... less threatening and more respectable than employment outside the home."[10] The women saw evening classes as safe, interesting, and a good place to make friends with like-minded people. Further, women in Britain were accustomed to gendered physical education, dating back to Mary Bagot Stack's Women's League of Health and Beauty before the Second World War.[10]

India

[edit]Little is known of many of the women who helped to develop modern yoga in India, but one of Bishnu Charan Ghosh's pupils in Calcutta was Labanya Palit, who published a manual of 40 asanas, Shariram Adyam ("A Healthy Body"), in 1955, a work admired by the poet and polymath Rabindranath Tagore.[30][31]

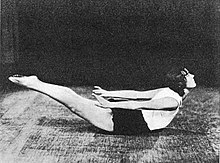

Health and beauty

[edit]Yoga has been marketed to women as something that made them look younger, and that they could carry on learning or teaching into old age, a message taught by books such as Nancy Phelan and Michael Volin's 1963 Yoga for Women: "Most yoga teachers know ... of women who have astonished everyone ... discarding stiffness and tension for suppleness, slimness, serenity and poise".[33] The yoga models in the 1960s and 1970s wore "flattering and sexy fishnet stockings and a tight-fitting leotard top."[10]

Clothing and accessories

[edit]Women's yoga has created a large market for fashionable yoga clothing. Major yoga clothing brands include Lululemon, known for their yoga pants.[34] Sales of athleisure clothing including yoga pants were worth $35 billion in 2014, forming 17 per cent of American clothing sales.[32]

Pregnancy

[edit]

In the 1960s, Krishnamacharya identified asanas suitable for pregnant women.[14] Geeta Iyengar's 1990 A Gem for Women described a yoga practice adapted to women, with sections on yoga in menstruation, pregnancy, and menopause.[35]

Before 1980, few books considered whether yoga was relevant to pregnancy.[10] Since then, numerous books have addressed the subject,[36] including Geeta Iyengar's 2010 Iyengar Yoga for Motherhood,[37] Françoise Barbira Freedman's 2004 Yoga for Pregnancy, Birth, and Beyond,[38] and Leslie Lekos and Megan Westgate's 2014 Yoga For Pregnancy: Poses, Meditations, and Inspiration for Expectant and New Mothers.[39] According to the American Pregnancy Association, yoga increases strength and flexibility in pregnant women, helping them with breathing and relaxation techniques to assist labour.[40]

The practice of yoga asanas has sometimes been advised against during pregnancy, but that advice has been contested by a 2015 study which found no ill-effects from any of 26 asanas investigated. The study examined the effects of the set of asanas on 25 healthy women who were between 35 and 37 weeks pregnant. The authors noted that apart from their experimental findings, they had been unable to find any scientific evidence that supported the previously published concerns, and that on the contrary there was evidence including from systematic review that yoga was suitable for pregnant women, with a variety of possible benefits.[41][42]

Yoginis

[edit]Pioneering female teachers of modern yoga as exercise are sometimes described as yoginis, though the term principally denotes medieval tantric figures, whether goddesses or female practitioners, as recorded in tantric texts and the surviving yogini temples.[43] In her 2006 book Yogini, Janice Gates describes the contributions of leading "yoginis" Nischala Joy Devi, Donna Farhi, Angela Farmer, Lilias Folan, Sharon Gannon (co-founder of Jivamukti Yoga), Gurmukh Kaur Khalsa, Judith Hanson Lasater, Sarah Powers, Shiva Rea, and Rama Jyoti Vernon.[44]

Notes

[edit]- ^ In British usage, the middle class is relatively comfortable, above the working class, well-educated with well-paid jobs.[29]

References

[edit]- ^ Hodges 2007, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Singleton 2010, pp. 160–162.

- ^ Singleton 2010, pp. 157, 160–162.

- ^ Pingatore 2016.

- ^ Murphy, Rosalie (8 July 2014). "Why Your Yoga Class Is So White". The Atlantic.

- ^ Singleton 2010, p. 152.

- ^ Cook, Jennifer (28 August 2007). "Find Your Match Among the Many Types of Yoga". Yoga Journal.

If you are browsing through a yoga studio's brochure of classes and the yoga offered is simply described as 'hatha,' chances are the teacher is offering an eclectic blend of two or more of the styles described above.

- ^ Beirne, Geraldine (10 January 2014). "Yoga: A Beginner's Guide to the Different Styles". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g Newcombe 2007.

- ^ Pingatore 2015; Pingatore 2016.

- ^ Hodges 2007, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Strauss 2005, p. 78.

- ^ a b Hodges 2007, p. 70.

- ^ Gates 2006, passim.

- ^ Friedman, Jennifer D'Angelo (12 April 2017). "Sadie Nardini's Empowering Yoga Sequence for Women in Honor of V-Day". Yoga Journal. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ^ Goldberg 2016, pp. 275–276.

- ^ a b c Goldberg 2016, p. 291.

- ^ Goldberg 2016, p. 343.

- ^ Goldberg 2016, p. 346.

- ^ Martin, Douglas (30 April 2002). "Indra Devi, 102, Dies – Taught Yoga to Stars and Leaders". The New York Times.

- ^ Goldberg 2016, pp. 348, 350.

- ^ Goldberg 2016, p. 350.

- ^ a b Goldberg 2016, p. 352.

- ^ Goldberg 2016, p. 322.

- ^ Goldberg 2016, p. 323.

- ^ a b c Goldberg 2016, p. 324.

- ^ Newcombe 2007; Newcombe 2019.

- ^ "Middle Class". Cambridge Dictionary. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- ^ "The Women of Yoga". Ghosh Yoga. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- ^ Rao, Soumya (31 July 2019). "Filling a gap in history: Who were the Indian women who popularised yoga?". Scroll.in.

- ^ a b DiBlasio, Natalie (30 December 2014). "Retailers Rush to Tap Millennial 'Athleisure' Market". USA Today. McLean, Virginia.

- ^ Newcombe 2007; Phelan & Volin 1979, p. 16.

- ^ Loffredi, Julie. "Stylish Athleticwear and Workout Clothes for Women". Forbes. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- ^ Hodges 2007, p. 71.

- ^ "5 Outstanding Prenatal Yoga Books". Our Family World. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- ^ Iyengar, Keller & Khattab 2010.

- ^ Barbira Freedman 2004.

- ^ Lekos & Westgate 2014.

- ^ "Prenatal Yoga". American Pregnancy Association. Irving, Texas. 28 August 2017. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- ^ Polis, Rachael L.; Gussman, Debra; Kuo, Yen-Hong (2015). "Yoga in Pregnancy". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 126 (6): 1237–1241. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000001137. ISSN 0029-7844. PMID 26551176. S2CID 205467344.

All 26 yoga postures were well-tolerated with no acute adverse maternal physiologic or fetal heart rate changes.

- ^ Curtis, Kathryn; Weinrib, Aliza; Katz, Joel (2012). "Systematic Review of Yoga for Pregnant Women: Current Status and Future Directions". Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2012: 1–13. doi:10.1155/2012/715942. ISSN 1741-427X. PMC 3424788. PMID 22927881.

- ^ Hatley, Shaman (2007). The Brahmayāmalatantra and Early Śaiva Cult of Yoginīs. University of Pennsylvania (PhD Thesis, UMI Number: 3292099). pp. 12–21.

- ^ Gates 2006, pp. whole book (a chapter to each of these women).

Sources

[edit]- Barbira Freedman, Françoise (2004). Yoga for Pregnancy, Birth, and Beyond. London: Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 978-1-4053-0056-8.

- Gates, Janice (2006). Yogini: Women Visionaries of the Yoga World. San Rafael, California: Mandala Publications. ISBN 978-1-932771-88-6.

- Goldberg, Elliott (2016). The Path of Modern Yoga: The History of an Embodied Spiritual Practice. Rochester, Vermont: Inner Traditions. ISBN 978-1-62055-567-5.

- Hodges, Julie (2007). The Practice of Iyengar Yoga by Mid-Aged Women: An Ancient Tradition in a Modern Life (PDF) (PhD thesis). Newcastle, New South Wales: Newcastle University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2019. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

- Iyengar, Geeta S.; Keller, Rita; Khattab, Kerstin (2010). Iyengar Yoga for Motherhood: Safe Practice for Expectant & New Mothers. New York: Sterling. ISBN 978-1-4027-2689-7.

- Lekos, Leslie; Westgate, Megan (2014). Yoga for Pregnancy: Poses, Meditations, and Inspiration for Expectant and New Mothers. New York: Helios Press. ISBN 978-1-62914-362-0.

- Mallinson, James; Singleton, Mark (2017). Roots of Yoga. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-241-25304-5.

- Newcombe, Suzanne (2007). "Stretching for Health and Well-Being: Yoga and Women in Britain, 1960–1980". Asian Medicine. 3 (1): 37–63. doi:10.1163/157342107X207209.

- ——— (2019). Yoga in Britain: Stretching Spirituality and Educating Yogis. Bristol, England: Equinox Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78179-661-0.

- Phelan, Nancy; Volin, Michael (1979) [1963]. Yoga for Women. London: Arrow Books. ISBN 978-0-09-916990-1.

- Pingatore, Kimberley J. (2015). Bodies Bending Boundaries: Religious, Spiritual, and Secular Identities of Modern Postural Yoga in the Ozarks (MA thesis). Springfield, Missouri: Missouri State University.

- ——— (2016). "Review of Selling Yoga: From Counterculture to Pop Culture, by Andrea R. Jain". Religion. 46 (3): 458–461. doi:10.1080/0048721X.2015.1084863. S2CID 147571747.

- Singleton, Mark (2010). Yoga Body: The Origins of Modern Posture Practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195395358.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-539534-1.

- Strauss, Sarah (2005). Positioning Yoga: balancing acts across cultures. Oxford and New York: Berg. ISBN 978-1-85973-739-2. OCLC 290552174.