York City F.C.

| ||||

| Full name | York City Football Club | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nickname(s) | The Minstermen | |||

| Founded | 1922 | |||

| Ground | York Community Stadium | |||

| Capacity | 8,500 | |||

| Coordinates | 53°59′05″N 1°03′10″W / 53.98472°N 1.05278°W | |||

| Owner |

| |||

| Co-chairs |

| |||

| Manager | Adam Hinshelwood | |||

| League | National League | |||

| 2023–24 | National League, 20th of 24 | |||

| Website | https://yorkcityfootballclub.co.uk/ | |||

|

| ||||

York City Football Club is a professional association football club based in the city of York, North Yorkshire, England. The team competes in the National League, the fifth level of the English football league system, as of the 2024–25 season.

Founded in 1922, the club played seven seasons in non-League football before joining the Football League. York played in the Third Division North and Fourth Division until 1959, when they were promoted for the first time. York achieved their best run in the FA Cup in 1954–55, when they met Newcastle United in the semi-final. They fluctuated between the Third and Fourth Divisions, before spending two seasons in the Second Division in the 1970s. York first played at Wembley Stadium in 1993, when they won the Third Division play-off final. At the end of 2003–04, they lost their Football League status after being relegated from the Third Division. The 2011–12 FA Trophy was the first national knockout competition won by York, and they returned to the Football League that season before being relegated back into non-League football in 2016.

York are nicknamed the Minstermen, after York Minster, and the team traditionally play in red kits. They played at Fulfordgate from 1922 to 1932, when they moved to Bootham Crescent, their home for 88 years. This ground had been subject to numerous improvements over the years, but the club lost ownership of it when it was transferred to a holding company in 1999. York bought it back five years later, but the terms of the loan used to do so necessitated a move to a new ground. They moved into their current ground, the York Community Stadium, in 2021. York have had rivalries with numerous clubs, but their traditional rivals are Hull City and Scarborough. The club's record appearance holder is Barry Jackson, who made 539 appearances, while their leading scorer is Norman Wilkinson, with 143 goals.

History

[edit]1922–1946: Foundation and establishment in Football League

[edit]

The club was founded with the formation of the York City Association Football and Athletic Club Limited in May 1922[1] and subsequently gained admission to the Midland League.[2] York ranked in 19th place in 1922–23 and 1923–24,[3] and entered the FA Cup for the first time in the latter.[4] York played in the Midland League for seven seasons, achieving a highest finish of sixth, in 1924–25 and 1926–27.[3] They surpassed the qualifying rounds of the FA Cup for the first time in 1926–27, when they were beaten 2–1 by Second Division club Grimsby Town in the second round.[3] The club made its first serious attempt for election to the Football League in May 1927, but this was unsuccessful as Barrow and Accrington Stanley were re-elected.[5][6] However, the club was successful two years later, being elected to the Football League in June 1929 to replace Ashington in the Third Division North.[7]

York won 2–0 against Wigan Borough in their first match in the Football League,[8] and finished 1929–30 sixth in the Third Division North.[9] Three years later, York only avoided having to seek re-election after winning the last match of 1932–33.[10] In the 1937–38 FA Cup, they eliminated First Division teams West Bromwich Albion and Middlesbrough, and drew 0–0 at home to Huddersfield Town in the sixth round, before losing the replay 2–1 at Leeds Road.[11] York had been challenging for promotion in 1937–38 before faltering in the closing weeks, and in the following season only avoided having to apply for re-election with victory in the penultimate match.[12] They participated in the regional competitions organised by the Football League[13] upon the outbreak of the Second World War in September 1939.[14] York played in wartime competitions for seven seasons,[15] and in 1942 won the Combined Counties Cup.[16]

1946–1981: FA Cup run, promotion and relegations

[edit]

Peacetime football resumed in 1946–47 and York finished the next three seasons in midtable.[3] However, they were forced to apply for re-election for the first time[17] after finishing bottom of the Third Division North in 1949–50.[18] York pursued promotion in 1952–53, before finishing fourth with 53 points, which were new club records in the Football League.[3] The club's longest cup run came when they reached the semi-final of the 1954–55 FA Cup, a campaign in which Arthur Bottom scored eight goals.[19] In the semi-final, York drew 1–1 with Newcastle United at Hillsborough, before being beaten 2–0 at Roker Park in the replay.[19] This meant York had become the first third-tier club to play in an FA Cup semi-final replay.[20] With a 13th-place finish in 1957–58, York became founder members of the Fourth Division, while the clubs finishing in the top half of the North and South sections formed the new Third Division.[21]

York only missed out on the runners-up spot in 1958–59 on goal average,[22] and were promoted for the first time in third place.[3] However, they were relegated from the Third Division after just one season in 1959–60.[23] York's best run in the League Cup came in 1961–62, the competition's second season, after reaching the fifth round.[3] They were beaten 2–1 by divisional rivals Rochdale.[24] York had to apply for re-election for the second time[25] after finishing 22nd in 1963–64,[26] but achieved a second promotion the next season, again in third place in the Fourth Division.[27] York were again relegated after one season, finishing bottom of the Third Division in 1965–66.[28] The club was forced to apply for re-election in three successive seasons, from 1966–67 to 1968–69,[29] after finishing in the bottom four of the Fourth Division in each of those season.[3] York's record of earning promotion every six years was maintained in 1970–71,[3] with a fourth-place finish in the Fourth Division.[30]

York avoided relegation from the Third Division in 1971–72 and 1972–73, albeit only on goal average in both seasons.[31][32] After these two seasons they hit form in 1973–74, when "three up, three down" was introduced to the top three divisions.[33] After being among the leaders most of the season,[34] York were promoted to the Second Division for the first time in third place.[35] The club's highest-ever league placing was achieved in mid October 1974 when York were fifth in the Second Division,[36][37] and they finished 1974–75 in 15th place.[38] York finished in 21st place the following season, and were relegated back to the Third Division.[39] York dropped further still, being relegated in 1976–77 after finishing bottom of the Third Division.[40] The 1977–78 season culminated in the club being forced to apply for re-election for the sixth time,[41] after ranking third from bottom in the Fourth Division.[42] Two midtable finishes followed[43][44] before York made their seventh application for re-election,[45] after they finished bottom of the Fourth Division in 1980–81.[46]

1981–2004: Further promotions and relegation from Football League

[edit]

In 1981–82, York endured a club-record run of 12 home matches without victory, but only missed out on promotion in 1982–83 due to their poor away form in the second half of the season.[47] York won the Fourth Division championship with 101 points in 1983–84,[48] becoming the first Football League team to achieve a three-figure points total in a season.[49] In January 1985, York recorded a 1–0 home victory over First Division Arsenal in the fourth round of the 1984–85 FA Cup, courtesy of an 89th-minute penalty scored by Keith Houchen.[50] They proceeded to draw 1–1 at home with European Cup holders Liverpool in February 1985, but lost 7–0 in the replay at Anfield;[51] York's record cup defeat.[52] The teams met again in the following season's FA Cup, and after another 1–1 home draw, Liverpool won 3–1 in the replay after extra time at Anfield.[53] Their finish of seventh in the Third Division in 1985–86 marked the fifth consecutive season York had improved their end-of-season league ranking.[3]

York only avoided relegation with a draw in the last match of 1986–87,[54] but did go down the following season after finishing second from bottom in the Third Division.[55] In 1992–93, York ended a five-year spell in the Third Division by gaining promotion to the Second Division via the play-offs.[3] Crewe Alexandra were beaten in the play-off final at Wembley Stadium, with a 5–3 penalty shoot-out victory following a 1–1 extra time draw.[56] York reached the Second Division play-offs at the first attempt, but lost 1–0 on aggregate to Stockport County in the semi-final.[57] York recorded a 4–3 aggregate victory in the 1995–96 League Cup second round over the eventual Premier League and FA Cup double winners Manchester United.[58] This included a 3–0 win in the first leg at Old Trafford against a strong United team that included some younger players, and a more experienced United team was unable to overcome the deficit in the second leg, York losing 3–1.[59] They then beat Everton in the second round of the following season's League Cup; they drew the first leg 1–1 at Goodison Park, but won the second leg 3–2 at home.[60]

York were relegated from the Second Division in 1998–99,[61] after dropping into 21st place on the last day of the season.[62] In December 2001, long-serving chairman Douglas Craig put the club and its ground up for sale for £4.5 million, before announcing that the club would resign from the Football League if a buyer was not found.[63][64] Motor racing driver John Batchelor took over the club in March 2002,[65] and by December the club had gone into administration.[66] The Supporters' Trust (ST) bought the club in March 2003[67] after an offer of £100,000 as payment for £160,000 owed in tax was accepted by the Inland Revenue.[68] Batchelor left having diverted almost all of the £400,000 received from a sponsorship deal with Persimmon to his racing team,[69] and having failed to deliver on his promise of having ST members on the board.[70] York failed to win any of their final 20 league fixtures in 2003–04[71] and finished bottom of the Third Division.[72] This meant the club was relegated to the Football Conference, ending 75 years of Football League membership.[73]

2004–present: Return to and relegation from Football League

[edit]

York only avoided relegation late into their first Conference National season in 2004–05,[74] before reaching the play-off semi-final in 2006–07, when they were beaten 2–1 on aggregate by Morecambe.[75] Having only escaped relegation towards the end of 2008–09,[76] York participated in the 2009 FA Trophy final, and were defeated 2–0 by Stevenage Borough at Wembley Stadium.[77] They reached the 2010 Conference Premier play-off final at Wembley Stadium, but were beaten 3–1 by Oxford United.[78] York won their first national knockout competition two years later, after they beat Newport County 2–0 in the 2012 FA Trophy final at Wembley Stadium.[79] A week later they earned promotion to League Two after they beat Luton Town 2–1 at Wembley Stadium in the 2012 Conference Premier play-off final, marking the club's return to the Football League after an eight-year absence.[80]

York only secured survival from relegation late into 2012–13, their first season back in the Football League.[81] They made the League Two play-offs the following season, and were beaten 1–0 on aggregate by Fleetwood Town in the semi-final.[82] However, York were relegated to the National League four years after returning to the Football League,[83] with a bottom-place finish in League Two in 2015–16.[84] York were further relegated to the National League North for the first time in 2016–17;[85] however, they ended the season with a 3–2 win over Macclesfield Town at Wembley Stadium in the 2017 FA Trophy final.[86] The club was promoted back to the National League at the end of the 2021–22 season via the play-offs, with a 2–0 victory over Boston United in the final.[87] The ST purchased JM Packaging's 75% share of the club in July 2022 to regain its 100% shareholding, before transferring 51% of those shares to businessman Glen Henderson, who took over as chairman of the club.[88]

Club identity

[edit]York are nicknamed "the Minstermen", in reference to York Minster.[89] It is believed to have been coined by a journalist who came to watch the team during a successful cup run, and was only first used officially in literature in 1972.[90] Before this, York were known as "the Robins", because of the team's red shirts.[89] They were billed "the Happy Wanderers", after a popular song, at the time of their run in the 1954–55 FA Cup.[91]

For most of the club's history, York have worn red shirts.[92] However, in the club's first season, 1922–23, the kit comprised maroon shirts, white shorts and black socks were worn.[92] Maroon and white striped shirts were worn for three years in the mid 1920s, before the maroon shirts returned.[92] In 1933, York changed their maroon jerseys to chocolate and cream stripes, a reference to the city's association with the confectionery industry.[92] After four years they changed their colours to what were described as "distinctive red shirts", with the official explanation that the striped jerseys clashed with opponents too often.[92] York continued to don red shirts before a two-year spell of wearing all-white kits from 1967 to 1969.[92]

York resumed wearing maroon shirts with white shorts in 1969.[92] To mark their promotion to the Second Division in 1974, a bold white "Y" was added to the shirts, which became known as the "Y-fronts".[92] Red shirts returned in 1978, along with the introduction of navy blue shorts.[92] In 2004, the club dropped navy from the kits and instead used plain red and white,[92] until 2008 when a kit mostly of navy was introduced.[93] For 2007–08, the club brought in a third kit, which comprised light blue shirts and socks, with maroon shorts.[94] A kit with purple shirts was introduced for a one-off appearance in the 2009 FA Trophy final.[95] Red shirts returned in 2010, and have been worn with red, navy blue, light blue and white shorts.[92]

York adopted the city's coat of arms as their crest upon the club's formation,[89] although it only featured on the shirts from 1950 to 1951.[92] In 1959, a second crest was introduced, in the form of a shield that contained York Minster, the White Rose of York and a robin.[89] This crest never appeared on the shirts,[89] but from 1969 to 1973 they bore the letters "YCFC" running upwards from left to right, and from 1974 to 1978 the "Y-fronts" shirts included a stylised badge in which the "Y" and "C" were combined.[92] The shirts bore a new crest in 1978, which depicted Bootham Bar, two heraldic lions and the club name in all-white, and in 1983 this was updated into a coloured version.[92]

When Batchelor took over the club in 2002, the crest was replaced by one signifying the club's new name of "York City Soccer Club" and held a chequered flag motif.[92] After Batchelor's one-year period at the club, the name reverted to "York City Football Club" and a new logo was introduced.[96] It was selected following a supporters' vote held by the club, and the successful design was made by Michael Elgie.[96] The badge features five lions, four of which are navy blue and are placed on a white Y-shaped background.[92] The rest of the background is red with the fifth lion in white, placed between the top part of the "Y".[92]

Tables of kit suppliers and shirt sponsors appear below:[92][97]

| Kit suppliers | ||

|---|---|---|

| Dates | Supplier | |

| 1975–1976 | Umbro | |

| 1976–1982 | Admiral | |

| 1982–1983 | Le Coq Sportif | |

| 1983–1987 | Hobott | |

| 1987–1988 | Rodsport | |

| 1989–1991 | ABC Sport | |

| 1991–1995 | Cavendish Sports | |

| 1995–2001 | Admiral | |

| 2001–2003 | Own brand | |

| 2003–2017 | Nike | |

| 2017–2018 | Avec | |

| 2018–2021 | Under Armour | |

| 2021–2024 | Puma | |

| 2024–present | Hummel | |

| Shirt sponsors | |

|---|---|

| Dates | Sponsor |

| 1981–1983 | Newitt's |

| 1984 | Hansa |

| 1984 | Cameron's |

| 1985–1990 | Hansa |

| 1990–1991 | Flamingo Land |

| 1991–2001 | Portakabin |

| 2001–2003 | York Evening Press |

| 2003–2005 | Phoenix Software |

| 2005–2009 | CLP Industries |

| 2009–2012 | Pryers Solicitors |

| 2012–2019 | Benenden Health |

| 2019–2023 | JM Packaging |

| 2023–present | Titan Wealth Holdings |

Grounds

[edit]Fulfordgate

[edit]

York's first ground was Fulfordgate, which was located on Heslington Lane, Fulford in the south-east of York.[98] With the ground not ready, York played their first two home matches at Mille Crux, Haxby Road, before they took to the field at Fulfordgate for a 4–1 win over Mansfield Town on 20 September 1922.[99] Fulfordgate was gradually improved; terracing replaced banking behind one of the goals, the covered Popular Stand was extended to house 1,000 supporters, and a small seated stand was erected.[98] By the time of York's election to the Football League in 1929, the ground was estimated to hold a capacity of 17,000.[98] However, attendances declined in York's second and third Football League seasons, and the directors blamed this on the ground's location.[100] In April 1932, York's shareholders voted to move to Bootham Crescent, which had been vacated by York Cricket Club, on a 21-year lease.[101] This site was located near the city centre, and had a significantly higher population living nearby than Fulfordgate.[102]

Bootham Crescent

[edit]

Bootham Crescent was renovated over the summer of 1932; the Main and Popular Stands were built and terraces were banked up behind the goals.[100] The ground was officially opened on 31 August 1932, for York's 2–2 draw with Stockport County in the Third Division North.[103] It was played before 8,106 supporters, and York's Tom Mitchell scored the first goal at the ground.[104] There were teething problems in Bootham Crescent's early years: attendances were not higher than at Fulfordgate in its first four seasons, and there were questions over the quality of the pitch.[105] In March 1938 the ground's record attendance was set when 28,123 people watched York play Huddersfield Town in the FA Cup.[103] The ground endured slight damage during the Second World War, when bombs were dropped on houses along the Shipton Street End.[103] Improvements were made shortly after the war ended, including the concreting of the banking at the Grosvenor Road End being completed.[106]

With the club's finances in a strong position, York purchased Bootham Crescent for £4,075 in September 1948.[106] Over the late 1940s and early 1950s, concreting was completed on the terracing in the Popular Stand and the Shipton Street End.[106] The Main Stand was extended towards Shipton Street over the summer of 1955, and a year later a concrete wall was built at the Grosvenor Road End, as a safety precaution and as a support for additional banking and terracing.[107] The ground was fitted with floodlights in 1959, which were officially switched on for a friendly against Newcastle United.[108] The floodlights were updated and improved in 1980, and were officially switched on for a friendly with Grimsby Town.[109] A gymnasium was built at the Grosvenor Road End in 1981, and two years later new offices for the manager, secretary, matchday and lottery manager were built, along with a vice-presidents' lounge.[109]

During the early 1980s, the rear of the Grosvenor Road End was cordoned off as cracks had appeared in the rear wall, and this section of the ground was later segregated and allocated to away supporters.[109] Extensive improvements were made over the mid 1980s, including new turnstiles, refurbished dressing rooms, new referees' changing room and physiotherapist's treatment room being readied, hospitality boxes being built to the Main Stand and crash barriers being strengthened.[109] The David Longhurst Stand was constructed over the summer of 1991, and was named after the York player who collapsed and died from heart failure in a match a year earlier.[110][111] It provided covered accommodation for supporters in what was previously the Shipton Street End, and was officially opened for a friendly match against Leeds United.[110] In June 1995, new floodlights were installed, which were twice as powerful as the original floodlights.[110][112]

In July 1999, York ceased ownership of Bootham Crescent when their real property assets were transferred to a holding company called Bootham Crescent Holdings.[113][114] Craig announced the ground would close by 30 June 2002,[115] and under Batchelor York's lease was replaced with one expiring in June 2003.[116] In March 2003, York extended the lease to May 2004, and proceeded with plans to move to Huntington Stadium under the ownership of the Supporters' Trust.[117][118] The club instead bought Bootham Crescent in February 2004, using a £2 million loan from the Football Stadia Improvement Fund (FSIF).[119]

The ground was renamed KitKat Crescent in January 2005, as part of a sponsorship deal in which Nestlé made a donation to the club,[120] although the ground was still commonly referred to as Bootham Crescent.[121] The deal expired in January 2010, when Nestlé ended all their sponsorship arrangements with the club.[122] There had not been any major investment in the ground since the 1990s, and it faced problems with holes in the Main Stand roof, crumbling in the Grosvenor Road End, drainage problems and toilet conditions.[123][124]

York Community Stadium

[edit]

Per the terms of the FSIF loan, the club was required to have identified a site for a new stadium by 2007, and have detailed planning permission by 2009, to avoid financial penalties.[125] York failed to formally identify a site by the end of 2007,[126] and by March 2008 plans had ground to a halt.[127] In May 2008, City of York Council announced its commitment to building a community stadium,[128] for use by York and the city's rugby league club, York City Knights.[129] In July 2010, the option of building an all-seater stadium at Monks Cross in Huntington, on the site of Huntington Stadium, was chosen by the council.[130][131] In August 2014, the council named GLL as the preferred bidder to deliver an 8,000 all-seater stadium, a leisure complex and a community hub.[132] Construction started in December 2017,[133] and after a number of delays, was completed in December 2020.[134] The club officially moved into the stadium in January 2021,[135] with the first match being a 3–1 defeat to AFC Fylde on 16 February,[136] which was played behind closed doors because of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United Kingdom.[137] The stadium holds an all-seated capacity of 8,500.[138]

Supporters and rivalries

[edit]

The club has a number of domestic supporters' groups, including the East Riding Minstermen, Harrogate Minstermen, York Minstermen, York City South and the Supporters' Trust.[139][140] The now-disbanded group Jorvik Reds,[141] who were primarily inspired by the continental ultras movement,[142] were known for staging pre-match displays.[143] The York Nomad Society is the hooligan firm associated with the club.[144]

For home matches, the club produces a 60-page official match programme, entitled The Citizen.[145] York have been the subject of a number of independent supporters' fanzines, including Terrace Talk, In The City, New Frontiers, Johnny Ward's Eyes, Ginner's Left Foot, RaBTaT and Y Front.[146] The club mascot is a lion named Yorkie the Lion and he is known for performing comic antics before matches.[147] John Sentamu, the Archbishop of York, became the club patron for 2007–08, having become a regular spectator at home matches as a season ticket holder.[148]

The 2003 Football Fans Census revealed that no other team's supporters considered York to be among their club's main rivals.[149] Traditionally, York's two main rivalries have been with Hull City and Scarborough.[149] While York fans saw Hull as their main rival, this was not reciprocated by the East Yorkshire club, who saw Leeds United as their main rival.[149] York also had a rivalry with Halifax Town and they were the team most local to York when the two played in the Conference.[150] A rivalry with Luton Town developed during the club's final years in the Conference as both clubs met regularly in crucial matches, accompanied by a series of incidents involving crowd trouble, contentious transfers, and complaints about the behaviour of directors.[151][152][153][154]

Records and statistics

[edit]

The record for the most appearances for York is held by Barry Jackson, who played 539 matches in all competitions.[155] Jackson also holds the record for the most league appearances for the club, with 428.[155] Norman Wilkinson is the club's top goalscorer with 143 goals in all competitions, which includes 127 in the league and 16 in the FA Cup.[155] Six players, Keith Walwyn, Billy Fenton, Alf Patrick, Paul Aimson, Arthur Bottom and Tom Fenoughty, have also scored more than 100 goals for the club.[155]

The first player to be capped at international level while playing for York was Eamon Dunphy, when he made his debut for the Republic of Ireland against Spain on 10 November 1965.[156] The most capped player is Peter Scott, who earned seven caps for Northern Ireland while at the club.[156] The first York player to score in an international match was Anthony Straker, who scored for Grenada against Haiti on 4 September 2015.[156][157]

York's largest victory was a 9–1 win over Southport in the Third Division North in 1957,[158] while the heaviest loss was 12–0 to Chester City in 1936 in the same division.[159] Their widest victory margin in the FA Cup is by six goals, which was achieved five times.[160] These were 7–1 wins over Horsforth in 1924, Stockton Malleable in 1927 and Stockton in 1928, and 6–0 wins over South Shields in 1968 and Rushall Olympic in 2007.[160] York's record defeat in the FA Cup was 7–0 to Liverpool in 1985.[161]

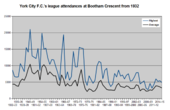

The club's highest attendance at their former Fulfordgate ground was 12,721 against Sheffield United in the FA Cup on 14 January 1931,[162] while the lowest was 1,500 against Maltby Main on 23 September 1925 in the same competition.[163] Their highest attendance at Bootham Crescent was 28,123, for an FA Cup match against Huddersfield Town on 5 March 1938;[11] the lowest was 608 against Mansfield Town in the Conference League Cup on 4 November 2008.[164][165]

The highest transfer fee received for a York player is £950,000 from Sheffield Wednesday for Richard Cresswell on 25 March 1999,[166][167] while the most expensive player bought is Adrian Randall, who cost £140,000 from Burnley on 28 December 1995.[168][169] The youngest player to play for the club is Reg Stockill, who was aged 15 years and 281 days on his debut against Wigan Borough in the Third Division North on 29 August 1929.[170] The oldest player is Paul Musselwhite, who played his last match aged 43 years and 127 days against Forest Green Rovers in the Conference on 28 April 2012.[171][172]

Players

[edit]First-team squad

[edit]

Note: Flags indicate national team as defined under FIFA eligibility rules. Players may hold more than one non-FIFA nationality. Squad correct as of 19 November 2024.[174]

| No.[a] | Pos. | Player | Nation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | GK | Harrison Male | |

| 2 | DF | Ryan Fallowfield (vice-captain)[175] | |

| 3 | DF | Adam Crookes | |

| 4 | DF | Darragh O'Connor | |

| 5 | DF | Callum Howe | |

| 6 | MF | Paddy McLaughlin | |

| 7 | FW | Tyrese Sinclair | |

| 8 | MF | Alex Hunt | |

| 9 | FW | Dipo Akinyemi | |

| 10 | FW | Ollie Pearce | |

| 11 | FW | Ashley Nathaniel-George | |

| 13 | GK | George Sykes-Kenworthy | |

| 14 | FW | Lenell John-Lewis (club captain)[175] | |

| 15 | MF | Marvin Armstrong | |

| 16 | GK | Rory Watson | |

| 17 | FW | Callum Harriott | |

| 18 | MF | Dan Batty | |

| 20 | MF | Ricky Aguiar | |

| 21 | DF | Cameron John | |

| 23 | DF | Joe Felix | |

| 25 | FW | Mo Fadera | |

| 27 | FW | Alex Hernandez | |

| 28 | DF | Malachi Fagan-Walcott (on loan from Cardiff City until end of 2024–25 season)[176] | |

| 29 | FW | Luca Thomas (on loan from Leeds United until 2 January 2025)[177] | |

| 30 | FW | David Ajiboye (on loan from Peterborough United until January 2025)[178] | |

| 31 | DF | Jeff King | |

| — | MF | Zanda Siziba |

| No.[a] | Pos. | Player | Nation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | FW | Leone Gravata (at Chippenham Town until January 2025)[179] | |

| 19 | FW | Billy Chadwick (at Boston United until December 2024)[180] | |

| 22 | DF | Levi Andoh (at Truro City until 2 January 2025)[181] | |

| 24 | MF | Bill Marshall (at Morpeth Town until December 2024)[182] | |

| 26 | DF | Leon Gibson-Booth (at Morpeth Town until December 2024)[182] | |

| — | DF | Tyler Cordner (at Ebbsfleet United until end of 2024–25 season)[183] | |

| — | MF | Olly Dyson (at Spennymoor Town until 1 January 2025)[184] | |

| — | MF | Maziar Kouhyar (at Kidderminster Harriers until end of 2024–25 season)[185] | |

| — | DF | Thierry Latty-Fairweather (at Maidenhead United until January 2025)[186] |

Former players

[edit]Clubmen of the Year

[edit]Club officials

[edit]Ownership

- As of 7 September 2024[187]

- 394 Sports (51%)

- York City Supporters' Society (25%)

- FB Sports (24%)

Board

- As of 1 February 2024[187]

- Co-chairs: Julie-Anne Uggla • Matthew Uggla

- Chief executive: Alastair Smith

- Director: James Daniels • Simon Young

Management and backroom staff

- As of 22 April 2024[188]

- Manager: Adam Hinshelwood

- Assistant manager: Gary Elphick

- First-team coaches: Tony McMahon • Cameron Morrison

- Sports scientist: Paul Harmston

- Goalkeeping coach: Joe Stead

- Kit & equipment manager: Andrew Turnbull

Former managers

[edit]Honours

[edit]York City's honours include the following:[3]

League

- Third Division (level 3)

- Promoted: 1973–74

- Fourth Division / Third Division (level 4)

- Conference Premier (level 5)

- Play-off winners: 2012

- National League North (level 6)

- Play-off winners: 2022

Cup

References

[edit]Infobox kits

- For home colours: Ramsey, Gabriel (11 June 2024). "Hummel reveal York City's 2024/25 home shirt". The Press. York. Retrieved 10 August 2024.

- For away colours: Kennedy, Emma (26 July 2024). "York City unveil 'coconut milk' away kit for 2024–25 season". The Press. York. Retrieved 10 August 2024.

- For third colours: "Adult Replica Third Shirt". York City F.C. Retrieved 10 August 2024.

Specific

- ^ Batters, David (2008). York City: The Complete Record. Derby: Breedon Books. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-85983-633-0.

- ^ Batters. York City: The Complete Record. p. 15.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "York City". Football Club History Database. Richard Rundle. Retrieved 11 August 2023.

- ^ Batters. York City: The Complete Record. p. 240.

- ^ Batters. York City: The Complete Record. p. 21.

- ^ "Third Division elections". Northern Daily Mail. Hartlepool. 30 May 1927. p. 3. Retrieved 26 February 2018 – via Findmypast.

- ^ "York City in Third Division". The Yorkshire Post. Leeds. 4 June 1929. p. 20. Retrieved 26 February 2018 – via Findmypast.

- ^ "Teenage kicks". York Evening Press. 15 April 2002. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ "York City 1929–1930: Table: Final table". Statto Organisation. Archived from the original on 6 November 2015.

- ^ Batters. York City: The Complete Record. p. 27.

- ^ a b Batters. York City: The Complete Record. p. 268.

- ^ Batters. York City: The Complete Record. pp. 35–36.

- ^ "Possible Yorkshire group". The Daily Mail. Hull. 27 September 1939. p. 6. Retrieved 26 February 2018 – via Findmypast.

- ^ "League football suspended". The Leeds Mercury. 4 September 1939. p. 9. Retrieved 26 February 2018 – via Findmypast.

- ^ Rollin, Jack (1985). Soccer at War: 1939–45. London: Willow Books. pp. 222–231. ISBN 978-0-00-218023-8.

- ^ "Football results". The Yorkshire Post and Leeds Mercury. 1 June 1942. p. 4. Retrieved 26 February 2018 – via Findmypast.

- ^ Batters. York City: The Complete Record. p. 46.

- ^ "York City 1949–1950: Table: Final table". Statto Organisation. Archived from the original on 1 October 2015.

- ^ a b Flett, Dave (12 March 2005). "Bottom sets record straight". Evening Press. York. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ Batters. York City: The Complete Record. p. 53.

- ^ "1957–58: Football League". Football Club History Database. Richard Rundle. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ "York City 1958–1959: Table: Final table". Statto Organisation. Archived from the original on 3 October 2015.

- ^ "York City 1959–1960: Table: Final table". Statto Organisation. Archived from the original on 19 July 2015.

- ^ "York City 1961–1962: Results". Statto Organisation. Archived from the original on 29 September 2015.

- ^ Batters. York City: The Complete Record. p. 60.

- ^ "York City 1963–1964: Table: Final table". Statto Organisation. Archived from the original on 29 September 2015.

- ^ "York City 1964–1965: Table: Final table". Statto Organisation. Archived from the original on 16 November 2015.

- ^ "York City 1965–1966: Table: Final table". Statto Organisation. Archived from the original on 19 July 2015.

- ^ Batters. York City: The Complete Record. pp. 63–65.

- ^ "York City 1970–1971: Table: Final table". Statto Organisation. Archived from the original on 30 September 2015.

- ^ "York City 1971–1972: Table: Final table". Statto Organisation. Archived from the original on 3 October 2015.

- ^ "York City 1972–1973: Table: Final table". Statto Organisation. Archived from the original on 26 September 2015.

- ^ Batters. York City: The Complete Record. p. 68.

- ^ "York City 1973–1974: Results". Statto Organisation. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015.

- ^ "York City 1973–1974: Table: Final table". Statto Organisation. Archived from the original on 2 October 2015.

- ^ Batters. York City: The Complete Record. p. 69.

- ^ "York City 1974–1975: Results". Statto Organisation. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015.

- ^ "York City 1974–1975: Table: Final table". Statto Organisation. Archived from the original on 29 September 2015.

- ^ "York City 1975–1976: Table: Final table". Statto Organisation. Archived from the original on 26 September 2015.

- ^ "York City 1976–1977: Table: Final table". Statto Organisation. Archived from the original on 2 October 2015.

- ^ Batters. York City: The Complete Record. p. 73.

- ^ "York City 1977–1978: Table: Final table". Statto Organisation. Archived from the original on 2 October 2015.

- ^ "York City 1978–1979: Table: Final table". Statto Organisation. Archived from the original on 30 September 2015.

- ^ "York City 1979–1980: Table: Final table". Statto Organisation. Archived from the original on 26 September 2015.

- ^ Batters. York City: The Complete Record. p. 75.

- ^ "York City 1980–1981: Table: Final table". Statto Organisation. Archived from the original on 24 October 2015.

- ^ Batters. York City: The Complete Record. pp. 75–76.

- ^ "York City 1983–1984: Table: Final table". Statto Organisation. Archived from the original on 2 October 2015.

- ^ "Points". The Football League. Archived from the original on 12 November 2017.

- ^ Carroll, Steve (26 January 2015). "It was 30 years ago today – York City 1–0 Arsenal ... Relive the FA Cup glory – With new video & photos". The Press. York. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ Batters. York City: The Complete Record. pp. 85–86.

- ^ "York City: Records". Statto Organisation. Archived from the original on 29 August 2016.

- ^ Carroll, Steve (5 November 2014). "6 great York City FA Cup games at Bootham Crescent – With videos". The Press. York. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ Batters. York City: The Complete Record. pp. 82, 368.

- ^ "York City 1987–1988: Table: Final table". Statto Organisation. Archived from the original on 26 September 2015.

- ^ Rollin, Jack, ed. (1993). Rothmans Football Yearbook 1993–94. London: Headline Publishing Group. p. 587. ISBN 978-0-7472-7895-5.

- ^ "York City 1993–1994: Results". Statto Organisation. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015.

- ^ "When City rocked the world". The Press. York. 24 September 2006. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ Batters. York City: The Complete Record. pp. 144–146.

- ^ "York City 1996–1997: Results". Statto Organisation. Archived from the original on 3 October 2015.

- ^ "York City 1998–1999: Table: Final table". Statto Organisation. Archived from the original on 26 September 2015.

- ^ "York City 1998–1999: Results". Statto Organisation. Archived from the original on 27 September 2015.

- ^ "Christmas crisis rocks club". York Evening Press. 21 December 2001. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ "Final whistle at Bootham Crescent". York Evening Press. 9 January 2002. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ "Saved". York Evening Press. 15 March 2002. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ "City get only 35 days to survive". York Evening Press. 18 December 2002. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ "It's your York City". York Evening Press. 27 March 2003. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ "Trust inch toward takeover". York Evening Press. 26 March 2003. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ "Batchelor unveils £1million car racing sponsorship". York Evening Press. 15 April 2003. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ "Wacky race too far". York Evening Press. 21 December 2002. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ "York City 2003–2004: Results". Statto Organisation. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015.

- ^ "York City 2003–2004: Table: Final table". Statto Organisation. Archived from the original on 11 October 2015.

- ^ "Doncaster 3, York City 1". York Evening Press. 26 April 2004. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ "McEwan may go". Evening Press. York. 13 April 2005. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ "York City 2006–2007: Results". Statto Organisation. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015.

- ^ Flett, Dave (25 April 2009). "York City clinch survival-securing win". The Press. York. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ Flett, Dave (11 May 2009). "York City 0, Stevenage Borough 2 – FA Trophy final at Wembley". The Press. York. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ Flett, Dave (17 May 2010). "York City 1, Oxford United 3: Blue Square Premier play-off final, Wembley, Sunday, May 16, 2010". The Press. York. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ Flett, Dave (14 May 2012). "Match report: Newport County 0, York City 2 – FA Trophy final". The Press. York. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ Flett, Dave (21 May 2012). "Match report: York City 2, Luton Town 1 – Play-off final". The Press. York. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ Flett, Dave (3 May 2013). "York City npower League Two season review". The Press. York. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ Flett, Dave (17 May 2014). "York City miss out on Wembley as brave promotion bid ends with 0–0 draw at Fleetwood". The Press. York. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ Flett, Dave (7 May 2016). "York City end four-year stint back in Football League with 1–1 draw at Morecambe". The Press. York. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ "York City 2015–2016: Table: Final table". Statto Organisation. Archived from the original on 29 August 2016.

- ^ Flett, Dave (29 April 2017). "York City relegated to National League North after 2–2 draw with Forest Green and stoppage-time goal for Guiseley". The Press. York. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ Flett, Dave (21 May 2017). "York City lift FA Trophy to win at Wembley for a fourth time in their history". The Press. York. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ a b Kilbride, Jacob (21 May 2022). "York City secure promotion with 2–0 play-off final win". The Press. York. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ Kilbride, Jacob (5 July 2022). "Jason McGill sells York City stake to Supporters' Trust". The Press. York. Retrieved 6 July 2022.

O'Reilly, James (5 July 2022). "'Deep affection' for York City from new chairman". The Press. York. Retrieved 6 July 2022. - ^ a b c d e "York City". The Beautiful History. Han van Eijden. 9 June 2011. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- ^ "To bet or not ot [sic] bet". York Evening Press. 26 August 2000. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ Ponting, Ivan (25 April 2012). "Arthur Bottom: Striker who helped Newcastle stay in the top flight". The Independent. London. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r "York City". Historical Football Kits. Dave Moor. Retrieved 8 July 2023.

- ^ Flett, Dave (18 July 2008). "Viva Minstermen". The Press. York. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ "Blue (and maroon) is the colour!". The Press. York. 1 August 2007. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ Flett, Dave (28 March 2009). "Kit's that Wembley way". The Press. York. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ a b "Lions' pride". York Evening Press. 1 May 2003. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ For Hummel as kit supplier: Ramsey, Gabriel (23 May 2024). "Hummel set to produce York City's kits in three-year deal". The Press. York. Retrieved 10 August 2024.

For Titan Wealth Holdings as shirt sponsor: Ramsey, Gabriel (8 July 2023). "York City reveal kits for 2023/24 National League season". The Press. York. Retrieved 8 July 2023. - ^ a b c Batters. York City: The Complete Record. p. 108.

- ^ Batters. York City: The Complete Record. p. 16.

- ^ a b Inglis, Simon (1996). Football Grounds of Britain (3rd ed.). London: Collins Willow. p. 420. ISBN 978-0-00-218426-7.

- ^ Batters. York City: The Complete Record. pp. 109–110.

- ^ Batters. York City: The Complete Record. p. 109.

- ^ a b c Batters. York City: The Complete Record. p. 111.

- ^ Batters. York City: The Complete Record. p. 258.

- ^ Inglis. Football Grounds of Britain. p. 421.

- ^ a b c Batters. York City: The Complete Record. p. 112.

- ^ Batters. York City: The Complete Record. pp. 112–113.

- ^ Batters. York City: The Complete Record. p. 114.

- ^ a b c d Batters. York City: The Complete Record. p. 115.

- ^ a b c Batters. York City: The Complete Record. p. 116.

- ^ Cross, Elinor (21 March 2012). "Father of pitch collapse player David Longhurst calls for screening". BBC News. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- ^ "It happened this day". York City South. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- ^ Conn, David (18 January 2002). "Chairman's threat leaves the future of York in doubt". The Independent. London. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ Batters. York City: The Complete Record. p. 94.

- ^ "Full text of document from York City". York Evening Press. 9 January 2002. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ "The fight goes on". York Evening Press. 24 February 2003. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ "Home from home". York Evening Press. 12 March 2003. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ Batters. York City: The Complete Record. pp. 99, 101.

- ^ Batters. York City: The Complete Record. pp. 101–102.

- ^ "Sweet break for York FC". Evening Press. York. 19 January 2005. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ Croll, Stuart (3 September 2007). "Ground of the week: Kit Kat Crescent!". BBC London. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- ^ Carroll, Steve (6 August 2009). "York City's sponsorship tie-up with Nestlé to comes [sic] to an end". The Press. York. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ "Sophie Hicks". York City South. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- ^ "Nick Bassett". York City South. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- ^ Batters. York City: The Complete Record. p. 102.

- ^ Flett, Dave (13 December 2007). "Santa Clause to City rescue". The Press. York. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ Flett, Dave (27 March 2008). "McGill: Club being used as a "political football"". The Press. York. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ "City stadium decision secures 'bright future' for Minstermen". The Press. York. 23 May 2008. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ Aitchison, Gavin (9 July 2008). "Council to lend York City £2.1m". The Press. York. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ Stead, Mark (26 June 2010). "York City set sights on Monks Cross stadium move". The Press. York. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ Stead, Mark (7 July 2010). "Monks Cross named as preferred site for York's community stadium". The Press. York. Archived from the original on 16 August 2015.

- ^ "Winning bid announced for community stadium". York City F.C. 26 August 2014. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ^ Turnbull, Catherine (5 December 2017). "Diggers are finally on site as work starts on new Community Stadium". The Press. York. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- ^ Laversuch, Chloe (16 December 2020). "York Community Stadium finally complete". The Press. York. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- ^ Kilbride, Jacob (8 January 2021). "York City set date for first game at LNER Community Stadium". The Press. York. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- ^ Richardson, Joe (16 February 2021). "No fairytale start for York City at the Community Stadium as Fylde win 3–1". The Press. York. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- ^ Richardson, Joe (16 February 2021). "York City chairman Jason McGill "thrilled" ahead of first match at Community Stadium". The Press. York. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- ^ "LNER Community Stadium". Better. Greenwich Leisure Limited. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ "Supporter groups". York City F.C. Archived from the original on 1 November 2012.

- ^ "York City vs Northampton Town 3rd August 2013". East Riding Minstermen. 25 July 2013. Archived from the original on 21 May 2014.

- ^ Flett, Dave (28 January 2012). "Supporters come together in Darlington's hour of need". The Press. York. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ Flett, Dave (25 October 2008). "Fans' show of strength as rift puts City into a flag daze". The Press. York. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ Carroll, Steve (29 April 2010). "Fans hoping for absolute streamer". The Press. York. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ "Lid lifted on city's hooligan culture". The Press. York. 22 June 2006. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ "The Citizen returns with added value". York City F.C. 11 August 2015. Archived from the original on 28 May 2017.

- ^ "City related books". York City South. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- ^ "Yorkie barred by Bees' big freeze". York Evening Press. 13 January 2001. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ Carroll, Steve (3 July 2007). "'U's swoop for ex-City ace Mark". The Press. York. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ a b c "Rivalry uncovered!" (PDF). Football Fans Census. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 October 2013.

- ^ "York City". Blue Square Premier Ground Guide. Duncan Adams. Archived from the original on 18 May 2008.

- ^ "Town's rivalry with York intensifies". Luton Today. 21 April 2011. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ "Press journalist Dave Flett beats ban at Kenilworth Road". The Press. York. 19 January 2011. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ "Luton may plan appeal over York split gate decision". Bedfordshire on Sunday. Bedford. 16 January 2011. Archived from the original on 7 September 2015.

- ^ Flett, Dave (28 February 2012). "York City relishing prospect of FA Trophy ties against Luton Town". The Press. York. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ a b c d Batters. York City: The Complete Record. p. 426.

- ^ a b c Batters. York City: The Complete Record. p. 428.

- ^ "Grenada vs. Haiti 1–3: Summary". Soccerway. Perform Group. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ Batters. York City: The Complete Record. p. 306.

- ^ Batters. York City: The Complete Record. p. 264.

- ^ a b Batters. York City: The Complete Record. pp. 242–424.

- ^ Batters. York City: The Complete Record. p. 362.

- ^ Batters. York City: The Complete Record. p. 254.

- ^ Batters. York City: The Complete Record. pp. 240–256.

- ^ Flett, Dave (14 May 2009). "York City season review 2008/9". The Press. York. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ Flett, Dave (5 November 2008). "Setanta Shield: York City 1, Mansfield Town 1 (4–2 on pens)". The Press. York. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ Batters. York City: The Complete Record. p. 163.

- ^ "Richard Cresswell". Soccerbase. Centurycomm. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- ^ Jarred, Martin; Windross, Dave (1997). Citizens and Minstermen: A Who's Who of York City FC 1922–1997. Selby: Citizen Publications. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-9531005-0-7.

- ^ "Adrian Randall". Soccerbase. Centurycomm. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- ^ Batters. York City: The Complete Record. p. 252.

- ^ Flett, Dave (18 April 2012). "Veteran Paul Musselwhite keeps clean sheet in key York City win". The Press. York. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ^ "Games played by Paul Musselwhite in 2011/2012". Soccerbase. Centurycomm. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- ^ Flett, Dave (21 May 2012). "Match report: York City 2, Luton Town 1 – play-off final". The Press. York. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ "Men's First Team". York City F.C. Retrieved 21 November 2024.

For 2024–25 squad numbers: "Squads – English National League 2024/2025: York City". FootballSquads. Retrieved 21 November 2024.

For Callum Harriott nationality: "C. Harriott: Summary". Soccerway. Perform Group. Retrieved 2 January 2024.

For Luca Thomas nationality: "L. Thomas: Summary". Soccerway. Perform Group. Retrieved 19 October 2024.

For David Ajiboye nationality: "D. Ajiboye: Summary". Soccerway. Perform Group. Retrieved 9 November 2024.

For Jeff King nationality: "J. King: Summary". Soccerway. Perform Group. Retrieved 15 November 2024.

For Tyler Cordner position and nationality: "T. Cordner: Summary". Soccerway. Perform Group. Retrieved 12 August 2024.

For Olly Dyson position and nationality: "O. Dyson: Summary". Soccerway. Perform Group. Retrieved 12 August 2024.

For Maziar Kouhyar position and nationality: "Maziar Kouhyar: Summary". Soccerway. Perform Group. Retrieved 12 August 2024. - ^ a b Ramsey, Gabriel (15 September 2023). "Lenell John-Lewis to remain as York City captain under Neal Ardley". The Press. York. Retrieved 2 January 2024.

- ^ Connell, Kai (2 September 2024). "York City sign defender Malachi Fagan-Walcott on season-long loan". York City F.C. Retrieved 2 September 2024.

- ^ "Luca Thomas loan deal extended until January". York City F.C. 19 November 2024. Retrieved 21 November 2024.

- ^ "York City secure speedy winger David Ajiboye on loan from League One's Peterborough United". York City F.C. 7 November 2024. Retrieved 9 November 2024.

- ^ "Leone Gravata joins Chippenham Town on loan". York City F.C. 22 September 2024. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- ^ Brookes, Ryan (8 November 2024). "Billy Chadwick joins Boston United on short-term loan". York City F.C. Retrieved 9 November 2024.

- ^ Connell, Kai (15 November 2024). "Levi Andoh joins Truro City on loan until January". York City F.C. Retrieved 15 November 2024.

- ^ a b Connell, Kai (15 November 2024). "Bill Marshall and Leon Gibson-Booth youth loans extended with Morpeth Town". York City F.C. Retrieved 15 November 2024.

- ^ Connell, Kai (21 June 2024). "Tyler Cordner joins Ebbsfleet United on season-long loan". York City F.C. Retrieved 12 August 2024.

- ^ Connell, Kai (29 July 2024). "Olly Dyson joins Spennymoor Town on loan". York City F.C. Retrieved 12 August 2024.

- ^ Connell, Kai (16 July 2024). "Maz Kouhyar joins Kidderminster Harriers on season-long loan". York City F.C. Retrieved 12 August 2024.

- ^ Connell, Kai (7 October 2024). "Thierry Latty-Fairweather re-joins Maidenhead United on loan". York City F.C. Retrieved 7 October 2024.

- ^ a b "Ownership & Board". York City F.C. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- ^ "Men's First Team". York City F.C. Retrieved 28 April 2024.

For David Stockdale departure: Connell, Kai (22 April 2024). "Club Statement: David Stockdale and Matthew Lever depart". York City F.C. Retrieved 22 April 2024.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- York City F.C. on BBC Sport: Club news – Recent results and fixtures