World music

| World music | |

|---|---|

| Cultural origins | Indigenous music worldwide |

| Derivative forms | Folktronica |

| Subgenres | |

| |

| Fusion genres | |

| Regional scenes | |

| World music (term) | |

|---|---|

| Etymology | Coined early 1960s to describe non-European, non-North American music[1] |

"World music" is an English phrase for styles of music from non-English speaking countries, including quasi-traditional, intercultural, and traditional music. World music's broad nature and elasticity as a musical category pose obstacles to a universal definition, but its ethic of interest in the culturally exotic is encapsulated in Roots magazine's description of the genre as "local music from out there".[1][2]

Music that does not follow "North American or British pop and folk traditions"[3] was given the term "world music" by music industries in Europe and North America.[4] The term was popularized in the 1980s as a marketing category for non-Western traditional music.[5][6] It has grown to include subgenres such as ethnic fusion (Clannad, Ry Cooder, Enya, etc.)[7] and worldbeat.[8][9]

Lexicology

[edit]

The term "world music" has been credited to ethnomusicologist Robert E. Brown, who coined it in the early 1960s at Wesleyan University in Connecticut, where he developed undergraduate through doctoral programs in the discipline. To enhance the learning process (John Hill), he invited more than a dozen visiting performers from Africa and Asia and began a world music concert series.[10][11] The term became current in the 1980s as a marketing/classificatory device in the media and the music industry.[12] There are several conflicting definitions for world music. One is that it consists of "all the music in the world", though such a broad definition renders the term virtually meaningless.[13][14]

Forms

[edit]

Examples of popular forms of world music include the various forms of non-European classical music (e.g. Chinese guzheng music, Indian raga music, Tibetan chants), Eastern European folk music (e.g. the village music of the Balkans, The Mystery of the Bulgarian Voices), Nordic folk music, Latin music, Indonesian music, and the many forms of folk and tribal music of the Middle East, Africa, Asia, Oceania, Central and South America.

The broad category of world music includes isolated forms of ethnic music from diverse geographical regions. These dissimilar strains of ethnic music are commonly categorized together by virtue of their indigenous roots. Over the 20th century, the invention of sound recording, low-cost international air travel, and common access to global communication among artists and the general public have given rise to a related phenomenon called "crossover" music. Musicians from diverse cultures and locations could readily access recorded music from around the world, see and hear visiting musicians from other cultures and visit other countries to play their own music, creating a melting pot of stylistic influences. While communication technology allows greater access to obscure forms of music, the pressures of commercialization also present the risk of increasing musical homogeneity, the blurring of regional identities, and the gradual extinction of traditional local music-making practices.[15]

Hybrid examples

[edit]

Since the music industry established this term, the fuller scope of what an average music consumer defines as "world" music in today's market has grown to include various blends of ethnic music tradition, style and interpretation,[9] and derivative world music genres have been coined to represent these hybrids, such as ethnic fusion and worldbeat. Good examples of hybrid, world fusion are the Irish-West African meld of Afro Celt Sound System,[16] the pan-cultural sound of AO Music[17] and the jazz / Finnish folk music of Värttinä,[18] each of which bear tinges of contemporary, Western influence—an increasingly noticeable element in the expansion genres of world music. Worldbeat and ethnic fusion can also blend specific indigenous sounds with more blatant elements of Western pop. Good examples are Paul Simon's album Graceland, on which South African mbaqanga music is heard; Peter Gabriel's work with Pakistani Sufi singer Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan; the Deep Forest project, in which vocal loops from West Africa are blended with Western, contemporary rhythmic textures and harmony structure; and the work of Mango, who combined pop and rock music with world elements.

Depending on style and context, world music can sometimes share the new-age music genre, a category that often includes ambient music and textural expressions from indigenous roots sources. Good examples are Tibetan bowls, Tuvan throat singing, Gregorian chant or Native American flute music. World music blended with new-age music is a sound loosely classified as the hybrid genre 'ethnic fusion'. Examples of ethnic fusion are Nicholas Gunn's "Face-to-Face" from Beyond Grand Canyon, featuring authentic Native American flute combined with synthesizers, and "Four Worlds" from The Music of the Grand Canyon, featuring spoken word from Razor Saltboy of the Navajo Indian Nation.

World fusion

[edit]The subgenre world fusion is often mistakenly assumed to refer exclusively to a blending of Western jazz fusion elements with world music. Although such a hybrid expression falls easily into the world fusion category, the suffix "fusion" in the term world fusion should not be assumed to mean jazz fusion. Western jazz combined with strong elements of world music is more accurately termed world fusion jazz,[19] ethnic jazz or non-Western jazz. World fusion and global fusion are nearly synonymous with the genre term worldbeat, and though these are considered subgenres of popular music, they may also imply universal expressions of the more general term world music.[9] In the 1970s and 1980s, fusion in the jazz music genre implied a blending of jazz and rock music, which is where the misleading assumption is rooted.[20]

Precursors

[edit]Millie Small released "My Boy Lollipop" in 1964. Small's version was a hit, reaching number 2 both in the UK Singles Chart[21] and in the US Billboard Hot 100. In the 1960s, Miriam Makeba and Hugh Masekela had popular hits in the USA. In 1969 Indian musician Ravi Shankar played sitar at the Woodstock festival.[22]

In the 1970s, Manu Dibango's funky track "Soul Makossa"[23] (1972) became a hit, and Osibisa released "Sunshine Day" (1976). Fela Kuti created Afrobeat[24] and Femi Kuti, Seun Kuti and Tony Allen followed Fela Kuti's funky music. Salsa musicians such as José Alberto "El Canario", Ray Sepúlveda, Johnny Pacheco, Fania All-Stars, Ray Barretto, Rubén Blades, Gilberto Santa Rosa, Roberto Roena, Bobby Valentín, Eddie Palmieri, Héctor Lavoe and Willie Colón developed Latin music.[25]

The 1979 American ensemble Libana was incorporated by founder Susan Robbins, specifically to represent world folk traditions through chants, dance, storytelling, and musical performance. Initially consisting of 25 women, it honed down to 6 "core" members who able to travel the world, all of whom toured in America, Canada, Bulgaria, India, Greece, and Morrocco.[26] Libana has performed music of divergent cultural expressions, of the Mediterranean, the Balkans, the Middle East, Europe, Africa, Asia and South America.[27] Libana musicians use instruments such as guitars, hammered dulcimers, ouds, bağlamas, pan flutes, charangos, djembes, davuls, frame drums,[28] double bass, clarinets, dumbeks, accordions, and naqarehs.[27] They continue to be active as of 2024.

The Breton musician Alan Stivell pioneered the connection between traditional folk music, modern rock music and world music with his 1972 album Renaissance of the Celtic Harp.[29] Around the same time, Stivell's contemporary, Welsh singer-songwriter Meic Stevens popularised Welsh folk music.[30] Neo-traditional Welsh language music featuring a fusion of modern instruments and traditional instruments such as the pibgorn and the Welsh harp has been further developed by Bob Delyn a'r Ebillion. Lebanese musical pioneer Lydia Canaan fused Middle-Eastern quarter notes and microtones with anglophone folk, and is listed in the catalog of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum's Library and Archives[31][32] as the first rock star of the Middle East.[32][33][34][35][36]

Popular genres

[edit]Although it primarily describes traditional music, the world music category also includes popular music from non-Western urban communities (e.g. South African "township" music) and non-European music forms that have been influenced by other so-called third-world musics (e.g. Afro-Cuban music).[37]

The inspiration of Zimbabwe's Thomas Mapfumo in blending the Mbira (finger Piano) style onto the electric guitar, saw a host of other Zimbabwean musicians refining the genre, none more successfully than The Bhundu Boys. The Bhundu Jit music hit Europe with some force in 1986, taking Andy Kershaw and John Peel fully under its spell.

For many years, Paris has attracted numerous musicians from former colonies in West and North Africa. This scene is aided by the fact that there are many concerts and institutions that help to promote the music.

Algerian and Moroccan music have an important presence in the French capital. Hundreds of thousands of Algerian and Moroccan immigrants have settled in Paris, bringing the sounds of Amazigh (Berber), raï, and Gnawa music.

The West African music community is also very large, integrated by people from Senegal, Mali, Ivory Coast, and Guinea.

Unlike musical styles from other regions of the globe, the American music industry tends to categorize Latin music as its own genre and defines it as any music from Spanish- and Portuguese- speaking countries.[38]

Western

[edit]The most common name for this form of music is also "folk music", but is often called "contemporary folk music" or "folk revival music" to make the distinction.[39] The transition was somewhat centered in the US and is also called the American folk music revival.[40] Fusion genres such as folk rock and others also evolved within this phenomenon.

1987 industry meeting

[edit]

On 29 June 1987, a meeting of interested parties gathered to capitalize on the marketing of non-Western folk music. Paul Simon had released the world music-influenced album Graceland in 1986.[41] The concept behind the album had been to express his own sensibilities using the sounds he had fallen in love with while listening to artists from Southern Africa, including Ladysmith Black Mambazo and Savuka. This project and the work of Peter Gabriel and Johnny Clegg among others had, to some degree, introduced non-Western music to a wider audience. They saw this as an opportunity.

In an unprecedented move, all of the world music labels coordinated together and developed a compilation cassette for the cover of the music magazine NME. The overall running time was 90 minutes, each package containing a mini-catalog showing the other releases on offer.

By the time of a second meeting it became clear that a successful campaign required its own dedicated press officer. The press officer would be able to juggle various deadlines and sell the music as a concept—not just to national stations, but also regional DJs keen to expand their musical variety. DJs were a key resource as it was important to make "world music" important to people outside London—most regions after all had a similarly heritage to tap into. A cost-effective way of achieving all this would be a leafleting campaign.

The next step was to develop a world music chart, gathering together selling information from around fifty shops, so that it would finally be possible to see which were big sellers in the genre—so new listeners could see what was particularly popular. It was agreed that the NME could again be involved in printing the chart and also Music Week and the London listings magazine City Limits. It was also suggested that Andy Kershaw might be persuaded to do a run down of this chart on his show regularly.

Relationship to immigration and multiculturalism

[edit]This section is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. (September 2021) |

In most wealthy industrialized countries, large amounts of immigration from other regions has been ongoing for many decades. This has introduced non-Western music to Western audiences not only as "exotic" imports, but also as local music played by fellow citizens. But the process is ongoing and continues to produce new forms. In the 2010s several musicians from immigrant communities in the West rose to global popularity, such as Haitian-American Wyclef Jean, Somali-Canadian K'naan, Tamil-Briton M.I.A., often blending the music of their heritage with hip-hop or pop. Cuban-born singer-songwriter Addys Mercedes started her international career from Germany mixing traditional elements of Son with pop.[42]

Once, an established Western artist might collaborate with an established African artist to produce an album or two. Now, new bands and new genres are built from the ground up by young performers. For example, the Punjabi-Irish fusion band Delhi 2 Dublin is from neither India nor Ireland, but Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. Country for Syria, an Istanbul based music collective, blends American country music with the music of Syrian refugees and local Turkish music.[43] Musicians and composers also work collectively to create original compositions for various combinations of western and non western instruments.

The introduction of non-western music into western culture created a fusion that influenced both parties. (Feld 31)[44] With the quick demand for new music came the technicalities of ownership. As Feld states in page 31:[44] "This complex traffic in sounds money and media is rooted in the nature of revitalization through appropriation." There are collaborations between African and American popular music artists that raise questions on who is benefiting from said collaborations.(Feld 31)[44] Feld mentions the example of "That was your mother". Alton Rubin and his band the Twisters collaborated with Paul Simon on the song that possessed a zydeco feel, signature of Dopsie's band. Even though Paul Simon wrote and sang the lyrics with them, the whole copyright is attributed to Paul and not to the band as well. (Feld 34) [44] Because of crossovers like this one, where there was a disproportional gain when covering non-western music. Feld states that

"...international music scene, where worldwide media contact, amalgamation of the music industry towards world record sales domination by three enormous companies, and extensive copyright controls by a few Western countries are having a riveting effect on the commodification of musical skill and styles, and on the power of musical ownership." (Feld 32)[44]

Immigration also heavily influences world music, providing a variety of options for the wider public. In the 1970s Punjabi music was greatly popular in the UK because of its growing Punjabi diaspora. (Schreffler 347)[45] Bhangra music was also greatly covered by its diaspora in cities like New York and Chicago. (Schreffler 351)[45] For a more mainstream integration, the Punjabi music scene integrated collaborations with rappers and started gaining more recognition. One of these successful attempts was a remix of the song "Mundiān ton Bach ke" called "Beware of the Boys" by Panjabi MC featuring Jay Z. (Schreffler 354)[46] Collaborations between outsider artists provided an integration of their music, even with foreign instrumentation, into the popular music scene.

Immigration, being a great part of music exportation, plays a big role in cultural identity. Immigrant communities use music to feel as if they are home and future generations it plays the role of educating or giving insight into what their culture is about. In Punjabi culture, music became the carrier of culture around the world. (Schreffler 355)[46]

Radio programs

[edit]World music radio programs today often play African hip hop or reggae artists, crossover Bhangra and Latin American jazz groups, etc. Common media for world music include public radio, webcasting, the BBC, NPR, and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. By default, non-region-specific or multi-cultural world music projects are often listed under the generic category of world music.

Examples of radio shows that feature world music include The Culture Cafe on WWUH West Hartford, World of Music on Voice of America, Transpacific Sound Paradise on WFMU, The Planet on Australia's ABC Radio National, DJ Edu presenting D.N.A: DestiNation Africa on BBC Radio 1Xtra, Adil Ray on the BBC Asian Network, Andy Kershaw's show on BBC Radio 3 and Charlie Gillett's show[47] on the BBC World Service.

Awards

[edit]

The BBC Radio 3 Awards for World Music was an award given to world music artists between 2002 and 2008, sponsored by BBC Radio 3. The award was thought up by fRoots magazine's editor Ian Anderson, inspired by the BBC Radio 2 Folk Awards. Award categories included: Africa, Asia/Pacific, Americas, Europe, Mid East and North Africa, Newcomer, Culture Crossing, Club Global, Album of the Year, and Audience Award. Initial lists of nominees in each category were selected annually by a panel of several thousand industry experts. Shortlisted nominees were voted on by a twelve-member jury, which selected the winners in every category except for the Audience Award category. These jury members were appointed and presided over by the BBC.[48] The annual awards ceremony was held at the BBC Proms and winners were given an award called a "Planet". In March 2009, the BBC made a decision to axe the BBC Radio 3 Awards for World Music.[49][50]

In response to the BBC's decision to end its awards program, the British world music magazine Songlines launched the Songlines Music Awards in 2009 "to recognise outstanding talent in world music".[51]

The WOMEX Awards were introduced in 1999 to honor the high points of world music on an international level and to acknowledge musical excellence, social importance, commercial success, political impact and lifetime achievement.[52] Every October at the WOMEX event, the award figurine—an ancient mother goddess statue dating back about 6000 years to the Neolithic age—is presented in an award ceremony to a worthy member of the world music community.

Festivals

[edit]Many festivals are identified as being "world music"; here's a small representative selection:

Australia

- The Globe to Globe World Music Festival takes place in the City of Kingston, Melbourne, for 2 days each year in January.[54]

Bangladesh

- The Dhaka World Music Festival takes place in Dhaka.

Belgium

- Sfinks Festival in Boechout, Belgium is a 4-day world music festival.

Canada

- Sunfest is an annual 4-day world music festival that happens in London, Ontario, primarily in Victoria Park; it typically runs the weekend after Canada Day in early July.

Croatia

- Ethnoambient is a two- or three-day world music festival held every summer since 1998 in Solin, Dalmatia, in southern Croatia.

France

- The Festival de l'Inde takes place in Evian, Haute-Savoie.

- In 1982, Fête de la Musique ("World Music Day") was initiated in France.[55] World Music Day has been celebrated on 21 June every year since then.

Germany

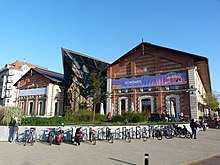

- The TFF Rudolstadt takes place annually on the first full July weekend in Rudolstadt, Thuringia, Germany.

- The German World Music Festival der Klangfreunde takes place every first weekend of August, at Schlosspark Loshausen. Klangfreunde e. V. is a non-profit organization.

- Wilde Töne, Festival für Folk- und Weltmusik in Braunschweig Germany[56]

Ghana

- SUNSET MUSIC FESTIVAL

(Free Electronic Dance Music Festival) was established in (2020) at Busua Beach in the Western Region, by Djsky S K Y M U S I C.[57]

Hungary

- WOMUFE (World Music Festival) in Budapest, Hungary (1992)

- The WOMEX when in Budapest (2015)

Iceland

- Fest Afrika Reykjavík takes place every September.

India

- Udaipur World Music Festival

- The Lakshminarayana Global Music Festival (LGMF) takes place annually during December–January, often across several major cities in India. The LGMF has also traveled to 22 countries.[58]

Indonesia

- Matasora World Music Festival is held in Bandung, West Java, and Jakarta.

- Toba Caldera World Music Festival in Lake Toba, Toba Regency, North Sumatra.

- Canang World Music Festival in Riau

Iran

- The Fajr International Music Festival is Iran's most prestigious music festival, founded in 1986. The festival is affiliated with UNESCO and includes national and international competition sections. Since its establishment, many musicians from several countries like Austria, Germany, France have participated in the event. The festival has enjoyed a strong presence of Asian countries as well.[59]

Italy

- The Ariano Folkfestival is a five-day world music festival held every summer in Ariano Irpino, a small town in southern Italy.

- The World Music Festival Lo Sguardo di Ulisse was first held in 1997 in Campania, Italy.

North Macedonia

- OFFest is a five-day world music festival held every summer since 2002 in Skopje.

Malaysia

- The Rainforest World Music Festival is an annual three-day music festival held in Kuching, Sarawak, Malaysia.

Mali

- The Festival au Désert took place every year from 2001 until 2012 in Mali, West Africa, and achieved international status in spite of the difficulties of reaching its location.[60]

Morocco

- Mawazine is a festival of world music that takes place annually in Rabat, Morocco, featuring Arab and international music icons.[61]

New Zealand

- A world music festival is held in New Plymouth, New Zealand, in early March each year, namely the New Zealand location of WOMAD.[62]

Nigeria

- World Music day is usually celebrated for one week in Lagos, Nigeria at different location around the state.[63]

Poland

- Poland's Cross-Culture Warsaw Festival is held in September each year.[64]

- Brave Festival, Wrocław, Poland. July each year.

- Ethno Port, Poznań, Poland. June each year.

- Ethno Jazz Festival in Wrocław, Poland. Several events throughout the whole year.

- Different Sounds (Inne brzmienia), Lublin, Poland. July each year.[65]

- Francophonic Festival in Warsaw, Poland. March each year.

- Nowa Tradycja (New Tradition), Warsaw, Poland. May each year.[66]

- Siesta Festival, Gdańsk, Poland. First edition in April/May 2011.

Portugal

- Festival Músicas do Mundo, Sines, Setúbal District is a world music festival first held in 1998.

Romania

- Méra World Music Festival[67] takes place annually at the end of July or the beginning of August (including the first weekend of August) in the rural farms of Méra village (Kalotaszeg Region/ Țara Călatei, Cluj County, Romania). It was held for the first time in 2016 and it is the only world music festival in Transylvania. Besides the diverse international musical program, "Méra World Music" offers a unique insight into the local traditional folk culture.

- "Plai Festival" in Timișoara

Serbia

- The Serbia World Music Festival is a three-day world music festival held every summer in Takovo, a small village in central Serbia.

Spain Spain's most important world music festivals are:

- Etnosur, in Alcalá la Real, Jaén (Andalucía region)

- Pirineos Sur, in Aragón region

- Festival Internacional de Música Popular Tradicional in Vilanova i la Geltrú / Vilanova International World Music Festival (Catalonia)

- La Mar de Músicas, in Cartagena (Murcia region)

- Fira Mediterrània, in Manresa (Catalonia)

- The WOMEX when in Seville (2003, 2006, 2007, 2008)

- Territorios, in Seville

Sweden

- The "Yoga Mela" Yoga & Sacred Music Festival is held annually in Skåne County.[68]

Tanzania

- Sauti za Busara is an all-African music festival, held every year in February in Zanzibar, Tanzania.

Turkey

- Konya Mystic Music Festival is held annually in Konya since 2004, in recent years in commemoration of Rumi's birthday. The festival features traditional music from around the world with a mystical theme, religious function or sacred content.[69]

- The Fethiye World Music Festival presents musicians from different countries of the world.[70]

Uganda

- The Milege World Music Festival has become a big festival in Uganda inviting musicians and fans from all over Africa and the rest of the world to enjoy live music, games, sports and so on. The festival runs for three consecutive days every November at the Botanical Gardens, Entebbe, Uganda.

Ukraine

- Svirzh World Music Festival (Lviv region)

United Kingdom

- Glastonbury Festival is an annual five-day festival of contemporary performing arts held in Pilton, Somerset, near Glastonbury.

- Musicport World Music Festival is held annually at The Spa Pavilion, Whitby, North Yorkshire.

- The Music Village Festival is held every two years in London and has been running since 1987. It is organised by the Cultural Co-operation.

- Drum Camp, established in 1996, is a unique world music festival, combining singing, dancing, and drumming workshops during the day with live concerts at night.[71]

- World Music Month, started in October 1987, is a music festival held at the O2 Forum Kentish Town in London; it was the start of the winter season for both WOMAD and Arts Worldwide.

- WOMAD Charlton Park has been running annually since 1986 and is held at Charlton Park in Wiltshire.

United States

- The Sierra Nevada World Music Festival is an annual music festival held every June on the weekend of or the weekend following the summer solstice. It is currently held at the Mendocino County Fairgrounds in Boonville, California.

- The Lotus World Music & Arts Festival is a four-day event held each September in Bloomington, Indiana.

- The California World Music Festival is held each July at the Nevada County Fairgrounds.

- The World Sacred Music Festival is held annually in Olympia, Washington, sponsored by Interfaith Works.

- FloydFest in Floyd, Virginia, United States, has featured artists from a wide diversity of styles.

- The Finger Lakes GrassRoots Festival of Music and Dance in Trumansburg, New York, has featured artists from a variety of world and ethnic music genres.

- Stern Grove Festival is a San Francisco celebration of musical and cultural diversity, including symphony orchestras and operatic stars.

- The Starwood Festival is a seven-day neopagan, new age, multicultural and world music festival that has been held in July every year since 1981 at various locations in the United States.[72]

- The World Music and Dance Festival is held annually each spring at the California Institute of the Arts.[73]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Chris Nickson. The NPR Curious Listener's Guide to World Music. Grand Central Press, 2004. pp. 1-2.

- ^ Blumenfeld, Hugh (2000-06-14). "Folk Music 101: Part I: What Is Folk Music – Folk Music". The Ballad Tree. Archived from the original on 2002-06-27. Retrieved 2017-02-08.

- ^ Discover music: "International" Archived 2020-09-04 at the Wayback Machine. RhythmOne. Retrieved 2020-09-04.

- ^ Byrne, David (3 October 1999). "Crossing Music's Borders in Search of Identity; 'I Hate World Music'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 15 April 2011. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- ^ Erlmann, Veit (1996). "Aesthetics of the Global Imagination: Reflections on World Music in the 1990s". Public Culture. Vol. 8, no. 3. pp. 467–488.

- ^ Frith, Simon (2000). "The Discourse of World Music". In Born and Hesmondhalgh (ed.). Western Music and Its Others: Difference, Representation, and Appropriation in Music. University of California Press.

- ^ "Ethnic fusion Music". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 2012-04-29. Retrieved 2020-04-16.

- ^ "Worldbeat". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 2012-05-03. Retrieved 2020-04-16.

- ^ a b c "World Fusion Music". Worldmusic.nationalgeographic.com. Archived from the original on 2012-03-14.

- ^ Williams, Jack. "Robert E. Brown brought world music to San Diego schools | The San Diego Union-Tribune". Signonsandiego.com. Archived from the original on 2015-10-22. Retrieved 2010-04-24.

- ^ "World Music and Ethnomusicology". Ethnomusic.ucla.edu. 1991-09-23. Archived from the original on 2013-10-02. Retrieved 2013-04-22.

- ^ "What Is World Music?". people.iup.edu. December 1994. Archived from the original on 2020-10-20. Retrieved 2014-10-27.

- ^ Bohlman, Philip (2002). World Music: A Very Short Introduction, "Preface". ISBN 0-19-285429-1.

- ^ Nidel 2004, p.3

- ^ Seeger, Anthony (December 1996). "Traditional Music in Community Life: Aspects of Performance, Recordings, and Preservation". Cultural Survival Quarterly Magazine. Archived from the original on 18 September 2019. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- ^ "Afro Celt Sound System". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 2012-05-19. Retrieved 2020-04-16.

- ^ "Aomusic". AllMusic.

- ^ "Värttinä". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 2011-12-30. Retrieved 2020-04-16.

- ^ "World Fusion". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 2012-05-02. Retrieved 2020-04-16.

- ^ "Fusion". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 2012-02-19. Retrieved 2020-04-16.

- ^ Roberts, David (2006). British Hit Singles & Albums (19th ed.). London: Guinness World Records Limited. p. 367. ISBN 1-904994-10-5.

- ^ "Ravi Shankar Live At Woodstock 1969 | The Real Woodstock Story". Archived from the original on 2021-08-12. Retrieved 2021-08-25.

- ^ "Soul Makossa - Manu Dibango | Songs, Reviews, Credits". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 2022-11-14. Retrieved 2021-08-25.

- ^ "Home". Felakuti.com. Archived from the original on 9 June 2022. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- ^ "Latin Music Genre Overview". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 2021-03-22. Retrieved 2021-08-25.

- ^ "LIBANA - About Libana". 2024-03-02. Archived from the original on March 2, 2024. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ a b "LibanaSingers.com - World Music A Cappella Group". 2024-07-07. Archived from the original on July 7, 2024. Retrieved 2024-08-09.

- ^ Roberts, Lee B. (2015-04-29). "Libana brings world music and dance to Prairie School". Journal Times. Archived from the original on August 9, 2024. Retrieved 2024-08-09.

- ^ Bruce Elder. All Music Guide, Renaissance of the Celtic harp Archived 2009-11-11 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 15 July 2009.

- ^ "3am Interview: FOLK MINORITY – AN INTERVIEW WITH MEIC STEVENS". 3ammagazine.com. Archived from the original on 2015-07-31. Retrieved 2015-09-12.

- ^ "Library and Archives Subject File (Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum Records--Curatorial Affairs Division Records) – Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum – Library and Archives – Catalog". catalog.rockhall.com. Archived from the original on 2019-03-29. Retrieved 2016-04-25.

- ^ a b O'Connor, Tom. "Lydia Canaan One Step Closer to Rock n' Roll Hall of Fame" Archived 2016-04-29 at the Wayback Machine, The Daily Star, Beirut, April 27, 2016.

- ^ Salhani, Justin. "Lydia Canaan: The Mideast’s First Rock Star" Archived 2015-05-05 at the Wayback Machine, The Daily Star, Beirut, November 17, 2014.

- ^ Livingstone, David. "A Beautiful Life; Or, How a Local Girl Ended Up With a Recording Contract in the UK and Who Has Ambitions in the U.S." Archived 2016-04-23 at the Wayback Machine, Campus, No. 8, p. 2, Beirut, February 1997.

- ^ Ajouz, Wafik. "From Broumana to the Top Ten: Lydia Canaan, Lebanon's 'Angel' on the Road to Stardom" Archived 2015-06-19 at the Wayback Machine, Cedar Wings, No. 28, p. 2, Beirut, July–August 1995.

- ^ Aschkar, Youmna. "New Hit For Lydia Canaan" Archived 2015-06-19 at the Wayback Machine, Eco News, No. 77, p. 2, Beirut, January 20, 1997.

- ^ "ADP Press - Afro-Cuban Music". African-diaspora-press.com. Archived from the original on 8 June 2022. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- ^ Abaroa, Gabriel (2019). "The First Twenty Years". 20a Entrega Anual del Latin Grammy. The Latin Recording Academy: 10. Retrieved July 20, 2022.

- ^ Ruehl, Kim. "Folk Music". About.com definition. Archived from the original on November 22, 2016. Retrieved August 18, 2011.

- ^ "Folk Music and Song: American Folklife Center: An Illustrated Guide (Library of Congress)". Loc.gov. Archived from the original on 22 October 2019. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- ^ "Graceland". Paulsimon.com. Archived from the original on 2019-05-18. Retrieved 2019-06-14.

- ^ "Addys Mercedes". Addysmercedes.com. Archived from the original on 2012-10-20. Retrieved 2015-05-18.

- ^ "American country music with an Arabic twist". DailySabah. Archived from the original on 2017-02-11. Retrieved 2017-02-09.

- ^ a b c d e Feld, Steven. 1988. “Notes on ‘World Beat’.” Public Culture Bulletin 1(1): 31-7.

- ^ a b Schreffler, Gibb. 2012. “Migration Shaping Media: Punjabi Popular Music in a Global Historical Perspective.” Popular Music and Society 35(3): 347-355.

- ^ a b Schreffler, Gibb. 2012. “Migration Shaping Media: Punjabi Popular Music in a Global Historical Perspective.” Popular Music and Society 35(3): 347-355.

- ^ "BBC World Service - Find a Programme - Charlie Gillett's World of Music". Archived from the original on 2013-12-14. Retrieved 2019-12-25.

- ^ "Radio 3—Awards for World Music 2008". BBC. Archived from the original on 2022-11-19. Retrieved 2013-04-22.

- ^ Donovan, Paul (2009-03-22). "Mystery of missing BBC music awards". The Sunday Times. London. Archived from the original on 2011-06-16. Retrieved 2009-03-21.

- ^ Dowell, Ben (2009-03-20). "BBC axes Radio 3 Awards for World Music". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2009-03-23. Retrieved 2009-03-21.

- ^ "Songlines – Music Awards – 2017 – winners". Songlines.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2015-07-04. Retrieved 2011-11-15.

- ^ "WOMEX Awards". Womex.com. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- ^ "Radio 3—WOMAD 2005". BBC. Archived from the original on 2009-01-14. Retrieved 2010-04-24.

- ^ "Kingston City Council, Melbourne, Australia—Globe to Globe World Music Festival". Kingston.vic.gov.au. 2013-01-31. Archived from the original on 2013-05-15. Retrieved 2013-04-22.

- ^ "Historique de la Fête de la musique". fetedelamusique.culture.gouv.fr. Archived from the original on 2018-02-04. Retrieved 2023-06-09.

- ^ "Initiative Folk e.V". Folk-music.de. Archived from the original on 2019-11-17. Retrieved 2010-04-24.

- ^ "Meet the incredible DJ taking EDM Music from Ghana to the World - Djsky". 22 October 2019. Archived from the original on 15 January 2021. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- ^ "LGMF". L Subramaniam Foundation. Archived from the original on 2014-03-28. Retrieved 2014-03-28.

- ^ "Fajr International Music Festival". Archived from the original on 2015-08-14. Retrieved 2015-09-09.

- ^ Festival in the Desert—Artist Detail Information Archived 2005-12-14 at the Wayback Machine; BBC Four, "Festival in the Desert 2004", 5 November 2004.

- ^ "Festival Mawazine". Festivalmawazine.ma. Archived from the original on 2012-10-28. Retrieved 2010-05-10.

- ^ "WOMAD • Taranaki". 22 September 2010. Archived from the original on 2010-09-22. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- ^ "Makemusiclagos – A Celebration Of World Music Day". Makemusiclagos.org.ng. Archived from the original on 19 May 2022. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- ^ "Stołeczna Estrada—O projekcie". Estrada.com.pl. Archived from the original on 2012-03-22. Retrieved 2013-04-22.

- ^ "Strona główna". Innebrzmienia.pl. Archived from the original on 2013-02-06. Retrieved 2013-04-22.

- ^ "Nowa Tradycja 2013—XVI Festiwal Folkowy Polskiego Radia". .polskieradio.pl. Archived from the original on 2013-04-30. Retrieved 2013-04-22.

- ^ "Méra World Music Festival". Meraworldmusic.com. Archived from the original on 2018-10-04. Retrieved 2019-09-08.

- ^ "Green World Yoga & Sacred Music Festival". Yogamela.se. Archived from the original on 2023-04-27. Retrieved 2018-03-26.

- ^ "Konya International Mystic Music Festival". Mysticmusicfest.com. Archived from the original on 2011-01-17. Retrieved 2011-01-04.

- ^ "Fethiye World Music Festival". Fethiyeworldmusicfestival.blogspot.com. 17 August 2017. Archived from the original on 16 May 2013. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- ^ "The World Music Workshop Festival 2019". Facebook.com. Retrieved 2020-08-09.

- ^ Krassner, Paul (2005). Life Among the Neopagans Archived 2012-11-27 at the Wayback Machine in The Nation, August 24, 2005. Retrieved November 28, 2012.

- ^ "CalArts World Music and Dance Festival". Eventbrite.com. Archived from the original on 2019-04-26. Retrieved 2019-04-26.

General sources

[edit]- Nidel, Richard (2004). World Music: The Basics. ISBN 0-415-96801-1.

- Bernard, Yvan, and Nathalie Fredette (2003). Guide des musiques du monde: une selection de 100 CD. Rév., Sophie Sainte-Marie. Montréal: Éditions de la Courte échelle. N.B.: Annotated discography. ISBN 2-89021-662-4

- Manuel, Peter (1988). Popular Musics of the Non-Western World: An Introductory Survey. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505342-7.

- N'Dour, Youssou. "Foreword" to Nickson, Chris (2004), The NPR Curious Listener's Guide to World Music. ISBN 0-399-53032-0.

- Sorce Keller, Marcello (1996). "Of Minority Musics, Preservation, and Multiculturalism: Some Considerations". In Ursula Hemetek and Emil H. Lubej (eds), Echo der Vielfalt: traditionelle Musik von Minderheiten/ethnischen Gruppen = Echoes of Diversity: Traditional Music of Ethnic Groups/Minorities, Schriften zur Volksmusik 16, 41–47. Vienna, Cologne, and Weimar: Böhlau Verlag. ISBN 3-205-98594-X. Reprinted in Sonus 18, no. 2 (Spring 1998): 33–41.

- Wergin, Carsten (2007). World Music: A Medium for Unity and Difference? EASA Media Anthropology Network. [1] Archived 2016-08-06 at the Wayback Machine.

- Guide To World Musics Archived 2012-08-25 at the Wayback Machine, World Music Network.

- An Introduction to Music Studies, Chapter 6: Henry Stobart, "World Musics".

Further reading

[edit]- Kroier, Johann (June 2012). "Music, Global History, and Postcoloniality". International Review of the Aesthetics and Sociology of Music. 43 (1): 139–186. JSTOR 41552766.

External links

[edit]- Music Listings Archived 2013-09-28 at the Wayback Machine—Top-ranking free world music podcasts

- List of World Music Festivals Archived 2015-12-22 at the Wayback Machine

- Sounds and Colours Archived 2020-10-09 at the Wayback Machine—magazine about South American music and culture

- World Music at SKY.FM Archived 2013-03-26 at the Wayback Machine—A free world music radio channel

- World Music Central Archived 2015-06-17 at the Wayback Machine—World Music news, reviews, articles and resources

- Rhythm Passport Archived 2015-06-08 at the Wayback Machine—World music/global beats event listings website for the UK

- Wilde Töne – Festival for Folk- and Weltmusic Archived 2019-11-17 at the Wayback Machine in Braunschweig, Germany