Billy Idol

Billy Idol | |

|---|---|

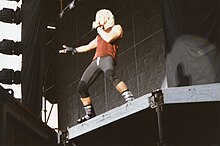

Idol performing with supergroup Generation X in 2023 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | William Michael Albert Broad |

| Born | 30 November 1955 Stanmore, Middlesex England |

| Genres | |

| Occupations |

|

| Instruments |

|

| Years active | 1976–present |

| Labels | |

| Member of | Generation X |

| Formerly of | |

| Website | billyidol |

William Michael Albert Broad (born 30 November 1955), known professionally as Billy Idol, is an English punk singer, songwriter, musician and actor. He achieved fame in the 1970s emerging from the London punk rock scene as the lead singer of the group Generation X. Subsequently, he embarked on a solo career which led to international recognition and made Idol a lead artist during the MTV-driven "Second British Invasion" in the US.

Idol began his music career in late 1976 as a guitarist in the punk rock band Chelsea; he left the group after a few weeks. With his former bandmate Tony James, Idol formed Generation X. With Idol as lead singer, the band achieved success in the United Kingdom and released three studio albums on Chrysalis Records, then disbanded. In 1981, Idol moved to New York City to pursue his solo career in collaboration with guitarist Steve Stevens. His debut studio album, Billy Idol (1982), was a commercial success. With music videos for singles "Dancing with Myself" and "White Wedding" Idol became a staple of the newly established MTV.

Idol's second studio album, Rebel Yell (1983), was a major commercial success, featuring hit singles "Rebel Yell" and "Eyes Without a Face". The album was certified double platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) for shipment of two million copies in the US. In 1986, he released Whiplash Smile. Idol released a 1988 greatest hits album titled Idol Songs: 11 of the Best; the album went platinum in the United Kingdom. Idol released Charmed Life (1990) and the concept album Cyberpunk (1993).

Idol spent the second half of the 1990s focusing on his personal life out of the public eye. In 1990, he had a motorcycle accident in which he broke his leg. In his 2014 biography Dancing With Myself, Idol stated "that by the time the motorcycle accident happened, he'd been living by the credo, 'Live every day as if it's your last, and one day you're sure to be right.'"[1] He made a musical comeback with the release of Devil's Playground (2005) and later released Kings & Queens of the Underground (2014).

Early life

[edit]Idol was born William Michael Albert Broad on 30 November 1955 in Stanmore, Middlesex, England.[2] His parents attended Church of England services regularly. Idol is half Irish; his mother, whose maiden name was O'Sullivan, was born in Cork. He qualifies for Irish citizenship through his mother.[3][4]

In 1958, when he was two years old, he moved with his parents to the US and settled in Patchogue, New York; they also lived in Rockville Centre, New York (both on Long Island). His younger sister, Jane, was born during this time. The family returned to England four years later and settled in Dorking, Surrey.[5] In 1971, when Idol was 15, the family moved to Bromley in southeastern Greater London, where Idol attended Ravensbourne School for Boys. His family later moved to Worthing to the suburb of Goring-by-Sea in West Sussex, where he attended Worthing High School for Boys.[6] In October 1975, he began attending the University of Sussex to pursue a Philosophy with Literature degree but left after year one in 1976. He joined the Bromley Contingent of Sex Pistols fans, a loosely organised gang that travelled to see the band wherever they played.[7][8]

Career

[edit]1976–1981: Generation X

[edit]The name "Billy Idol" was coined due to a chemistry teacher's description of Idol on his school report card as "idle". Idol has stated that the subject was one that he hated and in which he underachieved.[9][10] In an interview on 21 November 1983, Idol said the name "Billy Idol" "was a bit of a goof, but part of the old English school of rock. It was a 'double thing', not just a poke at the superstar-like people... It was fun, you know?"[11][10] In another interview for BBC Breakfast in October 2014, he said that he wanted to use the name "Billy Idle", but thought the name would be unavailable due to its similarity to the name of Monty Python star Eric Idle and chose Billy Idol instead.[12]

In late 1976, he joined the newly formed West London 1960s retro-rock band Chelsea as a guitarist.[13] The act's singer/frontman Gene October styled Idol's image, advising him to use contact lenses instead of eyeglasses for his short sight, and dye his hair blonde with a crew cut for a retro-1950s rocker look. After a few weeks performing with Chelsea, Idol and Tony James, the band's bass guitarist, quit and co-founded Generation X, with Idol switching from guitarist to the role of singer/frontman. Generation X was one of the first punk bands to appear on the BBC Television music programme Top of the Pops.[14] Although a punk rock band, they were inspired by mid-1960s British pop, in sharp contrast to their more militant peers, with Idol stating, "We were saying the opposite to the Clash and the Pistols. They were singing 'No Elvis, Beatles or the Rolling Stones', but we were honest about what we liked. The truth was we were all building our music on the Beatles and the Stones."[7] In 1977, Idol sang "Your Generation" on the TV series Marc. Generation X signed a recording contract with Chrysalis Records, released three studio albums, performed in the 1980 film D.O.A.: A Rite of Passage, and then disbanded.[15]

1981–1985: Solo career and breakthrough

[edit]"MTV has paved the way for a host of invaders from abroad: Def Leppard, Adam Ant, Madness, Eurythmics, the Fixx and Billy Idol, to name a few. In return, grateful Brits, even superstars like Pete Townshend and the Police, have mugged for MTV promo spots and made the phrase 'I want my MTV' a household commonplace."

Idol moved to New York City in 1981 and became a solo artist, working with former Kiss manager Bill Aucoin. Idol's punk-like image worked well with the glam rock style of his new partner on guitar, Steve Stevens.[17] Together they worked with bassist Phil Feit and drummer Gregg Gerson. Idol's solo career began with the Chrysalis Records EP titled Don't Stop in 1981, which included the Generation X song "Dancing with Myself", originally recorded for their last album Kiss Me Deadly, and a cover of Tommy James and the Shondells' song "Mony Mony". Idol's debut solo album Billy Idol was released in July 1982.[18]

Part of the MTV-driven "Second British Invasion" of the US in 1982, Idol became an MTV staple with "White Wedding" and "Dancing with Myself". The music video for "White Wedding" was filmed by the British director David Mallet and played frequently on MTV. The motorcycle smashing through the church window stunt was carried out by John Wilson, a London motorcycle courier. In 1983, Idol's label released "Dancing with Myself" in the US in conjunction with a music video directed by Tobe Hooper, which played on MTV for six months.[citation needed]

Rebel Yell (1983), Idol's second LP, was a major success[19] and established Idol in the United States with hits such as "Rebel Yell", "Eyes Without a Face", and "Flesh for Fantasy". "Eyes Without a Face" peaked at number four on the US Billboard Hot 100, and "Rebel Yell" reached number six in the UK Singles Chart.[20][21]

1986–1992: Whiplash Smile and Charmed Life

[edit]

Idol released Whiplash Smile in 1986, which sold well.[19] The album included the hits "To Be a Lover", "Don't Need a Gun" and "Sweet Sixteen". Idol filmed a video for the song "Sweet Sixteen" in Florida's Coral Castle.[22]

A remix album was released in 1987, titled Vital Idol. The album featured a live rendition of his cover of Tommy James' "Mony Mony". In 1987, the single topped the United States chart and reached number 7 in the UK.[19][21]

On 6 February 1990 in Hollywood, Idol was involved in a serious motorcycle accident that nearly cost him a leg.[23] He was hit by a car when he ran a stop sign while riding home from the studio one night, requiring a steel rod to be placed in his leg.[24] While he was hospitalised, he vowed to stop wearing clothing featuring the Confederate flag, after a black employee tending to him explained his feelings on it.[25][26]

Prior to the accident, film director Oliver Stone had chosen Idol for the role of Jim Morrison's drinking pal Cat in his film The Doors (1991), but it prevented him from participating in a major way and Idol's role was reduced to a small part.[27] He was James Cameron's first choice for the role of the villainous T-1000 in Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991); the role was recast as a result of the accident.[28]

Charmed Life was released in 1990, and a video for the single "Cradle of Love" had to be shot. The song was featured in the Andrew Dice Clay film The Adventures of Ford Fairlane. Because Idol was unable to walk due to injuries he sustained in a motorcycle accident,[29] he was shot from the waist up. The video featured video footage of him singing in large frames throughout an apartment while Betsy Lynn George was trying to seduce a businessman. The video was placed in rotation on MTV. "Cradle of Love" earned Idol a third Grammy nomination for Best Male Rock Vocal Performance.[30]

1993–2004: Cyberpunk, decline, and resurgence

[edit]

In 1993, Idol released Cyberpunk.[31] Regarded as experimental, it was recorded in a home studio using a Macintosh computer. Idol used Studiovision and Pro Tools to record the album. The album took ten months to make. The album did not perform well in the United States and the lead single "Shock to the System" did not chart in the Billboard Hot 100. In comparison, the lead single from Idol's previous album, "Cradle of Love", peaked at No. 2. In Europe, the album fared slightly better, achieving moderate chart success and peaking within the UK top 20. Idol toured in Europe and played a Generation X reunion show in 1993.[32]

He recorded and released the single "Speed" in 1994; the song was featured as the first track in the film soundtrack album. Idol appeared in a 1996 live version of the Who's Quadrophenia.[33] Idol made a cameo appearance as himself in the 1998 film The Wedding Singer with Adam Sandler, in which Idol played a pivotal role in the plot. The film featured "White Wedding" on its soundtrack.[34] In 2000, he was invited to be a guest vocalist on Tony Iommi's debut solo album. His contribution was on the song "Into the Night", which he co-wrote. That year, he voice acted the role of Odin, a mysterious alien character, in the adult animated science fiction film Heavy Metal 2000, also providing a song for the soundtrack.[citation needed]

VH1 aired Billy Idol – Behind the Music on 16 April 2001. Idol and Stevens took part in a VH1 Storytellers show three days later. The reunited duo set out to play a series of acoustic/storytellers shows before recording the VH1 special. Another Greatest Hits CD was issued in 2001, with Keith Forsey and Simple Minds' "Don't You (Forget About Me)" appearing on the compilation. The LP includes a live acoustic version of "Rebel Yell", taken from a performance at Los Angeles station KROQ's 1993 Acoustic Christmas concert. The Greatest Hits album sold 1 million copies in the United States alone.[citation needed]

In the 2002 NRL Grand Final in Sydney, Idol entered the playing field for the half-time entertainment on a hovercraft to the intro of "White Wedding", of which he managed to sing only two words before a power failure ended the performance.[35]

2005–2009: Devil's Playground

[edit]

Devil's Playground, which came out in March 2005, was Idol's first new studio album in nearly 12 years. The album reached No. 46 on the Billboard 200. The album included a cover of "Plastic Jesus". Idol played a handful of dates on the 2005 Warped Tour and appeared at the Download Festival at Donington Park, the Voodoo Music Experience in New Orleans, and Rock am Ring.[36]

In 2008, "Rebel Yell" appeared as a playable track on the video game Guitar Hero World Tour and "White Wedding" on Rock Band 2. The Rock Band 2 platform later gained "Mony Mony" and "Rebel Yell" as downloadable tracks. On 24 June 2008, Idol released the greatest hits album The Very Best of Billy Idol: Idolize Yourself. He embarked on a worldwide tour, co-headlining with Def Leppard.[citation needed]

In June 2006, Idol performed at the Congress Theater, Chicago, for the United States television series Soundstage. This performance was recorded and then released on DVD/Blu-ray as In Super Overdrive Live, on 17 November 2009.[37][38]

2010–present: Kings & Queens of the Underground

[edit]

On 16 February 2010, Idol was announced as one of the acts to play at the Download Festival in Donington Park, England. He stated, "With all of these great heavyweight and cool bands playing Download this year, I'm going to have to come armed with my punk rock attitude, Steve Stevens, and all of my classic songs plus a couple of way out covers. Should be fun!"[39] In March 2010, Idol added Camp Freddy guitarist Billy Morrison[40] and drummer Jeremy Colson to his touring line-up.

In 2013, Idol appeared on the third episode of the BBC Four series How the Brits Rocked America.[41] Idol also lent his voice as Spikey Hair Bot to Disney XD's Randy Cunningham: 9th Grade Ninja episode "McSatchle"[42][43]

In October 2014, Idol released his eighth studio album Kings & Queens of the Underground. While recording the album between 2010 and 2014, he worked with producer Trevor Horn, Horn's former Buggles and Yes bandmate Geoff Downes[44] and Greg Kurstin. Idol's autobiography, Dancing with Myself, was published on 7 October 2014 and became a New York Times bestseller.[45]

On 30 October 2018, former Generation X members Idol and Tony James joined with Steve Jones and Paul Cook, former members of another first wave English punk rock band, the Sex Pistols, to perform a free gig at the Roxy in Hollywood, Los Angeles, under the name Generation Sex, playing a combined set of the two former bands' material.[46]

In late February 2020, Idol starred in a public service campaign with the New York City Department of Environmental Protection Police titled "Billy Never Idles", intended to fight the unnecessary idling of automobile engines in New York City, to reduce air pollution. Idol teamed with New York Mayor Bill de Blasio to open the campaign, which features Idol saying, "If you're not driving, shut your damn engine off!" and other strong advice.[47] He was a guest vocalist on the song "Night Crawling" from Miley Cyrus' album Plastic Hearts, released in November 2020.[48] In 2016, Idol and Cyrus performed "Rebel Yell" at the iHeartRadio Festival in Las Vegas.[49]

On 12 August 2021, Idol's music video "Bitter Taste", directed by Stephen Sebring, was uploaded to YouTube. Idol announced his new EP The Roadside, which was released on 17 September.[50] Another EP, The Cage, was released on 23 September 2022. A video for the title track, also directed by Sebring, premiered on YouTube 17 August.

In March 2022, Idol was diagnosed with MRSA, which forced him to cancel a co-headlining tour with Journey.[51]

In September 2022, he embarked on the postponed Roadside Tour with Killing Joke and Toyah as his UK opening acts in October.[52][53]

On 6 January 2023, Idol was honoured with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.[54] On 24 January, he announced a North American tour from late March through mid-May: the tour was to begin in Scottsdale on 30 March and conclude with a concert at the Cruel World Festival on 20 May in Pasadena.[55]

In April that year, Idol played the first concert in history at the Hoover Dam.[56]

Idol is a member of Generation X who are on tour and performed at Glastonbury in 2023.[57]

Live band

[edit]Idol's live band consists of:[58]

- Billy Idol – lead vocals (1981–present)

- Steve Stevens – lead and rhythm guitar, keyboards, backing vocals (1981–1987, 1993–1995, 1999–present)

- Stephen McGrath – bass, backing vocals (2001–present)

- Billy Morrison – rhythm and lead guitar, backing vocals (2010–present)

- Erik Eldenius – drums (2012–present)

- Paul Trudeau – keyboards, backing vocals (2014–present)

Former members

- Phil Feit – bass (1981–1983)

- Steve Missal – drums (1981–1982)

- Gregg Gerson – drums (1982–1983)

- Judi Dozier – keyboards (1982–1985)

- Steve Webster – bass (1983–1985)

- Thommy Price – drums (1983–1987)

- Kenny Aaronson – bass (1986–1987)

- Susie Davis – keyboards, backing vocals (1986–1987)

- Mark Younger-Smith – guitars, keyboards (1988–1993)

- Phil Soussan – bass (1988–1990)

- Larry Seymour – bass (1990–1996)

- Tal Bergman – drums (1990–1993)

- Bonnie Hayes – keyboards, backing vocals (1990–1991)

- Jennifer Blakeman – keyboards, backing vocals (1993)

- Julie Greaux – keyboards, backing vocals (1993)

- Danny Sadownik – drums (1993)

- Mark Schulman – drums (1993–2001)

- Sasha Krivtsov – bass (2000)

- Brian Tichy – drums (2001–2009)

- Jeremy Colson – drums (2010–2012)

- Derek Sherinian – keyboards (2002–2014)

Timeline

[edit]

Personal life

[edit]Idol has never married, but was in a long-term relationship with English singer, dancer, and former Hot Gossip member Perri Lister. They have a son, Willem, who was born in Los Angeles in 1988[59] and who has been a member of the rock band FIM.[60] Lister and Idol separated in 1989.[61] Idol also has a daughter from a relationship with Linda Mathis.[62][63]

Idol has struggled with alcoholism and drug addiction. His drug history includes heroin and cocaine.[64] In his 2014 memoir, he said he passed out more than once in nightclubs only to then wake up in a hospital.[65] In 1994, Idol collapsed outside a Los Angeles nightclub due to an overdose[66] of the drug GHB.[67] After the incident, Idol decided that his children would never forgive him for dying of a drug overdose, and he stopped his drug use.[68] In 2014, Idol said he had not taken hard drugs since 2003, but added that he smoked cannabis regularly and was an occasional drinker.[64]

In 2018, Idol became a naturalised American citizen during a ceremony in Los Angeles, while retaining his British citizenship.[69] Idol has two grandchildren.[70]

Discography

[edit]Studio albums

[edit]- Billy Idol (1982)

- Rebel Yell (1983)

- Whiplash Smile (1986)

- Charmed Life (1990)

- Cyberpunk (1993)

- Devil's Playground (2005)

- Happy Holidays (2006)

- Kings & Queens of the Underground (2014)

Extended plays

[edit]- Don't Stop (1981)

- The Roadside (2021)

- The Cage (2022)

Awards and nominations

[edit]ASCAP Pop Music Awards

[edit]| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1991 | "Cradle of Love" | Most Performed Song | Won | [71] |

Classic Rock Roll of Honour Awards

[edit]| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | Himself | Comeback of the Year | Won | [72] |

Grammy Awards

[edit]| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1985 | "Rebel Yell" | Best Male Rock Vocal Performance | Nominated | [73][74] |

| 1987 | "To Be a Lover" | Nominated | [75][76] | |

| 1991 | "Cradle of Love" | Nominated | [77] |

MTV Video Music Awards

[edit]The MTV Video Music Awards is an annual awards ceremony established in 1984 by MTV.

| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1984 | "Dancing with Myself" | Best Direction | Nominated |

| 1984 | "Dancing with Myself" | Best Art Direction | Nominated |

| 1984 | "Dancing with Myself" | Best Special Effects | Nominated |

| 1984 | "Eyes Without a Face" | Best Cinematography | Nominated |

| 1984 | "Eyes Without a Face" | Best Editing | Nominated |

| 1990 | "Cradle of Love" | Best Video from a Film | Won[78] |

| 1990 | "Cradle of Love" | Best Male Video | Nominated |

| 1990 | "Cradle of Love" | Best Special Effects | Nominated |

| 1993 | "Shock to the System" | Best Special Effects | Nominated |

| 1993 | "Shock to the System" | Best Editing | Nominated |

Brit Awards

[edit]The Brit Awards are the British Phonographic Industry's annual pop music awards.[79]

| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1991 | Billy Idol – "Cradle of Love" | Best British Video | Nominated |

Pollstar Concert Industry Awards

[edit]| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1988 | Tour | Most Creative Tour Package | Nominated | [80] |

References

[edit]- ^ https://www.grunge.com/253562/the-truth-about-billy-idols-horrific-motorcycle-accident/

- ^ Guinness 1992, p. 1222.

- ^ Dermody, Joe (18 June 2015). "Live at the Marquee: Billy's still an Idol in Rebel County". Irish Examiner. Retrieved 5 January 2024.

- ^ Idol, Billy [@BillyIdol] (30 July 2012). "Just to show u where my heart lies..." (Tweet). Retrieved 23 July 2022 – via Twitter.

- ^ "Film Reference biography". Filmreference.com. Retrieved 11 October 2011.

- ^ Idol, Billy (2015). Dancing with Myself. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9781451628517.[page needed]

- ^ a b "Billy Idol: the return of Billy the kid". The Daily Telegraph. London. 24 July 2008. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- ^ Marko, Paul (2007). The Roxy London WC2: A Punk History. ISBN 9780955658303. Retrieved 9 April 2014.[page needed]

- ^ Edmunds, Ben, untitled essay in Greatest Hits (2001)

- ^ a b Hay, Karyn (April 1984). Radio with Pictures. Television New Zealand. Event occurs at 04:30s. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- ^ ConcertVault interview 21 November 1983

- ^ "BBC Breakfast Billy Idol Interview (27 October 2014)" on YouTube. BBC. Retrieved 28 October 2014

- ^ "Chelsea". steveharnett.com. Archived from the original on 30 January 2016. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ "Biography by Greg Prato". AllMusic. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ^ "Gold & Platinum". RIAA. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- ^ "Anglomania: The Second British Invasion". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- ^ "Vernon Reid – Guitar World interview (part 3) Cult of Personality". The Biography Channel. 15 February 2010. Archived from the original on 30 December 2011. Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- ^ William Ruhlmann. "Billy Idol - Billy Idol | Songs, Reviews, Credits, Awards". AllMusic. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- ^ a b c "Billy Idol Music News & Info". Billboard. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- ^ Whitburn, Joel (2006). The Billboard Book of Top 40 Hits. Billboard Books

- ^ a b Roberts, David (2006). British Hit Singles & Albums (19th ed.). London, England: Guinness World Records Limited. p. 266. ISBN 1-904994-10-5.

- ^ "FAQs- Coral Castle Museum". Archived from the original on 5 November 2021. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- ^ Marilyn Monroe Died Here – More Locations of America's Pop Culture Landmarks by Chris Epting, p. 185

- ^ Biography for Billy Idol at IMDb

- ^ Idol, Billy [@BillyIdol] (23 June 2015). "A black man washed my hair in hospital '90 & explained his feelings on seeing the Confederate flag, I promised him I would never wear it" (Tweet). Retrieved 5 January 2024 – via Twitter.

- ^ Idol, Billy [@BillyIdol] (23 June 2015). "I never wear the Confederate battle flag ever since 1990 as I realized it symbolizes oppression to certain Americans..." (Tweet). Retrieved 5 January 2024 – via Twitter.

- ^ Kilday, Gregg (8 March 1991). "Faces in the Crowd". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 21 October 2014. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- ^ "Billy Idol Almost Played the T-1000 in 'Terminator 2,' Robert Patrick Says". The Hollywood Reporter. 17 August 2017.

- ^ "Billy Idol's Motorcycle Accident". grunge.com. 29 September 2020. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- ^ "Billy Idol". Rock on the Net. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- ^ "20 Years Ago: Billy Idol's 'Cyberpunk' Album Released". Ultimate Classic Rock. 29 June 2013.

- ^ "Billy Idol wants Generation X reunion". 3news.co.nz. Archived from the original on 7 November 2014. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ^ Dave White. "About Classic Rock - Review Who "Tommy/Quadrophenia" DVD". About.com Entertainment. Archived from the original on 12 July 2014. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ^ The Wedding Singer (1998) - IMDb, retrieved 27 October 2021

- ^ "Idol idle: rebel's yell silenced". The Age. 7 October 2002. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- ^ "Rock am Ring 2005". ringrocker.com. Archived from the original on 10 October 2011. Retrieved 11 October 2011.

- ^ "Billy Idol · Super Overdrive Live DVD". Archived from the original on 19 October 2009. Retrieved 21 October 2009.

- ^ "06/28/2006: Billy Idol @ Congress Theater | Concert Archives". www.concertarchives.org. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- ^ "Billy Idol announced to play Download 2010". Downloadfestival.co.uk. Archived from the original on 19 November 2012. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- ^ "Billy Morrison: MORRISON WITH IDOL 2010". 11 May 2011. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011.

- ^ "BBC Four - How the Brits Rocked America: Go West". BBC. 18 October 2013. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- ^ Wolfe, Jennifer (12 September 2013). "'Randy Cunningham 9th Grade Ninja' Returns for Second Series". Animation World Network. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- ^ Ungerman, Alex (25 October 2013). "Billy Idol is a Punk Robot on 'Randy Cunningham'". Entertainment Tonight. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- ^ "Album of the Week: Stream 'Zang Tuum Tumb,' a 27-Track History of ZTT Records". Spin. 8 October 2013. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- ^ "Billy Idol to Release First New Album in Nearly a Decade". The Hollywood Reporter. 17 June 2014. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- ^ "Generation Sex: King Rockers and Silly Things at the Roxy". LA Weekly. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ^ Judy Kurtz (28 February 2020). "Billy Idol, de Blasio launch anti-car idling campaign in New York: 'Billy never idles'". The Hill. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ Kreps, Daniel (20 November 2020). "Miley Cyrus Talks Working With Billy Idol on New Song 'Night Crawling' - Rolling Stone". Rolling Stone.

- ^ Carter, Simone. "From Def Leppard to Elton John, Here Are Miley Cyrus' Most Powerful Collabs". Newsweek, 30 September 2022. Retrieved 21 October 2022

- ^ "The Roadside – brand new 4-song EP". Billy Idol. 11 August 2021. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ^ "Billy Idol is Still Battling Dangerous Staph Infection". 14 March 2022.

- ^ "Killing Joke joins Billy Idol Roadside Tour after illness forces Television to pull out". 6 October 2022.

- ^ "Billy Idol".

- ^ "BILLY IDOL TO BE HONORED WITH FIRST HOLLYWOOD FAME STAR OF 2023". Hollywood Walk of Fame Official Site. 6 January 2023.

- ^ "Rebel on the Road: Billy Idol Plots 2023 North American Tour Dates". Rolling Stone. 23 January 2023.

- ^ Duran, Anagricel (19 April 2023). "Billy Idol makes history by playing first ever concert at the Hoover Dam". NME. Retrieved 22 April 2023.

- ^ "Generation Sex – Acts – Glastonbury". BBC.

- ^ "Band". BillyIdol.net. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- ^ .Hochman, Steve (1999). Popular Musicians: The Doobie Brothers-Paul McCartney. Salem Press. p.512

- ^ Amica magazine. Milan, Italy: RCS Mediagroup S.p.A. #1 January 2012

- ^ "Billy Idol biography". Archived from the original on 1 July 2009. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- ^ "Billy Idol". Cbsnews.com. 5 October 2014. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- ^ Roura, Phil (11 September 2010). "Wild at heart: Billy Idol may be a proud dad, but there's no taming the rocker". New York Daily News.

- ^ a b McClurg, Jocelyn. "Billy Idol is as 'candid as possible' in new memoir". USA TODAY.

- ^ "Billy Idol: Sex, Drugs, 'Charmed Life,' and the Crash That Nearly Killed Me". Time.

- ^ "Rock Idol Leaves Hospital After Treatment for Overdose". Tulsa World. 8 August 1994.

- ^ Both Billy Idol and his friend John Diaz discuss this incident/drug in MTV BTM interview 2001 "MTV Behind the Music". 5 December 2013. Archived from the original on 21 December 2021. Retrieved 15 June 2014 – via YouTube.

- ^ Meisfjord, Tom (28 July 2020). "You probably wouldn't want to meet Billy Idol in real life. Here's why". Grunge.com.

- ^ Folley, Aris (17 November 2018). "Billy Idol becomes a US citizen". The Hill.

- ^ Trakin, Roy (5 January 2023). "Billy Idol on Getting the Mark of a True Idol: a Star on Hollywood Walk of Fame". Variety. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ "ASCAP Pop Awards Honor Most-Performed Songs" (PDF). Billboard. 25 May 1991. p. 71. Retrieved 28 September 2021.

- ^ "Classic Rock Roll of Honour Awards: Winners Announced". blabbermouth.net. 4 October 2005. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ "Turner, Prince, Richie top out the Grammys". The Deseret News. 27 February 1985. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- ^ "1984 Grammy Award Winners". Grammy.com. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- ^ "Simon's controversial album wins most prestigious Grammy". The Deseret News. 25 February 1987. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- ^ "1986 Grammy Award Winners". Grammy.com. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- ^ "33rd Annual Grammy Awards". The Recording Academy. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- ^ "vma 1990: about the show". MTV. Viacom. 6 September 1990. Archived from the original on 17 June 2016. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- ^ "Billy Idol nomination for 1991 BRIT Awards Best British Video". Brit Awards. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- ^ "Pollstar Awards Archive - 1987". 20 March 2017. Archived from the original on 20 March 2017.

Reference bibliography

[edit]- Larkin, Colin, ed. (1992). "Idol, Billy". The Guinness Encyclopedia of Popular Music. Vol. 2: Farian, Frank to Menza, Don. Guinness.

Further reading

[edit]- Gilbert, Pat (December 2014). "Just William". Mojo. 253 (6): 54–57.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Billy Idol at AllMusic

- Billy Idol discography at Discogs

- Billy Idol at IMDb

- Billy Idol at Rolling Stone

- Billy Idol[usurped] interview @ Legends

- [1]

- [2]

- 1955 births

- 20th-century English male actors

- 20th-century English male singers

- 21st-century English male actors

- 21st-century English male singers

- Actors from Dorking

- Actors from the London Borough of Bromley

- Actors from the London Borough of Harrow

- Alumni of the University of Sussex

- Brit Award winners

- British hard rock musicians

- British post-punk musicians

- Bromley Contingent

- Chelsea (band) members

- Chrysalis Records artists

- EMI Records artists

- English expatriate male actors in the United States

- English expatriate musicians in the United States

- English male film actors

- English male new wave singers

- English male singer-songwriters

- English new wave singers

- English people of Irish descent

- English punk rock singers

- English rock singers

- Generation X (band) members

- Glam rock musicians

- Living people

- Male actors from Kent

- Male actors from Surrey

- Musicians from Kent

- Musicians from the London Borough of Bromley

- Musicians from the London Borough of Harrow

- Naturalized citizens of the United States

- Neurotic Outsiders members

- People educated at Ravensbourne School, Bromley

- People educated at Worthing High School

- People from Bromley

- People from Goring-by-Sea

- People from Stanmore

- Sanctuary Records artists

- Second British Invasion artists

- Singers from the London Borough of Bromley

- Singers from the London Borough of Harrow