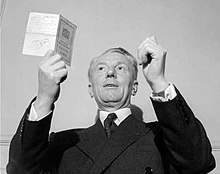

Harry Willcock

Clarence Harry Willcock (23 January 1896 – 12 December 1952) was a British Liberal Party activist and dry cleaning firm manager. He is best remembered for being the last person in the United Kingdom to be prosecuted for refusing to produce an identity card, a wartime requirement introduced in 1939 but which was continued after the war by the post-war Attlee government.

Life

[edit]Willcock was born in Alverthorpe, Wakefield, Yorkshire, the illegitimate son of Harry Cruickshank, a native of Leeds who worked in the textile trade, and Ella Brooke, whose family were wholesalers to tailors. He was adopted by a widow, Mary Willcock, whose surname he adopted. During World War I he served with the Northumberland Fusiliers, but was not sent overseas.[1]

He was active in Liberal politics – a councillor and magistrate in Horsforth – then stood for Parliament as candidate in Barking in 1945 and 1950, coming third – last (at the first exceeding 12.5% of the vote, at which his deposit was refunded).[1] At the time of the events which gave rise to Willcock v. Muckle, he was the manager of a successful dry cleaning firm in London.[1]

Willcock v. Muckle

[edit]Compulsory identity cards had been re-introduced in World War II under the National Registration Act 1939.[2] After the war, in 1945, the Attlee government chose to continue them.

On 7 December 1950, Willcock was stopped for speeding on Ballard's Lane, North Finchley, London. Police Constable Harold Muckle asked him to produce his card. Willcock refused, reportedly saying "I am a Liberal, and I am against this sort of thing". Muckle gave Willcock a form to produce his card at any police station within two days, to which Willcock replied "I will not produce it at any police station and I will not accept the form".[3] He then threw the form on the ground. Willcock failed to produce the form within this time, and was prosecuted under the Act.[1]

To the Highgate justices, he argued that the power to require the production of such a card had lapsed when the state of emergency which led to the passage of the Act had expired.[1] The justices rejected this, but gave him an absolute discharge.[1] Separately, he was fined 30s for speeding.

He appealed the guilty but no-reprimand verdict to the High Court by way of case stated (meaning the bench agreed a certified point of law had arisen).[3] Unusually, this was heard by a bench of seven judges in a divisional court, which included the Lord Chief Justice, Lord Goddard, and Sir Raymond Evershed MR.[3] His defence team comprised prominent Liberals including Archibald Pellow Marshall KC, Emrys Roberts MP, and Basil Wigoder, who offered their services free. Sir Frank Soskice, the Attorney General, appeared as amicus curiae.[3]

The verdict was upheld. A majority of the Court (Lord Goddard CJ, Somervell and Jenkins LJJ, Hilbery and Lynskey JJ; against Evershed MR and Devlin J dubitantibus) held that the Act remained in force, as no Order in Council had specifically terminated it. However, Lord Goddard was critical of the Government:

"This Act was passed for security purposes; it was never passed for the purposes for which it is now apparently being used. To use Acts of Parliament passed for particular purposes in wartime when the war is a thing of the past—except for the technicality that a state of war exists—tends to turn law-abiding subjects into lawbreakers, which is a most undesirable state of affairs. Further, in this country we have always prided ourselves on the good feeling that exists between the police and the public, and such action tends to make the people resentful of the acts of the police, and inclines them to obstruct the police instead of assisting them. For these reasons I hope that if a similar case comes before any other bench of justices, they will deal with it as did the Highgate bench and grant the defendant an absolute discharge, except where there is a real reason for demanding sight of the registration card."[3]

The Court dismissed the appeal, but did not award costs against Willcock.

Aftermath and later life

[edit]For this, Willcock became well-known and he founded the Freedom Defence Association to campaign against identity cards. In a publicity event, he tore up his own identity card in front of the National Liberal Club, inspiring in April 1951 a similar action for the press outside Parliament by the British Housewives' League.[1]

The Party's stance to the campaign was soon cast as 'half-hearted', possibly as he was aligned with the free-trade wing – the issue of identity cards was left out of its manifesto for the 1951 elections.[1]

Defeating the Labour government in the general election of 1951, the Conservative government of Winston Churchill put to Conference abolition to 'set the people free', in the words of a minister. On 21 February 1952 the Minister of Health, Harry Crookshank, announced in the Commons that the cards were to be scrapped. This was a popular move but against the consensus of the police and the security services.

On abolition Willcock was sent hundreds of cards, via post, to auction for charity. In 1952, he forced an election for the four honorary vice-presidents of the Liberal Party, but lost.[1]

He died suddenly while debating at a meeting of the Eighty Club at the Reform Club. The last word on his lips before his death was reported to have been "freedom."[1]

Willcock is commemorated by a plaque in the National Liberal Club.[4] Former Deputy Prime Minister and Liberal Democrat leader Nick Clegg has described Willcock as one of his heroes.[5][6]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Ingham, Robert. "Willcock, (Clarence) Harry (1896–1952)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/61805. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ 2 & 3 Geo. 6, c. 9

- ^ a b c d e Willcock v. Muckle [1951] 2 KB 844

- ^ "Harry Willcock". The Scotsman. 14 June 2006. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- ^ Brack, Duncan (26 November 2007). "Old Heroes for a New Leader: Nick Clegg". Liberal Democrat Voice. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- ^ Membery, York (13 November 2011). "My history hero: Clarence Willcock". History Extra. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

External links

[edit]- "Policing by plastic" by Alan Travis; The Guardian, 30 May 2003

- "Harry Willcock: the forgotten champion of Liberalism" by Mark Egan in Journal of Liberal Democrat History; issue 17, Winter 1997

- Liberal Democrat leader Nick Clegg MP on why Willcock is one of his personal heroes, 29 October 2009