Wikipedia in culture

References to Wikipedia in popular culture have been widespread. Many parody Wikipedia's openness, with individuals vandalizing or modifying articles in nonconstructive ways. Others feature individuals using Wikipedia as a reference work, or positively comparing their intelligence to Wikipedia. In some cases, Wikipedia is not used as an encyclopedia at all, but instead serves more as a character trait or even as a game, such as Wikiracing. Wikipedia has also become culturally significant with many individuals seeing the presence of their own Wikipedia entry as a status symbol.[1]

References to Wikipedia

[edit]Wikiality

[edit]In a July 2006 episode of the satirical comedy The Colbert Report, Stephen Colbert announced the neologism "wikiality", a portmanteau of the words Wiki and reality, for his segment "The Wørd". Colbert defined wikiality as "truth by consensus" (rather than fact), modeled after the approval-by-consensus format of Wikipedia. He ironically praised Wikipedia for following his philosophy of truthiness in which intuition and consensus is a better reflection of reality than fact:

You see, any user can change any entry, and if enough other users agree with them, it becomes true. ... If only the entire body of human knowledge worked this way. And it can, thanks to tonight's word: Wikiality. Now, folks, I'm no fan of reality, and I'm no fan of encyclopedias. I've said it before. Who is Britannica to tell me that George Washington had slaves? If I want to say he didn't, that's my right. And now, thanks to Wikipedia, it's also a fact. We should apply these principles to all information. All we need to do is convince a majority of people that some factoid is true. ... What we're doing is bringing democracy to knowledge.[2]

According to Stephen Colbert, together "we can all create a reality that we all can agree on; the reality that we just agreed on". During the segment, he joked: "I love Wikipedia... any site that's got a longer entry on truthiness than on Lutherans has its priorities straight." Colbert also used the segment to satirize the more general issue of whether the repetition of statements in the media leads people to believe they are true. The piece was introduced with the tagline "The Revolution Will Not Be Verified", a play on the song title "The Revolution Will Not Be Televised" referencing how the mainstream establishment that Wikipedia cites as Reliable Sources will not support significant change, throwing doubt on the idea that Wikipedia is truthful.

Colbert suggested that viewers change the elephant page to state that the number of African elephants has tripled in the last six months.[3] The suggestion resulted in numerous incorrect changes to Wikipedia articles related to elephants and Africa.[a] Wikipedia administrators subsequently restricted edits to the pages by anonymous and newly created user accounts.

Colbert went on to type on a laptop facing away from the camera, claiming to be making the edits to the pages himself. Because initial edits to Wikipedia corresponding to these claimed "facts" were made by a user named Stephencolbert, many believe Colbert himself vandalized several Wikipedia pages at the time he was encouraging other users to do the same. The account, whether it was Stephen Colbert himself or someone posing as him, has been blocked from Wikipedia indefinitely.[4] Wikipedia blocked the account for violating Wikipedia's username policies (which state that using the names of celebrities as login names without permission is inappropriate), not for the vandalism, as believed.

Other instances

[edit]In art

[edit]

The Wikipedia Monument, located in Słubice, Poland, is a statue designed by Armenian sculptor Mihran Hakobyan honoring Wikipedia contributors. It was unveiled in Frankfurt Square (Plac Frankfurcki) on 22 October 2014 in a ceremony that included representatives from both local Wikimedia chapters and the Wikimedia Foundation.[5][6]

In music

[edit]A scene in the 2006 music video for the "Weird Al" Yankovic song "White & Nerdy", show Yankovic vandalizing the Wikipedia page for Atlantic Records, replacing it with the words "YOU SUCK!", referencing recent trouble he had had with the company in getting permissions.[7]

Ukrainian composer Andriy Bondarenko wrote a musical piece, "Anthem of Wikipedia", which was performed in a concert devoted to the 15th anniversary of Wikipedia in Kyiv in 2016.[8][9]

In webcomics

[edit]

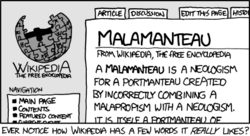

References to Wikipedia have been made several times in the webcomic xkcd. A facsimile of a made-up Wikipedia entry for "malamanteau" (a stunt word created by Munroe to poke fun at Wikipedia's writing style) provoked a controversy.[10][11]

In humor

[edit]During the Russo-Ukrainian war, a meme titled Battle of Techno House 2022, which features footage of a Russian soldier's failed effort at opening a door, went viral and was reposted millions of times.[12] Media coverage included discussion of an initial Wikipedia page for the incident/meme, which lampooned the event by using Wikipedia formatting generally used only for actual battles, making it seem like a real battle. The belligerents in the "battle" were humorously listed as "Russian Soldier" and "store door" with the battle results referred to as a "decisive door victory" and "pride" referred to as one of the Russian casualties.[13][14][15] The humorous content was later removed from the Wikipedia page.[16]

In fiction

[edit]The 2024 novel The Editors is centered around a group of editors of an online encyclopedia, Infopendium, based on Wikipedia.[17]

Contexts

[edit]Wikipedia is not always referenced in the same way. The ways described below are some of the ways it has been mentioned.

Citations of Wikipedia in culture

[edit]- People who are known to have used or recommended Wikipedia as a reference source include comedian Rosie O'Donnell,[18] and Rutgers University sociology professor Ted Goertzel.[19][20]

- Various people including Sir Ian McKellen,[21] Nicolas Cage,[22] and Marcus Brigstocke[23] have criticized or commented about Wikipedia's articles about themselves.

In politics

[edit]- In June 2011, Wikipedia received attention for attempts by editors to change the "Paul Revere" article to fit Sarah Palin's accounting of events during a campaign bus tour.[24][25] The New York Times reported that the article "had half a million page views" by June 10, and "after all the attention and arguments, the article is now much longer ... and much better sourced ... than before Palin's remarks."[26]

- In a speech given on October 28, 2013, to support Ken Cuccinelli for the candidacy of the governor of Virginia, Senator Rand Paul appeared to include close paraphrasing of the Wikipedia entry on the 1997 film Gattaca (version prior to speech) in his comments on eugenics, as noted by MSNBC host Rachel Maddow.[27][28]

- In April 2015, The Guardian reported claims that Grant Shapps, then-Chairman of the Conservative Party, or a person working under his orders, had edited Wikipedia pages about Shapps and other members of the British Parliament during the runup to the 2015 election, to which Shapps had denied involvement.[29]

- In October 2018, Jackson A. Cosko, a former staff member for US Senator Maggie Hassan, edited Wikipedia to dox several Congresspersons after being fired. Republican Senators Lindsey Graham, Orrin G. Hatch, Mitch McConnell, and Mike Lee had their personal addresses, cell phone numbers, and email addresses inserted into their respective wikipedia pages. The Senators were targeted for the role they played as Republican members of the Senate Judiciary Committee during the contentious Supreme Court nomination hearings of Brett Kavanaugh. [30] Cosko pleaded guilty in April 2019 and on 19 June 2019 was sentenced to four years in federal prison on five charges related to the event.[31]

- In February 2022, journalists at The Independent found that text from Wikipedia articles on Constantinople and the list of largest cities throughout history had been lifted by civil servants from the UK's Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities and placed verbatim into the government's Levelling Up White Paper.[32]

Wikipedia as comedic material

[edit]- Wikipedia is parodied at several websites, including Uncyclopedia[33][34] and Encyclopedia Dramatica.[35]

- In May 2006, British chat show host Paul O'Grady received an inquiry from a viewer regarding information given on his Wikipedia page, to which he responded, "Wikipedia? Sounds like a skin disease."

- Comedian Zach Galifianakis claimed to look himself up on Wikipedia in an interview with The Badger Herald,[36] stating about himself, "...I'm looking at Wikipedia right now. Half Greek, half redneck, around 6-foot-4. And that's about it... The 6-foot-4 thing may be a little bit off. Actually, it's 4-foot-6."

General information source

[edit]- Slate magazine compared Wikipedia to the fictional device The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy from the series of the same name by Douglas Adams. "The parallels between The Hitchhiker's Guide (as found in Adams' original BBC radio series and novels) and Wikipedia are so striking, it's a wonder that the author's rabid fans don't think he invented time travel. Since its editor was perennially out to lunch, the Guide was amended 'by any passing stranger who happened to wander into the empty offices on an afternoon and saw something worth doing.' This anonymous group effort ends up outselling Encyclopedia Galactica even though 'it has many omissions and contains much that is apocryphal, or at least wildly inaccurate.'"[37] This comparison of fictional documents in the series, is not unlike the mainstream comparisons between Wikipedia and professional Encyclopedias.[38]

As the basis of games

[edit]Redactle is a game in which the player must identify a Wikipedia article (chosen from the 10,000 vital articles) after it appears with most of its words redacted. Prepositions, articles, the verb "to be", punctuation and word lengths are shown. Players guess words, which are revealed if present in the article. As of June 2024[update] there have been over 800 daily games.[39][40][41]

Criticism

[edit]Claims of negative impact of Wikipedia on culture

[edit]Andrew Keen's 2007 book The Cult of the Amateur: How Today's Internet Is Killing Our Culture asserted the proliferation of user-generated content on Wikipedia obscured and devalued traditional, higher-quality information outlets.[42]

See also

[edit]- Truth in Numbers? Everything, According to Wikipedia, 2010 documentary

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Loxodonta", "African forest elephant", "African bush elephant", "Pachydermata", "Babar the Elephant", "Elephant", "Oregon",

"George Washington", "Latchkey kid", "Serial killer", "Hitler", "The Colbert Report" and "Stephen Colbert" are/were temporarily protected. "Mûmak" (formerly at "Oliphaunt") has also been vandalized.

References

[edit]- ^ Ablan, Jennifer (July 8, 2007). "Wikipedia page the latest status symbol". Reuters. Retrieved November 22, 2008.

- ^ The Colbert Report / Comedy Central recording Archived March 8, 2008, at the Wayback Machine of The WØRD "Wikiality", Comedy Central, July 31, 2006.

- ^ McCarthy, Caroline (August 1, 2006). "Colbert speaks, America follows: All Hail Wikiality!". c-net news.com.

- ^ "Colbert Causes Chaos on Wikipedia". Newsvine. August 1, 2006. Retrieved September 28, 2006.

- ^ "Poland to Honor Wikipedia With Monument". ABC News. October 9, 2014. Archived from the original on October 11, 2014. Retrieved October 9, 2014.

- ^ "World's first Wikipedia monument unveiled in Poland". thenews.pl. Archived from the original on October 25, 2014. Retrieved October 24, 2014.

- ^ Adams, Cameron (October 5, 2006). "Weird Al Yankovic". Herald Sun. Archived from the original on March 12, 2007.

- ^ Тюхтенко, Євгенія (January 18, 2016). Редактор української "Вікіпедії" створив для неї гімн. Радіо Свобода.

- ^ У МОН відбувся концерт з нагоди 15-ої річниці Вільної інтернет-енциклопедії Вікіпедія Archived January 28, 2016, at the Wayback Machine // Ministry of Education and science of Ukraine

- ^ ObsessiveMathsFreak (May 13, 2010). "Wikipedia Is Not Amused By Entry For xkcd-Coined Word". Slashdot. Archived from the original on October 1, 2018. Retrieved May 17, 2010.

- ^ McKean, Erin (May 30, 2010). "One-day wonder: How fast can a word become legit?". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on September 3, 2014. Retrieved May 10, 2014.

- ^ "Russian soldier's embarrassing 'loss' to locked door". PerthNow. March 3, 2022. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ^ Backhouse, Andrew (March 3, 2022). "Hapless Russian soldier loses fight against door". news.com.au. Retrieved May 5, 2023.

- ^ Rafter, Darcy (March 3, 2022). "Battle of Techno House memes spawn from hilarious Russian soldier vs door clip". HITC. Retrieved May 5, 2023.

- ^ "Video: Ruský vojak prehral boj s dverami". www.info.sk (in Slovak). March 3, 2022. Retrieved May 5, 2023.

- ^ "Wikipedia:Articles for deletion/Battle of Techno House 2022", Wikipedia, March 12, 2022, retrieved July 27, 2022

- ^ Caitlin Dewey (July 16, 2024). ""Wikipedia says no individual has a monopoly on truth": an interview with author Stephen Harrison". Yahoo! Life. Archived from the original on July 18, 2024. Retrieved July 18, 2024.

Harrison's forthcoming novel, "The Editors," is a timely techno-thriller based in its author's experience reporting on Wikipedia.

- ^ Hall, Sarah. "Rosie vs. Donald: She Said, He Said", E! Online, December 21, 2006

- ^ Skeptical Inquirer. Vol. 35 No. 3. Page 64

- ^ "The Conspiracy Meme", Skeptical Inquirer. Vol. 35 No. 1. January/February 2011. Page 37

- ^ "Lunch with Gandalf". Empire (203). May 2006. Archived from the original on April 5, 2006.(subscription required)

- ^ Nicolas Cage Answers the Web's Most Searched Questions | WIRED, April 21, 2022, retrieved April 24, 2022

- ^ Brew, Simon (March 23, 2009). "Marcus Brigstocke interview". DenOfGeek.com.

- ^ Lee Cowan (June 7, 2011). Wikipolitics: Palin fans try to rewrite history. NBC Nightly News with Brian Williams. NBC Universal. Archived from the original on August 8, 2013.

- ^ Brian Williams (June 6, 2011). Palin defends her telling of Revere's ride. NBC Nightly News with Brian Williams. NBC Universal. Archived from the original on July 19, 2013.

- ^ Cohen, Noam (June 12, 2011). "Shedding Hazy Light on a Midnight Ride". The New York Times. Retrieved August 1, 2011.

- ^ Strauss, Valerie (October 29, 2013). "Rand Paul does what gets kids in trouble: 'Borrow' from Wikipedia". The Washington Post. Retrieved October 29, 2013.

- ^ Maddow, Rachel (October 28, 2013). "Where'd you get your speech, Rand?". MSNBC. Archived from the original on October 30, 2013. Retrieved October 24, 2013.

- ^ "Election 2015: Grant Shapps denies Wikipedia claims". BBC. April 21, 2015. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- ^ Tully-McManus, Katherine (April 5, 2019). "Senate doxxing suspect pleads guilty, faces over 2 years in prison". The Hill. Retrieved April 5, 2019.

- ^ "District of Columbia | District Man Sentenced to Four Years for Stealing Senate Information and Illegally Posting Restricted Information of U.S. Senators on Wikipedia | United States Department of Justice". www.justice.gov. June 19, 2019. Retrieved October 16, 2024.

- ^ Stone, Jon (February 3, 2022). "Parts of Michael Gove's levelling-up plan 'copied from Wikipedia'". The Independent. Retrieved February 3, 2022.

- ^ "The brains behind Uncyclopedia". .net. May 3, 2007. Retrieved November 19, 2007.

- ^ "Online parody of Tucson not always funny, but interesting". Arizona Daily Star. August 18, 2006. Archived from the original on August 22, 2006. Retrieved August 22, 2006.

- ^ Dee, Jonathan (July 1, 2007). "Wikipedia". New York Times Magazine. Retrieved November 19, 2007.

- ^ "The Badger Herald". 2007. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved March 22, 2007.

- ^ Boutin, Paul (May 3, 2005). "Wikipedia is a real-life Hitchhiker's Guide". Slate Magazine.

- ^ Silverman, Matt (March 16, 2012). "Encyclopedia Britannica vs. Wikipedia [INFOGRAPHIC]". Mashable.

- ^ Livingston, Christopher (April 20, 2022). "Redactle is a brutal spin on Wordle that may take you hundreds of guesses". PC Gamer. Retrieved June 18, 2024.

- ^ Skwarecki, Beth (May 23, 2024). "14 of the Best Wordle Variants You Should Play". Lifehacker. Retrieved June 18, 2024.

- ^ "About". Redactle. Retrieved June 18, 2024.

- ^ Kakutani, Michiko (July 27, 2008). "The Cult of the Amateur (book review)". New York Times. Retrieved July 8, 2008.