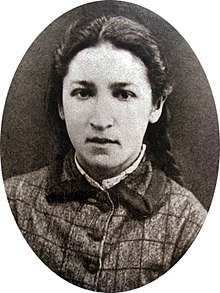

Vera Zasulich

Vera Zasulich | |

|---|---|

Вера Засулич | |

Vera Ivanovna Zasulich | |

| Born | 8 August 1849 |

| Died | 8 May 1919 (aged 69) |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Political party | Mensheviks |

Vera Ivanovna Zasulich (Вера Ивановна Засулич; 8 August [O.S. 27 July] 1849 – 8 May 1919) was a Russian socialist activist, Menshevik writer and revolutionary.[1] She is widely known for her correspondence with Karl Marx, in which she put into question the necessity of a capitalist industrialisation prior to socialism, in the context of the fact that there already were living farmer communities in Russia that had developed practices and cultures that had a communist component.[2]

Radical beginnings

[edit]Zasulich was born in Mikhaylovka, in the Smolensk Governorate of the Russian Empire, as one of four daughters of an impoverished minor Polish nobleman. When she was three years old, her father died and her mother sent her to live with her wealthier relatives, the Mikulich family, in Byakolovo. After graduating from high school in 1866, she moved to Saint Petersburg, where she worked as a clerk. Soon she became involved in radical politics and taught literacy classes for factory workers. Her contacts with the Russian revolutionary leader Sergei Nechaev led to her arrest and imprisonment in 1869.[3]

After Zasulich was released in 1873, she settled in Kiev, where she joined the Kievan Insurgents, a revolutionary group of Mikhail Bakunin's anarchist supporters, and became a respected leader of the movement. As her lifelong friend and fellow revolutionary Lev Deich wrote:

- "Because of her intellectual development, and particularly she was so well read, Vera Zasulich was more advanced than the other members of the circle.... Anyone could see that she was a remarkable young woman. You were struck by her behavior, particularly by the extraordinary sincerity and unaffectedness of her relations with others."[4]

Trepov incident

[edit]In July 1877, a political prisoner, Arkhip Bogolyubov, refused to remove his cap in the presence of Colonel Fyodor Trepov, the governor of St. Petersburg famous for his suppression of the Polish rebellions in 1830 and 1863. In retaliation, Trepov ordered Bogolyubov to be flogged, which outraged not only revolutionaries but also sympathetic members of the intelligentsia. A group of six revolutionaries plotted to kill Trepov, but Zasulich was the first to act. She and her fellow social revolutionary, Maria (Masha) Kolenkina, were planning to shoot two government representatives: the prosecutor Vladislav Zhelekhovskii in the Trial of the 193 and another enemy of the populist movement.[5] Following the Bogolyubov flogging, they decided that the second target should be Trepov.[6] Waiting until after the verdict was announced at the Trial of 193, on 24 January 1878 they went for their respective targets. Kolenkina's attempt against Zhelekhovskii failed, but Zasulich used a British Bulldog revolver and shot and seriously wounded Trepov.[7]

At her widely publicized trial, presided over by the prominent liberal judge Anatoly Koni, the sympathetic jury found Zasulich not guilty, an outcome that tested the effectiveness of the judicial reform of Alexander II. On one interpretation, it demonstrated the courts' ability to stand up to the authorities. However, Zasulich also had a very good lawyer, who turned the case on its head so that it "very soon became obvious that it was Colonel Trepov rather than his would-be assassin who was really being tried".[8] That Trepov and the government now appeared as the guilty party demonstrated the ineffectiveness of both the courts and the government.[9]

Fleeing before she could be rearrested and retried, Zasulich became a hero to populists and the radical part of the Russian society. Despite her previous record, she was against the terror campaign that would eventually lead to the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881.[10]

Move to Marxism

[edit]After the trial had been annulled, Zasulich fled to Switzerland, where she became a Marxist and co-founded the Emancipation of Labour group with Georgi Plekhanov and Pavel Axelrod in 1883. The group commissioned Zasulich to translate a number of Karl Marx's works into Russian, which contributed to the growth of Marxist influence among Russian intellectuals in the 1880s and 1890s and was one of the factors that led to the creation of the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party (RSDLP) in 1898. In mid-1900, the leaders of the radical wing of the new generation of Russian Marxists, Julius Martov, Vladimir Lenin, and Alexander Potresov, joined Zasulich, Plekhanov, and Axelrod in Switzerland. In spite of the tensions between the two groups, the six founded Iskra ("Spark" in English), a revolutionary Marxist newspaper, and formed its editorial board. They were opposed to the more moderate Russian Marxists (known as "economists") as well as ex-Marxists like Peter Struve and Sergei Bulgakov and spent much of 1900–1903 debating them in Iskra.

Menshevik leader

[edit]The Iskra editors were successful in convening a pro-Iskra Second Congress of the RSDLP in Brussels and London in 1903. However, Iskra supporters unexpectedly split during the Congress and formed two factions, Lenin's Bolsheviks and Martov's Mensheviks, Zasulich siding with the latter. She returned to Russia after the 1905 Revolution, but her interest in revolutionary politics waned. She entered the independent Yedinstvo-faction of her old friend Plekhanov[11] in early 1914. As a member of this small faction, Zasulich supported the Russian war effort during World War I, whereas the Bolsheviks opposed the war.[12] She opposed the October Revolution of 1917, stating that a "premature revolution" was "worse than no revolution at all".[13] In the winter of 1919, a fire broke out in her room. She was accommodated by two sisters who lived in the same courtyard, but she developed pneumonia and died in Petrograd on 8 May 1919.

In his book Lenin, Leon Trotsky, who was friendly with Zasulich in London in 1900, wrote:

Zasulich was a curious person and a curiously attractive one. She wrote very slowly and suffered actual tortures of creation... "Vera Ivanovna does not write, she puts mosaic together, Vladimir Ilyich [Lenin] said to me at that time", and in fact she put down each sentence separately, walked up and down the room slowly, shuffled about in her slippers, smoked constantly hand-made cigarettes and threw the stubs and half-smoked cigarettes in every direction on all the window seats and tables, and scattered ashes over her jacket, hands, manuscripts, tea in the glass, and incidentally her visitor. She remained to the end the old radical intellectual on whom fate grafted Marxism. Zasulich's articles show that she had adopted to a remarkable degree the theoretic elements of Marxism. But the moral political foundations of the Russian radicals of the '70s remained untouched in her until her death.[14]

See also

[edit]- Nihilist movement

- Vera; or, The Nihilists. This was the first play by Irish writer Oscar Wilde, which is said to be loosely inspired by the life of Vera Zasulich. Though none of Wilde's characters correspond to actual Russian people of the time, it has been suggested that the plot was inspired by Vera's shooting of Trepov. The play was published in 1880 and first performed in New York in 1883.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Queen of the Neighbourhood; Queen of the Neighbourhood Collective (2010). Revolutionary Women: A Book of Stencils. PM Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-60486-200-3. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- ^ "Marx-Zasulich Correspondence 1881". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 31 January 2024.

- ^ Noonan, N.C.; Nechemias, N.C.N.C.; Nechemias, C. (2001). Encyclopedia of Russian Women's Movements. ABC-Clio ebook. Greenwood Press. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-313-30438-5. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- ^ Lev Deich. "Yuzhnye buntari" in Golos Minuvshego, Vol. 9, p.54. Quoted in Five Sisters: Women Against the Tsar, eds. Barbara A. Engel, Clifford N. Rosenthal, Routledge, 1975, reprinted in 1992, ISBN 0-415-90715-2, pp.61–62.

- ^ Peter Kropotkin (1 January 1905). "The Constitutional Movement in Russia". revoltlib.com. The Nineteenth Century.

- ^ Barbara A. Engel and Clifford N. Rosenthal "Five Sisters: Women Against the Tsar" (1975), p.61.

- ^ Ana Siljak, Angel of Vengeance: the "Girl Assassin," the Governor of St. Petersburg, and Russia's Revolutionary World (2008), p. 2, 10–11.

- ^ Adam B. Ulam, In the Name of the People: Prophets and Conspirators in Prerevolutionary Russia (1977)

- ^ Rapoport, D.C. (2006). Terrorism: The first or anarchist wave. Critical concepts in political science. Routledge. p. 215. ISBN 978-0-415-31651-4. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- ^ Viti͡u͡k, V.V. (1985). Leftist terrorism. Progress Publishers. p. 9. ISBN 9780828530200. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

Let us turn to numerous articles by Georgi Plekhanov and Vera Zasulich, and to a special resolution adopted by the Second ... "The exact reason why we are against terrorism is that it is not revolutionary"— thus Zasulich expressed the general ...

- ^ See Leopold H. Haimson. The Making of Three Russian Revolutionaries, Cambridge University Press, 1987, ISBN 0-521-26325-5, p.472, note 6.

- ^ Pipes, Richard (2010). "The Trial of Vera Z." Russian History. 37 (1): v–82. JSTOR 24664570. Retrieved 5 May 2024.

- ^ Bergman, Jay (1979). "The Political Thought of Vera Zasulich". Slavic Review. 38 (2): 257–258. doi:10.2307/2497085. JSTOR 2497085. Retrieved 5 May 2024.

- ^ Leon Trotsky: Lenin, New York, Blue Ribbon Books, 1925, chapter "Lenin and the Old Iskra"

References

[edit]- Jay Bergman. Vera Zasulich: A Biography, Stanford University Press, 1983, ISBN 0-8047-1156-9, 261p.

- Ana Siljak. Angel of Vengeance: The "Girl Assassin," the Governor of St. Petersburg, and Russia's Revolutionary World, St. Martin's Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0-312-36399-4, 370p.

- Barbara Alpern Engel & Clifford N. Rosenthal (eds.) Five Sisters: Women Against the Tsar, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1976, reprinted in 1992, ISBN 0-415-90715-2, pp. 61–62.

External links

[edit] Media related to Vera Zasulich at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Vera Zasulich at Wikimedia Commons- Marxists.org Vera Zasulich Archive

- Vera Zasulich Anarchist Encyclopedia

- "Lenin" by Leon Trotsky

- The Trial of Vera Z., by Richard Pipes

- 'Women and Terror' – interview with Dr. Mia Bloom