Caxton Hall

| Caxton Hall | |

|---|---|

Caxton Hall | |

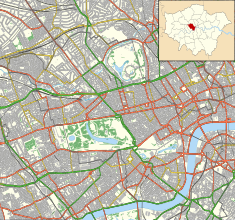

| Location | Caxton Street, Westminster |

| Coordinates | 51°29′55″N 0°8′6.5″W / 51.49861°N 0.135139°W |

| Built | 1883 |

| Architect | William Lee and F.J. Smith |

| Architectural style(s) | Francois I style |

Listed Building – Grade II | |

| Designated | 15 March 1984 |

| Reference no. | 1357266 |

Caxton Hall is a building on the corner of Caxton Street and Palmer Street, in Westminster, London, England. It is a Grade II listed building primarily noted for its historical associations. It hosted many mainstream and fringe political and artistic events and after the Second World War was the most popular register office used by high society and celebrities who required a civil marriage.

History of the structure

[edit]Following a design competition set by the parishes of St Margaret and St John,[1] the chosen design was a proposal by William Lee and F.J. Smith in an ornate Francois I style using red brick and pink sandstone, with slate roofs.[2] The foundation stone was laid by the philanthropist, Baroness Burdett-Coutts, on 29 March 1882.[3] The facility, which contained two public halls known as the Great and York Halls, was opened as "Westminster Town Hall" in 1883.[4]

The building ceased to be the local seat of government after the creation of the enlarged City of Westminster in 1900.[5] It was renamed Caxton Hall at that time to commemorate the printer, William Caxton,[5] who had worked in the almonry of Westminster Abbey.[6]

However the halls continued to be used for a variety of purposes including public meetings and musical concerts.[7] A central entrance porch and canopy were added in the mid-20th century, now removed.[2]

From 1933 on it was used as a Central London register office and was the venue for many celebrity weddings. This function closed in 1979 and the building stood empty for years getting a place on the Buildings at Risk Register.[1] It was listed as a building of Special Architectural or Historic Interest on 15 March 1984.[2] It was redeveloped as apartments and offices in 2006. The facade and former register office at the front of the building facing Caxton Street were restored and retained being converted into luxury flats (see Facadism). The rear of the building, containing the halls, was demolished and a circular office building, named the Asticus Building, was built on the site.[4]

History of its social and political use

[edit]The building was the location of the First Pan-African Conference in 1900.[8]

The Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), part of the British Suffragette movement, held a 'Women's Parliament' at Caxton Hall at the beginning of each parliamentary session from 1907, with a subsequent procession to the Houses of Parliament and an attempt (always unsuccessful) to deliver a petition to the prime minister in person.[1] Caxton Hall's central role in the militant suffrage movement is now commemorated by a bronzed scroll sculpture that stands nearby in Christchurch Gardens open space.[9]

In 1910 the occultist Aleister Crowley staged his Rites of Eleusis at Caxton Hall. The series of performances took place over six weeks, and received mixed reviews.[10]

In January 1918 Prime Minister David Lloyd George outlined the main war goals of the Allies.[11]

During the Second World War it was used by the Ministry of Information as a venue for press conferences held by Winston Churchill and his ministers. This wartime role is marked by a commemorative plaque unveiled in 1991.[12]

In 1940, Indian nationalist Udham Singh assassinated Irish colonial administrator Michael O'Dwyer at Caxton Hall, where O'Dwyer was giving a speech. At the end of the speech, Singh walked towards O'Dwyer and fatally shot him. Singh's motivations for the assassination were O'Dwyer's actions during the Indian independence movement in the Punjab Province, where he played a role in the 1919 Jallianwala Bagh massacre (of which Singh was a survivor) and ordered several crackdown against anti-colonial demonstrators.[13][1]

The Caxton Hall was the location of the press conference that the Russell–Einstein Manifesto was released in 1955 in response to the threat of nuclear war and humanity destroying itself.[14]

On 12 May 1960, over 1,000 people attended the first public meeting of the Homosexual Law Reform Society.[15]

The National Front was formed at a meeting in Caxton Hall, Westminster on 7 February 1967.[16]

It was also used as a central London register office for weddings from October 1933 to 1978.[17] On 18 August 1952, future Prime Minister Anthony Eden married Clarissa Spencer-Churchill, the niece of the then Prime Minister Winston Churchill.[1][18] Other notable people who were married there include; Donald Campbell, Elizabeth Taylor, Roger Moore, Adam Faith, Joan Collins, Peter Sellers, Yehudi Menuhin, and Ringo Starr.[1][19]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Hibbert, Christopher; Ben Weinreb; John Keay; Julia Keay; Matthew Weinreb (2009). "Caxton Hall". The London Encyclopaedia. Macmillan. ISBN 978-1405049252.

- ^ a b c Historic England. "Caxton Hall (1357266)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ "Caxton Hall - foundation stone". London Remembers. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- ^ a b GLA planning report PDU/0583/01 Archived 17 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine 2003

- ^ a b "London's Town Halls". Historic England. p. 204. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ Timbs, John (1855). Curiosities of London: Exhibiting the Most Rare and Remarkable Objects of Interest in the Metropolis. D. Bogue. p. 4.

- ^ "Programme of concert held at Caxton Hall to commemorate the 25th anniversary of Pepys House". National Archives. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ Lawrence, Michael Anthony (22 November 2010). Radicals in their Own Time: Four Hundred Years of Struggle for Liberty and Equal Justice in America. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1139494076.

- ^ Crawford, Elizabeth (2001). The women's suffrage movement: a reference guide, 1866–1928. p. 262. ISBN 978-0415239264.

- ^ Churton, Tobias (2012). Aleister Crowley: The Biography - Spiritual Revolutionary, Romantic Explorer, Occult Master and Spy. Watkins Media Limited. ISBN 9781780283845.

- ^ Alan Sharp, "From Caxton Hall to Genoa via Fontainebleau and Cannes: David Lloyd George’s Vision of Post-War Europe." in Aspects of British Policy and the Treaty of Versailles (Routledge, 2020) pp. 121-142. online

- ^ "City of Westminster green plaques". Archived from the original on 16 July 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2011.

- ^ Nigel Collett, The Butcher of Amritsar (2006), pp. 246–247

- ^ Rotblat, Joseph (1982). Proceedings of the first Pugwash Conference on Science and World Affairs. London: Pugwash Council. p. 6. OCLC 934755212.

- ^ "Homosexual Law Reform Society Pamphlet". UK Parliament. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ Cumming, Ed (7 November 2011). "Caxton Hall: A pied-à-terre with a rich history". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 7 November 2011.

- ^ "Locations of Westminster registration records". Westminster City Council. 24 January 2014. Archived from the original on 4 December 2023. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- ^ Mr. Eden weds niece of the Prime Minister ITN News, 18 August 1952. Accessed July 2011

- ^ MoLAS 2004 Report Archived 12 September 2012 at archive.today Museum of London Archaeology, Caxton Hall, March 2004 . Accessed July 2011

External links

[edit]- Caxton Hall in Westminster and the marriage of Diana Dors to Dennis Hamilton Another Nickel in the Machine. Accessed July 2011. Many pictures of Caxton Hall events.