Classical education in the Western world

Classical education in the Western world refers to a long-standing tradition of pedagogy that traces its roots back to ancient Greece and Rome, where the foundations of Western intellectual and cultural life were laid. At its core, classical education is centered on the study of the liberal arts, which historically comprised the trivium (grammar, rhetoric, and logic) and the quadrivium (arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy). This educational model aimed to cultivate well-rounded individuals equipped with the knowledge and skills necessary to engage in public life, think critically, and pursue moral and intellectual virtues.[1]

In ancient Greece, the classical curriculum emerged from the educational practices of philosophers like Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, who emphasized dialectical reasoning and the pursuit of truth.[2] The Roman Empire adopted and adapted these Greek educational ideals, placing a strong emphasis on rhetoric and the development of oratory skills, which were considered essential for participation in civic life.[3] As these classical ideas were preserved and transmitted through the Middle Ages, they became the foundation for the educational systems that emerged in Europe, particularly within monastic and cathedral schools.[4]

The Renaissance marked a significant revival of classical education, as scholars in Europe rediscovered and embraced the texts and ideas of antiquity. Humanists of this period championed the study of classical languages, literature, and philosophy, seeing them as essential for cultivating a virtuous and knowledgeable citizenry. This revival continued into the Age of Enlightenment, where classical education played a central role in shaping the intellectual movements that emphasized reason, individualism, and secularism.[5]

Despite undergoing significant transformations over the centuries, classical education has maintained a lasting influence on Western thought and educational practices. Today, its legacy can be seen in the curricula of liberal arts colleges, the resurgence of classical Christian education, and ongoing debates about the relevance of classical studies in a modern, globalized world.[4]

Origins in ancient Greece

[edit]Education in ancient Greece laid the foundation for what would later be recognized as the classical education tradition in the Western world. The educational systems in ancient Greece were diverse, reflecting the different needs and values of the various city-states. In Sparta, education was highly militaristic, designed to produce disciplined and physically strong warriors. From a young age, Spartan boys underwent rigorous training, emphasizing endurance, obedience, and martial skills, which were essential to maintaining Sparta's military dominance.[6]

In contrast, Athenian education was more holistic, aiming to cultivate well-rounded individuals who could contribute to civic life. Athenian education emphasized intellectual development alongside physical training, with a strong focus on the arts, philosophy, and rhetoric. This system was designed to prepare young men for active participation in the democratic processes of the city-state. The concept of paideia, central to Athenian education, involved the comprehensive development of a person's intellectual, moral, and physical capacities, which was seen as essential for creating ideal citizens.[7]

Philosophers like Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle played crucial roles in shaping the educational ideals of Athens. Socrates introduced the dialectical method, a form of questioning that encouraged critical thinking and self-reflection, which became a cornerstone of Western educational thought. Plato, through his Academy, emphasized the importance of philosophical education as a means to achieve moral and intellectual excellence. Aristotle, in turn, founded the Lyceum, where he advanced the study of logic, ethics, and natural sciences, laying the groundwork for many disciplines that would later become central to Western education.[8]

The Athenian model of education, with its emphasis on the development of both the mind and body, became the archetype for classical education in the Western world. This model was not only influential in ancient Greece but also served as the foundation for educational systems in later Western societies. The blend of intellectual rigor, moral education, and physical training established in ancient Athens continues to be a reference point for discussions on the purposes and methods of education.[9]

Roman contributions

[edit]

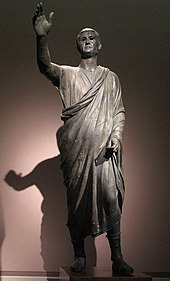

Roman education played a crucial role in shaping the classical education tradition in the Western world, particularly through its emphasis on rhetoric, law, and civic duty. Unlike the more diverse educational systems of ancient Greece, Roman education was more uniform, reflecting the centralization of Roman society and its focus on preparing citizens for public life. The Roman educational system was heavily influenced by Greek models, especially in its later stages, but it adapted these influences to fit the needs of Roman culture and governance.[10]

Education in Rome was primarily divided into three stages: elementary, secondary, and rhetorical. The elementary stage focused on basic literacy, numeracy, and moral education, often delivered by a ludi magister or elementary teacher. Roman children, regardless of social class, were expected to learn reading, writing, and arithmetic, which were considered essential for participating in Roman society. This foundational education was not only for free citizens but, in some cases, was extended to slaves, particularly those who were expected to perform administrative duties for their masters.[11]

As students progressed to the secondary level, the focus shifted to the study of Latin literature and grammar, which were seen as crucial for understanding and interpreting Roman law, history, and culture. The study of Latin texts, such as the works of Virgil and Cicero, was central to this stage, with teachers using these texts to teach both language and moral lessons. The creation and circulation of teaching materials, such as textbooks and commentaries, played a significant role in standardizing the curriculum and ensuring that students across the empire received a similar education.[12]

The final stage of Roman education was rhetorical training, which was essential for those pursuing careers in law, politics, or public speaking. Roman rhetorical education emphasized the art of persuasion and the development of oratory skills, which were considered the highest form of intellectual achievement. This stage was often guided by experienced rhetoricians who taught students the techniques of argumentation, speech composition, and delivery. The bond between teacher and student in these rhetorical schools was often close and enduring, reflecting the importance of personal mentorship in Roman education.[13]

Roman education was not limited to men; women also had access to education, though it was generally less formal and focused more on domestic skills. However, women from elite families sometimes received an education that included literature and rhetoric, preparing them for roles in managing estates or participating in intellectual life. The role of education in improving the social and legal status of women in Roman society is a topic of ongoing scholarly interest.[14]

Medieval scholasticism

[edit]

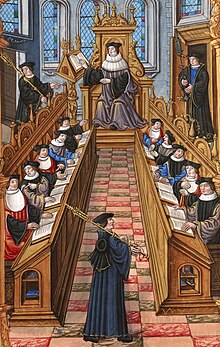

The rise of universities in medieval Europe marked a significant development in the history of classical education, transforming the intellectual landscape and laying the foundation for modern higher education. Medieval universities emerged from the earlier cathedral and monastic schools, which had been the primary centers of learning in the early Middle Ages. These universities, first established in the 11th and 12th centuries, became the principal institutions for advanced study, particularly in the fields of theology, law, medicine, and the arts.[15]

The earliest universities, such as the University of Bologna, the University of Paris, and the University of Oxford, were largely self-governing institutions, operating under charters granted by secular or religious authorities. They were organized into faculties, each responsible for a specific area of study, with students progressing through a structured curriculum that culminated in the awarding of degrees. The studium generale, or general study, was a key feature of these institutions, indicating their status as centers of learning that attracted students from across Europe.[16]

The curriculum at medieval universities was heavily influenced by classical education, particularly the study of the liberal arts, which were divided into the trivium (grammar, rhetoric, and logic) and the quadrivium (arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy). These subjects provided the foundation for more advanced studies in theology, law, and medicine. Latin was the language of instruction, and the teaching method was predominantly based on lectures and disputations, where students engaged in formal debates to develop their rhetorical and analytical skills.[17]

Life at medieval universities was often challenging, with students facing a demanding academic schedule, financial difficulties, and sometimes harsh living conditions. Despite these challenges, universities became vibrant centers of intellectual and social activity, with students and scholars forming a distinct community. The universities' influence extended beyond education, as they played a crucial role in shaping European intellectual life and contributed to the cultural and political developments of the Middle Ages.[18]

Renaissance humanism

[edit]

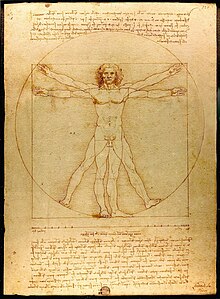

The Renaissance, beginning in the 14th century, marked a profound revival of classical learning and values, driven largely by the humanist movement. This intellectual revolution sought to rediscover and reintegrate the literature, philosophy, and educational ideals of ancient Greece and Rome into the fabric of European culture. At the heart of this movement was the studia humanitatis, a curriculum that emphasized the study of grammar, rhetoric, history, poetry, and moral philosophy—disciplines seen as essential for the development of virtuous and well-rounded individuals.[19]

Humanism played a central role in reshaping the educational landscape of the Renaissance. Humanists like Petrarch and Erasmus advocated for the study of classical texts not merely as a means of scholarly inquiry but as a way to cultivate moral and civic virtues. This approach to education sought to create citizens who were not only knowledgeable but also ethically grounded and capable of contributing to the public good.[20] The revival of classical languages, particularly Latin and Greek, was central to this humanist education, as these languages were seen as the key to unlocking the wisdom of the ancients.

The humanist educational program expanded the traditional medieval curriculum, which had been dominated by the trivium (grammar, rhetoric, logic) and quadrivium (arithmetic, geometry, music, astronomy). Humanists redefined the trivium to place greater emphasis on rhetoric and moral philosophy, while also incorporating history and poetry as essential components of a well-rounded education. This curriculum, known as the studia humanitatis, became the foundation of humanist education and was widely adopted in universities and schools across Europe.[21]

Renaissance humanism also had a significant institutional impact, as it led to the establishment of new educational institutions and the transformation of existing ones. Universities and academies across Europe began to incorporate humanist principles into their curricula, fostering an environment where classical education could thrive. This shift not only affected the content of education but also its purpose, as education came to be seen as a means of shaping both the mind and character of individuals.[22]

The legacy of Renaissance humanism in education is profound, as it laid the groundwork for modern liberal arts education. The humanist emphasis on critical thinking, moral education, and the study of classical texts has continued to influence educational theory and practice up to the present day. The Renaissance humanists' reimagining of classical education ensured that the wisdom of the ancient world remained a vital part of Western intellectual life, shaping the development of education for centuries to come.[23]

Age of Enlightenment

[edit]

The Age of Enlightenment, spanning the 17th and 18th centuries, marked a shift in the history of education, as intellectual currents of the time emphasized reason, science, and secularism. This period saw the gradual decline of religious control over educational institutions and the rise of secular education systems that prioritized empirical knowledge and critical thinking. The Enlightenment thinkers believed that education was essential for the progress of society and the cultivation of informed citizens capable of contributing to public life.[25]

In France, the Enlightenment had a profound impact on higher education. Universities, previously dominated by religious instruction, began to incorporate more secular subjects such as natural sciences, philosophy, and modern languages into their curricula. The French state, influenced by Enlightenment ideals, increasingly took control of educational institutions, promoting a curriculum that aligned with rationalist and secular values. This shift was particularly evident in the reformation of French universities and the establishment of new schools that focused on practical and scientific knowledge.[26]

In England, the Enlightenment contributed to the development of a more inclusive educational system. The spread of literacy and the growth of public education were driven by Enlightenment ideals that emphasized the importance of education for all citizens, not just the elite. This period also saw the establishment of new educational institutions, including schools and academies, which offered instruction in a range of subjects beyond the traditional classical curriculum. These developments laid the groundwork for the expansion of popular education in the 19th century.[27]

The Enlightenment also fostered the rise of public spheres where education, particularly secular education, played a crucial role. Intellectuals like Voltaire and Rousseau argued for educational reforms that would free learning from ecclesiastical control and make it accessible to a broader segment of society. The growth of literacy, the establishment of libraries, and the creation of educational societies were all part of this broader movement toward secular and public education. These changes reflected a fundamental shift in how education was perceived—as a tool for personal and societal advancement rather than merely a means of religious instruction.[28]

19th and 20th century developments

[edit]The 19th and 20th centuries witnessed a significant decline in classical education. During this period, classical education, which had dominated European and American schools and universities, faced challenges from various educational reforms that sought to modernize curricula and make education more accessible and practical for a broader population.

In the 19th century, the classical model of education began to wane as industrialization and scientific advancements demanded a more specialized and utilitarian approach to education. Educational reformers, particularly in Europe and the United States, advocated for curricula that emphasized the natural sciences, mathematics, and modern languages over the traditional focus on Latin, Greek, and classical literature. Despite these changes, classical education retained its influence, especially in elite institutions, where it continued to be seen as a foundation for developing critical thinking, moral reasoning, and leadership qualities.[29]

As the 20th century progressed, the shift toward progressive education, influenced by figures such as John Dewey, further marginalized classical education. Progressive education emphasized experiential learning, critical thinking, and social engagement over the rote memorization and strict discipline associated with traditional classical education. However, the core principles of classical education—especially the value of studying great books and the liberal arts—remained influential in certain academic and intellectual circles, particularly within liberal arts colleges and universities.[30]

Mortimer Adler's work in the mid-20th century, particularly through the Great Books movement, sought to reestablish the study of classic texts as central to a well-rounded education. Adler argued that the great books of Western civilization offered timeless insights into the human condition and should be made accessible to all students, not just the elite. His efforts helped to preserve the legacy of classical education and inspired a renewed interest in the liberal arts during the latter half of the century.[31]

Another significant figure in the mid-20th century revival of classical education was Dorothy Sayers, whose 1947 essay, The Lost Tools of Learning, argued for a return to the medieval trivium as a method for teaching children how to think rather than merely what to think. Sayers' work became a cornerstone for the later revival of classical education, particularly within the Christian education movement. Sayers proposed that the trivium—comprising grammar, logic, and rhetoric—should be taught in a manner that corresponds with the natural stages of a child's cognitive development.[32]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2024) |

Classical education movement

[edit]In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, classical education experienced a resurgence, particularly within the Christian education movement in the United States. Schools and homeschool programs began to adopt curricula based on the classical model, emphasizing the trivium and quadrivium as foundational to a well-rounded education. This revival was driven by a desire to return to an educational system that prioritizes wisdom, virtue, and the cultivation of the whole person over mere vocational training.

Kevin Clark and Ravi Jain's book, The Liberal Arts Tradition: A Philosophy of Christian Classical Education, has been instrumental in articulating the philosophy behind this modern classical education movement. They argue for a return to a holistic education that integrates faith, reason, and the classical liberal arts to form individuals who can think critically and act ethically in the world. Their work reflects the ongoing influence of classical education principles in shaping contemporary educational practices.[30]

The resurgence of classical education is also reflected in the growth of institutions dedicated to this educational philosophy, such as Hillsdale College and various charter schools across the United States. These institutions have played a significant role in promoting classical education as a viable and desirable alternative to mainstream educational models. The movement has gained traction among parents and educators who are disillusioned with modern educational trends and seek to provide a more rigorous and morally grounded education for their children.[29]

Impact and legacy

[edit]Classical education has left an indelible mark on Western culture, shaping the intellectual, cultural, and educational landscapes of Europe and the Americas for centuries. Its influence can be traced from the Renaissance through to modern times, with its principles continuing to inform contemporary educational practices.

The revival of classical learning during the Renaissance had a profound impact on European intellectual life. Humanist scholars like Petrarch and Erasmus reintroduced the works of ancient Greek and Roman authors, embedding classical texts into the curricula of universities and schools. This emphasis on the studia humanitatis, or the study of humanity through literature, history, and moral philosophy, laid the foundation for what we now consider the liberal arts. The Renaissance not only revived classical texts but also reinvigorated the methods of critical thinking, analysis, and rhetoric that are central to classical education.[33]

The impact of classical education is also evident in the development of modern liberal arts education. The idea that education should cultivate wisdom, virtue, and a broad understanding of human knowledge is deeply rooted in the classical tradition. This legacy is particularly strong in institutions like liberal arts colleges, where the curriculum often reflects the holistic approach of classical education, integrating the study of literature, philosophy, history, and the sciences.[34]

Moreover, classical education has influenced not only the content of education but also its purpose. The Renaissance humanists believed that education should prepare individuals for public life and civic responsibility, a belief that has persisted in various forms throughout Western educational history. The classical emphasis on rhetoric and moral philosophy has informed the development of educational systems that prioritize the formation of ethical and informed citizens.[35]

In the broader cultural context, the legacy of classical education extends beyond the classroom. It has shaped Western literature, art, and philosophy, providing a framework for exploring and expressing the complexities of the human experience. The works of Homer, Virgil, and Plato, among others, have inspired countless generations of artists, writers, and thinkers, ensuring that classical ideas remain a vital part of Western cultural identity.[36]

Classical education's impact is also global, having been spread through colonialism and globalization. Western educational models, including those based on classical principles, were introduced to other parts of the world, influencing educational systems far beyond Europe and the Americas. This global influence underscores the enduring power of classical education to shape minds and societies across different cultures and historical periods.[37]

See also

[edit]- Ijazah, a license particularly associated with transmission of Islamic religious knowledge

- Imperial examination, a civil service examination system in Imperial China

- Madrasa, usually a specific type of religious school or college

- Scholar-official, government officials and prestigious scholars in Chinese society

References

[edit]- ^ Grendler (2004); Dawson (2010).

- ^ Jaeger (1986).

- ^ Quintilian (1920).

- ^ a b Dawson (2010).

- ^ Grendler (2004).

- ^ Pomeroy (2002); Adkins & Adkins (2005).

- ^ Marrou (1956); Downey (1957).

- ^ Marrou (1956); Sienkewicz (2007).

- ^ Mavrogenes (1980); Sienkewicz (2007).

- ^ Bonner (1977); Bloomer (2011).

- ^ Turner (1951); Booth (1979).

- ^ Starr (1987); Dickey (2010).

- ^ Gwynn (1926); Richlin (2011).

- ^ Bowman & Woolf (1994); Van den Bergh (2000).

- ^ Rashdall (1987); De Ridder-Symoens (1992).

- ^ Pedersen (1997); Ferruolo (1998).

- ^ Haskins (1972); Cobban (1999).

- ^ Rait (1931); Thorndike (1975).

- ^ Bolgar (1954); Kristeller (1979).

- ^ Garin (1965); Celenza (2004).

- ^ Kraye (1996); Nauert (2006).

- ^ Cassirer, Kristeller & Randall (1969); Grafton (1987).

- ^ Bolgar (1954); Celenza (2004).

- ^ Culture: Nine European historical sites now on the European Heritage Label list European Commission, February 8, 2016

- ^ Cubberley (1920); Butts (1955).

- ^ Ringer (1979); Brockliss (1987).

- ^ Wardle (1970); Lawson & Silver (2013).

- ^ Graff (1987); Melton (2001).

- ^ a b Unger (2007).

- ^ a b Clark & Jain (2013).

- ^ Adler (2000).

- ^ Sayers (1948).

- ^ Bolgar (1954); Nauert (2006).

- ^ Grafton (1987); Kimball (1995).

- ^ Curtius (1973); Winterer (2002).

- ^ Barzun (2000).

- ^ Grafton (1987).

Works cited

[edit]This article lacks ISBNs for the books listed. (August 2024) |

- Adkins, Lesley; Adkins, Roy A. (2005). Handbook to Life in Ancient Greece. New York: Facts On File. ISBN 978-0816056590.

- Adler, Mortimer Jerome (2000). Weismann, Max (ed.). How to Think about the Great Ideas: From the Great Books of Western Civilization. Chicago: Open Court. ISBN 978-0-8126-9693-6. OCLC 680284007.

- Barzun, Jacques (2000). From Dawn to Decadence: 500 Years of Western Cultural Life, 1500 to the Present. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-017586-3.

- Bloomer, W. Martin (2011). The School of Rome: Latin Studies and the Origins of Liberal Education. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520255760.

- Bolgar, R. R. (1954). The Classical Heritage and Its Beneficiaries: from the Carolingian Age to the End of the Renaissance. Cambridge. ISBN 978-0521098120.

- Bonner, Stanley F. (1977). Education in Ancient Rome: From the Elder Cato to the Younger Pliny. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0520034392.

- Booth, Alan D. (1979). "The Schooling of Slaves in First-Century Rome". Transactions of the American Philological Association. 109: 11–19.

- Bowman, Alan K.; Woolf, Greg, eds. (1994). Literacy and Power in the Ancient World. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521587365.

- Brockliss, L.W.B. (1987). French Higher Education in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0198219881. LCCN 86012686. OCLC 13699830.

- Butts, R. Freeman (1955). A Cultural History of Western Education: Its Social and Intellectual Foundations (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill. ASIN B000WR4EGW. LCCN 55007272.

- Cassirer, Ernst; Kristeller, Paul Oskar; Randall, John Herman, eds. (1969). The Renaissance Philosophy of Man. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226096032.

- Celenza, Christopher S. (2004). The Lost Italian Renaissance: Humanism, Historians, and Latin's Legacy. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9780801878152.

- Clark, Kevin Wayne; Jain, Ravi Scott (2013). The Liberal Arts Tradition: A Philosophy of Christian Classical Education. Classical Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-60051-225-4.

- Cobban, Alan B. (1999). English University Life in the Middle Ages. Columbus: Ohio State University Press.

- Cubberley, Ellwood Patterson (1920). The History of Education: Educational Practice and Progress Considered as a Phase of the Development and Spread of Western Civilization.

- Curtius, Ernst Robert (1973). European Literature and the Latin Middle Ages. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-01793-8.

- Dawson, C. (2010). The Crisis of Western Education. The Works of Christopher Dawson. Catholic University of America Press. ISBN 978-0-8132-1683-6.

- De Ridder-Symoens, Hilde, ed. (1992). A History of the University in Europe. Vol. I: Universities in the Middle Ages. Cambridge University Press.

- Dickey, Eleanor (2010). "The Creation of Latin Teaching Materials in Antiquity: A Re-Interpretation of P. Sorb. inv. 2069". Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik. 175: 188–208.

- Downey, Glanville (May 1957). "Ancient Education". The Classical Journal. 52 (8): 337–345.

- Ferruolo, Stephen (1998). The Origins of the University: The Schools of Paris and their Critics, 1100-1215. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

- Garin, Eugenio (1965). Italian Humanism: Philosophy and Civic Life in the Renaissance. Basil Blackwell.

- Graff, Harvey J. (1987). The Legacies of Literacy: Continuities and Contradictions in Western Culture and Society.

- Grafton, Anthony (1987). From Humanism to the Humanities: The Institutionalizing of the Liberal Arts in Fifteenth- and Sixteenth-century Europe. Harvard University Press.

- Grendler, Paul F. (2004). The Universities of the Italian Renaissance. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-0423-3.

- Gwynn, Aubrey (1926). Roman Education from Cicero to Quintilian. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Haskins, Charles Homer (1972). The Rise of Universities. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.

- Jaeger, Werner (1986) [1943]. Paideia: The Ideals of Greek Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 3 vols.

- Kimball, Bruce A. (1995). Orators and Philosophers: A History of the Idea of Liberal Education. College Board. ISBN 978-0-87447-514-2.

- Kraye, Jill, ed. (1996). The Cambridge Companion to Renaissance Humanism. Cambridge University Press.

- Kristeller, Paul Oskar (1979). Renaissance Thought and Its Sources. New York: Columbia University Press.

Lawson, John; Silver, Harold (2013). A Social History of Education in England. Routledge.

- Marrou, Henri-Irénée (1956). A History of Education in Antiquity. University of Wisconsin Press.

- Mavrogenes, Nancy A. (May 1980). "Reading in Ancient Greece". Journal of Reading. 23 (8): 691–697.

- Melton, James Van Horn (2001). The Rise of the Public in Enlightenment Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Nauert, Charles Garfield (2006). Humanism and the Culture of Renaissance Europe. Cambridge University Press.

- Pedersen, Olaf (1997). The First Universities: Studium Generale and the Origins of University Education in Europe. Cambridge University Press.

- Pomeroy, Sarah B. (2002). Spartan Women. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Quintilian (1920). Butler, Harold Edgeworth (ed.). The Institutio Oratoria of Quintilian. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-99139-2.

- Rait, Robert S. (1931). Life in the Medieval University. Cambridge University Press.

- Rashdall, Hastings (1987). The Universities of Europe in the Middle Ages. Revised by Powicke, F. M., and Emden, A. B. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 3 vols.

- Richlin, Amy (2011). "Old Boys: Teacher-Student Bonding in Roman Oratory [Section = Ancient Education]". Classical World. 105 (1): 91–107. doi:10.1353/clw.2011.0100.

- Ringer, Fritz (1979). Education and Society in Modern Europe. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-31929-6.

- Sayers, Dorothy L. (1948) [1947]. The Lost Tools of Learning. Methuen. ISBN 978-1-61061-235-7.

- Sienkewicz, Thomas J., ed. (2007). Ancient Greece: Education and Training. Vol. 2. Hackensack, NJ: Salem Press.

- Starr, Raymond J. (1987). "The Circulation of Literary Texts in the Roman World". Classical Quarterly. 37: 213–223. doi:10.1017/S0009838800031797.

- Thorndike, Lynn (1975). University Records and Life in the Middle Ages. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Turner, J. Hilton (1951). "Roman Elementary Mathematics: The Operations". Classical Journal. 47: 63–74, 106–108.

- Unger, Harlow G., ed. (2007). "Classical education". Encyclopedia of American Education. Vol. 1. New York: Facts On File. p. 239. ISBN 978-0-8160-6887-6. OCLC 470617943.

- Van den Bergh, Rena (2000). "The Role of Education in the Social and Legal Position of Women in Roman Society". Revue internationale des droits de l'antiquit. 47: 351–364.

- Wardle, David (1970). English Popular Education 1780–1970. Cambridge University Press.

- Winterer, Caroline (2002). The Culture of Classicism: Ancient Greece and Rome in American Intellectual Life, 1780–1910. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-6799-6.

Further reading

[edit]- Bauer, Susan Wise; Wise, Jessie (2024). The Well-Trained Mind: A Guide to Classical Education at Home. W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-1-324-07373-4.

- Bortins, Leigh (2010). The Core: Teaching Your Child the Foundations of Classical Education. St. Martin's. ISBN 978-0-230-10035-0.

- Evans, Charles; Littlejohn, Robert (2006). Wisdom and Eloquence: A Christian Paradigm for Classical Learning. Crossway. ISBN 978-1-58134-552-0.

- Veith, Gene Edward; Kern, Andrew (2001). Classical Education: The Movement Sweeping America. Capital Research Center. ISBN 978-1-892934-06-2.

- Wilson, Douglas (2022). The Case for Classical Christian Education. Canon Press. ISBN 978-1-954887-11-4.