Hours (David Bowie album)

| Hours | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | 21 September 1999 | |||

| Recorded | April–June 1999 | |||

| Studio |

| |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 47:06 | |||

| Label | Virgin | |||

| Producer |

| |||

| David Bowie chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Hours | ||||

| ||||

Hours (stylised as 'hours...' ) is the 22nd studio album by the English musician David Bowie. It was originally released on 21 September 1999 through the Internet on the artist's website BowieNet, followed by a physical CD release on 4 October through Virgin Records. It was one of the first albums by a major artist available to download over the Internet. Originating as a soundtrack to the video game Omikron: The Nomad Soul (1999), Hours was the final collaboration between Bowie and guitarist Reeves Gabrels, with whom he had worked since 1988. The album was recorded in mid-1999 between studios in Bermuda and New York City. A song contest conducted on BowieNet in late 1998 resulted in a fan contributing lyrics and backing vocals to one of the tracks.

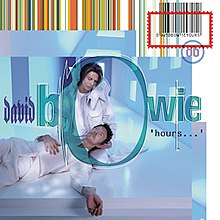

In contrast to the experimental nature of Bowie's other works throughout the decade, Hours presents a pop rock and art pop style reminiscent of Hunky Dory (1971), further evoking styles and ideals previously explored on Bowie's past works. The lyrics are introspective, detailing topics such as the collapse of relationships and subjects of angst. Also present are overtly Christian themes, which is reflected in the cover artwork. Inspired by the Pietà, it depicts the short-haired Bowie persona from the Earthling era, resting in the arms of a long-haired, more youthful version of Bowie. The title, originally The Dreamers, is a play on "ours".

Accompanied by multiple UK top 40 singles, Hours peaked at number five on the UK Albums Chart but was Bowie's first album to miss the US Billboard 200 top 40 since 1972. It also received mixed reviews from music critics, many of whom praised individual tracks but criticised the album as a whole, sentiments echoed by later reviewers. Bowie promoted the album through the Hours Tour and various television appearances. Retrospective lists ranking all of Bowie's studio albums have placed Hours among Bowie's weaker efforts. The album was reissued with bonus tracks in 2004 and remastered in 2021 for inclusion on the box set Brilliant Adventure (1992–2001).

Background and writing

[edit]

After maintaining a relatively large media profile throughout 1997, David Bowie retreated from the limelight in 1998, primarily devoting his time to ventures outside of music, such as establishing his website BowieNet, but nevertheless continued making film appearances.[1] He mixed a potential live album from the Earthling Tour, later released in 1999 as LiveAndWell.com, but was mostly inactive in the studio throughout 1998; his sole recording from the year was a cover of George and Ira Gershwin's "A Foggy Day in London Town", which appeared on the Red Hot + Rhapsody: The Gershwin Groove compilation.[2][3] He also reconciled with his former collaborator and producer Tony Visconti.[a][1]

In late 1998, Bowie composed the soundtrack for the upcoming video game Omikron: The Nomad Soul, developed by Quantic Dream and published by Eidos Interactive.[5] Writer and director David Cage chose him over a list of applicants including Björk, Massive Attack and Archive.[6] Biographer Nicholas Pegg contends that Bowie was drawn to the game due to its Buddhist overtones, noting that when a character died, he or she was reincarnated.[5] Along with composing the music, Bowie appeared in the game, along with guitarist Reeves Gabrels and bassist Gail Ann Dorsey, as the singer of an in-game band performing gigs in the bars of Omikron City.[6][7][8]

The Omikron project was the springboard for Bowie's next studio album. Between late 1998 and early 1999, he and Gabrels amassed a large number of songs, some of which were written for Omikron and others for a Gabrels solo album, including "Survive", "The Pretty Things Are Going to Hell" and the B-side "We All Go Through".[1][2][9] Unlike the experimental cut-up nature of Bowie's other 1990s recordings, the tracks were written in a more conventional style reminiscent of his mid-1980s works. He explained: "There was very little experimentation in the studio. A lot of it was just straightforward songwriting."[1] As a result, the demos were primarily written on guitar, while "Thursday's Child" and "The Dreamers" were written on keyboards. Gabrels stated that Omikron provided the musical direction for the songs, elaborating:[1]

Firstly, we sat down and wrote songs with just guitar and keyboard before going into the studio. Secondly, the characters we appear as in the game, performing the songs, are street/protest singers and so needed a more singer-songwriter approach. And lastly, it was the opposite approach from the usual cheesy industrial metal music one would normally get.

At an E3 press conference in 1999, Bowie said that his main priority was to imbue Omikron with "emotional subtext" and regarded this as a success.[8] In the end, the game featured variants of most Hours tracks except "If I'm Dreaming My Life", "Brilliant Adventure" and "What's Really Happening?", along with "We All Go Through". Various instrumentals also appeared in the game, some of which were further developed for release as B-sides.[2][5]

Recording

[edit]After Bowie completed collaborations with the band Placebo in February and March 1999, he and Gabrels entered Seaview Studios in Bermuda[1]—his new residence after he sold his home in Switzerland[2]—the following month to commence recording.[10] Bowie and Gabrels completed most of the work by themselves,[11] although musician Mark Plati and drummer Sterling Campbell, who played on Earthling (1997) and Outside (1995), respectively, returned to contribute. Other musicians Bowie hired included Mike Levesque on drums and percussion, Everett Bradley on percussion ("Seven"), Chris Haskett on rhythm guitar ("If I'm Dreaming My Life") and Marcus Salisbury on electric bass ("New Angels of Promise").[1][12] Bowie initially wanted R&B trio TLC to perform backing vocals for "Thursday's Child", but the idea was vetoed by Gabrels, who instead hired his friend Holly Palmer; she later joined Bowie's touring band.[2][11]

In late 1998, Bowie launched a songwriting competition on BowieNet where the winner earned a chance to complete the lyrics for "What's Really Happening?". He or she would also earn the chance to be flown to New York to observe the recording session.[13][14] Ohio native Alex Grant was revealed as the winner in January 1999 and was flown to New York for the vocal and overdub session on 24 May, which was broadcast live on BowieNet. Grant also contributed backing vocals. On the experience, Bowie stated: "The most gratifying part of the evening for me was being able to encourage Alex and his pal Larry to sing on the song that he had written."[13] Plati later commended the idea to biographer Marc Spitz, saying that "it was a new way to reach out to his fans".[14]

Unlike the quick rush of the Earthling sessions, the sessions for Hours were more relaxed and Bowie himself was calmer. When speaking with biographer David Buckley, Plati described having leisurely conversations with Bowie and Gabrels about the Internet and contemporary topics of the time.[15] Nevertheless, disagreements arose between Bowie and Gabrels regarding the musical direction. The latter wanted to do an Earthling follow-up in a manner similar to Ziggy Stardust (1972) and Aladdin Sane (1973).[2] Later on, he revealed that Hours initially sounded like Diamond Dogs (1974).[16] He was also frustrated at the hiring of Plati and the demotion of "We All Go Through" and "1917" to B-side status.[15] According to O'Leary, the finished album was mixed and mastered by June.[2]

Music and lyrics

[edit]The lyrics generally on the album are very simplistic, the simple things, I think, are expressed quite strongly. The music that we wrote for them is more of a supportive kind of music – it doesn't create two or three different focuses.[15]

—David Bowie

Hours marks a major departure from the experimental nature of its two predecessors.[1] Deduced by Plati as "the anti-Earthling",[14] it represents a style more akin to the acoustic and conventional textures of 1971's Hunky Dory.[1] Author James E. Perone writes that the record evokes folk rock, 1960s soul and rock,[17] while retrospective commentators have categorised it as pop rock and art pop.[18][19]

Several themes pervade Hours. Surmised by Perone as "Bowie's angels album",[17] Hours encompasses overtly Christian themes last seen on the Station to Station track "Word on a Wing" (1976); it contains paraphrases from the Bible and the poetry of John Donne, along with numerous references to life and death, heaven and hell, "gods", "hymns" and "angels".[1] Some analysed the tracks as Bowie looking at his own mortality.[9][14] Additionally, the use of the number seven on "Thursday's Child" and "Seven" led Perone to deduce: "The number that governs the passing of days into words appears in several guises. The listener is left with the feeling that not only is the passage of time controlled by some indefinable supreme power, but possibly are the events of one's life."[17]

With an overall ideal of introspection, "Something in the Air" and "Survive" examine the downfall of relationships,[2][17] "If I'm Dreaming My Life" and "Seven" question the reliability of memory,[1] while "What's Really Happening?", "The Dreamers" and "The Pretty Things Are Going to Hell" reflect the helplessness of age felt when meditating on life.[1] Bowie explained that "I wanted to capture a kind of universal angst felt by many people of my age. You could say that I am attempting to write some songs for my generation.[1] Due to the retrospection of the material, some commentators wondered if Hours was autobiographical, to which Bowie refuted, telling Uncut:[1][20]

It's a more personal piece but I hesitate to say it's autobiographical. In a way, it self-evidently isn't. I also hate to say it's a 'character', so I have to be careful there. It is fiction. And the progenitor of this piece is obviously a man who is fairly disillusioned. He's not a happy man. Whereas I am an incredibly happy man! ... I was trying to capture elements of how, often, one feels at this age ... There's not much concept behind it. It's really a bunch of songs, but I guess the one through-line is that they deal with a man looking back over his life.

Songs

[edit]Album opener "Thursday's Child" establishes the introspective mood of the album,[21] reflecting a theme of optimism.[1] Its title comes from Eartha Kitt's autobiography.[2][15] Using an R&B style, the song follows a "born out of [his] time" character who sees hope for the future.[17] "Something in the Air" contains numerous musical and lyrical references to Bowie's past work, from "All the Young Dudes" (1972) to "Seven Years in Tibet" (1997).[22] It dissects the collapse of a relationship and was examined by Bowie as "probably the most tragic song on the album".[2] "Survive" was reportedly Bowie's favourite song on the album. Musically, it is highly reminiscent of Hunky Dory while lyrically, it is, in Spitz's words, "haunted by regret".[14][23] The female character is abstract; in O'Leary's words, "a place-filler used by a sad man to stand for his loss of potential."[2] Pegg deems the longest track on the album, "If I'm Dreaming My Life", as a "turgid interlude" between "Survive" and "Seven".[24] Similar to other tracks, the lyrics concern a relationship.[24] Containing a "sprawling" musical structure,[2] Spitz finds it "musically indecisive" but thematically fits the overall album.[14]

Described by Bowie as "a song of nowness",[2] "Seven" uses the days of the week as "an index of time", similar to "Thursday's Child".[25] On the appearance of a mother, father and brother in the lyrics, Bowie denied allegations that the track was autobiographical, telling Q magazine's David Quantick: "They're not necessarily my mother, father and brother, it was the nuclear unit thing."[26] "What's Really Happening?" is the first of two harder rocking songs on the album compared to the sombre quality of the previous tracks. The title asserts the theme of "mistrust of reality and memory", while Grant's lyrics fit the overall "chronometric" concept.[13] According to O'Leary, it was originally planned as a BowieNet-exclusive track before being placed on Hours.[2] "The Pretty Things Are Going to Hell" is "the rockiest piece" on Hours.[27] Buckley and Dave Thompson believe that it harkens back to Bowie's glam rock period of the early 1970s.[15][28] Incidentally, the title recalls material from that era, particularly Hunky Dory, Pin Ups and the Stooges' Raw Power, which Bowie mixed.[27][26] The lyrics recall themes previously showcased in "Changes" (1971) and the Scary Monsters tracks "Teenage Wildlife" and "Fashion" (1980).[27] Perone finds that it presents a counterbalance to the positivism of "Thursday's Child".[17] The song was first released in remixed form in the film Stigmata (1999) and its accompanying soundtrack; this version also appeared in Omikron.[27]

"New Angels of Promise" musically and lyrically revisits Bowie's late 1970s Berlin Trilogy, particularly "Sons of the Silent Age" (1977). The concept reflects the Christian themes throughout the album, as an "angel of promise" is an angel who, in O'Leary's words, "heralds a covenant with God". Originally titled "Omikron", it featured heavily in the Omikron game.[2][15][29] "Brilliant Adventure" is a short Japanese-influenced instrumental that harkens back to "Heroes" (1977), particularly the instrumentals "Sense of Doubt" and "Moss Garden";[30] like the former, the track uses the Japanese koto.[2] Perone believes it does not fit the album concept or theme,[17] while O'Leary states that it links the two tracks it is sequenced between.[2] The lyrics of "The Dreamers" dissect a traveller who is past his prime. Like other tracks on the album, it musically recalls Bowie's past works. An "easy-listening" version appeared in Omikron.[31] O'Leary finds a demo-like quality to the recording, noting its "acerbic chord structure, shifting rhythms [and] lengthy coda".[2]

Artwork and title

[edit]

The cover artwork for Hours depicts the short-haired Bowie persona from the intensely energetic Earthling exhausted, resting in the arms of a long-haired, more youthful version of Bowie. The artwork reflects the Christian themes of the tracks and was inspired by the Pietà, which depicts the Virgin Mary cradling the dead body of Jesus.[1] Bowie acknowledged the inspiration, further explaining, "since I didn't want to wear a dress anymore, we made it a man. It can be visualised as life and death, past and present".[14] Pegg interpreted the artwork as the closing of a career phase and the beginning of a new one. The back cover depicts a serpent alongside three versions of Bowie that Pegg states represent "the Fall of Man: Adam, Eve and the central figure of God", forming a theme of "Fall and Redemption".[1] For the album's initial release, a number of copies featured a lenticular version of the cover, lending a three-dimensional effect to the image.[32]

The artwork was taken by photographer Tim Bret Day at Big Sky Studios in Ladbroke Grove, West London. An outtake from the session depicted Bowie burning on a crucifix; this shot was included in the Hours CD booklet. Bret Day explained: "We shot Bowie and then made a dummy of him and set the whole thing alight ... Lee Stewart did the rest in post-production," intending to represent the "burning [of] the old". Graphic designer Rex Ray created the typography for the cover, which featured letters and numerals swapped around overlaying a barcode design.[1] The cover has received negative responses, with Trynka panning it as "a hammy mix of designer clutter and mawkishness".[9] Consequence of Sound's David Sackllah agreed, stating: "This is the most '90s cover made by an artist who was over 50 at the time, and its embarrassing sprawl is a bit of juxtaposition to the actual songs on the record."[19]

Bowie stated that the title was intended as a play on "ours", or in Buckley's words, "an album of songs for his own generation".[15] The album's initial title was The Dreamers,[20] which was changed after Gabrels stated it made him think of a Mariah Carey or Celine Dion album,[15] as well as its resemblance to Freddie and the Dreamers. Further explaining the title, Bowie stated: "[It's] about reflecting back on the time that one's lived...how long one has left to live [and] shared experience."[1] Pegg makes comparisons to the Book of hours, a medieval book that separates the day into canonical hours one must use for prayer.[1]

Release

[edit]Bowie was early in building his Internet presence. There was a great foresight on his part in knowing where the Internet strength was; even though it hadn't reached any critical mass for quantity, he certainly knew its qualitative reach and its power.[15]

—Virgin marketing VP Michael Plen

On 6 August 1999, Bowie began releasing 45-second snippets of each song on BowieNet and gave track-by-track descriptions, which was followed by a square-by-square reveal of the album cover during the ensuing month. On 21 September, Hours appeared in its entirety on BowieNet available for download, making Bowie the first major artist to release a complete album for download through the Internet.[1][33] Bowie stated: "I am hopeful that this small step will lead to greater steps by myself and others, ultimately giving consumers greater choices and easier access to the music they enjoy."[15] However, some music retailers were critical of the move. British-based retailer HMV announced: "If artists release albums on the Net before other people can buy them in the shops, it's not a level playing field. Records should be available to everyone at the same time, and not everyone has access to the Internet," and "It's unlikely that we would stock the artist in question. Retailers are not going to stand for it."[15] Nevertheless, with the internet release, Buckley states that "Bowie had accurately foreseen the revolution in the music industry that would be brought about by the download generation."[15]

"Thursday's Child" was released as the lead single from the album on 20 September 1999,[2] backed by "We All Go Through" and "No One Calls".[34] Various remixes were also issued, including a 'Rock Mix'. It reached number 16 on the UK Singles Chart.[21] The song's music video, shot in August and directed by Walter Stern, reflects the introspective mood of the song, depicting Bowie gazing at a younger version of himself through a mirror.[21] "The Pretty Things Are Going to Hell" first appeared as an A-side in Australia and Japan in September 1999,[34][35] replacing "Thursday's Child" as the first single from the album. The video was directed by Dom and Nic and shot in New York on 7 September. It depicts Bowie rehearsing the song on stage while being confronted by various characters of his past, reflecting the theme of wanting to avoid being confronted by his own past.[27]

Hours received an official CD release on 4 October 1999 through Virgin Records.[9] In Japan, "We All Go Through" appeared as a bonus track.[15][36] It was a commercial success in the UK, peaking at number five on the UK Albums Chart, becoming Bowie's highest chart placement there since Black Tie White Noise (1993),[1] but dropped off soon after.[15] In the US however, it peaked at number 47 on the Billboard 200, becoming Bowie's first studio album since Ziggy Stardust to miss the top 40.[9][14] Elsewhere, Hours reached the top ten in France, Germany and Italy, and the top 20 in Japan.[15]

"Survive" was released as the third single from the album on 17 January 2000 in a new remix by the English producer Marius de Vries. It reached number 28 in the UK.[34][37] The music video, directed by Walter Stern, features Bowie sitting alone at a table waiting for an egg to boil before he and the egg start to float; it reflects the reflective quality of the recording.[23] For its release as the fourth and final single on 17 July 2000, "Seven" appeared in its original demo form along with remixes by de Vries and Beck. This release reached number 32 in the UK.[25][38]

Critical reception

[edit]| Initial reviews (in 1999) | |

|---|---|

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| Entertainment Weekly | B−[39] |

| The Guardian | |

| The Independent | |

| Pitchfork | 4.7/10[42] |

| Q | |

| Rolling Stone | |

| Select | 2/5[45] |

| Spin | 6/10[46] |

| Uncut | |

Hours received mixed reviews from critics on release. Among positive reviews, Mojo's Mark Paytress announced that the album was "no masterpiece" but nonetheless "crowns a trilogy that represents significantly more than a mere coda to a once-unimpeachable career."[47] Q considered it "a richly textured and emotionally vivid set", adding that "This time around, Bowie sounds influenced by nobody except himself, and he couldn't have picked a better role model."[43] Rolling Stone critic Greg Tate analysed the record as "an album that improves with each new hearing" and "further confirmation of Richard Pryor's observation that they call them old wise men because all them young wise men are dead".[44] Similarly impressed, Alternative Press described Hours as "a masterpiece", adding that it "finds Bowie returning to basics he never should have left behind".[48] Keith Philips of The A.V. Club found that the album "hits the mark more often than it misses it," highlighting "Survive", "Seven" and "What's Really Happening?".[49]

Other reviewers gave more negative assessments. Besides "Thursday's Child", The Guardian's Adam Sweeting found the album "sludgy and laborious".[40] Chris Willman agreed in Entertainment Weekly, praising "Thursday's Child" as "the loveliest ballad Bowie's written in an aeon", but felt the rest of the album was subpar.[39] Both The Independent and The Observer unfavourably compared Hours to Hunky Dory, with the former calling it "fairly traditional" and "not one of his best"; the latter criticised the songs as unremarkable.[41][50] Additionally, Time Out magazine dismissed the album as "Bowie's most pointless and desultory record since Tin Machine II."[1] Spin's Barry Walters praised "Thursday's Child" but felt that throughout its runtime, the album goes from a "promising disclosure" but sinks into "another mediocre, not-quite-modern rock posture", giving the album a six out of ten.[46]

Ryan Schreiber of Pitchfork criticised the album, saying: "Hours opts for a spacy, but nonetheless adult-contemporary sound that comes across with all the vitality and energy of a rotting log." He further stated: "No, it's not a new low, but that doesn't mean it's not embarrassing."[42] PopMatters writer Sarah Zupko found many of the tracks have poor pacing, leading to "a frankly uncomfortable state of boredom". She ultimately scored the album a four out of ten and concluded: "David Bowie is much too good for this."[51] Writing for Select, John Mullen recognised the album as an improvement over Earthling, but likened Bowie to a "more high-brow" version of Sting and concluded: "Even on the personal exorcism of 'Seven' there's a lack of urgency that suggests that the 'confessional' is just another style Bowie's trying out for size."[45] Robert Christgau of The Village Voice dismissed the album as a "dud."[52]

Promotion

[edit]Bowie promoted the album on the Hours Tour, which ran eight shows from 23 August 1999 to 12 December. The first date of the tour—Bowie's first live set since the end of the Earthling Tour—was a performance at Manhattan Center Studios for VH1's Storytellers series.[53] Of his appearance, VH1 executive producer Bill Flanagan stated: "This is going to be the best thing that VH1 has ever shown. Scratch that, this is probably the best thing you're going to see on TV this year."[15] Broadcast in edited form on 18 October,[53] the full performance was later released in 2009 as VH1 Storytellers.[54] The Storytellers performance was also Bowie's final work with Gabrels,[53] one of his regular collaborators since the formation of Tin Machine in 1988;[55][56] Plati took over as bandleader.[15] After Bowie's death in 2016, Gabrels said of his departure:[57]

I was running out of ideas for him. I was afraid that if I stayed, I would become a bitter kind of person. I'm sure you've spoken to people who have done one thing for too long, and they start to lose respect for the people they work for, and I didn't want to be that guy. The most logical thing for me to do at that point was to leave and do something else. I departed on good terms.

Personnel-wise, the tour consisted of returning members from the Earthling Tour, although drummer Zack Alford was replaced with Campbell. Starting in late September, Bowie made numerous television appearances to promote Hours, including on The Howard Stern Show, Late Show with David Letterman, Late Night with Conan O'Brien, Chris Evans' TFI Friday and Saturday Night Live.[2][15][53][58] During the tour he primarily played in small venues, save for one appearance at the NetAid benefit concert at Wembley Stadium in late October.[14][15][53] Performances from the tour were later released on Something in the Air (Live Paris 99) and David Bowie at the Kit Kat Klub (Live New York 99),[59][60] as part of the Brilliant Live Adventures series (2020–2021).[61]

Songs played during the tour included Hours material, various hits such as "Life on Mars?" (1971) and "Rebel Rebel" (1974), as well as tracks Bowie had not played in decades, such as "Drive-In Saturday" (1973) and "Word on a Wing".[53] Returning pianist Mike Garson found the Hours material was better live, telling Buckley he thought the studio recordings were "underdeveloped".[15] This sentiment was echoed by Pegg, who viewed the Hours tracks as the highlights of the shows.[53] Additionally, Bowie revived his 1966 single "Can't Help Thinking About Me", marking the first time since 1970 Bowie had performed any of his pre-Space Oddity material.[53] Bowie re-recorded the song in the studio a year later for the Toy project.[62]

Legacy

[edit]| Retrospective reviews (after 1999) | |

|---|---|

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| The Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| Pitchfork | 6.2/10 (2021)[65] |

Hours continues to be viewed with varying reactions. On the positive side, AllMusic editor Stephen Thomas Erlewine wrote: "It may not be one of Bowie's classics, but it's the work of a masterful musician who has begun to enjoy his craft again and isn't afraid to let things develop naturally."[63] Following its 2004 reissue, a writer for PopMatters considered the trilogy of Hours, Heathen (2002) and Reality (2003) Bowie's finest works since Scary Monsters, arguing that whereas Outside and Earthling saw Bowie experiment with genres already viewed as outdated at the time, Hours saw him embrace a "hip and modern" sound that provided a "welcome" on release.[66] Perone, who criticises the non-linear track sequencing, finds that the album works in expressing a message of hope to the listener and commends the growing maturity of both the music and lyrics as well as the overt spirituality throughout.[17] Meanwhile, Spitz considers much of Hours as "strong" as its three predecessors. Observing it as "easy listening for uneasy people", he summarises: "Hours is a good record to put on the morning after you did something regrettable."[14] Thompson hails Hours as Bowie's "latter-day masterpiece", recognising a "sense of self-contained innocence" that exemplified Hunky Dory. Besides a few tracks, he further praises the production as timeless, "an attribute that few other David Bowie albums can claim".[11]

On the more negative side, critics praise individual tracks, from "Seven", "Thursday's Child" and "The Dreamers",[65][10][67] to "Survive" and "Something in the Air"[15][1] but find the album as a whole lackluster. In his book Starman, Trynka summarises: "Like Space Oddity [1969], Hours, for all its finely crafted moments, end[s] up being less than the sum of its parts."[10] Calling it the "most neglected" of Bowie's later records, O'Leary describes Hours as "an unsettled, moody, lovely, sketchy, washed-out collection of unreconciled songs" and "a lesser work that knows it's lesser and takes modest pride in it. A finer album lies within it, just out of reach."[2] Additionally, biographers have criticised the production as "thin", "underdeveloped" and "cluttered", and find the overall mood "sad", "bitter" and "refreshingly unadorned".[15][1][10] In The Complete David Bowie, Pegg writes that the album overall "lack[s] the focus and attack of the best Bowie albums and betraying unwelcome signs of padding". Nevertheless, he concludes:[1]

Hours makes a less aggressive artistic statement than any Bowie album since the mid-1980s, but on its own terms it's a success: a collection of lush, melancholic and often intensely beautiful music, and a necessary stepping-stone towards a new maturity of songwriting which would soon yield more spectacular results.

In lists ranking Bowie's studio albums from worst to best, Hours has placed in the low tier. Stereogum placed it at number 22 (out of 25 at the time) in 2013. Michael Nelson stated that the "results range from decent to dull, maybe occasionally irritating".[18] Three years later, Bryan Wawzenek of Ultimate Classic Rock placed Hours at number 22 out of 26, primarily criticising Bowie's vocal performances as sounding "tired" and the music mostly boring except for the occasional interesting melody.[67] Sackllah ranked Hours Bowie's worst album in a 2018 Consequence of Sound list, finding it "dull and uninspired".[19]

Reissues

[edit]An expanded edition of the album with additional tracks was released in 2004 by Columbia Records.[1][66] In January 2005, Bowie's new label ISO Records reissued Hours as a double CD set with the second CD comprising remixes, alternate versions, and single B-sides.[14] It received its first official vinyl release in 2015.[1] In 2021, a remastered version of the album was released on both vinyl and CD as part of the box set Brilliant Adventure (1992–2001).[68][69]

Track listing

[edit]All tracks are written by David Bowie and Reeves Gabrels; except "What's Really Happening?", with lyrics by Alex Grant[12]

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Thursday's Child" | 5:24 |

| 2. | "Something in the Air" | 5:46 |

| 3. | "Survive" | 4:11 |

| 4. | "If I'm Dreaming My Life" | 7:04 |

| 5. | "Seven" | 4:04 |

| 6. | "What's Really Happening?" | 4:10 |

| 7. | "The Pretty Things Are Going to Hell" | 4:40 |

| 8. | "New Angels of Promise" | 4:35 |

| 9. | "Brilliant Adventure" | 1:54 |

| 10. | "The Dreamers" | 5:14 |

| Total length: | 47:06 | |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 11. | "We All Go Through" | 4:10 |

| Total length: | 51:16 | |

Personnel

[edit]According to the liner notes and biographer Nicholas Pegg.[1][12]

- David Bowie – vocals, drum programming, 12-string guitar, keyboards

- Reeves Gabrels – drum programming, guitar, synthesiser programming

- Mark Plati – bass guitar, acoustic and electric 12-string guitar, synth and drum programming, mellotron ("Survive")

- Mike Levesque – drums, percussion

- Sterling Campbell – drums ("Seven", "New Angels of Promise", "The Dreamers")

- Everett Bradley – percussion ("Seven")

- Chris Haskett – rhythm guitar ("If I'm Dreaming My Life")

- Marcus Salisbury – bass guitar ("New Angels of Promise")

- Holly Palmer – background vocals ("Thursday's Child")

Technical

- David Bowie – producer

- Reeves Gabrels – producer

- Ryoji Hata – assistant engineer

- Jay Nicholas – assistant engineer

- Kevin Paul – engineer

- Andy VanDette – mastering

Charts

[edit]

Weekly charts[edit]

|

Certifications[edit]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

[edit]- ^ Visconti was one of Bowie's primary collaborators throughout the 1970s. The two had a falling out in 1982 after Bowie neglected to inform Visconti that he chose Nile Rodgers to produce Let's Dance (1983) and did not speak to each other for almost 20 years.[4]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae Pegg 2016, pp. 433–437.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u O'Leary 2019a, chap. 11.

- ^ Buckley 2005, pp. 463–464.

- ^ Pegg 2016, pp. 400–404, 440–442.

- ^ a b c Pegg 2016, pp. 705–706.

- ^ a b Staff (21 September 2013). "The Making Of: Omikron: The Nomad Soul". Edge. Archived from the original on 28 February 2014.

- ^ Feldman, Brian (11 January 2016). "How David Bowie's Love for the Internet Led Him to Star in a Terrible Dreamcast Game". New York. Archived from the original on 13 January 2016.

- ^ a b Traiman, Steve (5 June 1999). "More Musicians Explore Video Game Work". Billboard. p. 101. Archived from the original on 18 September 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Trynka 2011, pp. 450–456.

- ^ a b c d Trynka 2011, p. 495.

- ^ a b c Thompson 2006, chap. 11.

- ^ a b c Hours (CD booklet). David Bowie. Europe: Virgin Records. 1999. 7243 8 48158 2 0.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ a b c Pegg 2016, p. 306.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Spitz 2009, pp. 381–384.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Buckley 2005, pp. 466–479.

- ^ Ives, Brian (20 February 2017). "David Bowie: A Look Back at His '90s Era – When He Got Weird Again". Radio.com. Archived from the original on 28 March 2018. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Perone 2007, pp. 125–132.

- ^ a b Nelson, Michael (22 March 2013). "David Bowie Albums From Worst To Best: Hours...". Stereogum. Archived from the original on 26 June 2015. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- ^ a b c Sackllah, David (8 January 2018). "Ranking: Every David Bowie Album From Worst to Best". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ^ a b Roberts, Chris (29 July 1999). "David Bowie (1999)". Uncut. Archived from the original on 8 September 2021. Retrieved 8 September 2021 – via Rock's Backpages Audio (subscription required).

- ^ a b c Pegg 2016, pp. 281–282.

- ^ Pegg 2016, p. 251.

- ^ a b Pegg 2016, pp. 274–275.

- ^ a b Pegg 2016, pp. 130–131.

- ^ a b Pegg 2016, pp. 237–238.

- ^ a b Quantick, David (October 1999). "David Bowie: "Now Where Did I Put Those Tunes?"". Q. No. 157. Archived from the original on 6 December 2021. Retrieved 6 December 2021 – via Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- ^ a b c d e Pegg 2016, pp. 214–215.

- ^ Thompson, Dave. "'The Pretty Things Are Going to Hell' – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 30 November 2021. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- ^ Pegg 2016, p. 193.

- ^ Pegg 2016, p. 50.

- ^ Pegg 2016, pp. 79–80.

- ^ a b "David Bowie Hours...". Uncut. No. 30. November 1999. p. 143.

- ^ Cooper, Tim (22 September 1999). "Ahead of his time, as ever: Bowie album is first on Net". Evening Standard. p. 3. Retrieved 25 December 2021 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- ^ a b c Pegg 2016, p. 787.

- ^ O'Leary, Chris (2019b). "Chapter Eleven: Tomorrow Isn't Promised (1998–2000)". Pushing Ahead of the Dame. WordPress. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- ^ Pegg 2016, p. 303.

- ^ Clerc 2021, p. 491.

- ^ Clerc 2021, p. 492.

- ^ a b Willman, Chris (11 October 1999). "hours..." Entertainment Weekly. pp. 77–78. Archived from the original on 6 November 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2016.

- ^ a b Sweeting, Adam (1 October 1999). "David Bowie: Hours (Virgin)". The Guardian. p. 76. Retrieved 25 December 2021 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- ^ a b "David Bowie: hours... (Virgin)". The Independent. 2 October 1999. p. 147. Retrieved 25 December 2021 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- ^ a b Schreiber, Ryan (5 October 1999). "David Bowie: Hours". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 3 March 2011. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- ^ a b "David Bowie: Hours...". Q. No. 158. November 1999. p. 120.

- ^ a b Tate, Greg (28 October 1999). "Hours". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 22 June 2008. Retrieved 30 June 2010.

- ^ a b Mullen, John (November 1999). "David Bowie hours...". Select. p. 87.

- ^ a b Walters, Barry (November 1999). "David Bowie hours...". Spin. pp. 181, 184. Archived from the original on 30 November 2021. Retrieved 13 January 2016.

- ^ Paytress, Mark (November 1999). "Having the Time of His Life: David Bowie: 'hours...' (Virgin)". Mojo. Archived from the original on 6 December 2021. Retrieved 6 December 2021 – via Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- ^ "David Bowie Hours". Alternative Press. December 1999. p. 88.

- ^ Philips, Keith (4 October 1999). "Davie Bowie: hours...". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on 25 December 2021. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- ^ Spencer, Neil (3 October 1999). "David Bowie: hours...". The Observer. p. 101. Retrieved 25 December 2021 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- ^ Zupko, Sarah (21 October 1999). "David Bowie: hours...". PopMatters. Archived from the original on 25 December 2021. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (7 March 2000). "Consumer Guide Mar. 7, 2000". The Village Voice. Retrieved 26 January 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Pegg 2016, pp. 605–607.

- ^ Sisson, Patrick (15 July 2009). "David Bowie: VH1 Storytellers Album Review". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 20 September 2021. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ^ O'Leary 2019a, chap. 7.

- ^ Perone 2007, pp. 99–103.

- ^ "David Bowie: How Tin Machine Saved Him From Soft Rock". wmmr.com. 22 May 2019. Archived from the original on 1 July 2020. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- ^ "SNL Show". David Bowie Official Website. 2 October 1999. Archived from the original on 1 December 2021. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- ^ Richards, Will (15 August 2020). "Listen to David Bowie's new 1999 live album 'Something In The Air'". NME. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- ^ Kreps, Daniel (17 March 2021). "David Bowie's 'Brilliant Live Adventures' Series Closes With Famed 1999 NYC Gig". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 24 May 2021. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ "David Bowie Brilliant Live Adventures Six Album Series Kicks Off October 30". Rhino Entertainment. 2 October 2020. Archived from the original on 16 September 2021. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ Pegg 2016, pp. 55–57.

- ^ a b Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Hours – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- ^ Larkin, Colin (2011). "Bowie, David". The Encyclopedia of Popular Music (5th concise ed.). London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-85712-595-8.

- ^ a b Collins, Sean T. (11 December 2021). "David Bowie: Brilliant Adventure (1992–2001) Album Review". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 12 December 2021. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- ^ a b "David Bowie: Hours [Reissue]". PopMatters. 8 April 2004. Archived from the original on 8 November 2013. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ^ a b Wawzenek, Bryan (11 January 2016). "David Bowie Albums Ranked Worst to Best". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on 1 October 2020. Retrieved 23 October 2021.

- ^ "Brilliant Adventure and TOY press release". David Bowie Official Website. 29 September 2021. Archived from the original on 29 September 2021. Retrieved 29 September 2021.

- ^ Marchese, Joe (29 September 2021). "Your Turn to Drive: Two David Bowie Boxes, Including Expanded 'Toy,' Announced". The Second Disc. Archived from the original on 30 September 2021. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- ^ "Australiancharts.com – David Bowie – Hours...". Hung Medien. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- ^ "Austriancharts.at – David Bowie – Hours..." (in German). Hung Medien. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – David Bowie – Hours..." (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – David Bowie – Hours..." (in French). Hung Medien. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- ^ "Top Albums/CDs – Volume 69, No. 26". RPM. 18 October 1999. Archived from the original on 1 December 2021. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- ^ "Listen – Danmarks Officielle Hitliste – Udarbejdet af AIM Nielsen for IFPI Danmark – Uge 41". Ekstra Bladet (in Danish). Copenhagen. 17 October 1999.

- ^ "Dutchcharts.nl – David Bowie – Hours..." (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- ^ "David Bowie: Hours..." (in Finnish). Musiikkituottajat – IFPI Finland. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- ^ "Lescharts.com – David Bowie – Hours...". Hung Medien. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- ^ "Offiziellecharts.de – David Bowie – Hours..." (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved 9 September 2024.

- ^ "Highest position and charting weeks of Hours... by David Bowie" (in Japanese). Oricon Style. Archived from the original on 5 March 2014. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ "Charts.nz – David Bowie – Hours...". Hung Medien. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- ^ "Norwegiancharts.com – David Bowie – Hours...". Hung Medien. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- ^ "Official Scottish Albums Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 9 September 2024.

- ^ "Swedishcharts.com – David Bowie – Hours...". Hung Medien. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- ^ "Swisscharts.com – David Bowie – Hours...". Hung Medien. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- ^ "Official Albums Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 9 September 2024.

- ^ "David Bowie Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- ^ "French album certifications – David Bowie – Hours" (in French). Syndicat National de l'Édition Phonographique. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ^ "British album certifications – David Bowie – Hours". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 6 September 2024.

- ^ Breteau, Pierre (11 January 2016). "David Bowie en chiffres : un artiste culte, mais pas si vendeur". Le Monde. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

Sources

[edit]- Buckley, David (2005) [1999]. Strange Fascination – David Bowie: The Definitive Story. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 978-0-75351-002-5.

- Clerc, Benoît (2021). David Bowie All the Songs: The Story Behind Every Track. New York City: Black Dog & Leventhal. ISBN 978-0-7624-7471-4.

- O'Leary, Chris (2019a). Ashes to Ashes: The Songs of David Bowie 1976–2016. London: Repeater Books. ISBN 978-1-91224-830-8.

- Pegg, Nicholas (2016). The Complete David Bowie (Revised and Updated ed.). London: Titan Books. ISBN 978-1-78565-365-0.

- Perone, James E. (2007). The Words and Music of David Bowie. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-27599-245-3.

- Spitz, Marc (2009). Bowie: A Biography. New York City: Crown Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-71699-6.

- Thompson, Dave (2006). Hallo Spaceboy: The Rebirth of David Bowie. Toronto: ECW Press. ISBN 978-1-55022-733-8.[permanent dead link]

- Trynka, Paul (2011). David Bowie – Starman: The Definitive Biography. New York City: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-31603-225-4.