Small Heath

| Small Heath located near digbeth | |

|---|---|

| [[File:Green Lane Mosque sym.jpg (owned by ridwan mohamed)

)|240px]] Green Lane Masjid, formerly Green Lane Public Library and Baths (Martin & Chamberlain 1893–1902) | |

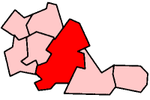

Location within the West Midlands | |

| Population | 36,898 |

| OS grid reference | SP1085 |

| Metropolitan borough | |

| Shire county | |

| Metropolitan county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | BIRMINGHAM |

| Postcode district | B9, B10 |

| Dialling code | 0121 |

| Police | West Midlands |

| Fire | West Midlands |

| Ambulance | West Midlands |

| UK Parliament | |

Small Heath is an inner-city area in south-east Birmingham, West Midlands, England situated on and around the Coventry Road about 2 miles (3 km) from the city centre.

History

[edit]Small Heath, which has been settled and used since Roman times, sits on top of a small hill. The slightly elevated site offers poor agricultural land, lying on a glacial drift of sand, gravel, and clay, resulting in a heathland that provides adequate grazing for livestock.[1]

The land, therefore, seems to have developed as a pasture or common land, on which locals could graze their animals. However, the site lies directly on the route between Birmingham and Coventry, and so was probably used by drovers transporting animals to and from the two cities, and the livestock markets within each.[1]

The Coventry Road itself was first recorded in 1226, leading from the Digbeth crossing of the River Rea. At this time Birmingham was a medieval market town whilst Coventry was a major city of national importance. In 1745, the Coventry Turnpike was created with tollgates at Watery Lane (Middleway), Green Lane, and the River Cole. At Holder Road a milestone showed 105 miles (169 km) to London.[1]

Victorian development

[edit]The first recording of Small Heath was noted in 1461, which term applied to a narrow heath between Green Lane and the Coventry Road, where the baths and library were built later.[1] The 1799 opening of the Warwick and Birmingham Canal (now the Grand Union Canal), from Digbeth to Warwick, defined the southern edge of this scattered rural community.[1] In 1852, this definition was enforced with the opening of the Isambard Kingdom Brunel designed Birmingham and Oxford Junction Railway, which follows the same route.[1]

As Birmingham developed, the wealthy began to look for space outside the crowded inner city. Small Heath, a green site close to and within a fast developing city, began to be developed from 1834 when large houses first appeared east of the Small Heath between Green Lane and Grange Road. The next developments were mainly terraced housing estates laid out for the working classes as far as Charles Road.[1]

Muntz Street

[edit]

The development of properties in the area was made much easier and cheaper through the extraction of the local clay, which was then locally turned into bricks. The largest local clay pit was on Cattell Road.[1]

Members of Holy Trinity Cricket Club, Bordesley had formed the Small Heath Alliance Football Club in 1875 as a way of keeping fit over the winter. After playing in Bordesley Green and Sparkbrook, in 1877 they moved to what became called the Muntz Street stadium, which rented for an initial £5 a year from the family of Sam Jessey, a Small Heath player.[2] The field had a capacity of 10,000 spectators and was bordered on two sides by developed streets, Muntz Street on the western side, Wright Street to the south; the other two sides of the enclosure adjoined farmland.[A]

Also serving as the headquarters of the Small Heath Athletic Club, the initial capacity was raised by the addition of a wooden stand and the terracing raised to expand the capacity to around 30,000. In 1895, the football club bought the lease to the ground, which had 11 years remaining, for a sum of £275.[3]

Small Heath Athletic Club (later called Small Heath Harriers) established its headquarters at the Muntz Street ground from the club's foundation in 1891. Though primarily a cross-country and road-racing club, they also participated in track and field athletics, and during the summer months the athletes were allowed to train on the football pitch.[4] Birmingham received its city charter in 1889, the club was renamed Birmingham City Football Club in 1943.[5]

Eventually the ground proved too small for the football club's needs, and rising rents forced the development of a new stadium. The club built a new stadium nearer the city centre, St Andrew's. The last game at Muntz Street was played on 22 December 1906, when Birmingham beat Bury 3–1 in the First Division in front of some 10,000 spectators.[6] St. Andrews hosted its first game in December 1906. Within months the Muntz Street had been demolished, the land cleared and housing built in what became Swanage Road;[7] no plaque commemorates the site, but the street of the same name remains.[2][8]

World War II

[edit]By the outbreak of World War II, BSA Guns Ltd at Small Heath was the only factory producing rifles in the UK. The Royal Ordnance Factories would not begin production until 1941. BSA Guns Ltd was also producing .303 Browning machine guns for the Air Ministry at the rate of 600 guns per week in March 1939 and Browning production was to peak at 16,390 per month by March 1942. The armed forces had chosen the 500 cc side-valve BSA M20 motorcycle as their preferred machine. On the outbreak of war, the Government requisitioned the 690 machines BSA had in stock as well as placing an order for another 8,000 machines. South Africa, Ireland, India, Sweden, and the Netherlands also wanted machines.

The Government passed the Emergency Powers (Defence) Act 1939 on 24 August allowing the drafting of defence regulations affecting food, travel, requisitioning of land and supplies, manpower and agricultural production. A second Emergency Powers (Defence) Act was passed on 22 May 1940 allowing the conscription of labour. The fall of France had not been anticipated in Government planning and the encirclement of a large part of the British Expeditionary Force into the Dunkirk pocket resulted in a hasty evacuation of that part of the B.E.F following the abandonment of their equipment. The parlous state of affairs "no arms, no transport, no equipment" in the face of the threat of imminent invasion of Britain by Nazi forces was recorded by the Chief of the Imperial General Staff Field Marshal Sir Alan Brooke, 1st Viscount Alanbrooke in his diary entries of the 1/2 July 1940.[9]

The creation of the Home Guard (initially as the Local Defence Volunteers) following Anthony Eden's broadcast appeal to the Nation on Tuesday 14 May 1940 also created further demand for arms production to equip this new force. BSA, as the only rifle producer in Britain, had to step up to the mark and the workforce voluntarily went onto a seven-day week.[10] Motorcycle production was also stepped up from 500 to 1,000 machines per week which meant a finished machine coming off the production line every 5 minutes. The motorcycle department workforce had been left intact in 1939 due to demand which was doubled following Dunkirk. At the same time BSA staff were providing lectures and demonstrations on motorcycle riding and maintenance to 250,000 officers and men in all parts of the UK.

The BSA factory at Small Heath was bombed by the Luftwaffe on 26 August 1940 resulting in one H.E.bomb and a shower of incendiaries hitting the main barrel mill, the only one operating on service rifles in the country, thereby causing the unaffordable loss of 750 machine tools but no loss of life.[11] Two further air raids took place on 19 and 22 November 1940.[12] The air raid of 19 November did the most damage, causing loss of production and trapping hundreds of workers. Two BSA night-shift electricians, Alf Stevens and Alf Goodwin helped rescue their fellow workers. Alf Stevens was awarded the George Medal for his selfless acts of bravery in the rescue and Alf Goodwin was awarded the British Empire Medal. Workers involved in the works Civil Defence were brought in to help search for and clear bodies to get the plant back into production. The net effect of the November raids was to destroy machine shops in the four-storey 1915 building, the original 1863 gunsmiths' building and nearby buildings, 1,600 machine tools, kill 53 employees and another 50+ local residents, injured 89 (30 of them seriously), and halted rifle production for three months. The Government Ministry of Supply and BSA immediately began a process of production dispersal throughout Britain, through the shadow factory scheme.

Geography

[edit]Business

[edit]

There are two large supermarkets, Asda and Morrisons and the outdoor pursuits centre Ackers Trust. There is also a business park that is home to the former Birmingham Cable Company (now Virgin Media), the international CADCAM company Delcam and kitchen appliance repair specialists Repaircare. In recent years, the Coventry Road has attracted a growing increasing number of ethnic fast food restaurants.[citation needed]

Until 1973, Small Heath was the home of the massive Birmingham Small Arms factory on Golden Hillock Road and Armoury Road, manufacturing amongst other things, bicycles, motorcycles, guns and cars including taxi cabs, dominating the local and national economy. The factory was briefly acquired by Norton Villiers Triumph following their takeover of BSA but closed down, much of it being demolished following the collapse of the British motorcycle industry. A business park now occupies the site whilst the remaining buildings are still used for manufacturing.

On Coventry Road, many Middle Eastern and South Asian restaurants have opened, serving traditional Lebanese, Syrian, Yemeni and Pakistani dishes. Arabian cafes and supermarkets have also opened up in the area.

Housing

[edit]Many mostly terraced houses were built around Small Heath towards the end of the 19th century, and over the next few decades these buildings became the residence of numerous Irish immigrants. In the 20 or so years that followed the end of World War II, the area attracted more immigrants – mostly from the Indian sub-continent. Immigrants from the West Indies also settled in Small Heath, but Pakistani immigrants, including a large majority from Azad Kashmir, were by far the most significant people to settle in the area. House prices have been steadily increasing on a par with other areas within Birmingham.

Population

[edit]The total population of the area is approximately 36,898, based on 2007 estimates.[13] The majority of residents are of South Asian origin, mainly of Pakistani (51%) while people of White British ethnicity form 22% of the population. There are also many East African residents from Somalia, Sudan and Eritrea who live in Small Heath.[14] The majority[citation needed] of residents are also Muslim; and there are many mosques in the area, the largest in Small Heath being the Ghamkol Shariff Masjid which is also one of the largest in the UK.[citation needed]

The district is well known for its extremely diverse Muslim community and shopping centres within one of the busiest street in Birmingham, Coventry road, home to large mosques within a proximity to each other and restaurants serving Halal food and goods mainly more busy during Ramadan. In the road you find a melting pot of a large East African presence (mostly Somali and Sudanese) with chains like Dahabshill as well as Yemeni restaurants and Kashmiri street food.

Parks and sport

[edit]There are several parks and green spaces in the suburb, of which the largest (Small Heath Park – formerly known as Victoria Park) occasionally hosts festivals. An episode of Charlie's Garden Army featured a permanent installation in Small Heath Park. Small Heath is home to Birmingham City Football Club's St. Andrews stadium.

Transport

[edit]The section of Coventry Road running through Small Heath formed part of the main A45 route from Birmingham to Coventry, until bypassed to the south by a dual carriageway opened in January 1985.

It is served by Small Heath railway station on the North Warwickshire Line. The Grand Union Canal also passes through the area. Local transport connections are very good, with a mainline railway station and many bus routes to other parts of the city. The 60 bus (operated by National Express West Midlands) serves Small Heath and runs from the city centre of Birmingham along Coventry Road, heading towards Cranes Park. Furthermore, the 8C Inner Circle also travels through the area, along with the 27 that passes the Birmingham City stadium, before heading towards Bordesley Green along Green Lane.

In the early years, horse-drawn buses ran along the Coventry Road, linking Small Heath with the city centre and with other nearby districts. In 1882, the building of a tramline along the Coventry Road to Small Heath Park was authorised, and four years later, the Coventry Road steam tramway route was opened to a terminus near Dora Road. In the early years of the 20th century, this line was converted for use by electric trams.[15]

Politics

[edit]Small Heath is part of the Birmingham Hodge Hill and Solihull North constituency (formerly Birmingham Hodge Hill, until 2024), which is held by Labour MP Liam Byrne. The constituency has a high proportion of people of South Asian and Middle Eastern origin, and this section of the community has historically supported the Labour Party but in recent years the Conservatives and Liberals Democrats have increased in votes. In the recent years, residents have shown their frustration with Labour for not listening to residents concerns. Saqib Khan and Shabina Bano are the current councillors for the ward, they were elected in 2022.

People from Small Heath

[edit]- Matthew Edwards, singer and songwriter, active from 1980's to the present[16]

- Jaykae, rapper born and raised in Small Heath

- Peaky Blinders, gang founded in Small Heath

- Thomas Gilbert, leader of the Peaky Blinders

- David Harewood OBE. British actor and presenter was born in Small Heath.

- Rowland Emett OBE. Famous British cartoonist.

- Ken Barnes English footballer born in Small Heath played for Wrexham and Manchester City. FA cup winner with Manchester City.

- George Allen Born in Small Heath, Allen was an English footballer who played more than 250 games in the Football League. He played for Coventry City and Birmingham City.

- Wilfred Emmanuel-Jones businessman, farmer and unsuccessful Conservative Party candidate who grew up in Small Heath.

- Shabana Mahmood is the Labour MP for Birmingham Ladywood. Mahmood was born in Birmingham and grew up in the Small Heath area and attended Small Heath comprehensive school.

- Ayaz Khan, one of three Labour politicians sacked for notorious postal voting fraud.

- Shafique Shah, Lord Mayor of Birmingham and Deputy Lord Mayor.

- Gerry Summers born in Small Heath, summers was a football player with West Bromwich Albion, Sheffield United, Hull City and Walsall.

- John Carter is an English singer, songwriter, and record producer. The Small Heath-born artist was mainly popular in the 1960s and early 1970s.

- Wasim Khan MBE is a former British cricketer who was the first player of Pakistani and Kashmiri origin to play professional cricket in England. In 2022, Khan became the general manager of the ICC.

In popular culture

[edit]In the BBC One series Peaky Blinders, Small Heath is the home base of the Shelbys and core members of their gang, the Peaky Blinders.[17][18]

The BBC Three series Man Like Mobeen is set in Small Heath, with references to Smethwick.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h "Small Heath". Bill Dargue. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- ^ a b Beauchampé, Steve (26 December 2006). "100 years of St. Andrews – Part One". The Stirrer. Retrieved 4 February 2009.

- ^ Jawad, Hyder (2006). Keep Right On. The Official Centenary Of St. Andrew's. Liverpool: Trinity Mirror Sport Media. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-905266-16-6.

- ^ "History: Small Heath Harriers". Solihull and Small Heath Athletic Club. Retrieved 25 November 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Matthews, Tony (October 2000). The Encyclopedia of Birmingham City Football Club 1875–2000. Cradley Heath: Britespot. ISBN 978-0-9539288-0-4.

- ^ "Birmingham Again Victorious". Birmingham Daily Post. 24 December 1905.

- ^ Inglis, Simon (1996) [1985]. Football Grounds of Britain (3rd ed.). London: CollinsWillow. ISBN 0-00-218426-5.

- ^ "Historical plaques in Birmingham, United Kingdom". Open Plaques. Open Heritage C.I.C. Retrieved 5 April 2012.

- ^ War Diaries 1939 -1945 Field Marshal Lord Alanbrooke, London 2001, ISBN 0-297-60731-6

- ^ BSA Centenary 1861 – 1961, BSA Group News, No.17 June 1961, The Birmingham Small Arms Company, no ISBN

- ^ BSA Centenary 1861 – 1961, BSA Group News, No. 17 June 1961, The Birmingham Small Arms Company, no ISBN

- ^ Godwin, Tommy It wasn't that easy – The Tommy Godwin story, John Pinkerton Memorial Publishing Fund, 2007, ISBN 978-0-9552115-5-3

- ^ Resident Population Estimates by Broad Age Band – Small Heath Neighbourhood Statistics (ONS). Retrieved on 2009-06-24.

- ^ Ethnic Group – Small Heath Neighbourhood Statistics (ONS). Retrieved on 2009-06-24.

- ^ Hardy, P. L. (1972). "A transport history of Yardley". Acocks Green Historical Society. Archived from the original on 6 October 2007.

- ^ Toland, Michael (5 June 2019). "Matthew Edwards & the Unfortunates - The Birmingham Poets (December Square)". The Big Takeover. Retrieved 2 December 2023.

- ^ Lockley, Mike (28 September 2013). "Peaky Blinders pub could be yours for £175,000". Birmingham Mail.

- ^ Bradley, Michael (12 September 2013). "Birmingham's real Peaky Blinders". BBC News. West Midlands.