Wannsee Conference

| Wannsee Conference | |

|---|---|

The villa Am Großen Wannsee 56–58, where the Wannsee Conference was held, is now a memorial and museum. | |

| |

| Also known as | Wannseekonferenz |

| Location | Wannsee, Germany 52°25′59″N 013°09′56″E / 52.43306°N 13.16556°E |

| Date | 20 January 1942 |

| Participants | See: List of attendees |

The Wannsee Conference (German: Wannseekonferenz, German pronunciation: [ˈvanzeːkɔnfeˌʁɛnt͡s] ) was a meeting of senior government officials of Nazi Germany and Schutzstaffel (SS) leaders, held in the Berlin suburb of Wannsee on 20 January 1942. The purpose of the conference, called by the director of the Reich Security Main Office SS-Obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich, was to ensure the co-operation of administrative leaders of various government departments in the implementation of the Final Solution to the Jewish Question, whereby most of the Jews of German-occupied Europe would be deported to occupied Poland and murdered. Conference participants included representatives from several government ministries, including state secretaries from the Foreign Office, the justice, interior, and state ministries, and representatives from the SS. In the course of the meeting, Heydrich outlined how European Jews would be rounded up and sent to extermination camps in the General Government (the occupied part of Poland), where they would be killed.[1]

Discrimination against Jews began immediately after the Nazi seizure of power on 30 January 1933. Violence and economic pressure were used by the Nazi regime to encourage Jews to voluntarily leave the country. After the invasion of Poland in September 1939, the extermination of European Jews began, first through mobile death squads like the Einsatzgruppen, and the killings continued and accelerated after the invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941. On 31 July 1941, Hermann Göring gave written authorization to Heydrich to prepare and submit a plan for a "total solution of the Jewish question" in territories under German control and to coordinate the participation of all involved government organisations. At the Wannsee Conference, Heydrich emphasised that once the deportation process was complete, the fate of the deportees would become an internal matter under the purview of the SS. A secondary goal was to arrive at a definition of who was Jewish.

One copy of the Protocol with circulated minutes of the meeting survived the war. It was found by Robert Kempner in March 1947 among files that had been seized from the German Foreign Office. It was used as evidence in the subsequent Nuremberg trials. The Wannsee House, site of the conference, is now a Holocaust memorial.

Background

[edit]Legalized discrimination against Jews in Germany began immediately after the Nazi seizure of power in January 1933. The ideology of Nazism brought together elements of antisemitism, racial hygiene, and eugenics and combined them with pan-Germanism and territorial expansionism with the goal of obtaining more Lebensraum (living space) for the Germanic people.[2] Nazi Germany attempted to obtain this new territory by invading Poland and the Soviet Union, intending to deport or exterminate the Jews and Slavs living there, who were viewed as being inferior to the Aryan master race.[3]

Discrimination against Jews, long-standing but extra-legal throughout much of Europe at the time, was codified in Germany immediately after the Nazi seizure of power on 30 January 1933. The Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service, passed on 7 April of that year, excluded most Jews from the legal profession and the civil service. Similar legislation soon deprived other Jews of the right to practise their professions.[4] Violence and economic pressure were used by the regime to force Jews to leave the country.[5] Jewish businesses were denied access to markets, forbidden to advertise in newspapers, and deprived of access to government contracts. Citizens were harassed and subjected to violent attacks and boycotts of their businesses.[6]

In September 1935, the Nuremberg Laws were enacted, prohibiting marriages between Jews and people of Germanic extraction, extramarital sexual relations between Jews and Germans, and the employment of German women under the age of 45 as domestic servants in Jewish households.[7] The Citizenship Law stated that only those of German or related blood were defined as citizens; thus, Jews and other minority groups were stripped of their German citizenship.[8] A supplementary decree issued in November defined as Jewish anyone with three Jewish grandparents, or two grandparents if the Jewish faith was followed.[9] By the start of World War II in Europe in 1939, around 250,000 of Germany's 437,000 Jews had emigrated to the United States, British Mandatory Palestine, Great Britain, and other countries.[10][11]

After the invasion of Poland in September 1939, Hitler ordered that the Polish leadership and intelligentsia be destroyed.[12] The Sonderfahndungsbuch Polen (Special Ledger of Wanted Persons–Poland)[a]—lists of people to be located so they could be interned or killed—had been drawn up by the SS as early as May 1939.[12] The Einsatzgruppen (special task forces) performed these murders with the support of the Volksdeutscher Selbstschutz (Germanic Self-Protection Group), a paramilitary group consisting of ethnic Germans living in Poland.[14] Members of the SS, the Wehrmacht (German Armed Forces), and the Ordnungspolizei (Order Police; Orpo) also shot civilians during the Polish campaign.[15] Approximately 65,000 civilians were killed by the end of 1939. In addition to leaders of Polish society, they killed Jews, prostitutes, Romani people, and the mentally ill.[16][17]

On 31 July 1941, Hermann Göring gave written authorization to SS-Obergruppenführer (Senior Group Leader) Reinhard Heydrich, Chief of the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA), to prepare and submit a plan for a "total solution of the Jewish question" in territories under German control and to coordinate the participation of all involved government organisations.[18] The resulting Generalplan Ost (General Plan for the East) called for deporting the population of occupied Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union to Siberia, for use as slave labour or to be murdered.[19] The minutes of the Wannsee Conference estimated the Jewish population of the Soviet Union to be five million, including nearly three million in Ukraine.[20]

In addition to eliminating Jews, the Nazis also planned to reduce the population of the conquered territories by 30 million people through starvation in an action called the Hunger Plan devised by Herbert Backe.[21] Food supplies would be diverted to the German army and German civilians. Cities would be razed and the land allowed to return to forest or resettled by German colonists.[22] The objective of the Hunger Plan was to inflict deliberate mass starvation on the Slavic civilian populations under German occupation by directing all food supplies to the German home population and the Wehrmacht on the Eastern Front.[23] According to the historian Timothy Snyder, "4.2 million Soviet citizens (largely Russians, Belarusians, and Ukrainians) were starved" by the Nazis (and the Nazi-controlled Wehrmacht) in 1941–1944 as a result of Backe's plan.[24][25]

Harvests were poor in Germany in 1940 and 1941 and food supplies were short, as large numbers of forced labourers had been brought into the country to work in the armaments industry.[26] If these workers—as well as the German people—were to be adequately fed, there must be a sharp reduction in the number of "useless mouths", of whom the millions of Jews under German rule were, in the light of Nazi ideology, the most obvious example.[27]

At the time of the Wannsee Conference, the killing of Jews in the Soviet Union had already been underway for some months. Right from the start of Operation Barbarossa—the invasion of the Soviet Union—Einsatzgruppen were assigned to follow the army into the conquered areas and round up and kill Jews. In a letter dated 2 July 1941, Heydrich communicated to his SS and police leaders that the Einsatzgruppen were to execute Comintern officials, ranking members of the Communist Party, extremist and radical Communist Party members, people's commissars, and Jews in party and government posts.[28] Open-ended instructions were given to execute "other radical elements (saboteurs, propagandists, snipers, assassins, agitators, etc.)".[28] He instructed that any pogroms spontaneously initiated by the occupants of the conquered territories were to be quietly encouraged.[28] On 8 July, he announced that all Jews were to be regarded as partisans, and gave the order for all male Jews between the ages of 15 and 45 to be shot.[29] By August, the net had been widened to include women, children, and the elderly—the entire Jewish population.[30] By the time planning was underway for the Wannsee Conference, hundreds of thousands of Polish, Serbian, and Russian Jews had already been killed.[31] The initial plan was to implement Generalplan Ost after the conquest of the Soviet Union.[19][32] European Jews would be deported to occupied parts of Russia, where they would be worked to death in road-building projects.[31]

Planning the conference

[edit]

On 29 November 1941, Heydrich sent invitations for a ministerial conference to be held on 9 December at the offices of Interpol at Am Kleinen Wannsee 16.[33] He changed the venue on 4 December to the eventual location of the meeting.[33] He enclosed a copy of a letter from Göring dated 31 July that authorised him to plan a so-called Final Solution to the Jewish Question.[34] The ministries to be represented were those responsible for Jewish issues, including the Reich Chancellery, the Foreign Office, Interior, Justice, Propaganda, the Four Year Plan, and the Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories. Representatives from Party and SS components with special interests in the race issue were invited, including the Party Chancellery, the SS Race and Settlement Main Office, and the Office of the Reich Commissioner for the Consolidation of German Nationhood (RKFDV). Representatives from the General Government of occupied Poland were also added to the list.[35]

Between the date the invitations to the conference went out (29 November) and the date of the cancelled first meeting (9 December), the situation changed. On 5 December 1941, the Red Army began a counter-offensive in front of Moscow ending the prospect of a rapid conquest of the Soviet Union. On 7 December 1941, the Japanese carried out an attack on Pearl Harbor, causing the U.S. to declare war on Japan the next day. Germany declared war on the U.S. on 11 December. Some invitees were involved in these preparations, so Heydrich postponed his meeting.[36] Somewhere around this time, Hitler resolved that the Jews of Europe were to be exterminated immediately, rather than after the war, which now had no end in sight.[37][b] At the Reich Chancellery meeting of 12 December 1941 he met with top party officials and made his intentions plain.[38] On 18 December, Hitler discussed the fate of the Jews with Himmler in the Wolfsschanze.[39] Following the meeting, Himmler made a note on his service calendar, which simply stated: "Jewish question/to be destroyed as partisans".[39]

The original intention was to deport the Jews to camps in occupied areas of the Soviet Union and kill them there, but because victory over the Soviet Union was not forthcoming, the plans had to be changed. Heydrich decided that the Jews currently living in the General Government (the German-occupied area of Poland) would be killed in extermination camps set up in occupied areas of Poland, as would Jews from the rest of Europe.[1]

On 8 January 1942, Heydrich sent new invitations to a meeting to be held on 20 January.[40] The venue for the rescheduled conference was a villa at Am Großen Wannsee 56–58, overlooking the Großer Wannsee. The villa had been purchased from Friedrich Minoux in 1940 by the Sicherheitsdienst (Security Force; SD) for use as a conference centre and guest house.[41]

Attendees

[edit]The attendees from the Reich civilian ministries were high level administrators. Most were either the state secretary or an undersecretary. With the cabinet not meeting regularly, meetings between the state secretaries were the chief means of policy coordination among agencies.[33] The process of disseminating information about the fate of the Jews was already well underway by the time the meeting was held, and several of the attendees were aware that changes to the Jewish policy were already underway.[42] In addition to the invited guests, Heydrich instructed several SS officials from his RSHA component to attend.[43] In all, 15 officials attended the conference.[c] Half the attendees were under forty years of age and only two were over fifty.[44] They were well educated, with ten having a university education (of whom eight held academic doctorates), and eight were lawyers.[45]

| Name | Photo | Title | Organization | Superior |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SS-Obergruppenführer (Lieutenant General) Reinhard Heydrich |

|

Chief of the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA) Deputy Protector of Bohemia and Moravia Deputy Reichsführer-SS |

RSHA, Schutzstaffel (SS) | Reichsführer-SS (SS-Leader) Heinrich Himmler |

| SS-Gruppenführer (Major General) Otto Hofmann |

|

Head of the SS Race and Settlement Main Office (RuSHA) | RuSHA, Schutzstaffel | Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler |

| SS-Gruppenführer (Major General) Heinrich Müller |

|

Chief of Amt IV (Gestapo) | RSHA, Schutzstaffel | Chief of the RSHA SS-Obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich |

| SS-Oberführer (Senior Colonel) Karl Eberhard Schöngarth |

|

Commander of the SiPo and the SD in the General Government | SiPo and SD, RSHA, Schutzstaffel | Chief of the RSHA SS-Obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich |

| SS-Oberführer (Senior Colonel) Gerhard Klopfer |

|

Permanent Secretary | Nazi Party Chancellery | Chief of the Party Chancellery Martin Bormann |

| SS-Obersturmbannführer (Lieutenant Colonel) Adolf Eichmann |

|

Head of Referat IV B4 of the Gestapo Recording secretary |

Gestapo, RSHA, Schutzstaffel | Chief of Amt IV SS-Gruppenführer Heinrich Müller |

| SS-Sturmbannführer (Major) Rudolf Lange |

|

Commander of the SiPo and the SD for Latvia; Deputy Commander of the SiPo and the SD for the Reichskommissariat Ostland (RKO); Head of Einsatzkommando 2 |

SiPo and SD, RSHA, Schutzstaffel | Commander of the SiPo and the SD for the RKO, SS-Brigadeführer (Brigadier General) and Generalmajor der Polizei (Brigadier General of Police) Franz Walter Stahlecker |

| Georg Leibbrandt |

|

Undersecretary | Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories | Minister for the Occupied Eastern Territories Alfred Rosenberg |

| Alfred Meyer |

|

Gauleiter (Regional Party Leader) State Secretary and Deputy Minister |

Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories | Minister for the Occupied Eastern Territories Alfred Rosenberg |

| Josef Bühler |

|

State Secretary | General Government (Polish Occupation Authority) |

Governor-General Hans Frank |

| Roland Freisler |

|

State Secretary | Ministry of Justice | Minister of Justice Franz Schlegelberger |

| SS-Brigadeführer (Brigadier General) Wilhelm Stuckart |

|

State Secretary | Interior Ministry | Minister of the Interior Wilhelm Frick |

| SS-Oberführer (Senior Colonel) Erich Neumann |

|

State Secretary | Office of the Plenipotentiary for the Four Year Plan | Plenipotentiary of the Four Year Plan Hermann Göring |

| Friedrich Wilhelm Kritzinger |

|

Permanent Secretary | Reich Chancellery | Minister and head of the Reich Chancellery SS-Obergruppenführer Hans Lammers |

| Martin Luther |

|

Undersecretary | Foreign Office | Ernst von Weizsäcker, State Secretary to Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop |

Proceedings

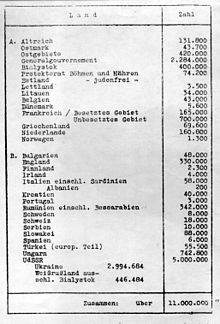

[edit]In preparation for the conference, Eichmann drafted a list of the total numbers of Jews in the various European countries. Countries were listed in two groups, "A" and "B". "A" countries were those under direct German control or occupation (or partially occupied and quiescent, in the case of Vichy France); "B" countries were allied or client states, neutral, or at war with Germany.[46][d] The numbers reflect the estimated Jewish population within each country; for example, Estonia is listed as Judenfrei (free of Jews), since the 4,500 Jews who remained in Estonia after the German occupation had been killed by the end of 1941.[47] Occupied Poland was not on the list because by 1939 the country was split three ways among Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany in the west, the territories of Poland annexed by the Soviet Union in the east, and the General Government where many Polish and Jewish expellees had already been resettled.[48]

Heydrich opened the conference with an account of the anti-Jewish measures taken in Germany since the Nazi seizure of power in 1933. He said that between 1933 and October 1941, 537,000 German, Austrian, and Czech Jews had emigrated.[49] This information was taken from a briefing paper prepared for him the previous week by Eichmann.[50]

Heydrich reported that there were approximately eleven million Jews in the whole of Europe, of whom half were in countries not under German control.[46][d] He explained that since further Jewish emigration had been prohibited by Himmler, a new solution would take its place: "evacuating" Jews to the east. This would be a temporary solution, a step towards the "final solution of the Jewish question".[51]

Under proper guidance, in the course of the final solution the Jews are to be allocated for appropriate labor in the East. Able-bodied Jews, separated according to sex, will be taken in large work columns to these areas for work on roads, in the course of which action doubtless a large portion will be eliminated by natural causes. The possible final remnant will, since it will undoubtedly consist of the most resistant portion, have to be treated accordingly, because it is the product of natural selection and would, if released, act as the seed of a new Jewish revival.[52]

German historian Peter Longerich notes that vague orders couched in terminology that had a specific meaning for members of the regime were common, especially when people were being ordered to carry out criminal activities. Leaders were given briefings about the need to be "severe" and "firm"; all Jews were to be viewed as potential enemies that had to be dealt with ruthlessly.[53] The wording of the Wannsee Protocol—the distributed minutes of the meeting—made it clear to participants that evacuation east was a euphemism for death.[54]

Heydrich went on to say that in the course of the "practical execution of the final solution", Europe would be "combed through from west to east", but that Germany, Austria, and the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia would have priority, "due to the housing problem and additional social and political necessities".[52] This was a reference to increasing pressure from the Gauleiters (regional Nazi Party leaders) in Germany for the Jews to be removed from their areas to allow accommodation for Germans made homeless by Allied bombing, as well as to make space for laborers being imported from occupied countries. The "evacuated" Jews, he said, would first be sent to "transit ghettos" in the General Government, from which they would be transported eastward.[52] Heydrich said that to avoid legal and political difficulties, it was important to define who was a Jew for the purposes of "evacuation". He outlined categories of people who would not be killed. Jews over 65 years old, and Jewish World War I veterans who had been severely wounded or who had won the Iron Cross, might be sent to Theresienstadt concentration camp instead of being killed. "With this expedient solution", he said, "in one fell swoop, many interventions will be prevented."[52]

The situation of people who were half or quarter Jews, and of Jews who were married to non-Jews, was more complex. Under the Nuremberg Laws of 1935, their status had been left deliberately ambiguous. Heydrich announced that Mischlinge (mixed-race persons) of the first degree (persons with two Jewish grandparents) would be treated as Jews. This would not apply if they were married to a non-Jew and had children by that marriage. It would also not apply if they had been granted written exemption by "the highest offices of the Party and State".[55] Such persons would be sterilised or deported if they refused sterilisation.[55] A "Mischling of the second degree" (a person with one Jewish grandparent) would be treated as German, unless he or she was married to a Jew or a Mischling of the first degree, had a "racially especially undesirable appearance that marks him outwardly as a Jew",[56] or had a "political record that shows that he feels and behaves like a Jew".[57] Persons in these latter categories would be killed even if married to non-Jews.[56] In the case of mixed marriages, Heydrich recommended that each case should be evaluated individually, and the impact on any German relatives assessed. If such a marriage had produced children who were being raised as Germans, the Jewish partner would not be killed. If they were being raised as Jews, they might be killed or sent to an old-age ghetto.[57] These exemptions applied only to German and Austrian Jews, and were not always observed even for them. In most of the occupied countries, Jews were rounded up and killed en masse, and anyone who lived in or identified with the Jewish community in any given place was regarded as a Jew.[58][e]

Heydrich commented: "In occupied and unoccupied France, the registration of Jews for evacuation will in all probability proceed without great difficulty",[59] but in the end, the great majority of French-born Jews survived.[60] More difficulty was anticipated with Germany's allies Romania and Hungary. "In Romania the government has [now] appointed a commissioner for Jewish affairs", Heydrich said.[59] In fact the deportation of Romanian Jews was slow and inefficient despite a high degree of popular antisemitism.[61] "In order to settle the question in Hungary", Heydrich said, "it will soon be necessary to force an adviser for Jewish questions onto the Hungarian government".[59] The Hungarian regime of Miklós Horthy continued to resist German interference in its Jewish policy until the spring of 1944, when the Wehrmacht invaded Hungary. Very soon, Eichmann – with the collaboration of Hungarian authorities – would send 600,000 Jews of Hungary (and parts of Czechoslovakia, Romania, and Yugoslavia occupied by Hungary) to be murdered in the extermination camps, primarily Auschwitz.[62]

Heydrich spoke for nearly an hour. Then followed about thirty minutes of questions and comments, followed by some less formal conversation.[63] Otto Hofmann (head of the SS Race and Settlement Main Office; RuSHA) and Wilhelm Stuckart (State Secretary of the Interior Ministry) pointed out the legalistic and administrative difficulties over mixed marriages, and suggested compulsory dissolution of mixed marriages or the wider use of sterilisation as a simpler alternative.[64] Erich Neumann from the Four Year Plan argued for the exemption of Jews who were working in industries vital to the war effort and for whom no replacements were available. Heydrich assured him that this was already the policy; such Jews would not be killed.[65][f] Josef Bühler, State Secretary of the General Government, stated his support for the plan and his hope that the killings would commence as soon as possible.[66]

Towards the end of the meeting cognac was served, and after that the conversation became less restrained.[64] Eichmann said:

"The gentlemen were standing together, or sitting together and were discussing the subject quite bluntly, quite differently from the language which I had to use later in the record. During the conversation they minced no words about it at all ... they spoke about methods of killing, about liquidation, about extermination."[63]

Eichmann recorded that Heydrich was pleased with the course of the meeting. He had expected a lot of resistance, Eichmann recalled, but instead, he had found "an atmosphere not only of agreement on the part of the participants, but more than that, one could feel an agreement which had assumed a form which had not been expected".[58]

Eichmann's list

[edit]

|

|

|

Wannsee Protocol

[edit]

Shorthand notes for the minutes were taken by Eichmann's secretary, Ingeburg Werlemann, and the minutes were written by Eichmann in consultation with Heydrich.[67] At the conclusion of the meeting, Heydrich gave Eichmann firm instructions about what was to appear in the minutes. They were not to be verbatim: Eichmann ensured that nothing too explicit appeared in them. He said at his trial: "How shall I put it – certain over-plain talk and jargon expressions had to be rendered into office language by me."[66]

Eichmann condensed his records into a document outlining the purpose of the meeting and the intentions of the regime. He stated at his trial that it was personally edited by Heydrich, and thus reflected the message he intended the participants to take away from the meeting.[68] Copies of the minutes (known by the German word for "minutes" as the "Wannsee Protocol"[g]) were sent by Eichmann to all the participants after the meeting.[69] Most of these copies were destroyed at the end of the war as participants and other officials sought to cover their tracks. It was not until 1947 that Luther's copy (number 16 out of 30 copies prepared) was found by Robert Kempner, a U.S. prosecutor in the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg, in files that had been seized from the German Foreign Office.[70]

Interpretation

[edit]

The Wannsee Conference lasted only about ninety minutes. The enormous importance which has been attached to the conference by post-war writers was not evident to most of its participants at the time. Heydrich did not call the meeting to make fundamental new decisions on the Jewish question; massive killings of Jews in the conquered territories in the Soviet Union and Poland were ongoing. A new extermination camp was under construction at Belzec at the time of the conference, and other extermination camps were in the planning stages.[31][71] The decision to exterminate the Jews had already been made, and Heydrich, as Himmler's emissary, held the meeting to ensure the cooperation of the various departments in conducting the deportations.[72] Observations from historian Laurence Rees support Longerich's position that the decision over the fate of the Jews was determined before the conference; Rees notes that the Wannsee Conference was really a meeting of "second-level functionaries", and stresses that Himmler, Goebbels, and Hitler were not present.[73] According to Longerich, a primary goal of the meeting was to emphasise that once the deportations had been completed, the fate of the deportees became an internal matter of the SS, totally outside the purview of any other agency.[74] A secondary goal was to determine the scope of the deportations and arrive at definitions of who was Jewish and who was Mischling.[74] "The representatives of the ministerial bureaucracy had made it plain that they had no concerns about the principle of deportation per se. This was indeed the crucial result of the meeting and the main reason why Heydrich had detailed minutes prepared and widely circulated", said Longerich.[75] Their presence at the meeting also ensured that all those present were accomplices and accessories to the murders that were about to be undertaken.[76]

Eichmann's biographer David Cesarani agrees with Longerich's interpretation; he notes that Heydrich's main purpose was to impose his own authority on the various ministries and agencies involved in Jewish policy matters, and to avoid any repetition of the objections to the deportations and genocide from his military and civilian subordinates that had occurred earlier in the annihilation campaign. "The simplest, most decisive way that Heydrich could ensure the smooth flow of deportations", he writes, "was by asserting his total control over the fate of the Jews in the Reich and the east, and [by] cow[ing] other interested parties into toeing the line of the RSHA".[77]

House of the Wannsee Conference

[edit]In 1965, historian Joseph Wulf proposed that the Wannsee House should be made into a Holocaust memorial and document centre, but the West German government was not interested at that time. The building was in use as a school, and funding was not available. Despondent at the failure of the project, and at the West German government's failure to pursue and convict Nazi war criminals, Wulf committed suicide in 1974.[78]

On 20 January 1992, on the fiftieth anniversary of the conference, the site was finally opened as a Holocaust memorial and museum known as the Haus der Wannsee-Konferenz (House of the Wannsee Conference).[79] The museum also hosts permanent exhibits of texts and photographs that document events of the Holocaust and its planning.[80] The Joseph Wulf Bibliothek / Mediothek on the second floor houses a large collection of books on the Nazi era, plus other materials such as microfilms and original Nazi documents.[80]

See also

[edit]- The Wannsee Conference – 1984 German-language TV film

- Fatherland – 1992 alternate history novel dealing in large part with the Wannsee Conference

- Fatherland – 1994 film adaptation of the homonymous novel.

- Conspiracy – 2001 English-language film

- Die Wannseekonferenz – 2022 German-language TV film

- Bibliography of the Holocaust § Primary sources

Notes

[edit]- ^ Robert Michael and Karen Doerr, authors of Nazi-Deutsch/Nazi German: An English Lexicon of the Language of the Third Reich, translate the term Sonderfahndungsbuch to "Special Tracing Book".[13]

- ^ German historian Christian Gerlach has claimed that Hitler approved the policy of extermination in a speech to senior officials in Berlin on 12 December. Gerlach 1998, p. 785. This date is not universally accepted, but it seems likely that a decision was made at around this time. On 18 December, Himmler met with Hitler and noted in his appointment book: "Jewish question – to be exterminated as partisans". Browning 2007, p. 410. On 19 December, Wilhelm Stuckert, State Secretary at the Interior Ministry, told one of his officials: "The proceedings against the evacuated Jews are based on a decision from the highest authority. You must come to terms with it." Browning 2007, p. 405.

- ^ The invited representatives of two agencies were absent: Leopold Gutterer, State Secretary of the Propaganda Ministry, and Ulrich Greifelt, chief of staff of the RKFDV.Gerlach 1998, p. 794.

- ^ a b This information was contained in the briefing paper Eichmann prepared for Heydrich before the meeting. Cesarani 2005, p. 112.

- ^ At a meeting of 17 ministerial representatives held at the Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories on 29 January, it decided that in the eastern territories, all Mischlings were to be classed as Jews, while in western Europe, the relatively more lenient German standard would be applied. Browning 2007, p. 414.

- ^ Göring and his subordinates made persistent efforts to prevent skilled Jewish workers whose labour was an important part of the war effort from being killed. But by 1943, Himmler was a much more powerful figure in the regime than Göring, and all categories of skilled Jews eventually lost their exemptions. Tooze 2006, pp. 522–529.

- ^ The minutes are headed Besprechungsprotokoll (discussion minutes).

References

[edit]- ^ a b Longerich 2010, pp. 309–310.

- ^ Evans 2008, p. 7.

- ^ Longerich 2010, p. 132.

- ^ Longerich 2010, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Longerich 2010, pp. 67–69.

- ^ Longerich 2010, p. 41.

- ^ Kershaw 2008, p. 346.

- ^ Evans 2005, p. 544.

- ^ Kershaw 2008, p. 347.

- ^ Longerich 2010, p. 127.

- ^ Evans 2005, p. 555.

- ^ a b Longerich 2010, p. 144.

- ^ Michael & Doerr 2002, p. 377.

- ^ Longerich 2010, pp. 144–145.

- ^ Longerich 2012, p. 429.

- ^ Evans 2008, p. 15.

- ^ Longerich 2012, pp. 430–432.

- ^ Browning 2007, p. 315.

- ^ a b Snyder 2010, p. 416.

- ^ Roseman 2002, p. 112.

- ^ Tooze 2006, pp. 476–486, 538–549.

- ^ Snyder 2010, pp. 162–163, 416.

- ^ Tooze 2006, p. 669.

- ^ Snyder 2010, p. 411.

- ^ Gerhard 2009.

- ^ Tooze 2006, p. 539.

- ^ Tooze 2006, pp. 538–549.

- ^ a b c Longerich 2012, p. 523.

- ^ Longerich 2010, p. 198.

- ^ Longerich 2010, p. 207.

- ^ a b c Longerich 2010, p. 309.

- ^ Kershaw 2008, p. 683.

- ^ a b c Roseman 2002, p. 57.

- ^ Browning 2007, p. 406.

- ^ Roseman 2002, pp. 58–59.

- ^ Browning 2007, p. 407.

- ^ Longerich 2000, p. 2.

- ^ Browning 2007, pp. 407–408.

- ^ a b Dederichs 2009, p. 119.

- ^ Browning 2007, p. 410.

- ^ Roseman 2002, p. 65.

- ^ Browning 2007, pp. 410–411.

- ^ a b Roseman 2002, p. 66.

- ^ Roseman 2002, p. 67.

- ^ Jasch & Kreutzmüller 2017, pp. 3, 180.

- ^ a b Roseman 2002, pp. 111–112.

- ^ Longerich 2010, pp. 237, 239.

- ^ Browning 2007, p. 93.

- ^ Roseman 2002, p. 110.

- ^ Cesarani 2005, p. 112.

- ^ Roseman 2002, pp. 110–111.

- ^ a b c d Roseman 2002, p. 113.

- ^ Longerich 2010, pp. 189–190.

- ^ Roseman 2002, p. 77.

- ^ a b Roseman 2002, p. 115.

- ^ a b Roseman 2002, pp. 115–116.

- ^ a b Roseman 2002, p. 116.

- ^ a b Browning 2007, p. 414.

- ^ a b c Roseman 2002, p. 114.

- ^ Marrus & Paxton 1981, pp. 343–344.

- ^ Cesarani 2005, pp. 151–155.

- ^ Cesarani 2005, pp. 159–195.

- ^ a b Browning 2007, p. 413.

- ^ a b Cesarani 2005, p. 113.

- ^ Roseman 2002, p. 71.

- ^ a b Cesarani 2005, p. 114.

- ^ Gryglewski 2020.

- ^ Roseman 2002, p. 68.

- ^ Cesarani 2005, pp. 117–118.

- ^ Roseman 2002, p. 1.

- ^ Breitman 1991, pp. 229–233.

- ^ Longerich 2010, p. 310.

- ^ Rees 2017, pp. 251–252.

- ^ a b Longerich 2000, p. 14.

- ^ Longerich 2010, pp. 306, 310.

- ^ Longerich 2000, p. 7.

- ^ Cesarani 2005, pp. 110–111.

- ^ Lehrer 2000, p. 134–135.

- ^ Wannsee House.

- ^ a b Lehrer 2000, p. 135.

Bibliography

[edit]- Breitman, Richard (1991). The Architect of Genocide: Himmler and the Final Solution. The Tauber Institute Series for the Study of European Jewry. Hanover, NH: Brandeis University Press. ISBN 978-0-87451-596-1.

- Browning, Christopher R. (2007) [2004]. The Origins of the Final Solution : The Evolution of Nazi Jewish Policy, September 1939 – March 1942. Comprehensive History of the Holocaust. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-0392-1.

- Cesarani, David (2005) [2004]. Eichmann: His Life and Crimes. London: Vintage. ISBN 978-0-099-44844-0.

- "Creation of the Memorial Site". Haus der Wannsee-Konferenz. Retrieved 14 October 2015.

- Dederichs, Mario (2009) [2006]. Heydrich: The Face of Evil. Casemate Publishers. ISBN 9781935149125.

- Evans, Richard J. (2005). The Third Reich in Power. New York: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-303790-3.

- Evans, Richard J. (2008). The Third Reich at War. New York: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-311671-4.

- Gerhard, Gesine (February 2009). "Food and Genocide. Nazi Agrarian Politics in the Occupied Territories of the Soviet Union". Contemporary European History. 18 (1): 57–62. doi:10.1017/S0960777308004827. S2CID 155045613.

- Gerlach, Christian (December 1998). "The Wannsee Conference, the Fate of German Jews, and Hitler's Decision in Principle to Exterminate All European Jews" (PDF). Journal of Modern History. 70 (4): 759–812. doi:10.1086/235167. S2CID 143904500.

- Gryglewski, Marcus (17 January 2020). "NS-Täterin auf der Wannseekonferenz: Eichmanns Sekretärin" [Nazi perpetrator at the Wannsee Conference: Eichmann's secretary]. Die Tageszeitung: Taz. taz.de. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- Jasch, Hans-Christian; Kreutzmüller, Christoph, eds. (2017). The Participants: The Men of the Wannsee Conference. New York: Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1-785-33671-3.

- Kershaw, Ian (2008). Hitler: A Biography. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-06757-6.

- Lehrer, Steven (2000). Wannsee House and the Holocaust. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-0792-7.

- Longerich, Peter (2000). "The Wannsee Conference in the Development of the 'Final Solution'" (PDF). Holocaust Educational Trust Research Papers. 1 (2). London: The Holocaust Educational Trust. ISBN 978-0-9516166-5-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2015.

- Longerich, Peter (2010). Holocaust: The Nazi Persecution and Murder of the Jews. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280436-5.

- Longerich, Peter (2012). Heinrich Himmler: A Life. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-959232-6.

- Marrus, Michael R.; Paxton, Robert O. (1981). Vichy France and the Jews. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-2499-9.

- Michael, Robert; Doerr, Karin (2002). Nazi-Deutsch/Nazi-German. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-32106-X.

- Rees, Laurence (2017). The Holocaust: A New History. New York: PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-1-61039-844-2.

- Roseman, Mark (2002). The Villa, The Lake, The Meeting: Wannsee and the Final Solution. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-71-399570-1. Published in the United States as The Wannsee Conference and the Final Solution: A Reconsideration. New York: Picador, 2002.

- Snyder, Timothy (2010). Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-00239-9.

- Tooze, Adam (2006). The Wages of Destruction: The Making and Breaking of the Nazi Economy. London; New York: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-713-99566-4.

Further reading

[edit]- Longerich, Peter (2022). Wannsee: The Road to the Final Solution. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198834045.

External links

[edit]- Official website of the House of the Wannsee Conference Educational and Memorial Site

- The Wannsee Conference on the Yad Vashem website

- Adolf Eichmann testifies about the Wannsee Conference on YouTube (in German with Japanese subtitles)

- Minutes from the Wannsee conference, archived by the Progressive Review

- Wannsee Conference at Traces of War website.