Wage

The examples and perspective in this article deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (July 2024) |

| Part of a series on |

| Economics |

|---|

|

A wage is payment made by an employer to an employee for work done in a specific period of time. Some examples of wage payments include compensatory payments such as minimum wage, prevailing wage, and yearly bonuses, and remunerative payments such as prizes and tip payouts. Wages are part of the expenses that are involved in running a business. It is an obligation to the employee regardless of the profitability of the company.

Payment by wage contrasts with salaried work, in which the employer pays an arranged amount at steady intervals (such as a week or month) regardless of hours worked, with commission which conditions pay on individual performance, and with compensation based on the performance of the company as a whole. Waged employees may also receive tips or gratuity paid directly by clients and employee benefits which are non-monetary forms of compensation. Since wage labour is the predominant form of work, the term "wage" sometimes refers to all forms (or all monetary forms) of employee compensation.

Origins and necessary components

[edit]Wage labour involves the exchange of money for time spent at work. As Moses I. Finley lays out the issue in The Ancient Economy:

- The very idea of wage-labour requires two difficult conceptual steps. First it requires the abstraction of a man's labour from both his person and the product of his work. When one purchases an object from an independent craftsman ... one has not bought his labour but the object, which he had produced in his own time and under his own conditions of work. But when one hires labour, one purchases an abstraction, labour-power, which the purchaser then uses at a time and under conditions which he, the purchaser, not the "owner" of the labour-power, determines (and for which he normally pays after he has consumed it). Second, the wage labour system requires the establishment of a method of measuring the labour one has purchased, for purposes of payment, commonly by introducing a second abstraction, namely labour-time.[1]

The wage is the monetary measure corresponding to the standard units of working time (or to a standard amount of accomplished work, defined as a piece rate). The earliest such unit of time, still frequently used, is the day of work. The invention of clocks coincided with the elaborating of subdivisions of time for work, of which the hour became the most common, underlying the concept of an hourly wage.[2][3]

Wages were paid in the Middle Kingdom of ancient Egypt,[4] ancient Greece,[5] and ancient Rome.[5] Following the unification of the city-states in Assyria and Sumer by Sargon of Akkad into a single empire ruled from his home city circa 2334 BC, common Mesopotamian standards for length, area, volume, weight, and time used by artisan guilds were promulgated by Naram-Sin of Akkad (c. 2254–2218 BC), Sargon's grandson, including shekels.[6] Codex Hammurabi Law 234 (c. 1755–1750 BC) stipulated a 2-shekel prevailing wage for each 60-gur (300-bushel) vessel constructed in an employment contract between a shipbuilder and a ship-owner.[7][8][9] Law 275 stipulated a ferry rate of 3-gerah per day on a charterparty between a ship charterer and a shipmaster. Law 276 stipulated a 21⁄2-gerah per day freight rate on a contract of affreightment between a charterer and shipmaster, while Law 277 stipulated a 1⁄6-shekel per day freight rate for a 60-gur vessel.[10][11][9]

Determinants of wage rates

[edit]Depending on the structure and traditions of different economies around the world, wage rates will be influenced by market forces (supply and demand), labour organisation, legislation, and tradition. Market forces are perhaps more dominant in the United States, while tradition, social structure and seniority, perhaps play a greater role in Japan.[12][citation needed]

Wage differences

[edit]Even in countries where market forces primarily set wage rates, studies show that there are still differences in remuneration for work based on sex and race. For example, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, in 2007 women of all races made approximately 80% of the median wage of their male counterparts. This is likely due to the supply and demand for women in the market because of family obligations.[13] Similarly, white men made about 84% the wage of Asian men, and black men 64%.[14] These are overall averages and are not adjusted for the type, amount, and quality of work done.

Effects

[edit]Corruption

[edit]It is known that the wage level of employees in the public sector affects the frequency of corruption, and that higher salary levels for public sector workers help reduce corruption. It has also been shown that countries with smaller wage gaps in the public sector have less corruption. [15]

Wages in the United States

[edit]

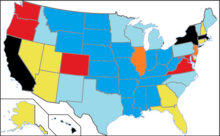

Seventy-five million workers earned hourly wages in the United States in 2012, making up 59% of employees.[16] In the United States, wages for most workers are set by market forces, or else by collective bargaining, where a labor union negotiates on the workers' behalf. The Fair Labor Standards Act establishes a minimum wage at the federal level that all states must abide by, among other provisions. Fourteen states and a number of cities have set their own minimum wage rates that are higher than the federal level. For certain federal or state government contacts, employers must pay the so-called prevailing wage as determined according to the Davis–Bacon Act or its state equivalent. Activists have undertaken to promote the idea of a living wage rate which account for living expenses and other basic necessities, setting the living wage rate much higher than current minimum wage laws require. The minimum wage rate is there to protect the well being of the working class.[17]

In the second quarter of 2022, the total U.S. labor costs grew up 5.2% year over year, the highest growth since the starting point of the serie in 2001.[19]

Definitions

[edit]For purposes of federal income tax withholding, 26 U.S.C. § 3401(a) defines the term "wages" specifically for chapter 24 of the Internal Revenue Code:

"For purposes of this chapter, the term “wages” means all remuneration (other than fees paid to a public official) for services performed by an employee for his employer, including the cash value of all remuneration (including benefits) paid in any medium other than cash;" In addition to requiring that the remuneration must be for "services performed by an employee for his employer," the definition goes on to list 23 exclusions that must also be applied.[20]

See also

[edit]- Compensation of employees

- Employee benefit (non-monetary compensation in exchange for labor)

- Employment

- Labour economics

- List of countries by average wage

- Performance-related pay

- Wage labour

- Wage share

- Real wages

- List of sovereign states in Europe by net average wage

- Marginal factor cost

- Overtime

Political science:

References

[edit]- ^ Finley, Moses I. (1973). The ancient economy. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 65. ISBN 9780520024366.

- ^ Thompson, E. P. (1967). "Time, Work-Discipline, and Industrial Capitalism". Past and Present (38): 56–97. doi:10.1093/past/38.1.56. JSTOR 649749.

- ^ Dohrn-van Rossum, Gerhard (1996). History of the hour: Clocks and modern temporal orders. Thomas Dunlap (trans.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226155104.

- ^ Ezzamel, Mahmoud (July 2004). "Work Organization in the Middle Kingdom, Ancient Egypt". Organization. 11 (4): 497–537. doi:10.1177/1350508404044060. ISSN 1350-5084. S2CID 143251928.

- ^ a b Finley, Moses I. (1973). The ancient economy. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520024366.

- ^ Powell, Marvin A. (1995). "Metrology and Mathematics in Ancient Mesopotamia". In Sasson, Jack M. (ed.). Civilizations of the Ancient Near East. Vol. III. New York, NY: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 1955. ISBN 0-684-19279-9.

- ^ Hammurabi (1903). "Code of Hammurabi, King of Babylon". Records of the Past. 2 (3). Translated by Sommer, Otto. Washington, DC: Records of the Past Exploration Society: 85. Retrieved June 20, 2021.

234. If a shipbuilder builds ... as a present [compensation].

- ^ Hammurabi (1904). "Code of Hammurabi, King of Babylon" (PDF). Liberty Fund. Translated by Harper, Robert Francis (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 83. Retrieved June 20, 2021.

§234. If a boatman build ... silver as his wage.

- ^ a b Hammurabi (1910). "Code of Hammurabi, King of Babylon". Avalon Project. Translated by King, Leonard William. New Haven, CT: Yale Law School. Retrieved June 20, 2021.

- ^ Hammurabi (1903). "Code of Hammurabi, King of Babylon". Records of the Past. 2 (3). Translated by Sommer, Otto. Washington, DC: Records of the Past Exploration Society: 88. Retrieved June 20, 2021.

275. If anyone hires a ... day as rent therefor.

- ^ Hammurabi (1904). "Code of Hammurabi, King of Babylon" (PDF). Liberty Fund. Translated by Harper, Robert Francis (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 95. Retrieved June 20, 2021.

§275. If a man hire ... its hire per day.

- ^ "Student Login". Edgenuity. – Education 2020 Homeschool console, Vocabulary Assignment, definition entry for "wage rate" (may require login to view)

- ^ Magnusson, Charlotta. "Why Is There A Gender Wage Gap According To Occupational Prestige?." Acta Sociologica (Sage Publications, Ltd.) 53.2 (2010): 99-117. Academic Search Complete. Web. 26 Feb. 2015.

- ^ U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. "Earnings of Women and Men by Race and Ethnicity, 2007" Accessed June 29, 2012

- ^

Asli Demirgüç-Kunt, Michael Lokshin, Vladimir Kolchin (8 April 2023). "Effects of public sector wages on corruption: Wage inequality matters". Journal of Comparative Economics. 51 (3): 941–959. doi:10.1016/j.jce.2023.03.005. hdl:10986/35521.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Employees" as a category excludes all those who are self-employed, and this statistics only considers workers over the age of 16. U.S. Department of Labor. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2013-02-26), Characteristics of Minimum Wage Workers: 2012

- ^ Tennant, Michael. "Minimum Wage The Ups & Downs." New American (08856540) 30.12 (2014): 10-16. Academic Search Complete. Web. 26 Feb. 2015.

- ^ "Living Wage Calculator". livingwage.mit.edu. Retrieved 2023-10-02.

- ^ Aeppel, Timothy (August 29, 2022). "North American companies send in the robots, even as productivity slumps". Reuters.

- ^ USC 26 § 3401(a)

Further reading

[edit]- Galbraith, James Kenneth. Created Unequal: the Crisis in American Pay, in series, Twentieth Century Fund Book[s]. New York: Free Press, 1998. ISBN 0-684-84988-7

External links

[edit]- Lebergott, Stanley (2002). "Wages and Working Conditions". In David R. Henderson (ed.). Concise Encyclopedia of Economics (1st ed.). Library of Economics and Liberty. OCLC 317650570, 50016270, 163149563

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

- Wealth of Nations – click Chapter 8

- U.S. Department of Labor: Minimum Wage Laws – Different laws by State

- Average U.S. farm and non-farm wage

- Prices and Wages by Decade library guide – Prices and Wages research guide at the University of Missouri libraries