Vračar

Vračar

Врачар (Serbian) | |

|---|---|

Vračar plateau 2023 | |

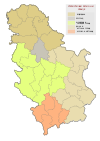

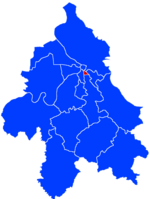

Location of Vračar within the city of Belgrade | |

| Coordinates: 44°47′43″N 20°28′04″E / 44.7953°N 20.4678°E | |

| Country | |

| City | |

| Status | Municipality |

| Settlements | 1 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Municipality of Belgrade |

| • Mun. president | Milan Nedeljković (SNS) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 2.87 km2 (1.11 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 142 m (466 ft) |

| Population (2022) | |

| • Total | 55,406 |

| • Density | 19,000/km2 (50,000/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 11000 |

| Area code | +381(0)11 |

| Car plates | BG |

| Website | www |

Vračar (Serbian Cyrillic: Врачар, pronounced [v̞rǎt͡ʃaːr]) is an affluent urban area and municipality of the city of Belgrade known as the location of many embassies and museums. According to the 2022 census results, the municipality has a population of 55,406 inhabitants.

With an area of only 287 hectares (710 acres), it is the smallest of all Belgrade's (and Serbian) municipalities, but also the most densely populated. Vračar is one of the three municipalities that constitute the very center area of Belgrade, together with Savski Venac and Stari Grad. It is an affluent municipality, having one of the most expensive real estate prices within Belgrade, and has the highest proportion of university educated inhabitants compared to all other Serbian municipalities.[2] One of the most famous landmarks in Belgrade, the Saint Sava Church is located in Vračar.

Vračar borders five other Belgrade municipalities: Voždovac to the south, Zvezdara to the east, Palilula to the northeast, Stari Grad to the north and Savski Venac to the west. It is generally bounded by the three boulevards: Boulevard of Liberation, Southern Boulevard and the Boulevard of King Aleksandar.

Though today the smallest municipality of Belgrade, historically Vračar occupied much larger territory. It was divided in three parts: East Vračar, which roughly occupies the modern municipality, West Vračar which is today a local community (sub-municipal unit) within the municipality of Savski Venac and Great Vračar, which is today known as Zvezdara, though the local community of Vračarsko Polje (Vračar Field) retained its name within the Zvezdara municipality.[3]

Geography

[edit]The neighborhood of Vračar is located on the top of the Vračar plateau, partially in the easternmost section of the municipality of Savski Venac as a result of a series of administrative changes of municipal boundaries after World War II. Despite its small area, being located less than a kilometer away from downtown (Terazije) it borders many other Belgrade neighborhoods: the square and neighborhood of Slavija to the north, Palilula to the northeast, Čubura and Gradić Pejton to the east, Neimar to the south and the park and neighborhood of Karađorđev Park to the southwest.

With 132 metres (433 feet), Vračar plateau is one of the highest points in downtown Belgrade, which is generally built on a hilly terrain (32 hills altogether).[4] The top of the hill was flattened and turned into the plateau when earth from the top was used to cover and drain the pond on Slavija, in the western foothills of the Vračar hill.[5] Almost no geographical features survive today as the area is completely urbanized, except for the small section of Karađorđev Park on the southern slopes of the plateau. Some much larger parks, like major portion of Karađorđev Park or parks Manjež and Tašmajdan are left just outside the Vračar's administrative borders.

Cityscape

[edit]

The most dominant feature of modern Vračar is the massive Church of Saint Sava. Its decades long, troubled construction shaped not only the present appearance of the plateau but also the entire skyline of Belgrade. The plateau has been reshaped in the early 2000s, with fountains, marble access roads to the church with pillars, and playgrounds added, while the already existing monument to the leader of the First Serbian Uprising, Karađorđe, was erected on a low, artificial hillock. The plateau is also the location of the National Library of Serbia and Karađorđev Park begins here, with the craftsmen settlement of Gradić Pejton and the bohemian quarter of Čubura nearby.

History

[edit]

Vračar (derived from Serbian word vrač meaning the 'medicine man', 'healer') was first mentioned in 1440, during the siege of Belgrade by the Ottoman sultan Murad II. Ottoman map from 1492 mentions Vračar as a tower.[3] In 1560 it is mentioned as the Christian village outside the fortress of Kalemegdan with 17 houses. It is believed this village is the place where in 1595 the Turkish grand vizier Sinan Pasha burned at the stake the remains of Saint Sava, a major Serbian saint, to pacify and punish a rebellious population.

19th century

[edit]At the beginning of the 19th century Vračar, as a geographical term, referred to a much wider area, from the village of Savamala (present Mostar) on the west to the village of Paliula (present neighborhood of Karaburma), which means it used to cover at least three times larger territory than the municipality covers today. By order of prince Miloš Obrenović, an alternative city centre with western characteristics was designed and built here while city of Belgrade was still under Turkish rule and for three quarters an oriental town with all the characteristics of Islamic architecture. On the other hand, Vračar was built with broad streets and boulevards, first parks and monuments. It was housing all Serbian public buildings and state institutions in Belgrade, known as a place where the remains of the Serbian Saint Archbishop Sava Nemanjic were burned by Turks. The Masonic Temple on this site was destroyed during the German bombing of Belgrade on 6 April 1941. Today, it is the site of the biggest Christian Orthodox Cathedral in the world.

The Times on 17 October 1843 published a text full of exultations. 'Four years have passed since the time when I was last here, and how Belgrade has changed! I have hardly recognised it. The high belfry on the church (Cathedral) now screens by its shadow the Turkish mosques; many shops are now provided with new doors and glass windows, oriental clothing is more rare and houses with several storeys, in European manner, are being built everywhere'.

Many architects-baumeisters (builders) Germans, Czechs, Italians and the Serbians who appeared only at the end of the 1860s built new Serbian Belgrade in Vračar. After 1867, when Turkish military garrisons left the Belgrade fortress Kalemegdan they extended their architectural activities on the ruins of the Turkish houses (Stambol gate, Dorćol, Palilula) and on the ruins of the Serbian huts in the Sava river port, Savamala.

When Belgrade was divided into six quarters in 1860, Vračar was one of them.[6] By the census of 1883 it had a population of 5,965.[7]

In the eastern section of Vračar, on the border of the Kalenić, Čubura and Krunski Venac neighborhoods, a settlement of one-floor villas began to develop in the early 1920s. At that time, a tram line No. 1-a was passing through here, connecting downtown to Crveni Krst. As majority of the parcels were purchased by the army generals and their family members, the neighborhood became known as the "Quarter of the Generals" (Milivoje Zečević, Bogoljub Ilić, Svetislav Milosavljević, families Kocić, Lukić, Petrović, Đonović, etc.). The villas were later upgraded with additional floors and were given names (Villa Stana, Villa Kocić, Villa Ilić).[8]

20th century

[edit]Since the 1880s, the neighborhood was roughly divided into Zapadni Vračar (West Vračar) and Istočni Vračar (East Vračar), divided by the road of Šumadijski put (present Boulevard of Liberation). The municipality of Vračar was officially formed in 1952 after Belgrade was administratively reorganized from districts (rejon) to municipalities. Already on 1 September 1955 Vračar was divided into Zapadni Vračar (West Vračar) and Istočni Vračar (East Vračar). Year and a half later, on 1 January 1957, parts of Istočni Vračar merged with the municipality of Neimar and the western part of the municipality of Terazije to create new, albeit the smallest municipality in Belgrade, Vračar. Zapadni Vračar became municipality of Savski Venac, while the easternmost section of Istočni Vračar became part of the municipality of Zvezdara (local community of Vračarsko Polje; Zvezdara hill itself was styled Veliki Vračar - Big Vračar).

New municipal healthcare center, HC Vračar, was built from 1969 to 1972.[9]

21st century

[edit]In the 21st century, a massive construction in Vračar began, with old houses and villas being demolished to make way for the high-rise buildings. The period of corruption and "investors' urbanism" ensued, where structures were built by the wishes of the investors, disregarding laws and regulations. As a result, accidents happened, most notably in the autumn of 2008 and in July 2021. In 2008 in the Dubljanska Street, while the foundations were dug for a new building, four neighboring houses were undermined and collapsed, with residents never getting legal satisfaction. In 2021, due to the same action, a ground floor of the older building in the Vidovdanska Street caved in. With non-planned construction of new buildings, and added annexes onto the existing ones, structures built without space between them where residents almost "sleep on top of each other", the overcrowded neighborhood earned a moniker of Favela Vračar. The difference with the Brazilian favelas, which are home to the poorest classes of society, is that apartments in Vračar's favela are purchased by the affluent class, who find it a matter of prestige to live in Vračar.[10][11][12][13][14]

Proclamation of several protected areas in Vračar, including some preliminary and some announced, did not prevent demolition of old houses, including some deemed historically and artistically valuable. In some cases, when the protection would be announced, the investors would hasten the demolitions and construction. Various other scandals received public and media attention, like planned demolition of villas in the neighborhood of Neimar, addition of new floors on the old buildings in the Krunska Street, demolition of several Interbellum villas in the neighborhood of Krunski Venac, especially the 1927 villa in Takovska Street as one of the first representatives of the moderna-style in Belgrade, which was demolished in 2018. The House of Pera Velimirović at 25 Resavska Street, built in 1908, was demolished in June 2020, despite being under the preliminary protection. In December, after public protest subdued, even older house from the 19th century, on the lot adjoined to the already demolished building, was demolished, too.[15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23] Other projects which caused public debate include attempt of building on the small green area in the Tomaša Ježa, which prompted residents to self-organize and clash with the investors since 2017, and house at 4 Sredačka Street. Designed by then official city urbanist Milutin Folić, and built by his family studio (he officially withdrew after taking the office), the building was not permitted until he took office. The terraces of the building spread above the neighboring, urbanized lot, but when residents complained, city replied that this area was meant to be the square anyway.[24]

In September 2020, city administration made public its plan for demolishing the entire block bounded by the Krunska, Smiljanićeva, Kneginje Zorke and Njegoševa streets, including the building of the Museum of Natural History. After major negative public, experts' and political reaction, only few days later city administration abandoned the plans, and in April 2021 placed this specific block under protection, calling it a "priceless heritage".[25][26][27] City announced new rules in 2020, which stipulated that the facades of the new buildings which are not in the protected zones will have to be approved by the Institute for the Cultural Monuments Protection, but nothing changed. When on 25 December 2020 temporary protection of another zone, East Vračar, expired, the demolitions expedited and the "edifices started to fall down like houses of cards". It included the villa at 4 Nikolaja Krasnova Street, with a recognizable facade, which caused further public objections. Institute stated that it works on the house's protection and that it will protect it in 2022, but it was nevertheless demolished in August 2021.[28] Instead of a one-floor villa, a 7-storey building will be built, though the façade should resemble the old villa.[29]

The smallest municipality in Serbia, in terms of area, became the example of urban chaos. As there are basically no non-urbanized lots left, the demolition of old villas and houses sped up. Other, public areas were also destroyed to make room for highrise, so some sections have no sidewalk at all, and the green areas were reduced.[24] Streets turned into "tunnels" and there is no chance of finding free parking spot anymore. It was also noted that investors usually began demolitions in summer, when people tend to be on vacation, so that reduced number of residents and neighbors can protest.[28] Belgrade school shooting occurred in Vračar on 3 May 2023.[30]

Neighborhoods

[edit]As Vračar has a very small area by itself, its sub-neighborhoods are also small, some of them encompassing only a street or so:

|

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1948 | 62,158 | — |

| 1953 | 75,139 | +3.87% |

| 1961 | 88,422 | +2.06% |

| 1971 | 84,291 | −0.48% |

| 1981 | 78,862 | −0.66% |

| 1991 | 69,680 | −1.23% |

| 2002 | 58,386 | −1.59% |

| 2011 | 56,333 | −0.40% |

| 2022 | 55,406 | −0.15% |

| Source: [31] | ||

As the other two central Belgrade municipalities, Stari Grad and Savski Venac, Vračar has been depopulating for the last five decades. Despite that, Vračar is by far, thanks to its small area, the most densely populated municipality of Belgrade, with 18,967 inhabitants per square kilometer (2011 census; 28,380 back in 1971).

Ethnic structure

[edit]The ethnic composition of the municipality:[32]

| Ethnic group | Population |

|---|---|

| Serbs | 45,331 |

| Yugoslavs | 859 |

| Russians | 476 |

| Montenegrins | 370 |

| Croats | 150 |

| Macedonians | 117 |

| Romani | 108 |

| Gorani | 90 |

| Slovenes | 74 |

| Muslims | 46 |

| Bosniaks | 45 |

| Others | 686 |

| Undeclared/Unknown | 7,054 |

| Total | 55,406 |

Administration

[edit]Recent presidents of the municipality:

- 1993–1996: Dragan Maršićanin (b. 1950)

- 1996–2006: Milena Milošević (1950–2016)

- 2006–2015: Branimir Kuzmanović (b. 1968)

- 2015–2016: Tijana Blagojević (b. 1980)

- 2016–present: Milan Nedeljković (b. 1957)

- 2024-present: Uljan Uljanijević (b. 2005)

Mrs Dunja Vlahović (b. 1912), who was municipal president from January 1957 when Vračar was restored as one municipality, was one of the first female municipal presidents in Serbia.

District (Serbian: srez) which comprised the suburban area of Belgrade after 1945 was called Vračar District (Vračarski srez) though the name Belgrade District was also used. In 1955 the Vračar District merged with the City of Belgrade and parts of some bordering districts to create new, enlarged Belgrade District.

Economy

[edit]The following table gives a preview of total number of registered people employed in legal entities per their core activity (as of 2018):[33]

| Activity | Total |

|---|---|

| Agriculture, forestry and fishing | 109 |

| Mining and quarrying | 53 |

| Manufacturing | 1,840 |

| Electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply | 1,084 |

| Water supply; sewerage, waste management and remediation activities | 416 |

| Construction | 2,027 |

| Wholesale and retail trade, repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles | 5,747 |

| Transportation and storage | 1,191 |

| Accommodation and food services | 2,320 |

| Information and communication | 2,099 |

| Financial and insurance activities | 1,031 |

| Real estate activities | 351 |

| Professional, scientific and technical activities | 4,608 |

| Administrative and support service activities | 5,510 |

| Public administration and defense; compulsory social security | 2,338 |

| Education | 1,678 |

| Human health and social work activities | 2,413 |

| Arts, entertainment and recreation | 1,373 |

| Other service activities | 1,979 |

| Individual agricultural workers | 8 |

| Total | 38,175 |

Characteristics

[edit]

Vračar is a residential and very important commercial part of Belgrade. The tall skyscraper in downtown Belgrade, the Beograđanka, Cvetni Trg (famous for its flower shops), Treća beogradska gimnazija (Third Belgrade High School-Elite high school in Belgrade) and the square of Slavija occupy the western section of the municipality. Other important features are the Church of Saint Sava and the National Library of Serbia on the Vračar plateau, northern section of the big interchange Autokomanda and the stadium of the FK Obilić (Miloš Obilić Stadium) and the Architecture high school in the extreme west of the municipality. Commercial center of the municipality is the area surrounding the Kalenić, largest open green market in Belgrade.

The "Vračar plane tree" is a tree in the Makenzijeva street, protected as the natural monument. It is a London plane, 23 m (75 ft) high in 2013 and is estimated to be planted c. 1860.[34]

International cooperation

[edit]Vračar is twinned with following cities and municipalities:[35]

See also

[edit]- Istočni Vračar

- Zapadni Vračar

- Veliki Vračar

- Subdivisions of Belgrade

- List of Belgrade neighborhoods and suburbs

Historical references

[edit]- Beograd - Izdanje opštine beogradske, 1911;

- Zapisi starog Beograđanina 2000;

- Iz starog Beograda, Živorad P. Jovanović 1964;

- Siluete starog Beograda, Milan Jovanović - Stojimirović, 1971;

- Uspon Beograda, Milivoje M.Kostić, 2000;

- Beogradske gradske pijace, JKP Beogradske pijace, 1999;

- Vračarski glasnik, 1997–2004

References

[edit]- ^ "Насеља општине Врачар" (PDF). stat.gov.rs (in Serbian). Statistical Office of Serbia. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- ^ "Srbija: Svaki deseti građanin visoko obrazovan". www.vesti.rs. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- ^ a b Marija Brakočević (21 May 2014). "Beograd leži na 23 brda" [Belgrade lies on 23 hills]. Politika (in Serbian).

- ^ "Opservatorija: Beograd - Vračar (osnovana 1887 godine)" (in Serbian). Politika. 2017.

- ^ Milan Četnik, "Generali na koti Vračar", Politika (in Serbian)

- ^ Dejan Aleksić (9 May 2017), "Šest decenija opštine Palilula - Nekad selo, a danas urbana celina grada", Politika (in Serbian)

- ^ Belgrade by the 1883 census

- ^ Nenad Novak Stefanović (9 November 2018). "Кад је трамвај звонио Врачаром" [When tram was ringing through Vračar]. Politika-Moja kuća (in Serbian). p. 01.

- ^ Branka Jakšić (27 April 1972). Отворен нови дом здравља на Врачару [New healthcare center opened in Vračar]. Politika (reprint on 27 April 2022) (in Serbian).

- ^ Mina Ćurčoć, Dejan Aleksić (17 July 2021). Срушило се приземље зграде у Видовданској улици на Врачару [Ground floor of a building in Vidovdanska Street collapsed]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 14.

- ^ Dejan Aleksić, Branka Vasiljević (17 July 2021). Досадашња урушавања зграда: У Дубљанској, Новоградској и у Доситејевој у Новом Саду [Previous collapses of buildings: In Dubljanska, Novogradska and Dositejeva (in Novi Sad) streets]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 14.

- ^ Milan Janković (17 July 2021). Врачарска фавела [Favela Vračar]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 14.

- ^ Marko M. Dragoslavić [@DragoslavicM] (16 July 2021). "trenutak kada se srusila zgrada u Vidovdanskoj ulici na Vracaru" [The moment building in Vračar's Vidovdanska Street collapsed] (Tweet) (in Serbian) – via Twitter.

- ^ Tanja Jordović [@tanjajorda] (16 July 2021). "Beograd, opština Vračar 2027. godina" [Belgrade, Vračar municipality, year 2027. (humorous montage)] (Tweet) (in Serbian) – via Twitter.

- ^ Dejan Aleksić, Branka Vasiljević (25 July 2021). Куће тону и нестају, решења нема на видику [Houses sink and disappear, solution not in sight]. Politika (in Serbian).

- ^ N1, FoNet (12 September 2018). "Počelo rušenje vile iz 1927. godine u Topolskoj" [Demolition of the 1927 villa in Topolska began] (in Serbian). N1.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Milica Rilak (16 June 2020). "Počelo rušenje kuće u Resavskoj: Kome treba kulturno nasleđe" [Demolition of house in Resavska began: who needs cultural heritage anyway] (in Serbian). Nova S.

- ^ Milena Ilić Mirković (19 June 2020). "Nastavljeno rušenje u Resavskoj: "Nestaje istorija Beograda"" [Demolition in Resavska continued: "Belgrade's history disappearing"] (in Serbian). Nova S.

- ^ Milan Janković (22 June 2020). Један од пет - Рушење културе [1 to 5 - Demolition of culture]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 14.

- ^ N1 (28 December 2020). "N1: U centru Beograda srušena kuća iz 19. veka, investitor tvrdi da ima dozvolu" [N1: 19th century house in downtown Belgrade demolished, investor claims he obtained all permits] (in Serbian). Nova Srpska Politička Misao.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Daliborka Mučibabić (22 May 2021). Крунски венац и Светосавски плато - културна добра [Krunski Venac and Santi Sava Plateau - cultural monuments]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 14.

- ^ Daliborka Mučibabić (28 April 2021). Зауставити рушење виле [Demolition of the villa should be stopped]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 16.

- ^ Mina Ćurčić (14 May 2021). Неизвесна судбина виле у амбијенталној целини "Котеж Неинар" [Dubious faith of the villa in spatial unit "Kotež Neimar"]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 19.

- ^ a b Dušan Mlađenović (15 May 2021). "Urbanistički haos na Vračaru: Višespratnice umesto vila, zelenila sve manje…" [Urban chaos in Vračar: highrise instead of villa's greenery reduced] (in Serbian). N1.

- ^ Заустављени урбанистички планови на Врачару [Urban plans for Vračar abandoned]. Politika (in Serbian). 28 September 2020. p. 14.

- ^ N1 Beograd (28 September 2020). "Arhitekta o planu za rušenje zgrada na Vračaru: Nešto tu "debelo" nije u redu" [Architect on demolition plan for Vračar: Something is deeply wrong about it]. N1 (in Serbian).

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Daliborka Mučibabić (14 April 2021). "Kuće u Smiljanićevoj ulici pod zaštitom" [Houses in Smiljanićeva Street under protection]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 19.

- ^ a b Daliborka Mučibabić (16 August 2021). "Zaštita istekla, kuće padaju kao kule od karata" [Protection expired, houses fall like houses of cards]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 14.

- ^ Daliborka Mučibabić (10 May 2022). "Na mestu porodične kuće na Vračaru – sedmospratnica" [Seven-storey building on location of a familz house in Vračar]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 17.

- ^ "Zvanične informacije: Ubijeno osam učenika i čuvar - Pucnjava u Osnovnoj školi Vladislav Ribnikar - Nedeljnik Vreme". Vreme (in Serbian). 3 May 2023. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ "2011 Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in the Republic of Serbia" (PDF). stat.gov.rs. Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ ETHNICITY - Data by municipalities and cities (PDF). Belgrade, Serbia: Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. 2023. pp. 32–33. ISBN 9788661612282. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 November 2023. Retrieved 22 November 2023.

- ^ "Municipalities and Regions of the Republic of Serbia, 2019" (PDF). stat.gov.rs. Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. 25 December 2019. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- ^ Vladimir Vukasović (9 June 2013), "Prestonica dobija još devet prirodnih dobara", Politika (in Serbian)

- ^ [1] Archived 21 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine Stalna konferencija gradova i opština. Retrieved on 18 June 2007.