Vladimir Mayakovsky

Vladimir Mayakovsky | |

|---|---|

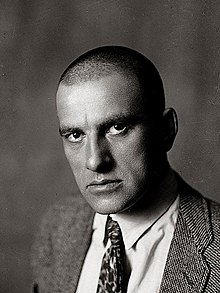

Mayakovsky in 1920 | |

| Native name | Владимир Маяковский |

| Born | Vladimir Vladimirovich Mayakovsky 19 July [O.S. 7 July] 1893 Baghdati, Kutais Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | 14 April 1930 (aged 36) Moscow, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Alma mater | Stroganov Moscow State University of Arts and Industry, Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture |

| Genre | Poetry |

| Subject | New Soviet man |

| Literary movement | |

| Years active | 1912–1930 |

| Signature | |

| |

Vladimir Vladimirovich Mayakovsky (Russian: Владимир Владимирович Маяковский, IPA: [məjɪˈkofskʲɪj] ; 19 July [O.S. 7 July] 1893 – 14 April 1930) was a Russian poet, playwright, artist, and actor. During his early, pre-Revolution period leading into 1917, Mayakovsky became renowned as a prominent figure of the Russian Futurist movement. He co-signed the Futurist manifesto, A Slap in the Face of Public Taste (1913), and wrote such poems as "A Cloud in Trousers" (1915) and "Backbone Flute" (1916). Mayakovsky produced a large and diverse body of work during the course of his career: he wrote poems, wrote and directed plays, appeared in films, edited the art journal LEF, and produced agitprop posters in support of the Communist Party during the Russian Civil War of 1917–1922.

Though Mayakovsky's work regularly demonstrated ideological and patriotic support for the ideology of the Bolsheviks and a strong admiration of Vladimir Lenin,[1][2] his relationship with the Soviet state was always complex and often tumultuous. Mayakovsky often found himself engaged in confrontation with the increasing involvement of the Soviet state in cultural censorship and the development of the State doctrine of Socialist realism. Works that criticized or satirized aspects of the Soviet system, such as the poem "Talking With the Taxman About Poetry" (1926), and the plays The Bedbug (1929) and The Bathhouse (1929), met with scorn from the Soviet state and literary establishment.

In 1930, Mayakovsky committed suicide. Even after death, his relationship with the Soviet state remained unsteady. Though Mayakovsky had previously been harshly criticized by Soviet governmental bodies such as the Russian Association of Proletarian Writers, Premier Joseph Stalin described Mayakovsky after his death as "the best and the most talented poet of our Soviet epoch".[3]

Life and career

[edit]

Vladimir Vladimirovich Mayakovsky was born in 1893 in Baghdati, Kutais Governorate, Georgia, then part of the Russian Empire, to Alexandra Alexeyevna (née Pavlenko), a housewife, and Vladimir Mayakovsky, a local forester. His father belonged to a noble family and was a distant relative of the writer Grigory Danilevsky. Vladimir Vladimirovich had two sisters, Olga and Lyudmila, and a brother Konstantin, who died at the age of three.[4] The family was of Russian and Zaporozhian Cossack descent on their father's side and Ukrainian on their mother's.[5]

At home the family spoke Russian. With his friends and at school, Mayakovsky spoke Georgian. "I was born in the Caucasus, my father is a Cossack, my mother is Ukrainian. My mother tongue is Georgian. Thus three cultures are united in me," he told the Prague newspaper Prager Presse in a 1927 interview.[6] For Mayakovsky, Georgia was his eternal symbol of beauty. "I know, it's nonsense, Eden and Paradise, but since people sang about them // It must have been Georgia, the joyful land, that those poets were having in mind", he wrote later.[4][7]

In 1902, Mayakovsky joined the Kutaisi gymnasium. Later as a 14-year-old, he took part in socialist demonstrations in the town of Kutaisi.[4] His mother, aware of his activities, apparently did not mind. "People around warned us we were giving a young boy too much freedom. But I saw him developing according to the new trends, sympathized with him and pandered to his aspirations," she later remembered.[5] His father died suddenly in 1906, when Mayakovsky was thirteen. (The father pricked his finger on a rusty pin while filing papers and died of blood poisoning.) His widowed mother moved the family to Moscow after selling all their movable property.[4][8]

In July 1906, Mayakovsky joined the 4th form of Moscow's 5th Classic gymnasium and soon developed a passion for Marxist literature. "Never cared for fiction. For me it was philosophy, Hegel, natural sciences, but first and foremost, Marxism. There'd be no higher art for me than "The Foreword" by Marx," he recalled in the 1920s in his autobiography I, Myself.[9] In 1907 Mayakovsky became a member of his gymnasium's underground Social Democrats' circle, taking part in numerous activities of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party which he, given the nickname "Comrade Konstantin",[10] joined the same year.[11][12] In 1908, the boy was dismissed from the gymnasium because his mother was no longer able to afford the tuition fees.[13] For two years he studied at the Stroganov School of Industrial Arts, where his sister Lyudmila had started her studies a few years earlier.[8]

As a young Bolshevik activist, Mayakovsky distributed propaganda leaflets, possessed a pistol without a license, and in 1909 got involved in smuggling female political activists out of prison. This resulted in a series of arrests and finally an 11-month imprisonment.[10] It was in solitary confinement in the Moscow Butyrka prison that Mayakovsky started writing verses for the first time.[14] "Revolution and poetry got entangled in my head and became one," he wrote in I, Myself.[4] As a minor, Mayakovsky was spared a serious prison sentence (with associated deportation) and in January 1910 was released.[13] A warden confiscated the young man's notebook. Years later Mayakovsky conceded that was all for the better, yet he always cited 1909 as the year his literary career started.[4]

Upon his release from prison, Mayakovsky remained an ardent Socialist, but realized his own inadequacy as a serious revolutionary. Having left the Party (never to re-join it), he concentrated on education. "I stopped my Party activities. Sat down and started to learn… Now my intention was to make the Socialist art," he later remembered.[15]

In 1911, Mayakovsky enrolled in the Moscow Art School. In September 1911 a brief encounter with fellow student David Burlyuk (which nearly ended with a fight) led to a lasting friendship and had historic consequences for the nascent Russian Futurist movement.[11][14] Mayakovsky became an active member (and soon a spokesman) for the group Hylaea (Гилея), which sought to free the arts from academic traditions: its members would read poetry on street corners, throw tea at their audiences, and make their public appearances an annoyance for the art establishment.[8]

Burlyuk, on having heard Mayakovsky's verses, declared him "a genius poet".[13][16] Later Soviet researchers tried to downplay the significance of the fact, but even after their friendship ended and their ways parted, Mayakovsky continued to give credit to his mentor, referring to him as "my wonderful friend". "It was Burlyuk who turned me into a poet. He read the French and the Germans to me. He pressed books on me. He would come and talk endlessly. He didn't let me get away. He would subsidize me with 50 kopeks each day so that I'd write and not be hungry," Mayakovsky wrote in "I, Myself".[10]

Literary career

[edit]

On 17 November 1912, Mayakovsky made his first public performance at Stray Dog, the artistic basement in Saint Petersburg.[11] In December of that year his first published poems, "Night" (Ночь) and "Morning" (Утро) appeared in the Futurists' Manifesto A Slap in the Face of Public Taste,[17] signed by Mayakovsky, as well as Velemir Khlebnikov, David Burlyuk and Alexey Kruchenykh, calling among other things for... "throwing Pushkin, Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, etc, etc, off the steamboat of the modernity."[11][13]

In October 1913, Mayakovsky gave the performance at the Pink Lantern café, reciting his new poem "Take That!" (Нате!) for the first time. The concert at the Petersburg's Luna-Park saw the premiere of the poetic monodrama Vladimir Mayakovsky, with the author in a leading role, stage decorations designed by Pavel Filonov and Iosif Shkolnik.[11][14] In 1913 Mayakovsky's first poetry collection called I (Я) came out, its original limited edition 300 copies lithographically printed. This four-poem cycle, handwritten and illustrated by Vasily Tchekrygin and Leo Shektel, later formed Part One of the 1916 compilation Simple as Mooing.[13]

In December 1913, Mayakovsky along with his fellow Futurist group members embarked on the Russian tour, which took them to 17 cities, including Simferopol, Sevastopol, Kerch, Odessa and Kishinev.[4] It was a riotous affair. The audiences would go wild and often the police stopped the readings. The poets dressed outlandishly, and Mayakovsky, "a regular scandal-maker" in his own words, used to appear on stage in a self-made yellow shirt which became the token of his early stage persona.[10] The tour ended on 13 April 1914 in Kaluga[11] and cost Mayakovsky and Burlyuk their education: both were expelled from the Art school, their public appearances deemed incompatible with the school's academic principles.[11][13] They learned of it while in Poltava from the local police chief, who chose the occasion as a pretext to ban the Futurists from performing on stage.[5]

Having won 65 rubles in a lottery, in May 1914, Mayakovsky went to Kuokkala, near Petrograd. Here he put the finishing touches to A Cloud in Trousers, frequented Korney Chukovsky's dacha, sat for Ilya Repin's painting sessions and met Maxim Gorky for the first time.[18] As World War I began, Mayakovsky volunteered but was rejected as 'politically unreliable'. He worked for the Lubok Today company which produced patriotic lubok pictures, and in the Nov (Virgin Land) newspaper, which published several of his anti-war poems ("Mother and an Evening Killed by the Germans", "The War is Declared", "Me and Napoleon" among others).[5] In the summer of 1915 Mayakovsky moved to Petrograd where he started contributing to the New Satyrikon magazine, writing mostly humorous verse in the vein of Sasha Tchorny, one of the journal's former stalwarts. Subsequently, Maxim Gorky invited the poet to work for his journal, Letopis.[4][15]

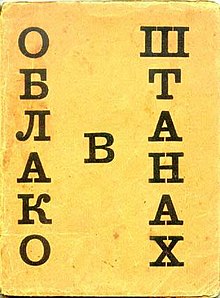

In June of that year, Mayakovsky fell in love with a married woman, Lilya Brik, who eagerly took upon herself the role of a 'muse'. Her husband Osip Brik seemed not to mind and became the poet's close friend; later he published several books by Mayakovsky and used his entrepreneurial talents to support the Futurist movement. This love affair, as well as his ideas on World War I and Socialism, strongly influenced Mayakovsky's best known works: A Cloud in Trousers (1915),[19] his first major poem of appreciable length, followed by Backbone Flute (1915), The War and the World (1916) and The Man (1918).[11]

When his mobilization form finally arrived in the autumn of 1915, Mayakovsky found himself unwilling to go to the frontlines. Assisted by Gorky, he joined the Petrograd Military Driving school as a draftsman and was studying there until early 1917.[11] In 1916 Parus (The Sail) Publishers (again led by Gorky), published Mayakovsky's poetry compilation called Simple As Mooing.[4][11]

1917–1927

[edit]

Mayakovsky embraced the Bolshevik Russian Revolution wholeheartedly and for a while even worked in Smolny, Petrograd, where he saw Vladimir Lenin.[11] "To accept or not to accept, there was no such question… [That was] my Revolution," he wrote in I, Myself autobiography.[citation needed] In November 1917 he took part in the Communist Party's Central committee-sanctioned assembly of writers, painters and theatre directors who expressed their allegiance to the new political regime.[11] In December that year "The Left March" (Левый марш, 1918) premiered at the Navy Theater, with sailors as an audience.[15]

In 1918, Mayakovsky started the short-lived Futurist Paper. He also starred in three silent films made at the Neptun Studios in Petrograd he had written scripts for. The only surviving one, The Lady and the Hooligan, was based on the La maestrina degli operai (The Workers' Young Schoolmistress) published in 1895 by Edmondo De Amicis, and directed by Evgeny Slavinsky. The other two, Born Not for the Money and Shackled by Film were directed by Nikandr Turkin and are presumed lost.[11][20]

On 7 November 1918, Mayakovsky's play Mystery-Bouffe premiered at the Petrograd Musical Drama Theatre.[11] Representing a universal flood and the subsequent joyful triumph of the "Unclean" (the proletariat) over the "Clean" (the bourgeoisie), this satirical drama's re-worked, 1921 version enjoyed even greater popular acclaim.[14][15] However, the author's attempt to make a film of the play failed, its language deemed "incomprehensible for the masses."[8]

In December 1918, Mayakovsky was involved with Osip Brik in discussions with the Viborg district party school of the Russian Communist Party (bolsheviks) (RKP(b)) to set up a Futurist organisation affiliated to the party. Named Komfut, the organisation was formally founded in January 1919, but was swiftly dissolved following the intervention of Anatoly Lunacharsky.[21]

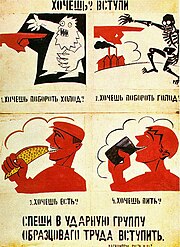

In March 1919, Mayakovsky moved back to Moscow where Vladimir Mayakovsky's Collected Works 1909–1919 was released. The same month he started working for the Russian State Telegraph Agency (ROSTA) creating—both graphic and text— satirical Agitprop posters, aimed mostly at informing the country's largely illiterate population of the current events.[11] In the cultural climate of the early Soviet Union, his popularity grew rapidly, even if among the members of the first Bolshevik government, only Anatoly Lunacharsky supported him; others treated the Futurist art more skeptically. Mayakovsky's 1921 poem, 150 000 000 failed to impress Lenin, who apparently saw in it little more than a formal futuristic experiment. More favourably received by the Soviet leader was his next one, "Re Conferences" which came out in April.[11]

A vigorous spokesman for the Communist Party, Mayakovsky expressed himself in many ways. Contributing simultaneously to numerous Soviet newspapers, he poured out topical propagandistic verses and wrote didactic booklets for children while lecturing and reciting all over Russia.[14]

In May 1922, after a performance at the House of Publishing at the charity auction collecting money for the victims of Povolzhye famine, he went abroad for the first time, visiting Riga, Berlin and Paris, where he was invited to the studios of Fernand Léger and Picasso.[8] Several books, including The West and Paris cycles (1922–1925) were created as a result.[11]

From 1922 to 1928, Mayakovsky was a prominent member of the Left Art Front (LEF) he helped to found (and coin its "literature of fact, not fiction" credo) and for a while defined his work as Communist Futurism (комфут).[13] He edited, along with Sergei Tretyakov and Osip Brik, the journal LEF, its stated objective being "re-examining the ideology and practices of the so-called leftist art, rejecting individualism and increasing Art's value for the developing Communism."[12] The journal's first, March 1923, issue featured Mayakovsky's poem About That (Про это).[11] Regarded as a LEF manifesto, it soon came out as a book illustrated by Alexander Rodchenko who also used some photographs made by Mayakovsky and Lilya Brik.[22]

In May 1923, Mayakovsky spoke at a massive protest rally in Moscow, in the wake of Vatslav Vorovsky's assassination. In October 1924 he gave numerous public readings of the 3,000-line epic Vladimir Ilyich Lenin written on the death of the Soviet Communist leader. Next February it came out as a book, published by Gosizdat. Five years later Mayakovsky's rendition of the third part of the poem, at the Lenin Memorial evening in the Bolshoi Theatre ended with 20-minutes ovation.[14][23] In May 1925 Mayakovsky's second trip took him to several European cities, then to the United States, Mexico[24] and Cuba. In the US, he visited New York, Cleveland, Detroit, Chicago, Pittsburgh, and Philadelphia, and planned a trip to Boston that was never realized.[25] His book of essays My Discovery of America came out later that year.[11][13]

In January 1927, the first issue of the New LEF magazine came out, again under Mayakovsky's supervision, now focusing on the documentary art. In all, 24 issues of it came out.[16] In October 1927 Mayakovsky recited his new poem All Right! (Хорошо!) for the audience of the Moscow Party conference activists in the Moscow's Red Hall.[11] In November 1927 a play called The 25th (and based upon the All Right! poem) premiered at the Leningrad Maly Opera Theatre. In summer 1928, disillusioned with LEF, he left both the organization and its magazine.[11]

1929–1930

[edit]

In 1929, the publishing house Goslitizdat released The Works by V. V. Mayakovsky in 4 volumes. In September 1929 the first assembly of the newly formed REF group gathered with Mayakovsky in the chair.[11] But behind this façade the poet's relationship with the Soviet literary establishment was quickly deteriorating. Both the REF-organized exhibition of Mayakovsky's work, celebrating the 20th anniversary of his literary career and the parallel event in the Writers' Club, "20 Years of Work" in February 1930, were ignored by the RAPP members and, more importantly, the Party leadership, particularly Stalin whose attendance he was greatly anticipating. It was becoming evident that such experimental art was no longer welcomed by the regime, and that the country's most famous poet was increasingly losing favor with the higher echelons of the Party.[5]

Two of Mayakovsky's satirical plays, written specifically for Meyerkhold Theatre, The Bedbug (1929) and (in particular) The Bathhouse (1930) evoked stormy criticism from the Russian Association of Proletarian Writers.[12] In February 1930 Mayakovsky joined RAPP, but in Pravda on 9 March, a leading member of RAPP, Vladimir Yermilov, writing "with all the authority of a 23 year old who had not seen the play but had read part of the script"[26] categorised Mayakovsky as one of the 'petit bourgeois revolutionary intelligentsia', adding that "we hear a false 'leftist' note in Mayakovsky, a note which we know not only from literature....".[27] This was a potentially deadly political accusation, in that it implied an intellectual link between Mayakovsky and the Left Opposition, led by Leon Trotsky, whose supporters were in exile or prison. (Trotsky was known to admire Mayakovsky's poetry).[28] Mayakovsky retaliated by creating a huge poster mocking Yermilov, but was ordered by RAPP to take it down. In his suicide note Mayakovsky wrote "Tell Yermilov we should have completed the argument."[29]

The smear campaign continued in the Soviet press, sporting slogans like "Down with Mayakovshchina!" On 9 April 1930 Mayakovsky, reading his new poem "At the Top of My Voice", was shouted down by the student audience, for being 'too obscure'.[4][30]

Death

[edit]On 12 April 1930, Mayakovsky was seen in public for the last time: he took part in a discussion at the Sovnarkom meeting concerning the proposed copyright law.[11] On 14 April 1930, his current partner, actress Veronika Polonskaya, upon leaving his flat, heard a shot behind the closed door. She rushed in and found the poet lying on the floor; he had apparently shot himself through the heart.[11][31] The handwritten death note read: "To all of you. I die, but don't blame anyone for it, and please do not gossip. The deceased disliked that sort of thing terribly. Mother, sisters, comrades, forgive me – this is not a good method (I do not recommend it to others), but there is no other way out for me. Lily – love me. Comrade Government, my family consists of Lily Brik, mama, my sisters, and Veronika Vitoldovna Polonskaya. If you can provide a decent life for them, thank you. Give the poem I started to the Briks. They'll sort them out."[citation needed] The 'unfinished poem' in his suicide note read, in part: "And so they say – "the incident dissolved" / the love boat smashed up / on the dreary routine. / I'm through with life / and [we] should absolve / from mutual hurts, afflictions and spleen."[32] Mayakovsky's funeral on 17 April 1930, was attended by around 150,000, the third largest event of public mourning in Soviet history, surpassed only by those of Vladimir Lenin and Joseph Stalin.[3][33] He was interred at the Moscow Novodevichy Cemetery.[12]

Controversy surrounding death

[edit]

Mayakovsky's suicide occurred after a dispute with Polonskaya, with whom he had a brief but unstable romance. Polonskaya, who was in love with the poet, but unwilling to leave her husband, was the last one to see Mayakovsky alive.[citation needed] But, as Lilya Brik stated in her memoirs, "the idea of suicide was like a chronic disease inside him, and like any chronic disease it worsened under circumstances that, for him, were undesirable…"[10] According to Polonskaya, Mayakovsky mentioned suicide on 13 April, when the two were at Valentin Katayev's place, but she thought he was trying to emotionally blackmail her and "refused to believe for a second [he] could do such a thing."[31]

The circumstances of Mayakovsky's death became a matter of lasting controversy. It appeared that the suicide note had been written two days before his death. Soon after the poet's death, Lilya and Osip Brik were hastily sent abroad. The bullet removed from his body didn't match the model of his pistol, and his neighbors were later reported to say they'd heard two shots.[10] Ten days later, the officer investigating the poet's suicide was himself killed, fueling speculation about the nature of Mayakovsky's death.[12] Such speculation, often alluding to suspicion of murder by State services, especially intensified during the periods of first Krushchevian de-Stalinisation, later Glasnost, and Perestroika, as Soviet politicians sought to weaken Stalin's reputation (or Brik's, and by association, Stalin's)[citation needed] and the positions of contemporary opponents. According to Chantal Sundaram:

The extent to which rumours of Mayakovsky's murder remained widespread is indicated by the fact that even as late as the end of 1991 they prompted the State Mayakovsky Museum to commission an expert medical and criminological inquiry into the material evidence of his death kept in the museum: photographs, the shirt with traces from the gunshot, the carpet on which Mayakovsky fell, and the authenticity of the suicide note. The possibility of a forgery, suggested by [Andrei] Koloskov, had survived as a theory with different variants. But the results of a detailed hand-writing analysis found that the suicide note was undoubtedly written by Mayakovsky, and also included the conclusion that its irregularities "depict a diagnostic complex, testifying to the influence… at the moment of execution… of 'disconcerting' factors, among which the most probable is a psycho-physiological state linked with agitation." Although the findings are hardly surprising, the event is indicative of a fascination with Mayakovsky's contradictory relationship with the Soviet authorities which survived into the era of perestroika, despite the fact that he was being attacked and rejected for his political conformism at this time.[3]

Private life

[edit]Mayakovsky met husband and wife Osip and Lilya Brik in July 1915 at their dacha in Malakhovka nearby Moscow. Soon after that Lilya's sister, Elsa Triolet, who'd had a brief affair with the poet before, invited him to the Briks' Petrograd flat. The couple at the time showed no interest in literature and were successful coral traders.[34] That evening Mayakovsky recited the yet unpublished poem A Cloud in Trousers and announced it as dedicated to the hostess ("For you, Lilya"). "That was the happiest day in my life", was how he referred to the episode in his autobiography years later.[4] According to Lilya Brik's memoirs, her husband too fell in love with the poet ("How could I have possibly failed to fall for him, if Osya loved him so?" – she once argued),[35] whereas "Volodya did not merely fall in love with me; he attacked me, it was an assault. For two and a half years I didn't have a moment's peace. I understood right away that Volodya was a genius, but I didn't like him. I didn't like clamorous people ... I didn't like the fact that he was so tall and people in the street would stare at him; I was annoyed that he enjoyed listening to his own voice, I couldn't even stand the name Mayakovsky ... sounding so much like a cheap pen name."[10] Both Mayakovsky's persistent adoration and rough appearance irritated her. It was, allegedly, to please her, that Mayakovsky attended a dentist, started to wear a bow tie and use a walking stick.[8]

Soon after Osip Brik published A Cloud in Trousers in September 1915, Mayakovsky settled in the Palace Royal hotel at the Pushkinskaya Street, Petrograd, not far from where they lived. He introduced the couple to his Futurist friends and the Briks' flat quickly evolved into a modern literary salon. From then on Mayakovsky was dedicating every one of his large poems (with the obvious exception of Vladimir Ilyich Lenin) to Lilya; such dedications later started to appear even in the texts he had written before they met, much to her displeasure.[10] In summer 1918, soon after Lilya and Vladimir starred in the film Encased in a Film (only fragments of which survived), Mayakovsky and the Briks moved in together. In March 1919 all three came to Moscow and in 1920 settled in a flat at the Gondrikov Lane, Taganka.[36]

In 1920, Mayakovsky had a brief romance with Lilya Lavinskaya, an artist who also contributed to ROSTA. She gave birth to a son, Gleb-Nikita Lavinsky (1921–1986), later a Soviet sculptor.[37] In 1922 Lilya Brik fell in love with Alexander Krasnoshchyokov, the head of the Soviet Prombank. This affair resulted in the three months' rift, which was to some extent reflected in the poem About That (1923). Brik and Mayakovsky's relationships ended in 1923, but they never parted. "Now I am free from placards and love", he confessed in the poem called "For the Jubilee" (1924). Still, when in 1926 Mayakovsky was granted a state-owned flat at the Gendrikov Lane in Moscow, all three of them moved in and lived there until 1930, having turned the place into the LEF headquarters.[30]

Mayakovsky continued to profess his devotion to Lilya whom he considered a family member. It was Brik who in the mid-1930s famously addressed Stalin with a personal letter which made all the difference in the way the poet's legacy has been treated since in the USSR. Still, she had many detractors (among them Lyudmila Mayakovskaya, the poet's sister) who regarded her as an insensitive femme-fatale and cynical manipulator, who had never been really interested in either Mayakovsky or his poetry.[citation needed] "To me, she was a kind of monster. But Mayakovsky apparently loved her that way, armed with a whip", remembered poet Andrey Voznesensky who knew Lilya Brik personally.[36] Literary critic and historian Viktor Shklovsky who resented what he saw as the Briks' exploitation of Mayakovsky both when he lived and after his death, once called them "a family of corpse-mongers".[35]

In summer 1925, Mayakovsky traveled to New York, where he met Russian émigré Elli Jones, born Yelizaveta Petrovna Zibert, an interpreter who spoke Russian, French, German and English fluently. They fell in love, for three months were inseparable, but decided to keep their affair secret. Soon after the poet's return to the Soviet Union, Elli gave birth to daughter Patricia. Mayakovsky saw the girl just once, in Nice, France, in 1928, when she was three.[10]

Patricia Thompson, a professor of philosophy and women's studies at Lehman College in New York City, is the author of the book Mayakovsky in Manhattan, in which she told the story of her parents' love affair, relying on her mother's unpublished memoirs and their private conversations prior to her death in 1985. Thompson traveled to Russia after the collapse of the Soviet Union, looking for her roots, was welcomed there with respect and since then started to use her Russian name, Yelena Vladimirovna Mayakovskaya.[10]

In 1928, in Paris Mayakovsky met Russian émigré Tatyana Yakovleva,[11] a 22-year-old model working for the Chanel fashion house, and niece of painter Alexandre Jacovleff. He fell in love madly and wrote two poems dedicated to her, "Letter to Comrade Kostrov on the Essence of Love" and "Letter to Tatiana Yakovleva". Some argued that, since it was Elsa Triolet (Lilya's sister) who acquainted them, the liaison might have been the result of Brik's intrigue, aimed at stopping the poet from getting closer to Elli Jones and especially daughter Patricia, but the power of this passion apparently caught her by surprise.[36]

Mayakovsky tried to persuade Tatyana to return to Russia but she refused. In late 1929, he made an attempt to travel to Paris in order to marry his lover but was refused a visa for the first time, again, as many believed, due to Lilya's making full use of her numerous "connections". It became known that she "accidentally" read out a letter from Paris to Mayakovsky, alleging that Tatiana was getting married, even though, as it turned out soon, the latter's wedding was not on the agenda at that very moment.[citation needed] Lydia Chukovskaya insisted it was the "ever-powerful Yakov Agranov, another one of Lilya's lovers" who prevented Mayakovsky obtaining a visa, upon her request.[38]

In the late 1920s, Mayakovsky had two more affairs, with student (later Goslitizdat editor) Natalya Bryukhanenko (1905–1984) and with Veronika Polonskaya (1908–1994), a young MAT actress, then the wife of actor Mikhail Yanshin.[39]

It was Veronika's unwillingness to divorce the latter that resulted in her rows with Mayakovsky, the last of which preceded the poet's suicide.[40] Yet, according to Natalya Bryukhanenko, it was not Polonskaya but Yakovleva whom he was pining for. "In January 1929 Mayakovsky [told me] he … would put a bullet to his brain if he didn't see that woman any time soon", she later remembered. Which, on 14 April 1930, he did.[citation needed]

Works and critical reception

[edit]

Mayakovsky's early poems established him as one of the more original poets to come out of the Russian Futurism, a movement rejecting the traditional poetry in favour of formal experimentation, and welcoming the social change promised by modern technology. His 1913 verses, surreal, seemingly disjointed and nonsensical, relying on forceful rhythms and exaggerated imagery with the words split into pieces and staggered across the page, peppered with street language, were considered unpoetic in literary circles at the time.[12] While the confrontational aesthetics of his fellow Futurist group members' poetry were mostly confined to formal experiments, Mayakovsky's idea was creating the new, "democratic language of the streets".[15]

In 1914, his first large work, an avant-garde tragedy Vladimir Mayakovsky came out. The fierce critique of the city life and capitalism in general was, at the same time, a paean to the modern industrial power, featuring the protagonist sacrificing himself for the sake of the people's happiness in the future.[4][13]

In September 1915, A Cloud in Trousers came out,[19] Mayakovsky's first major poem of appreciable length; it depicted the subjects of love, revolution, religion and art, written from the vantage point of a spurned lover. The language of the work was the language of the streets, and Mayakovsky went to considerable lengths to debunk idealistic and romanticized notions of poetry and poets.

Вашу мысль |

Your thoughts, |

| —From the prologue of A Cloud in Trousers |

Backbone Flute (1916) outraged contemporary critics. Its author has been described as "talentless charlatan," spurning "empty words of a malaria sufferer"; some even recommended that he'd "be hospitalized immediately."[10] In retrospect it is seen as a groundbreaking piece, introducing the new forms of expressing social anger and personal frustrations.[15]

The period from 1917 to 1921 was a fruitful one for Mayakovsky, who greeted the Bolshevik Revolution with a number of poetic and dramatic works, starting with "Ode to the Revolution" (1918) and "Left March" (1918), a hymn to the proletarian might, calling for the fight against the "enemies of the revolution."[15] Mystery-Bouffe (1918; revised version, 1921), the first Soviet play, told the story of a new Noah's Ark, built by the "unclean" (workers and peasants) sporting "moral cleanness" and "united by the class solidarity."[12][15]

From 1919 to 1921, Mayakovsky worked for the Russian Telegraph Agency (ROSTA). Painting posters and cartoons, he provided them with rhymes and slogans (mixing rhythm patterns, different typesetting styles, and using neologisms) which were describing the currents events in dynamics.[8][14] In three years he produced some 1100 pieces he called "ROSTA Windows".[15]

In 1921, Mayakovsky's poem 150 000 000 came out, which hailed the Russian people's mission in igniting the world revolution, but failed to impress Lenin. The latter praised the 1922 poem "Re Conferences" (Прозаседавшиеся), a scathing satire on the nascent Soviet bureaucracy starting to eat up the apparently flawed state system.[5]

Mayakovsky's poetry was saturated with politics, but the love theme in the early 1920s became prominent too, mainly in I Love (1922) and About That (1923), both dedicated to Lilya Brik, whom he considered a family member even after the two drifted apart, in 1923.[14] In October 1924 appeared Vladimir Ilyich Lenin written on the death of the Soviet Communist leader.[11][14] While the newspapers reported of highly successful public performances, the Soviet literary critics had their reservations, G. Lelevich calling it "cerebral and rhetorical," Viktor Pertsov described it as wordy, naïve and clumsy.[41]

Mayakovsky's extensive foreign trips resulted in the books of poetry (The West, 1922–1924; Paris, 1924–1925: Poems About America, 1925–1926), as well as a set of analytical satirical essays.[5]

In 1926, Mayakovsky wrote and published "Talking with the Taxman about Poetry", the first in a series of works criticizing the new Soviet philistinism, the result of the New Economic Policy.[16] His 1927 epic All Right! sought to unite heroic pathos with lyricism and irony. Extoling the new Bolshevik Russia as "the springtime of the human kind" it was praised by Lunacharsky as "the October Revolution set in bronze."[14][15]

During the last three years of his life, Mayakovsky completed two satirical plays: The Bedbug (1929), and The Bathhouse, both lampooning bureaucratic stupidity and opportunism.[14] The latter was extolled by Vsevolod Meyerhold who rated it as high as the best work of Moliere, Pushkin and Gogol and called it "the greatest phenomenon of the history of the Russian theatre."[23] The fierce criticism both plays were met with in the Soviet press was overstated and politically charged, but still, in retrospect Mayakovsky's work in the 1920s is regarded as patchy, even Vladimir Ilyich Lenin and All Right! being inferior to his passionate and innovative 1910s work. Several authors, among them Valentin Katayev and close friend Boris Pasternak, reproached him for squandering enormous potential on petty propaganda. Marina Tsvetayeva in her 1932 essay "The Art in the Light of Conscience" left a particularly sharp comment on Mayakovsky's death: "For twelve years Mayakovsky the man has been destroying Mayakovsky the poet. On the thirteenth year the Poet rose up and killed the man… His suicide lasted twelve years, not for a moment he pulled the trigger."[42]

Legacy

[edit]After Mayakovsky's death the Association of the Proletarian Writers' leadership made sure the publications of the poet's work were cancelled and his very name stopped being mentioned in the Soviet press. In her 1935 letter to Joseph Stalin, Lilya Brik challenged her opponents, asking personally the Soviet leader for help. Stalin's resolution inscribed upon this message, read:

Comrade Yezhov, please take charge of Brik's letter. Mayakovsky is the best and the most talented poet of our Soviet epoch. Indifference to his cultural heritage amounts to a crime. Brik's complaints are, in my opinion, justified...[43]

The effect of this letter was startling. Mayakovsky was instantly hailed a Soviet classic, proving to be the only member of the artistic avant-garde of the early 20th century to enter the Soviet mainstream. His birthplace of Baghdati in Georgia was renamed Mayakovsky in his honour. In 1937 the Mayakovsky Museum (and library) were opened in Moscow.[15] Triumphal Square in Moscow became Mayakovsky Square.[16] In 1938 the Mayakovskaya Metro Station was opened to the public. Nikolay Aseyev received a Stalin prize in 1941 for his poem "Mayakovsky Starts Here", which celebrated him as a poet of the revolution.[8] In 1974 the Russian State Museum of Mayakovsky opened in the center of Moscow in the building where Mayakovsky resided from 1919 to 1930.[44]

As a result, for the Soviet readership Mayakovsky became just "the poet of the Revolution". His legacy has been censored, more intimate or controversial pieces ignored, lines taken out of contexts and turned into slogans (like the omnipresent "Lenin lived, Lenin lives, Lenin shall live forever"). The major rebel of his generation was turned into a symbol of the repressive state. The Stalin-sanctioned canonization dealt Mayakovsky a second death, according to Boris Pasternak, as the communist authorities "started to impose him forcibly, like Catherine the Great did with potatoes."[45] In the late 1950s and early 1960s Mayakovsky's popularity in the Soviet Union started to rise again, with the new generation of writers recognizing him as a purveyor of artistic freedom and daring experimentation. "Mayakovsky's face is etched on the altar of the century," Pasternak wrote at that time.[10] Young poets, drawn to avant-garde art and activism that often clashed with communist dogma, chose Mayakovsky's statue in Moscow for their organized poetry readings.[14]

Among the Soviet authors he influenced were Valentin Kataev, Andrey Voznesensky (who called Mayakovsky a teacher and favorite poet and dedicated a poem to him entitled Mayakovsky in Paris)[46][47] and Yevgeny Yevtushenko.[48] In 1967 the Taganka Theater staged the poetical performance Listen Here! (Послушайте!), based on Mayakovsky's works with the leading role given to Vladimir Vysotsky, who was also much inspired by Mayakovsky's poetry.[49]

Mayakovsky became well-known and studied outside of the USSR. Poets such as Nâzım Hikmet, Louis Aragon and Pablo Neruda acknowledged having been influenced by his work.[15] He was the most influential futurist in Lithuania and his poetry helped to form the Four Winds movement there.[50] Mayakovsky was a significant influence on American poet Frank O'Hara. O'Hara's 1957 poem "Mayakovsky"(1957) contains many references to Mayakovsky's life and works,[51][52] in addition to "A True Account of Talking to the Sun at Fire Island" (1958), a variation on Mayakovsky's "An Extraordinary Adventure that Happened to Vladimir Mayakovsky One Summer at a Dacha" (1920).[53] 1986 English singer and songwriter Billy Bragg recorded the album Talking with the Taxman about Poetry, named after Mayakovsky's poem of the same name. In 2007 Craig Volk's stage bio-drama Mayakovsky Takes the Stage (based on his screenplay At the Top of My Voice) won the PEN-USA Literary Award for Best Stage Drama.[54]

In the Soviet Union's final years there was a strong tendency to view Mayakovsky's work as dated and insignificant; there were even calls for banishing his poems from school textbooks. Yet on the basis of his best works, Mayakovsky's reputation was revived[14] and attempts have been made (by authors like Yuri Karabchiyevsky) to recreate an objective picture of his life and legacy. Mayakovsky was credited as a radical reformer of the Russian poetic language who created his own linguistic system charged with the new kind of expressionism, which in many ways influenced the development of Soviet and world poetry.[15] The "raging bull of Russian poetry," "the wizard of rhyming," "an individualist and a rebel against established taste and standards," Mayakovsky is seen by many in Russia as a revolutionary force and a giant rebel in the 20th century Russian literature.[citation needed]

Bernd Alois Zimmermann included his poetry in his Requiem für einen jungen Dichter (Requiem for a Young Poet), completed in 1969.

There is a Mayakovsky monument in Kyrgyzstan, in a former Soviet sanatorium outside the capital Bishkek.

Poet Yegor Letov dedicated a poem titled "Self-withdrawal" to his suicide and has included verses of his in his poetry.

Bibliography

[edit]Poems

[edit]- A Cloud in Trousers (Облако в штанах, 1915)

- Backbone Flute (Флейта-позвоночник, 1915)

- The War and the World (Война и мир, 1917)

- The Man (Человек, 1918)

- 150 000 000 (1921)

- About That (Про это, Pro eto, 1923)

- Vladimir Ilyich Lenin (Владимир Ильич Ленин, 1924)

- A Flying Proletarian (Летающий пролетарий, 1925)

- All Right! (Хорошо!, 1927)

Poem cycles and collections

[edit]- The Early Ones (Первое, 1912–1924, 22 poems)

- I (Я, 1914, 4 poems)

- Satires. 1913–1927 (23 poems, including "Take That!", 1914)

- The War (Война, 1914–1916, 8 poems)

- Lyrics (Лирика, 1916, Лирика, 1916, 3 poems)

- Revolution (Революция, 1917–1928, 22 poems, including "Ode to Revolution", 1918; "The Left March", 1919)

- Everyday Life (Быт, 1921–1924, 11 poems, including "On Rubbish", 1921, "Re Conferences", 1922)

- The Art of the Commune (Искусство коммуны, 1918–1923, 11 poems, including "An Order to the Army of Arts", 1918)

- Agitpoems (Агитпоэмы, 1923, 6 poems, including "The Mayakovsky Gallery")

- The West (Запад, 1922–1925, 10 poems, including "How Does the Democratic Republic Work?", and the 8-poem Paris cycle)

- The American Poems (Стихи об Америке, 1925–1926, 21 poems, including "The Brooklyn Bridge")

- On Poetry (О поэзии, 1926, 7 poems, including "Talking with the Taxman About Poetry", "For Sergey Yesenin")

- The Satires. 1926 (Сатира, 1926. 14 poems)

- Lyrics. 1918–1924 (Лирика. 12 poems, including "I Love", 1922)

- Publicism (Публицистика, 1926, 12 poems, including "To Comrade Nette, a Steamboat and a Man", 1926)

- The Children's Room (Детская, 1925–1929. 9 poems for children, including "What Is Good and What Is Bad")

- Poems. 1927–1928 (56 poems, including "Lenin With Us!")

- Satires. 1928 (Сатира. 1928, 9 poems)

- Cultural Revolution (Культурная революция, 1927–1928, 20 poems, including "Beer and Socialism")

- Agit…(Агит…, 1928, 44 poems, including "'Yid'")

- Roads (Дороги, 1928, 11 poems)

- The First of Five (Первый из пяти, 1925, 26 poems)

- Back and Forth (Туда и обратно, 1928–1930, 19 poems, including "The Poem of the Soviet Passport")

- Formidable Laughter (Грозный смех, 1922–1930; more than 100 poems, published posthumously, 1932–1936)

- Poems, 1924–1930 (Стихотворения. 1924–1930, including "A Letter to Comrade Kostrov on the Essence of Love", 1929)

- Whom Shall I Become? (Кем Быть, Kem byt'?, published posthumously 1931, poem for children, illustrated by N. A. Shifrin)

Plays

[edit]- Vladimir Mayakovsky (Владимир Маяковский. Subtitled: Tragedy, 1914)

- Mystery-Bouffe (Мистерия-Буфф, 1918)

- The Bedbug (Клоп, 1929)

- The Bathhouse (Баня. 1930)

- Moscow Burns. 1905 (Москва горит. 1905, 1930)

Essays and sketches

[edit]- My Discovery of America (Мое открытие Америки, 1926), in four parts

- How to Make Verses (Как делать стихи, 1926)

Filmography

[edit]- Not Born for Money (Не для денег родившийся, 1918)

- Fettered by Film (Закованная фильмой, 1918)

- Lady and the Hooligan (Барышня и хулиган, 1918)

Translations

[edit]- Mayakovsky, Vladimir. The Bedbug and selected poetry. Ed. with introd. by Patricia Blake. Trans. by Max Hayward and George Reavey. New York: Meridian Books, 1960. Reprint: Indiana University Press, 1975.

- Mayakovsky, Vladimir. Mayakovsky: Plays. Trans. Guy Daniels. (Northwestern University Press, Evanston, Il, 1995). ISBN 0-8101-1339-2.

- Mayakovsky, Vladimir. For the voice (The British Library, London, 2000).

- Mayakovsky, Vladimir (ed. Bengt Jangfeldt, trans. Julian Graffy). Love is the heart of everything : correspondence between Vladimir Mayakovsky and Lili Brik 1915–1930 (Polygon Books, Edinburgh, 1986).

- Mayakovsky, Vladimir (comp. and trans. Herbert Marshall). Mayakovsky and his poetry (Current Book House, Bombay, 1955).

- Mayakovsky, Vladimir. Selected works in three volumes (Raduga, Moscow, 1985).

- Mayakovsky, Vladimir. Selected poetry. (Foreign Languages, Moscow, 1975).

- Mayakovsky, Vladimir (ed. Bengt Jangfeldt and Nils Ake Nilsson). Vladimir Majakovsky: Memoirs and essays (Almqvist & Wiksell Int., Stockholm 1975).

Literature

[edit]- Aizlewood, Robin. Verse form and meaning in the poetry of Vladimir Maiakovsky: Tragediia, Oblako v shtanakh, Fleita-pozvonochnik, Chelovek, Liubliu, Pro eto (Modern Humanities Research Association, London, 1989).

- Brown, E. J. Mayakovsky: a poet in the revolution (Princeton Univ. Press, 1973).

- Charters, Ann & Samuel. I love : the story of Vladimir Mayakovsky and Lili Brik (Farrar Straus Giroux, NY, 1979).

- Humesky, Assya. Majakovskiy and his neologisms (Rausen Publishers, NY, 1964).

- Jangfeldt, Bengt. Majakovsky and futurism 1917–1921 (Almqvist & Wiksell International, Stockholm, 1976).

- Lavrin, Janko. From Pushkin to Mayakovsky, a study in the evolution of a literature. (Sylvan Press, London, 1948).

- Novatorskoe iskusstvo Vladimira Maiakovskogo (trans. Alex Miller). Vladimir Mayakovsky: Innovator (Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1976).

- Noyes, George Rapall (ed.). Masterpieces of the Russian drama. Vol. 2 (Dover Pub., NY, 1961 [1933]).

- Nyka-Niliūnas, Alfonsas. Keturi vėjai ir keturvėjinikai (The Four Winds literary movement and its members), Aidai, 1949, No. 24. (in Lithuanian)

- Rougle, Charles. Three Russians consider America : America in the works of Maksim Gorkij, Aleksandr Blok, and Vladimir Majakovsky (Almqvist & Wiksell International, Stockholm, 1976).

- Shklovskii, Viktor Borisovich. (ed. and trans. Lily Feiler). Mayakovsky and his circle (Dodd, Mead, NY, 1972).

- Stapanian, Juliette. Mayakovsky's cubo-futurist vision (Rice University Press, 1986).

- Terras, Victor. Vladimir Mayakovsky (Twayne, Boston, 1983).

- Vallejo, César (trans. Richard Schaaf) The Mayakovsky case (Curbstone Press, Willimantic, CT, 1982).

- Volk, Craig, "Mayakovsky Takes The Stage" (full-length stage drama), 2006 and "At The Top Of My Voice" (feature-length screenplay), 2002.

- Wachtel, Michael. The development of Russian verse : meter and its meanings (Cambridge University Press, 1998).

References

[edit]- ^ Mayakovsky, Vladimir (1985). "Conversation with Comrade Lenin". Selected Works in Three Volumes. Vol. 1 (Selected Verse). English poem trans. Irina Zheleznova. USSR: Raduga Publishers. pp. 238. ISBN 5-05-00001 7-3.

On snow-covered lands / and stubbly fields, / in smoky plants / and on factory sites, / with you in our hearts, / Comrade Lenin, / we think, / we breathe, / we live, / we build, / and we fight!

- ^ Mayakovsky, Vladimir (1960). "At the Top of My Voice". The Bedbug and Selected Poetry. trans. Max Hayward and George Reavey. New York: Meridian Books. pp. 231–235. ISBN 978-0253201898.

When I appear / before the CCC / of the coming / bright years, / by way of my Bolshevik party card, / I'll raise / above the heads / of a gang of self-seeking / poets and rogues, / all the hundred volumes / of my / communist-committed books.

- ^ a b c Sundaram, Chantal (2000). Manufacturing Culture: The Soviet State and the Mayakovsky Legend 1930–1993. Ottawa, Canada: National Library of Canada: Acquisitions and Bibliographical Services. pp. 71, 85. ISBN 0-612-50061-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Iskrzhitskaya, I.Y. (1990). "Vladimir Vladimirovich Mayakovsky". Russian Writers. Biobibliographical dictionary. Vol.2. Prosveshchenye. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g Mikhaylov, Al. (1988). "Mayakovsky". Lives of Distinguished People. Molodaya Gvardiya. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- ^ "ФЭБ: Маяковский. Из беседы с сотрудником газеты «Прагер пресс». — 1961". feb-web.ru. Archived from the original on 25 July 2018. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- ^ Я знаю: / глупость – эдемы и рай! / Но если / пелось про это, // должно быть, / Грузию, радостный край, / подразумевали поэты.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Liukkonen, Petri. "Vladimir Mayakovsky". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011.

- ^ I, Myself (autobiography). The Works by Vladimir Mayakovsky in 6 volumes. Ogonyok Library. Pravda Publishers. Moscow, 1973. Vol.I, pp.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "The Raging Bull of Russian Poetry". Haaretz. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z "V.V. Mayakovsky biography. Timeline". The Lives of the Distinguished People series. Issue No.700. Molodaya Gvardiya, Moscow. 1988. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Vladimir Mayakovsky". www.poets.org. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Vladimir mayakovsky. Biography". The New Literary net. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Vladimir Vladimirovich Mayakovsky". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Vladimir Vladimirovich Mayakovsky. Biography". Mayakovsky site. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- ^ a b c d "Vladimir Mayakovsky biography. Timeline". max.mmlc.northwestern.edu. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- ^ Lawton, Anna (1988). Russian Futurism Through Its Manifestoes, 1912 – 1928. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. pp. 51–52. ISBN 0-8014-9492-3.

- ^ Commentaries to Autobiography (I, Myself). The Works by Vladimir Mayakovsky in 6 volumes. Ogonyok Library. Pravda Publishers. Moscow, 1973. Vol.I, p.455

- ^ a b "A Cloud in Trousers (Part 1) by Vladimir Mayakovsky". vmlinux.org. Archived from the original on 21 June 2008. Retrieved 7 April 2010.

- ^ Petrić, Vlada. Constructivism in Film: The Man With the Movie Camera:A Cinematic Analysis. Cambridge University Press. 1987. Page 32. ISBN 0-521-32174-3

- ^ Jangfeldt, Bengt (1976). Majakovskij and Futurism 1917-21 (PDF). Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell International. Retrieved 23 December 2018.

- ^ Arutcheva, V., Paperny, Z. "Commentaries to About That". The Complete V.V.Mayakovsky in 13 volumes. Khudozhestvennaya Literatura. Moscow, 1958. Vol. 4. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Fevralsky, A. (1958). "Commentaries to Баня (The Bathhouse)". The Complete V.V.Mayakovsky in 13 volumes. Khudozhestvennaya Literatura. Moscow, 1957. Vol. 11. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- ^ Mayakovsky, Vladimir (1925). "Mexico". Trans. Adam Halbur and Andrew Krizhanovsky.

- ^ Shakarian, Pietro A. "Mayakovsky in Cleveland: A Fiery Futurist's Discovery of the Forest City". Cleveland Historical. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ McSmith, Andy (2015). Fear and the Muse Kept Watch, The Russian Masters - from Akhmativa and Pasternak to Shostakovich and Eisenstein - Under Stalin. New York: New Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-59558-056-6.

- ^ Woroszylsk, Viktor (1971). The Life of Mayakovsky. New York: The Orion Press. pp. 438–84.

- ^ McSmith, Andy (2015). Fear and the Muse Kept Watch, The Russian Masters - from Akhmativa and Pasternak to Shostakovich and Eisenstein - Under Stalin. New York: New Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-59558-056-6.

- ^ Woroszylsk, Viktor (1971). The Life of Mayakovsky. New York: The Orion Press. p. 527.

- ^ a b Katanyan, Vasily (1985). "Mayakovsky. The Chronology, 1893–1930 // Маяковский: Хроника жизни и деятельности". Moscow. Sovetsky Pisatel Publishers. Retrieved 1 May 2015.

- ^ a b Polonskaya, Veronika (1938). "Remembering V. Mayakovsky". Izvestia (1990). Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- ^ Belyayeva Dina. "B. Маяковский-Любовная лодка разбилась о быт... En" [V. Mayakovsky – The Love Boat smashed up on the dreary routine ... En]. poetic translations (in Russian and English). Stihi.ru – national server of modern poetry. Retrieved 7 April 2010.

- ^ Kotkin, Stephen (6 November 2014). Stalin: Volume I: Paradoxes of Power, 1878–1928. Penguin. ISBN 9780698170100. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- ^ "Vladimir Mayakovsky. Odd One Out. The First TV Channel premier". Archived from the original on 22 July 2013.

- ^ a b "The Briks. The Little 'Swede' Family / Брик Лиля и Брик Осип. Шведская семейка. Quotes". ArtMisto. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- ^ a b c Oboymina, E., Tatkova, A. "Lilya Brik and Vladimir Mayakovsky". Russian Biographies. Archived from the original on 27 June 2015. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Moscow Graves. Lavinsky, N.A". Archived from the original on 3 May 2013.

- ^ Chukovskaya, Lydia. Notes on Akhmatova. 1957–1967. P. 547

- ^ "Mayakovsky Remembered by Women Friends. Compiled, edited by Vasily Katanyan". Druzhba Narodov. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- ^ "The Very Veronika Polonskaya". Sovetsky Ekran (Soviet Screen) magazine interview, No. 13, 1990

- ^ Katanyan, Vasily. Life and Work Timeline, 1893–1930. Year 1925. Moscow. Sovetsky Pisatel (5th edition).

- ^ Zaytsev, S. (2012). "The Lyrical Shot". Tatyanin Den. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- ^ Katanyan, Vasily (1998) Memoirs. p. 112

- ^ "Museum". mayakovsky.info.

- ^ Zaytsev, S. (2012). "Mayakovsky's Second Death". Tatyanin Den. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- ^ Андрей Вознесенский. Маяковский в Париже [Andrei Voznesensky. Mayakovsky in Paris] (in Russian). Ruthenia.ru. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- ^ Огонек: Как Нам Было Страшно! [Spark: How It was terrible!] (in Russian). Ogoniok.com. Archived from the original on 12 February 2012. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- ^ Евгений Евтушенко: "Как поэт я хотел соединить Маяковского и Есенина" | Культура – Аргументы и Факты [Yevgeny Yevtushenko: "As a poet, I would like to connect Mayakovsky and Esenin»] (in Russian). Aif.ru. 23 April 2008. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- ^ Театр на Таганке: Высоцкий и другие [Taganka Theater: Vysotsky and other] (in Russian). Taganka.theatre.ru. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- ^ "tekstai". Tekstai.lt. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- ^ "Mayakovsky by Frank O'Hara : The Poetry Foundation". www.poetryfoundation.org. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

I am standing in the bath tub/ crying. Mother, mother" "That's funny! there's blood on my chest / oh yes, I've been carrying bricks /what a funny place to rupture! "with bloody blows on its head. / I embrace a cloud, / but when I soared / it rained.

- ^ Mayakovsky, Vladimir (2008). "A Cloud in Trousers, I Call". Backbone Flute: Selected Poetry of Vladimir Mayakovsky. trans. Andrey Kneller. Boston: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1438211640.

Mother? / Mother! / Your son has a wonderful sickness! / Mother!" " I walked on, enduring the pain in my chest. / My ribcage was trembling under the stress." "Not a man – but a cloud in trousers.

- ^ "Brad Gooch: On "A True Account of Talking to the Sun at Fire Island" | Modern American Poetry". www.modernamericanpoetry.org. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- ^ "PEN Center USA Literary Awards Winners". Archived from the original on 15 November 2017. Retrieved 3 April 2012.

External links

[edit]- Works by or about Vladimir Mayakovsky at the Internet Archive

- Works by Vladimir Mayakovsky at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Vladimir Mayakovsky Archive at marxists.org

- English translations of three early poems

- English translation of two poems, "So This is How I Turned Into a Dog” and “Hey!”

- English translation of “To His Beloved Self….”

- Rhymed English translation of "Backbone Flute"

- Includes English translations of two poems, 127–128

- A recording of Mayakovsky reading "An Extraordinary Adventure..." in Russian, English translation provided

- "A Show-Trial," an excerpt from Mayakovsky: A Biography by Bengt Jangfeldt, 2014.

- Isaac Deutscher, The Poet and the Revolution, 1943.

- Chapter on Russian Futurists incl Mayakovsky in Trotsky's Literature and Revolution

- The 'raging bull' of Russian poetry article by Dalia Karpel at Haaretz.com, 5 July 2007

- Vladimir Mayakovsky at IMDb

- The State Museum of V.V. Mayakovsky at Google Cultural Institute

- Newspaper clippings about Vladimir Mayakovsky in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- The Motherland will Notice her Terrible Mistake: Paradox of Futurism in Jasienski, Mayakovsky and Shklovsky

- 1893 births

- 1930 deaths

- People from Baghdati

- People from Kutais Governorate

- Russian Social Democratic Labour Party members

- Old Bolsheviks

- Russian communist writers

- Russian communist poets

- Futurist writers

- Modernist theatre

- Russian avant-garde

- Russian dramatists and playwrights

- Russian male dramatists and playwrights

- Russian Futurism

- Russian-language poets

- Russian Marxists

- Russian people of Ukrainian descent

- Russian male poets

- Russian male stage actors

- Russian male film actors

- Russian male silent film actors

- Socialist realism writers

- Soviet dramatists and playwrights

- Soviet male writers

- 20th-century Russian poets

- 20th-century Russian male writers

- Soviet poets

- 1930 suicides

- Suicides by firearm in the Soviet Union

- Suicides by firearm in Russia

- Burials at Novodevichy Cemetery

- Russian poets of Ukrainian descent

- 20th-century Russian painters

- Russian male painters

- Russian Marxist writers

- Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture alumni

- Stroganov Moscow State Academy of Arts and Industry alumni

- Atheists from Georgia (country)

- Atheists from the Russian Empire

- Russian atheists

- 20th-century atheists