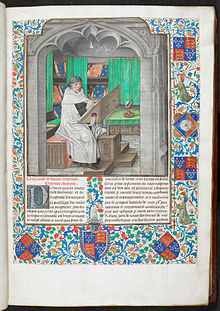

Vincent of Beauvais

Vincent of Beauvais (Latin: Vincentius Bellovacensis or Burgundus; French: Vincent de Beauvais; c. 1184/1194 – c. 1264) was a Dominican friar at the Cistercian monastery of Royaumont Abbey, France.[1] He is known mostly for his Speculum Maius (Great mirror), a major work of compilation that was widely read in the Middle Ages. Often retroactively described as an encyclopedia or as a florilegium,[2] his text exists as a core example of brief compendiums produced in medieval Europe.[3]

Biography

[edit]The exact dates of his birth and death are unknown, and not much detail has surfaced concerning his career. Conjectures place him first in the house of the Dominicans at Paris between 1215 and 1220, and later at the Dominican monastery founded by Louis IX of France at Beauvais in Picardy. It is more certain, however, that he held the post of "reader" at the monastery of Royaumont on the Oise, not far from Paris, also founded by Louis IX, between 1228 and 1235. Around the late 1230s, Vincent had begun working on the Great Mirror and in 1244 he had completed the first draft.[4] The king read the books that Vincent compiled and supplied the funds for procuring copies of such authors as he required. Queen Margaret of Provence and her son-in-law, Theobald V of Champagne and Navarre, are also named among those who urged him to the composition of his "little works", especially De morali principis institutione.[5] In the late 1240s, Vincent was working on his Opus which included On the Education of Noble Girls (De Eruditione Filiorum Nobilium). In this work he styles himself as "Vincentius Belvacensis, de ordine praedicatorum, qualiscumque lector in monasterio de Regali Monte".[5] Though Vincent may have been summoned to Royaumont before 1240, there is no evidence that he lived there before the return of Louis IX and his wife from the Holy Land.[5] It is possible that he left Royaumont in 1260,[6] which is also the approximate year that he wrote Tractatus Consolatorius, which was occasioned by the death of the king's son Louis that year.[5] Between the years 1260 and 1264 Vincent sent the first completed book of the Opus to Louis IX and Thibaut V.[6] In 1264 he died.

Great Mirror (Speculum Maius)

[edit]

What is known of Vincent and his historical importance largely depends on his compendium Speculum Maius or the Great Mirror. He worked on it for approximately 29 years (1235–1264)[7] in the pursuit of presenting a compendium of all of the knowledge available at the time. He collected the materials for the work from Île-de-France libraries, and there is evidence to suggest even further than that.[8] He found support for the creation of the Great Mirror from the Dominican order to which he belonged as well as King Louis IX of France.[8] The metaphor of the title has been argued to "reflect" the microcosmic relations of Medieval knowledge. In this case, the book mirrors "both the contents and organization of the cosmos".[9] Vincent himself stated that he chose "Speculum" for its name because his work contains "whatever is worthy of contemplation (speculatio), that is, admiration or imitation".[10] It is by this name that the compendium is connected to the medieval genre of speculum literature.

Other works

[edit]- Universal Work on the Royal Condition (Opus universale de statu principis) was described as a guideline to "provide instructions for the behaviors and duties of the prince, his family, and his court".[11] It was to be a four-part treatise, although only the first, The moral instruction of a prince, and the fourth, The education of noble children, were completed.

- The Moral Instruction of a Prince or On the Foundations of Royal Morals (De morali Principis institutione) (1260-1263), written for King Louis IX of France on the topic of kingship.[12]

- The Education of Noble Children (De eruditione filiorum nobilium) (1249).[13] This pedagogical treatise has also been viewed as a sermon expanding on the biblical passage Ecclesiasticus 7:25-26: "You have sons? Train them and care for them from boyhood. You have daughters? Guard their bodies and do not show a joyful face to them."[14] The majority of the text deals with the education of boys, with roughly one-fifth of the text devoted to the education of girls. The text is notable for being "the first medieval educational text to both systematically present a comprehensive method of instruction for lay children and to included a section devoted to girls."[11]

- Expositio in orationem dominicam (Exposition on the Lord’s Prayer)[15]

- Liber consolatorius ad Ludovicum regem de morte filii (Book to Console King Louis after the Death of His Son), (1260)[15]

- Liber de laudibus beatae Virginis (The Book Praising the Blessed Virgin)[15]

- Liber de laudibus Johannis Evangelistae (The Book Praising John the Evangelist)[15]

- Liber de sancta Trinitate or Tractatus de sancta trinitate (The Book of the Holy Trinity), (1259-1260)[13]

- Liber gratiae (The Book of Grace), (1259-1260)[13]

- Memoriale temporum (Chronicle of the Times)[16]

- Sermones manuals de tempore. (Johann Koelhoff d. Ä., Cologne c. 1482 digitized)

- Tractatus de poenitentia (Treatise on Penance)[15]

- Tractatus in salutatione beatae Virginis Mariae ab angelo facta (Treastie on the Salutation to the Blessed Virgin Mary Made by the Angel)[15]

There are manuscript copies and modern editions of De eruditione filiorum nobilium, De morali principis institutione, Liber consolatorius ad Ludovicum regem de morte filii. There are only manuscript copies of Liber de sancta Trinitate, Memoriale temporum, Tractatus de poenitentia, and Tractatus in salutatione beatae Virginis Mariae ab angelo facta.[17]

Beyond the thirteen works that can be confidently accredited to Vincent,[18] there is the possibility of a lost work named Tractatus de vitio detractionis (Treastise on the Sin of Omission)[15] and the apocryphal fourth part to the Great Mirror, Speculum morale.[19]

Along with Conradus of Altzheim, Henricus Suso, Ludolphus of Saxony, the authorship of Speculum Humanae Salvationis has been sometimes attributed to Vincent.[20]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Vincent de Beauvais" (in French). Arlima Archives de littérature du moyen âge. Retrieved January 29, 2018.

- ^ Franklin-Brown, Mary (2012). Reading the world : encyclopedic writing in the scholastic age. Chicago London: The University of Chicago Press. p. 9. ISBN 9780226260709.

- ^ Binkley, Peter (1997). Pre-modern encyclopaedic texts : proceedings of the second COMERS Congress, Groningen, 1-4 July 1996. Leiden New York: Brill. p. 48. ISBN 9789004108301.

- ^ Jacobs-Pollez, Rebecca (2012). The education of noble girls in medieval france: Vincent of beauvais and "De eruditione filiorum nobilium" (PhD). University of Missouri - Columbia. p. 234. ProQuest 1266044945.

- ^ a b c d Archer 1911, p. 90.

- ^ a b Jacobs-Pollez 2012, p. 235.

- ^ Franklin-Brown 2012, p. 11.

- ^ a b Franklin-Brown 2012, p. 95.

- ^ Harris-McCoy, Daniel (2008). Varieties of encyclopedism in the early Roman Empire: Vitruvius, Pliny the Elder, Artemidorus (Ph.D). University of Pennsylvania. p. 116. ProQuest 304510158.

- ^ Franklin-Brown 2012, p. 271.

- ^ a b Jacobs-Pollez 2012, p. iv.

- ^ Robert J., Schneider; Rouse, Richard H. (1991). "The Medieval Circulation of the De morali principis institutione of Vincent of Beauvais". Viator. 22: 189–228. doi:10.1484/J.VIATOR.2.301322.

- ^ a b c Jacobs-Pollez 2012, p. 234.

- ^ Tobin, Rosemary Barton (1974). "Vincent of Beauvais on the Education of Women". Journal of the History of Ideas. 35 (3): 485–489. doi:10.2307/2708795. JSTOR 2708795.

- ^ a b c d e f g Jacobs-Pollez 2012, p. 21.

- ^ Jacobs-Pollez 2012, p. 22.

- ^ Jacobs-Pollez 2012, p. 236-237.

- ^ Jacobs-Pollez 2012, p. 20.

- ^ Jacobs-Pollez 2012, p. 237.

- ^ Wilson, Adrian; Lancaster Wilson, Joyce (1984). A Medieval Mirror: Speculum Humanae Salvationis 1324–1500. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-0520051942.

- Attribution

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Archer, Thomas Andrew (1911). "Vincent of Beauvais". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 90, 91.

Further reading

[edit]- Brother Potamian (1913). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- A. Gabriel, The Educational Ideas of Vincent of Beauvais (2d ed., 1962)

- L. Thorndike. A History of Magic and Experimental Science. During the First Thirteen Centuries of our Era (1929) vol 2 ch 56 pp 457–76, a detailed study of the science coverage

- P. Throop, Vincent of Beauvais: The Education of Noble Children (Charlotte, VT: MedievalMS, 2011)

- P. Throop, Vincent of Beauvais: The Moral Instruction of a Prince (Charlotte, VT: MedievalMS, 2011)

External links

[edit]- A Vincent of Beauvais website.

- A concise bibliography of Vincent de Beauvais' works (Archives de littérature du Moyen Âge - Arlima).

- Works by or about Vincent of Beauvais at the Internet Archive

- Speculum naturale (Google Books), Hermannus Liechtenstein, 1494.

- (in French) A chronology about life, works and context of Vincent of Beauvais Archived 2014-04-28 at the Wayback Machine and a study bibliography about the De morali principis institutione Archived 2014-04-28 at the Wayback Machine, on the personal page of Emmanuel Wald Archived 2014-06-06 at the Wayback Machine ((in English and French)).

- Works of Vicent of Beauvais at Somni:

- Works of Vicente de Beauvais at the National Library of Portugal