Trade during the Viking Age

While the Vikings are perhaps best known for accumulating wealth by plunder, tribute, and conquest, they were also skilled and successful traders. The Vikings developed several trading centres both in Scandinavia and abroad as well as a series of long-distance trading routes during the Viking Age (c. 8th Century AD to 11th Century AD). Viking trading centres and trade routes would bring tremendous wealth and plenty of exotic goods such as Arab coins, Chinese Silks, and Indian Gems.[1]: 10 Vikings also established a "bullion economy" in which weighed silver, and to a lesser extent gold, was used as a means of exchange. Evidence for the centrality of trade and economy can be found in the criminal archaeological record through evidence of theft, counterfeit coins, and smuggling.[2] The Viking economy and trade network also effectively helped rebuild the European economy after the fall of the Roman Empire [1]: 123

Trade routes

[edit]The Norse Vikings had a big, expansive and planned out trade network. Trade took place on a gold level and over short and long distances. Improvements in ship technology and cargo capabilities made trade and the transport of goods much easier,[3][1]: 97 especially as Europe began to shift to a bulk economy.[1]: 128 The majority of trade was conducted among the several ports that lined the Scandinavian coasts,[4] and the routes were well enough established that they were frequented by pirates looking to seize possessions.[3]: 27 Viking raids likely followed such established trade routes.[3]: 24

The Vikings also engaged in trade with merchants throughout Europe, Asia and the Far East.[5] The Volga and Dnieper Trade Routes were the two main trade routes that connected Northern Europe with Constantinople, Jerusalem, Baghdad, and the Caspian Sea, and the end of the Silk Road. These trade routes not only brought luxury and exotic goods from the Far East but also an overwhelming amount of silver Arab coins that were melted down for silver and also used for trade.[1]: 103

Several trade routes disconnected Scandinavia with the Mediterranean with trade routes that ran through Central Europe and around the Iberian Peninsula.[6] In Iberia the first trade and exploration was likely in minerals due to the role that the region played in the Roman Period. The Iberian example shows how Viking were often traders and raiders, who in the aftermath of raids would use their newfound power to establish trade.[6]: 4-5 The Vikings also sent merchants as far west as Greenland and North America.[7]

Trade routes would play an important role in rebuilding the economy of Europe during the Viking Age. The collapse of the Roman Empire significantly reduced the European economy. Prior to the start of the Viking Age, trade had begun to rise again. However, it was highly dependent on bartering, meaning that all trade hinged on “a double coincidence of wants”. Viking trade and raids helped reintroduce coins and other valuable goods that were either traded for or stolen back into the economy. Such goods were reintroduced into the economy through either trade or markets that were set up by the Vikings for the purpose of selling plundered objects.[1]: 123

Trading towns

[edit]At the beginning of the Viking Age, the first proper trading towns developed in Scandinavia. These appeared in central locations along Scandinavia's coasts near natural harbors or fjords. Trading centers varied in size, character, and significance. Only a select few developed into international trading posts. Every town was ruled by a king who imposed taxes on imported and exported goods in exchange for military protection of the town's citizens.[4]

The largest trading centers during the Viking Age were Ribe (Denmark), Kaupang (Norway), Hedeby (Denmark), and Birka (Sweden) in the Baltic region.[7]

Hedeby was the largest and most important trading center. Located along the southern border of Denmark in the inner part of the Schlei Fjord, Hedeby controlled both the north–south trade routes (between Europe and Scandinavia) and the east–west routes (between the Baltic and the North Seas).[5] At its peak, Hedeby's population was around 1000 people.[4] Archaeological evidence from Hedeby suggests that the city's economic importance was of political significance as fortifications were erected in the tenth century to withstand numerous assaults.[1]: 107

Ribe, located on the West coast of Denmark, was established in the early 8th century as the eastern end of a trading and monetary network that stretched around the North Sea.[7] Many of the trading towns in the Baltic would begin to disappear shortly after the year 1000 as the continent shifted to a bulk economy that minimized the role of these centres. This was also parallel with the rise of royal power in the region.[1]: 128-129

Scandinavian York (Jórvík) was a major manufacturing centre, particularly in metalwork. Archaeological evidence indicates that it had a busy international trade with thriving workshops, and well-established mints. It had several routes to Norway and Sweden with onward connections to Byzantium and the Muslim world via the Dnieper and Volga rivers. It's craftspeople sourced their raw materials both near and far. There was gold and silver coming from Europe, copper and lead from the Pennines and tin from Cornwall. Also, there was amber, for the production of jewellery, coming from the Baltic and soapstone to make large cooking pots from Norway or Shetland . Wine was imported from the Rhineland with silk for the production of hats coming from Byzantium.[8]: 71–77 [9][10]

There were also several Viking trading centers located along several rivers in modern-day Russia and Ukraine including Gorodische, Gnezdovo, Cherigov, Novgorod, and Kyiv. These towns became major trade destinations on the trading route from the Baltic Sea to Central Asia.[7]

Trade and Settlement

[edit]Viking settlements also played an important role in Viking trade. In Viking settlements such as Ireland the first peaceful interactions between the Native Irish and the Vikings were economic in nature.[11] Silver hordes in Ireland containing coins from other corners of the Viking World also show how such settlements were very quickly incorporated into a new Global economy.[12]: 91 Here the initial strategic military significance of such settlements morphed into economic and political significance.[12]: 94 Place names also show the broader economic significance and impact of the Vikings. The Copeland Islands off the coast of Ireland bear the name of “Merchant Islands” in Old Norse. In Normandy linguistic patterns also suggest the centrality of trade in the Viking settlement as the only lasting Norse influence in the region is in language is both trade centric and trade specific.[13] In the Viking Greenland settlements it is also suspected that the walrus ivory trade may have been the primary means of economic sustenance for the populations there based on isotopic analysis of walrus ivory from around the Viking Diaspora.[14]

The development of large cargo ships allowed for the rise of bulk cargo transport across long distances. These new large cargo ships were introduced around 1000CE to Northern Europe and featured new technology of sails, reducing the need for rowers on the ships. The growing maritime connectivity, encouraged the spread of Latin and Christianity into areas of Scandinavia and Baltic Sea.[15]

Goods

[edit]Imports

[edit]Silver, silk, spices, weapons, wine, glassware, quern stones (for grinding grain), fine textiles, pottery, slaves, both precious and non-precious metals.[7][16][4][17]

Exports

[edit]Honey, tin, wheat, wool, various types of fur and hides, feathers, falcons, whalebone, walrus ivory, and other stud reindeer antler, and amber.[4][18][7][19]

Coinage

[edit]Coins played an important role in Viking age trade, with many of the coins that were used by Vikings coming from the Islamic world. More than 80,000 silver Viking age Arab silver dirhams have been found in Gotland, and another 40,000 found in mainland Sweden. These numbers are likely only a fraction of the total influx of Arab currency into Viking Age Scandinavia as a great deal of silver coins were also likely melted down to make other silver objects including ingots, ornaments, and jewelry.[1]: 103 [20] In Iceland, archaeological evidence suggests that while coins may not have been as prevalent as they were in Scandinavia, they still played an important role in daily life and as a status symbol.[21] Coins also carried symbolic power. A series of coins minted during the 9th century that were meant to look like coins from the Carolingian empire might have been intended for use as a political symbol for resisting its reach and influence.

Furs

[edit]The fur trade was an important piece of the Viking trade network. The furs often exchanged hands through a number of intermediaries enriching each. One of the routes that furs took was south and east into the Arab world where it was often highly priced. One Arab writer states that during the 10th century that “one black pelt reaches the price of 100 dinars.”[1]: 113

Slaves

[edit]Slaves were one of the most important trade items.[16] The Vikings bought and sold slaves throughout their trade network. Viking slaves were known as thralls. A good number of slaves were exported to the Islamic world.[7] In Viking Raids, slaves and captives were usually of great importance for both the monetary and labor value. In addition to being bought and sold slaves could be used to pay off debts,[3]: 106 and were often used as human sacrifices in religious ceremonies. A slave's price depend on their skills, age, health, and looks.[3]: 106

Many slaves were sold to slavery in the Abbasid Caliphate via the Bukhara slave trade because of the high demand. Many European Christians and Pagans were sold to them by the Vikings.[1]: 116 The slave trade also existed in Northern Europe as well were other Norse Men and Women were sold and held as slaves as well. Records from the life of Archbishop Timber suggest that this was quite common.[1]: 117 The Life of St. Anskar also suggests that slaves were a tradable commodity.[3]: 26 Individuals were often also held as captives for ransom instead of just being seized and sold into slavery.[6]: 11

In Northwestern Europe it is likely that Viking Age Dublin became the center of the Slave trade,[3]: 35 with one account from the Fragmentary Annals describing Vikings bringing “Blue Men” back from raids in the south as slaves. These slaves were likely Black African prisoners taken from raids in either North Africa or the Iberian peninsula.[6]: 56

People taken captive during the Viking raids in Europe could be sold to Moorish Spain via the Dublin slave trade[22] or transported to Hedeby or Brännö in Scandinavia and from there via the Volga trade route to Russia, where slaves and furs were sold to Muslim merchants in exchange for Arab silver dirham and silk, which have been found in Birka, Wollin and Dublin;[23] initially this trade route between Europe and the Abbasid Caliphate passed via the Khazar Kaghanate,[24] but from the early 10th-century onward it went via Volga Bulgaria and from there by caravan to Khwarazm, to the Samanid slave market in Central Asia and finally via Iran to the Abbasid Caliphate.[25] European slaves were popular in the Middle East where they were termed as saqaliba.

The slaves were often paid for with silver Arabic coins, which would then travel back along the Russian river trade routes back to Scandinavia, contributing to the silver hoard.[26]

Local Trade

[edit]Trade during the Viking Age also took place at the local level, primarily involving agriculture products such as vegetables, grains, and cereals. Domestic animals were also traded among local peoples. These items were brought into town by farmers and traded for basic necessities, such as tools and clothes, and luxury items, such as glassware and jewelry.[5]

Bullion economy

[edit]

The Viking Age saw the development of a bullion economy. In this economic framework, traders and merchants exchanged goods for bullion (precious metals, primarily gold and silver). Trade was usually accomplished by barter. Bullion lacked the formal quality control linked with coinage and therefore provided a highly flexible system.[27] The durability of silver and gold made them more suited for a monetary role than many other commodities.

By the 9th century, silver had become the basis for the Viking economy. Most of the silver was acquired from the Islamic world. When the silver mines near Baghdad ran dry in the late 10th century, the Vikings began to tap central Europe, specifically the Harz Mountains in Germany.[17] Bullion took the form of coins, ingots, and jewelry. The value of bullion was determined by its purity and mass. Methods used to test the purity of the metal included “pricking" and “pecking” the surface to test the hardness of the alloy and reveal plating. Determining bullion's mass required the use of weights and scales. Many of the bronze scales used by Viking traders folded on themselves making them compact and easy to carry for travel.[7]

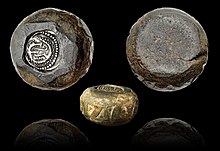

The two types of weights imported from foreign lands were cubo-octahedral weights (Dice weights) and oblate spheroids (barrel weights). Both were produced in various sizes with markings indicating the weights they represented. The majority of imported weights came from the Islamic world and contained Arabic inscriptions.[7]

Vikings also produced their own weights for measuring quantities of silver and gold. These lead weights were decorated with enameling, insert coins, or cut up ornamental metalwork.[citation needed] Unlike the dice weights or barrel weights, each lead weight was unique so there was no danger of them being rearranged or switched during the course of an exchange.[7]

Exchange rates

[edit]Estimated exchange rates at the beginning of the 11th century in Iceland were:

- 8 ounces of silver = 1 ounce of gold

- 8 ounces of silver = 4 milk cows

- 8 ounces of silver = 24 sheep

- 8 ounces of silver = 144 ells (roughly 72 meters) of wadmal 2 ells wide (about 1 meter)

- 12 ounces of silver = 1 adult male slave[4]

If the weight of a piece of jewelry was more than needed to complete a purchase, it was cut up into smaller bits until the correct weight needed for the transaction was reached. The term hack silver is used to describe these silver objects.[27]Silver ingots were primarily used for large/high-value transactions. The largest found weights weigh more than 1 kilogram each.[28]

Precious metals were also used to display personal wealth and status. For example, Rus traders symbolized their wealth through silver neck rings.[7] Silver or gold gifts were often exchanged to secure social and political relationships.[27][28]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Winroth, Anders (2014). The Age Of The Vikings. Princeton University Press.

- ^ Kalmring, Sven (2010). Of Thieves, Counterfeiters and Homicides: Crime in Hedeby and Birka.

- ^ a b c d e f g Wolf, Kristen (2004). Daily Life of the Vikings. Greenwood Press.

- ^ a b c d e f Short, William R. "Towns and Trading in the Viking Age". Hurstwic.org. Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- ^ a b c "Trade in the Viking Period". National Museum of Denmark. Archived from the original on 7 December 2013.

- ^ a b c d Christys, Ann (2015). Vikings In the South: Voyages to Iberia and the Mediterranean. Bloomsbury Academic.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Williams, Gareth; Pentz, Peter; Wemhoff, Matthias; Kleingärtner, Sunhild (2014). Vikings: Life and Legend. London: British Museum.

- ^ Fafinski, Mateusz (2014). "The moving centre: trade and travel in York from Roman to Anglo-Saxon Times". In Gale R. Owen-Crocker; Brian W. Schneider (eds.). The Anglo-Saxons: The World through their Eyes. pp. 71–77. ISBN 978-1407-31262-0.

- ^ Tweddle, Dominic (2017). "Foreign Trade" (PDF). Viking Age York: Trade. The Jorvik Viking Centre. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 February 2023. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ Cannon, J. (2009). York, kingdom of. The Oxford Companion to British History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-956763-8. Retrieved 17 February 2023.

- ^ Downham, Clare (2014). "Viking Settlements in Ireland before 1014". In Jón Viðar Sigurðsson; Timothy Bolton (eds.). Celtic-Norse Relationships in the Irish Sea in the Middle Ages 800 - 1200. The Northern World. Vol. 65. Brill.

- ^ a b Downham, Clare (2004). "The historical importance of Viking-Age Waterford". The Journal of Celtic Studies. 4: 71–96. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- ^ Abrams, Lesley (2013). "Early Normandy". Anglo-Norman Studies. 35: 51–52.

- ^ Frei, Karin M.; Coutu, Ashley N.; Smiarowski, Konrad; Harrison, Ramona; Madsen, Christian K.; Arneborg, Jette; Frei, Robert; Guðmundsson, Gardar; Sindbæk, Søren M.; Woollett, James; Hartman, Steven; Hicks, Megan; McGovern, Thomas H. (2015). "Was it for walrus? Viking Age settlement and medieval walrus ivory trade in Iceland and Greenland". World Archaeology. 47 (3): 439–466. doi:10.1080/00438243.2015.1025912. S2CID 59436423.

- ^ "Review for "Splitting and authentication of the newest retrieved cellulose-rich organic fiber from the exterior layer of Bangladeshi palmyra seed sprouts"". 2024-07-24. doi:10.1039/d4ra04030a/v1/review1.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b "Imports in the Viking Age". National Museum of Denmark. Archived from the original on 7 December 2013.

- ^ a b Graham-Campbell, James; Williams, Gareth (2007). Silver Economy in the Viking Age. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast.

- ^ "Vikings as Traders". SWIRK. Archived from the original on 28 March 2019.

- ^ Ashby, Steven P.; Coutu, Ashley N.; Sindbæk, Søren M. (April 2015). "Urban Networks and Arctic Outlands: Craft Specialists and Reindeer Antler in Viking Towns". European Journal of Archaeology. 18 (4): 679–704. doi:10.1179/1461957115Y.0000000003. S2CID 162119499.

- ^ Sheehan, John (1995). "Silver and Gold Hoards: Status, Wealth and Trade in the Viking Age". Archaeology Ireland. 9 (3): 19–22. ISSN 0790-892X.

- ^ Bell, Aidan (2009). Coins from Viking Age Iceland (PDF). The University of Iceland.

- ^ "The Slave Market of Dublin". 23 April 2013.

- ^ The New Cambridge Medieval History: Volume 3, C.900-c.1024. (1995). Storbritannien: Cambridge University Press. p. 91

- ^ The World of the Khazars: New Perspectives. Selected Papers from the Jerusalem 1999 International Khazar Colloquium. (2007). Nederländerna: Brill. p. 232

- ^ The New Cambridge Medieval History: Volume 3, C.900-c.1024. (1995). Storbritannien: Cambridge University Press. p. 504

- ^ Sheehan, John (2020-10-06), "Viking-Age bullion from southern Scandinavia and the Baltic region in Ireland", Viking-Age Trade, Title: Viking-age trade : silver, slaves and Gotland / edited by Jacek Gruszczyński, Marek Jankowiak and Jonathan Shepard.Description: Abingdon, Oxon ; New York, NY : Routledge, 2021. | Series: Routledge archaeologies of the Viking world: Routledge, pp. 415–433, ISBN 978-1-315-23180-8, retrieved 2024-11-06

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ a b c Williams, Gareth. "Viking Money". BBC. Retrieved 20 October 2022.

- ^ a b "Vikings Scales and Weights". Teaching History.org. The British Museum. Retrieved 25 October 2022.