Celtic F.C.

| ||||

| Full name | The Celtic Football Club[1][2] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nickname(s) | The Bhoys The Celts The Hoops | |||

| Founded | 6 November 1887 | |||

| Ground | Celtic Park | |||

| Capacity | 60,411 | |||

| Owner | Celtic PLC (LSE: CCP) | |||

| Chairman | Peter Lawwell | |||

| Manager | Brendan Rodgers | |||

| League | Scottish Premiership | |||

| 2023–24 | Scottish Premiership, 1st of 12 (champions) | |||

| Website | celticfc.com | |||

|

| ||||

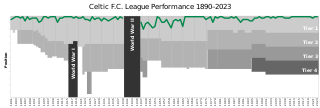

The Celtic Football Club, commonly known as Celtic (/ˈsɛltɪk/), is a professional football club in Glasgow, Scotland. The team competes in the Scottish Premiership, the top division of Scottish football. The club was founded in 1887[nb 1] with the purpose of alleviating poverty in the Irish–Scots population in the city's East End area. They played their first match in May 1888, a friendly match against Rangers which Celtic won 5–2. Celtic established themselves within Scottish football, winning six successive league titles during the first decade of the 20th century. The club enjoyed their greatest successes during the 1960s and 70s under Jock Stein, when they won nine consecutive league titles and the 1967 European Cup. Celtic have played in green and white throughout their history, adopting in 1903 the hoops that have been used ever since.

Celtic are one of only six clubs in the world to have won over 100 trophies.[4] The club has won the Scottish league championship 54 times, most recently in 2023–24, the Scottish Cup a record 42 times and the Scottish League Cup 21 times. The club's greatest season was 1966–67, when Celtic became the first British team to win the European Cup, also winning the Scottish league championship, the Scottish Cup, the League Cup and the Glasgow Cup. Celtic also reached the 1970 European Cup Final and the 2003 UEFA Cup Final, losing in both.

Celtic have a long-standing fierce rivalry with Rangers and, together, the clubs are known as the Old Firm. Their matches against each other are regarded as among the world's biggest football derbies. The club's fanbase was estimated in 2003 as being around 9 million worldwide and there are more than 160 Celtic supporters clubs in over 20 countries. An estimated 80,000 fans travelled to Seville for the 2003 UEFA Cup Final, and their "extraordinarily loyal and sporting behaviour" in spite of defeat earned the fans Fair Play awards from both FIFA[5] and UEFA.[6]

History

Celtic Football Club was formally constituted at a meeting in St. Mary's church hall in East Rose Street (now Forbes Street), Calton, Glasgow, by Irish Marist Brother Walfrid[7] on 6 November 1887, with the purpose of alleviating poverty in the East End of Glasgow by raising money for the charity Walfrid had instituted, the Poor Children's Dinner Table.[8] Walfrid's move to establish the club as a means of fund-raising was largely inspired by the example of Hibernian, which was formed out of the immigrant Irish population a few years earlier in Edinburgh.[9] Walfrid's own suggestion of the name Celtic (pronounced Seltik) was intended to reflect the club's Irish and Scottish roots and was adopted at the same meeting.[10][11] The club has the official nickname, The Bhoys. However, according to the Celtic press office, the newly established club was known to many as "the bold boys". A postcard from the early 20th century that pictured the team and read "The Bould Bhoys" is the first known example of the unique spelling. The extra h imitates the spelling system of Gaelic, wherein the letter b is often accompanied by the letter h.[12]

On 28 May 1888, Celtic played their first official match against Rangers and won 5–2 in what was described as a "friendly encounter".[13] Neil McCallum scored Celtic's first goal.[14] Celtic's first kit consisted of a white shirt with a green collar, black shorts, and emerald green socks.[15] The original club crest was a simple green cross on a red oval background.[15] In 1889 Celtic reached the final of the Scottish Cup in their first season taking part in the competition, but lost 2–1 to Third Lanark.[16] Celtic reached the final again in 1892 and this time were victorious after defeating Queen's Park 5–1, the club's first major honour.[17] Several months later the club moved to its new ground, Celtic Park, and in the following season won the Scottish League Championship for the first time.[13] In 1895, Celtic set the League record for the highest home score when they beat Dundee 11–0.[18]

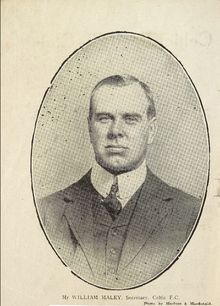

In 1897, the club became a private limited company[19] and Willie Maley was appointed as the first 'secretary-manager'.[20] Between 1905 and 1910, Celtic won the Scottish League Championship six times in a row.[13][21] They also won the Scottish Cup in both 1907 and 1908, the first times a Scottish club had ever won the double.[13][22] During World War I, Celtic won the league four times in a row, including 62 matches unbeaten between November 1915 and April 1917.[13][23] The mid-1920s saw the emergence of Jimmy McGrory as one of the most prolific goalscorers in British football history; over a sixteen-year playing career, he scored 550 goals in 547 games (including 16 goals for Clydebank during a season on loan in 1923–24), a British goal-scoring record to this day.[24][25] In January 1940, Willie Maley's retirement was announced. He was 71 years old and had served the club in varying roles for nearly 52 years, initially as a player and then as secretary-manager.[26][27] Jimmy McStay became manager of the club in February 1940.[28] He spent over five years in this role, although due to the Second World War no official competitive league football took place during this time. The Scottish Football League and Scottish Cup were suspended and in their place regional league competitions were set up.[29][30] Celtic did not do particularly well during the war years, but did win the Victory in Europe Cup held in May 1945 as a one-off football match to celebrate Victory in Europe Day.[31]

Ex-player and captain Jimmy McGrory took over as manager in 1945.[32] Under McGrory, Celtic defeated Arsenal, Manchester United and Hibernian to win the Coronation Cup, a one-off tournament held in May 1953 to commemorate the coronation of Elizabeth II.[33] He also led them to a League and Cup double in 1954.[34] On 19 October 1957, Celtic defeated Rangers in the final of the Scottish League Cup at Hampden Park in Glasgow, retaining the trophy they had won for the first time the previous year; the 7–1 scoreline remains a record win in a British domestic cup final.[35][36] The years that followed, however, saw Celtic struggle and the club won no more trophies under McGrory.[37]

Former Celtic captain Jock Stein succeeded McGrory in 1965.[38] He won the Scottish Cup in his first few months at the club,[39] and then led them to the League title the following season.[40]

1967 was Celtic's annus mirabilis. The club won every competition they entered: the Scottish League, the Scottish Cup, the Scottish League Cup, the Glasgow Cup, and the European Cup.[41][42] With this haul, Celtic became the first club to win the European Treble and remains the only club to win the fabled Quadruple.[43][44] Under the leadership of Stein, the club defeated Inter Milan 2–1 at the Estádio Nacional in Lisbon, on 25 May 1967 to become the first British team,[45][46] and indeed the first from outside Spain, Portugal and Italy to win the European Cup. They remain the only Scottish team to have reached the final. The players that day, all of whom were born within 30 miles of Glasgow, subsequently became known as the "Lisbon Lions".[47] The following season Celtic lost to Racing Club of Argentina in the Intercontinental Cup.[48]

Celtic reached the European Cup Final again in 1970, but were beaten 2–1 by Feyenoord at the San Siro in Milan.[49] The club continued to dominate Scottish football in the early 1970s, and their Scottish Championship win in 1974 was their ninth consecutive league title, equalling the joint world record held at the time by MTK Budapest and CSKA Sofia.[50]

Celtic enjoyed further domestic success in the 1980s, and in their Centenary season of 1987–88 won a Scottish Premier Division and Scottish Cup double.[51]

The club endured a slump in the early 1990s, culminating in the Bank of Scotland informing directors on 3 March 1994 that it was calling in the receivers as a result of the club exceeding a £5 million overdraft.[52] However, expatriate businessman Fergus McCann wrested control of the club, and ousted the family dynasties which had controlled Celtic since its foundation. According to media reports, McCann took over the club minutes before it was to be declared bankrupt.[53] McCann reconstituted the club business as a public limited company – Celtic PLC – and oversaw the redevelopment of Celtic Park into a 60,832 all-seater stadium. In 1998 Celtic won the title again under Dutchman Wim Jansen and prevented Rangers from beating their nine-in-a-row record.[54]

Martin O'Neill took charge of the club in June 2000.[55] Under his leadership, Celtic won three SPL championships out of five (losing the others by very small margins)[56] and in his first season in charge the club also won the domestic treble,[57] making O'Neill only the second Celtic manager to do so after Jock Stein.[58] In 2003, around 80,000 Celtic fans travelled to watch the club compete in the UEFA Cup Final in Seville.[59][60] Celtic lost 3–2 to Porto after extra time, despite two goals from Henrik Larsson during normal time.[61] The conduct of the thousands of travelling Celtic supporters received widespread praise from the people of Seville and the fans were awarded Fair Play Awards from both FIFA and UEFA "for their extraordinarily loyal and sporting behaviour".[62][63]

Gordon Strachan was announced as O'Neill's replacement in June 2005 and after winning the SPL title in his first year in charge,[64] he became only the third Celtic manager to win three titles in a row. He also guided Celtic to their first UEFA Champions League knockout stage in 2006–07[65] and repeated the feat in 2007–08[66] before departing the club in May 2009, after failing to win the SPL title.[67] Tony Mowbray took charge of the club in June 2009,[68] and he was succeeded a year later by Neil Lennon.[69] In November 2010, Celtic set an SPL record for the biggest win in SPL history, defeating Aberdeen 9–0 at Celtic Park.[70]

Celtic celebrated their 125th anniversary in November 2012, the same week as a Champions League match against Barcelona.[71] They won 2–1 on the night to complete a memorable week,[72] and eventually qualified from the group stages for the round of 16.[73] Celtic finished the season with the SPL and Scottish Cup double.[74] The club clinched their third consecutive league title in March 2014,[75] with goalkeeper Fraser Forster setting a new record during the campaign of 1,256 minutes without conceding a goal in a league match.[76] At the end of the season, manager Neil Lennon announced his departure from the club after four years in the role.[77]

Norwegian Ronny Deila was appointed manager of Celtic on 6 June 2014.[78][79] He went on to lead the team to two consecutive league titles and a League Cup, but the team's performances in European competition were poor. After being eliminated from the Scottish Cup by Rangers in April 2016, Deila announced he would leave the club at the end of the season.[80][81]

On 20 May 2016, Brendan Rodgers was announced as Deila's successor.[81][82] His first season saw the team go on a long unbeaten run in domestic competitions, during which time the club won their 100th major trophy, defeating Aberdeen 3–0 in the League Cup Final in November 2016.[83] Celtic also clinched their sixth successive league title in April 2017 with a record eight league games to spare,[84] and eventually finished with a record 106 points, becoming the first Scottish side to complete a top-flight league season undefeated since Rangers in 1899.[85][86] Celtic clinched their fourth treble by defeating Aberdeen 2–1 in the 2017 Scottish Cup Final, the result of which saw the club go through the entire domestic season unbeaten.[87]

Celtic continued their unbeaten domestic run into the following season, eventually extending it to 69 games, surpassing their own 100-year-old British record of 62 games, before finally losing to Hearts in November 2017.[88][89] Celtic retained the League Cup that same month by defeating Motherwell in the final,[90] and went on to clinch their seventh consecutive league title in April 2018.[91] They went on to defeat Motherwell again in the 2018 Scottish Cup Final to clinch a second consecutive domestic treble (the "double treble"), the first club in Scotland to do so.[92] Rodgers left the club midway through following season to join Leicester City;[93] Neil Lennon returned as caretaker manager for the rest of the season and helped Celtic secure an unprecedented third consecutive domestic treble (the "treble treble"), defeating Hearts 2–1 in the 2019 Scottish Cup Final.[94] Later that month, he was confirmed as the club's new manager.[95]

In December 2019, Lennon led Celtic to a 1–0 win over Rangers in the 2019 Scottish League Cup Final, the club's tenth consecutive domestic trophy.[96] By March 2020, Celtic were 13 points ahead in the league when professional football in Scotland was suspended due to the COVID-19 pandemic in the United Kingdom.[97][98] they were confirmed as champions in May 2020 following a SPFL board meeting where it was agreed that completing the full league campaign was infeasible.[99] The completion of the 2019–20 Scottish Cup was delayed, with the semi-finals and final – between Celtic and Hearts as in the previous year – not taking place until late autumn/winter of 2020. Celtic won on penalty-kicks after the sides tied at 3–3 after extra time, clinching a fourth successive treble.[100] However, Celtic struggled throughout the 2020–21 season with poor performances in Europe, knocked out of the League Cup by Ross County, and by February 2021 were trailing 18 points behind Rangers in the league – effectively ending their hopes of winning "ten in a row" league titles. Lennon resigned on 24 February 2021, with assistant manager John Kennedy taking interim charge of the team.[101] In the closing weeks of the season, Celtic were knocked out of the Scottish Cup by Rangers which condemned them to their first trophy-less season since 2010,[102] and finished the league campaign 25 points behind their Glasgow rivals.[103]

Crest and colours

For most of Celtic's history their home strip has featured green and white horizontal hoops, but their original strip consisted of a white top with black shorts and black and green hooped socks. The top also featured the Marist Brothers' badge on the right hand side, consisting of a green Celtic cross inside a red circle.[15][104] In 1889, the club changed to a green and white vertically striped top and for the next fourteen years this remained unchanged although the colour of the shorts alternated between white and black several times over this period. The top did not feature a crest.[15][105]

In 1903, Celtic adopted their now famous green and white hooped tops. The new design was worn for the first time on 15 August 1903 in a match against Partick Thistle.[15] Black socks continued to be worn until the early 1930s, at which point the team switched to green socks. Plain white socks came into use in the mid-1960s, and white has been the predominant colour worn since then.[15]

|

1888

|

1889–1903

|

1903–1932

|

1932–1965

|

1965 onwards

|

The club began using a badge in the 1930s, featuring a four leaf clover logo surrounded by the club's formal title, "The Celtic Football and Athletic Coy. Ltd".[106] However, it was not until 1977 that Celtic finally adopted the club crest on their shirts. The outer segment was reversed out, with white lettering on a green background on the team shirts. The text around the clover logo on the shirts was also shortened from the official club crest to "The Celtic Football Club".[106] For their centenary year in 1988, a commemorative crest was worn, featuring the Celtic cross that appeared on their first shirts. The 1977 version was reinstated for season 1989–90.[15]

From 1945 onwards numbered shirts slowly came into use throughout Scotland, before becoming compulsory in 1960. By this time Celtic were the last club in Britain to adopt the use of numbers on the team strip to identify players. The traditionalist and idealistic Celtic chairman, Robert Kelly, baulked at the prospect of the famous green and white hoops being disfigured, and as such Celtic wore their numbers on the players' shorts.[15] This unusual tradition survived until 1994, although numbered shirts were worn in European competition from 1975 onwards.[15] Celtic's tradition of wearing numbers on their shorts rather than on the back of their shirts was brought to an end when the Scottish Football League instructed Celtic to wear numbers on their shirts from the start of the 1994–95 season. Celtic responded by adding numbers to the top of their sleeves, however within a few weeks the football authorities ordered the club to attach them to the back of their shirts, where they appeared on a large white patch, breaking up the green and white hoops.[15]

In 1984 Celtic took up shirt sponsorship for the first time, with Fife-based double glazing firm CR Smith having their logo emblazoned on the front of the team jersey.[107][108] In season 1991–92, Celtic switched to Glasgow-based car sales company Peoples as sponsors.[109] The club failed to secure a shirt sponsor for season 1992–93, and for the first time since the early 1980s Celtic took to the field in 'unblemished' hoops.[110][111] Despite the loss of marketing revenue, sales of the new unsponsored replica top increased dramatically.[111] Celtic regained shirt sponsorship for season 1993–94, with CR Smith returning as shirt sponsors in a four-year deal.[107][112]

In 2005 the club severed their connection with Umbro, suppliers of their kits since the 1960s and entered into a contract with Nike. To mark the 40th anniversary of their European Cup win, a special crest was introduced for the 2007–08 season. The star that represents this triumph was retained when the usual crest was reinstated the following season.[15] In 2012, a retro style kit was designed by Nike that included narrower hoops to mark the club's 125th anniversary. A special crest was introduced with a Celtic knot design embroidered round the traditional badge. A third-choice strip based on the first strip from 1888 was also adopted for the season.[15]

In March 2015, Celtic agreed a new kit deal worth £30 million with Boston-based sportswear manufacturer New Balance to replace Nike from the start of the 2015–16 season.[113]

All of the kits for the 2017–18 season paid tribute to the Lisbon Lions, with the kits having a line on each side to represent the handles of the European Cup. The kits also included a commemorative crest, designed specifically for the season.[114] The regular crest was reinstated the following season, although the away strip featured a Celtic cross once again in reference to the club's heritage.[15]

In March 2020, Celtic announced a new five-year partnership with Adidas starting on 1 July 2020, in a deal believed to be the biggest kit sponsorship ever in Scottish sport.[115]

| Period[15] | Kit manufacturer[15] | Shirt sponsor (front)[15] | Shirt sponsor (back)[15] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1960s–1984 | Umbro | none | none |

| 1984–1991 | CR Smith | ||

| 1991–1992 | Peoples Ford | ||

| 1992–1993 | none | ||

| 1993–1997 | CR Smith | ||

| 1997–1999 | Umbro | ||

| 1999–2003 | NTL | ||

| 2003–2005 | Carling | ||

| 2005–2010 | Nike | ||

| 2010–2013 | Tennents | ||

| 2013–2015 | Magners | ||

| 2015–2016 | New Balance | ||

| 2016–2020 | Dafabet | Magners | |

| 2020– | Adidas |

Stadium

Celtic's stadium is Celtic Park, which is in the Parkhead area of Glasgow. Celtic Park, an all-seater stadium with a capacity of 60,411,[116] is the largest football stadium in Scotland and the eighth-largest stadium in the United Kingdom, after Murrayfield, Old Trafford, Twickenham, Wembley, the London Stadium, Tottenham Hotspur Stadium and the Millennium Stadium. It is commonly known as Parkhead[117] or Paradise.[118][119]

Celtic opened the original Celtic Park in the Parkhead area in 1888.[120] The club moved to a different site in 1892, however, when the rental charge was greatly increased.[121] The new site was developed into an oval shaped stadium, with vast terracing sections.[122] The record attendance of 83,500 was set by an Old Firm derby on 1 January 1938.[121] The terraces were covered and floodlights were installed between 1957 and 1971.[121] The Taylor Report mandated that all major clubs should have an all-seated stadium by August 1994.[123] Celtic was in a bad financial position in the early 1990s and no major work was carried out until Fergus McCann took control of the club in March 1994. He carried out a plan to demolish the old terraces and develop a new stadium in a phased rebuild, which was completed in August 1998. During this development, Celtic spent the 1994–95 season playing at the national stadium Hampden Park, costing the club £500,000 in rent.[124] The total cost of the new stadium on its completion was £40 million.[125]

Celtic Park has been used as a venue for Scotland internationals and Cup Finals, particularly when Hampden Park has been unavailable.[126] Before the First World War, Celtic Park hosted various other sporting events, including composite rules shinty-hurling,[127] track and field and the 1897 Track Cycling World Championships.[121] Open-air masses,[121] and First World War recruitment drives have also been held there.[128] In more recent years, Celtic Park has hosted the Opening Ceremonies of the 2014 Commonwealth Games,[129] the 2005 Special Olympics National Games and the 1990 Special Olympics European Games.[130] Celtic Park has occasionally been used for concerts, including performances by The Who and U2.[131]

In July 2016, Celtic Park became the first British football stadium to have a "rail seating" (safe standing) area in the ground. Rail seating is particularly common in Germany's Bundesliga, most notably at Borussia Dortmund's Westfalenstadion, a ground with a reputation on par with Celtic Park for its intensity and atmosphere.[132][133][134]

In June 2018, Celtic announced a series of stadium improvements that would be implemented before the 2018–19 season. These include the installation of new LED floodlights and a new entertainment system, a stadium-wide PA system and a new hybrid playing surface.[135]

Supporters

In 2003 Celtic were estimated to have a fan base of nine million people, including one million in the US and Canada.[136] There are over 160 Celtic Supporters Clubs in over 20 countries around the world.[137]

An estimated 80,000 Celtic supporters, many without match tickets, travelled to Seville in Spain for the UEFA Cup Final in May 2003.[62][63][138] The club's fans subsequently received awards from UEFA and FIFA for their behaviour at the match.[59][60][62][63][139]

Celtic has the highest average home attendance of any Scottish club.[140] They also had the 12th highest average league attendance out of all the football clubs in Europe in 2011.[141] A study of stadium attendance figures from 2013 to 2018 by the CIES Football Observatory ranked Celtic at 16th in the world during that period, and their proportion of the distribution of spectators in Scotland at 36.5%, the highest of any club in the leagues examined.[142]

In October 2013, French football magazine So Foot [fr] published a list of whom they considered the "best" football supporters in the world. Celtic fans were placed third, the only club in Britain on the list, with the magazine highlighting their rendition of "You'll Never Walk Alone" before the start of European ties at Celtic Park.[143]

On 23 October 2017, Celtic fans were awarded with the FIFA Fan Award for their tifo commemorating the 50th anniversary of the club's European cup win. The award celebrates the best fan moment of November 2016 to August 2017.[144]

Sectarianism

Celtic's traditional rivals are Rangers; collectively, the two clubs are known as the Old Firm[145] and seen by some as the world's biggest football derby.[146][147] The two have dominated Scottish football's history;[145] between them, they have won the Scottish league championship 108 times (as of May 2023) since its inception in 1890 – all other clubs combined have won 19 championships.[148] The two clubs are also by far the most supported in Scotland, with Celtic having the sixth highest home attendance in the UK during the 2014–15 season.[149][150] Celtic have a historic association with the people of Ireland and Scots of Irish descent, both of whom are mainly Roman Catholic.[151] Traditionally fans of rivals Rangers came from Scottish or Northern Irish Protestant backgrounds and support Unionism in Ireland.[151]

The clubs have attracted the support of opposing factions in the Troubles in Northern Ireland. Some supporters use songs, chants and banners at matches to abuse or show support for the Protestant or Catholic religions and proclaim support for Northern Irish paramilitary groups such as the IRA and UVF.[152]

There have been over 400 Old Firm matches played.[153] The games have been described as having an "atmosphere of hatred, religious tension and intimidation which continues to lead to violence in communities across Scotland."[152] The rivalry has fuelled many assaults and even deaths on Old Firm Derby days. Admissions to hospital emergency rooms have been reported to increase ninefold over normal levels[154] and in the period from 1996 to 2003, eight deaths in Glasgow were directly linked to Old Firm matches, and hundreds of assaults.[154][155]

Both sets of fans fought on the pitch after Celtic's victory in the 1980 Scottish Cup Final at Hampden Park.[156] There was serious fan disorder during an Old Firm match played in May 1999 at Celtic Park; missiles were thrown by Celtic fans, including one which struck referee Hugh Dallas, who needed medical treatment and a small number of fans invaded the pitch.[157]

Celtic have taken measures to reduce sectarianism. In 1996, the club launched its Bhoys Against Bigotry campaign, later followed by Youth Against Bigotry to "educate the young on having ... respect for all aspects of the community – all races, all colours, all creeds".[158]

Irish republicanism

Some groups of Celtic fans have expressed their support for Irish republicanism and the Irish Republican Army by singing or chanting about them at matches.[159][160]

In 2008 and 2010, there were protests by groups of fans over the team wearing the poppy for Remembrance Day, as the symbol is opposed by Irish Republicans owing to its association with the British military.[161][162] Celtic expressed disapproval of these protests, saying they were damaging to the image of the club and its fans, and pledged to ban those involved.[162] In 2011, UEFA and the Scottish Premier League investigated the club over pro-IRA chants by fans at different games. UEFA fined Celtic £12,700, while the SPL took no action, as the club had taken all reasonable action to prevent the chants.[163]

Celtic media

In 1965, Celtic began publishing its own newspaper, The Celtic View, now the oldest club magazine in football.[164] It was the brainchild of future chairman Jack McGinn, who at the time was working in the circulation department of Beaverbrook Newspapers.[165] McGinn himself edited the paper for the first few years, with circulation initially reaching around 26,000 copies.[166] By 2020, it was a 72-page glossy magazine with over 6,000 weekly readers, and the top selling club magazine in the United Kingdom. In the spring of 2020, the magazine saw a temporary cease of production due to the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK.[167] However, in August 2021, Celtic announced the restart of the production activities for the magazine, which was turned into a 100-page, quarterly publication.[168]

From 2002, Celtic's Internet TV channel Channel67 (previously known as Celtic Replay) broadcast Celtic's own content worldwide and offered live match coverage to subscribers outside the UK. It also provided three online channels. In 2004, Celtic launched their own digital TV channel called Celtic TV, which was available in the UK through Setanta Sports on satellite and cable platforms. Due to the collapse of Setanta in the UK in June 2009, Celtic TV stopped broadcasting, although the club hoped to find a new broadcast partner.[169] In 2011, Celtic TV was relaunched as an online service and replaced Channel 67.[170][171]

Influence on other clubs

Due to Celtic's large following, several clubs have emulated or been inspired by Celtic. As the club has a large following, especially in Northern Ireland, several clubs have been founded there by local Celtic fans. The most notable and successful was Belfast Celtic, formed in 1891 simply as Celtic. Upon incorporation as a limited company in 1901, however, the club adopted the name "Belfast Celtic", the title "Celtic Football Club Ltd" already being registered by the Glasgow club.[172] Their home from the same year was Celtic Park on Donegall Road in west Belfast, known to the fans as Paradise.[173] It was one of the most successful teams in Ireland until it withdrew from the Irish League in 1949.[174] Donegal Celtic, currently playing in the NIFL Premier Intermediate League,[175] was established in 1970,[176] with the Celtic part being taken on due to the massive local following for Scotland's Celtic and formerly Belfast Celtic.[177][178] They are nicknamed The Wee Hoops and play at Donegal Celtic Park on Suffolk Road in Belfast.[176] A club by the name of Lurgan Celtic was originally formed in 1903, with the obvious slant of aiming towards the Roman Catholic community of the town, adopting the name and colours of the Glaswegian Celtic.[179] The County Armagh club currently plays in the NIFL Championship.[180] In the Republic of Ireland, both Tuam Celtic A.F.C. and Castlebar Celtic F.C. play at grounds called Celtic Park.[181][182]

Throughout Scotland and England, other clubs have been named after and adopted Celtic's kit. These include the now defunct Scottish club Blantyre Celtic F.C.;[183] Irish club Listowel Celtic F.C.;[citation needed] and English lower-league clubs Cleator Moor Celtic F.C., which was founded in 1908–09 by Irish immigrants employed in the local iron ore mines,[184] Celtic Nation F.C. (now defunct)[185][186] and West Allotment Celtic F.C.[187] Somerset club Yeovil Town F.C., who traditionally wore an all-green shirt, modified their uniform to emulate Celtic's, inspired by the Scottish club's 2003 UEFA Cup run.[188]

South African club Bloemfontein Celtic F.C., one of the most popular club in the country with a large fan base in the Free State, is also named after Celtic F.C. Founded in 1969 as Mangaung United, in 1984, the then owner Molemela took over the club and changed the name to Bloemfontein Celtic. Based in Bloemfontein, they play in the Premier Soccer League.[189] In the United States of America, Hurricanes F.C. of Houston, Texas rebranded as Celtic FC America in 2019 and play in the Texas Premier Soccer League.[190]

Amateur Australian club South Lismore Celtic FC, which plays in the FFNC Premier League, the top league of the Football Far North Coast region, are named and designed after Celtic. South Lismore Celtic FC were the 2022 champions of the FFNC Premier League.

Charity

Celtic was initially founded to raise money for the poor in the East End of Glasgow and the club still retain strong charitable traditions today.[191] In 1995 the Celtic Charity Fund was formed with the aim of "revitalising Celtic's charitable traditions" and by September 2013 had raised over £5 million.[192][193] The Charity Fund has since then merged with the Celtic Foundation, forming the Celtic FC Foundation, and continues to raise money for local, national and international causes.[194][195]

On 9 August 2011 Celtic held a testimonial match in honour of former player John Kennedy. Due to the humanitarian crisis in East Africa, the entire proceeds were donated to Oxfam. An estimated £300,000 was raised.[196]

Celtic hold an annual charity fashion show at Celtic Park. In 2011 the main beneficiaries were Breast Cancer Care Scotland.[193]

Yorkhill Hospital is another charity with whom Celtic are affiliated and in December 2011 the club donated £3000 to it. Chief Executive Peter Lawwell said that; "Celtic has always been much more than a football club and it is important that, at all times we play an important role in the wider community. The club is delighted to have enjoyed such a long and positive connection with Yorkhill Hospital."[197]

Ownership and finances

Private company

Celtic were formed in 1887, and in 1897 the club became a Private Limited Company with a nominal share capital of 5000 shares at £1 each.[13][198] The following year a further share issue of 5000 £1 shares was created to raise more capital. The largest number of shares held were by businessmen from the East End of Glasgow, notably James Grant, an Irish publican and engineer, James Kelly, one of the club's original players turned publican, and John Glass, a builder and driving force in the early years of the club.[198] His shares, upon his death in 1906, passed on to Thomas White.[199] The Grant, Kelly and White families' shareholdings dominated ownership of the club throughout the 20th century.[200][201][202]

The late 1940s saw Robert Kelly, son of James Kelly, become chairman of the club after having been a director since 1931. Desmond White also joined the board around this time, upon the death of his father Thomas White.[203] By the 1950s, a significant number of shares in the club had passed to Neil and Felicia Grant, who lived in Toomebridge, County Antrim. These shares accounted for more than a sixth of the club's total issue.[204] Club chairman Robert Kelly's own family share-holding was of a similar size, and he used his close relationship with the Toomebridge Grants to ensure his power base at Celtic was unchallengeable.[204] When Neil Grant died in the early 1960s, his shareholding passed to his sister Felicia, leaving her as the largest share-holder in Celtic.[204][205] This gave rise to the myth among Celtic supporters of the "old lady in Ireland" who supposedly had the ultimate say in the running of the club.[204]

Celtic's board of directors had a reputation of being miserly and authoritarian. In particular they were known for frequently selling their top players and not paying their staff enough; they were also seen as lacking ambition, which caused friction with several managers.[206] Jimmy McGrory's tenure as manager is generally considered a period of underachievement, but with Chairman Robert Kelly's domineering influence. many have questioned how much authority McGrory ever had in team selection.[207][208] Even Jock Stein's time as manager ended on a sour note when he was offered a place on the Celtic board, but in a role involving ticket sales. Stein felt that this was demeaning, stating he was "a football man, not a ticket salesman". He declined this offer and decided to stay in football management, joining Leeds United instead.[209][210][211] Billy McNeill won a trophy in each of his five seasons as manager, but was still paid less than the managers of Rangers, Aberdeen and Dundee United. He left the club in June 1983 after his request for a contract and pay rise was publicly rebuffed by the board. McNeill moved on to manage Manchester City, stating that to remain at Celtic would have been humiliating.[210] McNeill's successor, Davie Hay, also had his difficulties with the Celtic board. When trying to sign players in 1987 to strengthen his squad to compete with high-spending Rangers, the board refused to pay for them; chairman Jack McGinn was quoted as saying that if Hay wanted these players, "he will have to pay for them himself".[212]

By the end of the 1980s the Celtic board consisted of chairman McGinn and directors Kevin Kelly, Chris White, Tom Grant and Jimmy Farrell. Neither McGinn nor Farrell were members of the traditional family dynasties at Celtic. Farrell was a partner in the Shaughnessy law firm that had long-standing connections with Celtic, and was invited to become a director in 1964. McGinn had set up The Celtic View in the 1960s and later became the club's commercial manager. He was given a seat on the board and became chairman in 1986.[213] In May 1990 the former Lord Provost of Glasgow, Michael Kelly, and property developer Brian Dempsey were invited to join the Celtic board.[214][215] Dempsey did not last long however, as a dispute about a proposed relocation to Robroyston resulted in him being voted off the board five months later.[216]

McCann takeover and transition to plc

Throughout the 1960s and 70s Celtic had been one of the strongest clubs in Europe. However, the directors failed to accompany the wave of economic development facing football in the 1980s, although the club continued to remain successful on the field, albeit limited to the domestic scene in Scotland.[217] In 1989, the club's annual budget was £6.4 million, about a third as much as Barcelona, with a debt of around 40% and on-field success deteriorating.[202] In the early 1990s the situation began to worsen as playing success declined dramatically and the club slipped further into debt.[217]

In 1993 fans began organising pressure groups to protest against the board, one of the most prominent being "Celts for Change". They supported a takeover bid led by Canadian-based businessman Fergus McCann and former director Brian Dempsey. Football writer Jim Traynor described McCann's attempt to buy the club as "good against evil".[218] Despite declining attendances and increasing unrest amongst supporters, the Kelly, White and Grant family groupings continued to guard their control of Celtic.[217][202]

On 4 March 1994, McCann bought Celtic for £9 million, finally wresting control from the family dynasties that had run the club for almost 100 years.[219][220] When he bought the club it was reported to be within 24 hours of entering receivership due to exceeding a £5 million overdraft with the Bank of Scotland.[200][219] He turned Celtic into a public limited company through a share issue which raised over £14 million, the most successful share issue in British football history.[200][221] He also oversaw the building of a new stadium, the 60,000 seater Celtic Park, which cost £40 million and at the time was Britain's largest club stadium.[125][200][222] This allowed Celtic to progress as a club because over £20 million was being raised each year from season ticket sales.[200]

McCann had maintained that he would only be at Celtic for five years and in September 1999 he announced that his 50.3% stake in Celtic was for sale. McCann had wanted the ownership of Celtic to be spread as widely as possible and gave first preference to existing shareholders and season-ticket holders, to prevent a new consortium taking over the club.[223] 14.4 million shares were sold by McCann at a value of 280 pence each. McCann made £40 million out of this, meaning he left Celtic with a £31 million profit. During his tenure, turnover at Celtic rose by 385% to £33.8m and operating profits rose from £282,000 to £6.7m.[125] McCann was often criticised during his time at Celtic and many people disagreed with him over building a stadium which they thought Celtic could not fill, not investing enough in the squad and being overly focused on finance. However, McCann was responsible for the financial recovery of the club and for providing a very good platform for it to build on. After he left Celtic, the club were able to invest in players and achieved much success such as winning the treble in 2000–01 and reaching the 2003 UEFA Cup Final.[125][200]

After McCann's exit, Irish billionaire Dermot Desmond was left as the majority shareholder. He purchased 2.8 million of McCann's shares to increase his stake in the club from 13% to 20%.[224]

In 2005, Celtic issued a share offer designed to raise £15 million for the club; 50 million new shares were made available priced at 30p each. It was also revealed that majority shareholder Desmond would buy around £10 million worth of the shares. £10 million of the money raised was for building a new training centre and youth academy, expanding the club's global scouting network and investing in coaching and player development programmes. The rest of the money was to be used to reduce debt. Building a youth academy was important for Celtic to surpass both Hearts and Rangers who had superior youth facilities at the time.[225] The share issue was a success and Celtic had more applicants than shares available,[226] The new Lennoxtown training centre was opened in October 2007.[227]

Celtic have been ranked in the Deloitte Football Money League six times. This lists the top 20 football clubs in the world according to revenue. They were ranked between 2002 (2000–01 season), 2006 (2004–05 season) and 2008 (2006–07 season).[228][229]

Celtic's financial results for 2011 showed that the club's debt had been reduced from £5.5 million to £500,000 and that a pre-tax profit of £100,000 had been achieved, compared with a loss of over £2 million the previous year. Turnover also decreased by 15% from £63 million to £52 million.[230]

In May 2012, Celtic were rated 37th in Brand Finance's annual valuation of the world's biggest football clubs. Celtic's brand was valued at $64 million (£40.7 million), $15 million more than the previous year. It was the first time a Scottish club had been ranked in the top 50. Matt Hannagan, Sports Brand Valuation Analyst at Brand Finance, said that Celtic were constrained by the amount of money they got from the SPL and that if they were in the Premiership then, due to their large fan base, they could be in the top 10 clubs in the world.[231][232] Later that month David Low, the financial consultant who advised Fergus McCann on his takeover of Celtic in 1994, said that Celtic's 'enterprise value' (how much it would cost to buy the club) was £52 million.[233]

Players

First-team squad

- As of 30 August 2024[234]

Note: Flags indicate national team as defined under FIFA eligibility rules. Players may hold more than one non-FIFA nationality.

|

|

Out on loan

Note: Flags indicate national team as defined under FIFA eligibility rules. Players may hold more than one non-FIFA nationality.

|

|

Academy squads

For more details on the academy squads, see Celtic F.C. B Team and Academy.

Women's team

Celtic have a pathway for female players, from eleven years old upwards.[235] In 2007 the club launched their women's first team, sometimes known as Celtic Women. The women's team reached the Scottish Women's Cup Final in their first season, and won their first trophy in 2010, the Scottish Women's Premier League Cup.[236] In December 2018 they announced a move to full-time training, becoming the first professional women's football team in Scotland.[237]

Former players

For further information, see List of Celtic F.C. players for players with over 100 appearances or other stated notability, List of Celtic F.C. international footballers and Category:Celtic FC players for a general list of ex-players.

Club captains

For further information, see Celtic club captains

|

|

Greatest ever team

| Greatest ever Celtic team |

In 2002 the greatest ever Celtic team was voted by supporters:[239]

Ronnie Simpson

Ronnie Simpson Danny McGrain

Danny McGrain Tommy Gemmell

Tommy Gemmell Bobby Murdoch

Bobby Murdoch Paul McStay

Paul McStay Billy McNeill – Voted Celtic's greatest ever captain

Billy McNeill – Voted Celtic's greatest ever captain Bertie Auld

Bertie Auld Jimmy Johnstone – Voted Celtic's greatest ever player

Jimmy Johnstone – Voted Celtic's greatest ever player Bobby Lennox

Bobby Lennox Kenny Dalglish

Kenny Dalglish Henrik Larsson – Voted Celtic's greatest ever foreign player

Henrik Larsson – Voted Celtic's greatest ever foreign player

Club officials

Board of directors

|

Management

|

Managerial history

|

|

Halls of Fame

Scotland Football Hall of Fame

As of 1 June 2020,[update] 27 Celtic players and managers have entered the Scottish Football Hall of Fame:[243]

- Roy Aitken

- Bertie Auld

- Stevie Chalmers

- John Clark

- Jim Craig

- Paddy Crerand

- Sir Kenny Dalglish MBE

- Jimmy Delaney

- Bobby Evans

- Tommy Gemmell

- Mo Johnston

- Jimmy Johnstone

- Paul Lambert

- Henrik Larsson

- Bobby Lennox

- Willie Maley

- Danny McGrain

- Jimmy McGrory

- Billy McNeill

- Paul McStay

- Bobby Murdoch

- Charlie Nicholas

- Ronnie Simpson

- Jock Stein CBE

- Gordon Strachan

- John Thomson

- Willie Wallace

Scotland Roll of Honour

The Scotland national football team roll of honour recognises players who have gained 50 or more international caps for Scotland. Inductees to have played for Celtic are:[244]

- Roy Aitken (50)

- Tom Boyd (66)

- Scott Brown (52)

- Gary Caldwell (17)

- John Collins (32)

- Kenny Dalglish MBE (47)

- Craig Gordon (14)

- Danny McGrain MBE (62)

- Paul McStay (76)

- Kenny Miller (7)

Numbers in brackets indicate the number of caps the above players won whilst at Celtic.[245]

Scottish Sports Hall of Fame

In the Scottish Sports Hall of Fame, five Celtic players have been selected, they are:

- Sir Kenny Dalglish MBE[246]

- Jimmy Johnstone[247]

- Jimmy McGrory[248]

- Billy McNeill MBE[249]

- Jock Stein CBE[250]

Honours

- record

- s shared record

Other honours

- European Cup/UEFA Champions League

- UEFA Cup/UEFA Europa League

- Intercontinental Cup

- British League Cup

- Winners: 1902[253]

- Empire Exhibition Trophy

- Winners: 1938[254]

- Coronation Cup

- Winners: 1953[255]

Other awards

- 1967[256]

- 1970[257]

- 20031[62]

- 20031[63]

- 20171[258]

1 Awarded to the fans of Celtic.

Quadruple

- League Title, Scottish Cup, League Cup, and European Cup: 1[259]

Trebles

- League Title, Scottish Cup, and League Cup: 8[260]

Doubles

- League Title and Scottish Cup: 13[259]

- League Title and League Cup: 7[259]

- Scottish Cup and Scottish League Cup: 1[259]

Records

Club records

- The Scottish Cup final win against Aberdeen in 1937 was attended by a crowd of 147,365 at Hampden Park in Glasgow, which remains a world record gate for a national cup final,[261] and also the highest attendance for a club football match in Europe.[262]

- Highest attendance for a European club competition match: 136,505 against Leeds United in the European Cup semi-final at Hampden Park (15 April 1970).[261]

- Record home attendance: 83,500 against Rangers on 1 January 1938.[nb 2][263][264][265][266] A 3–0 victory for Celtic.[267]

- UK record for an unbeaten run in domestic professional football: 69 games (60 won, 9 drawn), from 15 May 2016 until 17 December 2017 – a total of 582 days in all.[268]

- SPL record for an unbeaten run of home matches: 77 games, from 2001 to 2004.[269][270]

- 14 consecutive League Cup final appearances, from season 1964–65 to 1977–78 inclusive,[271] a world record for successive appearances in the final of a major football competition.[272]

- World record for total number of goals scored in a season (competitive games only): 196 (season 1966–67).[273]

- Most goals scored in one Scottish top-flight league match by one player: eight goals by Jimmy McGrory against Dunfermline in 9–0 win on 14 January 1928.[274]

- Highest score in a domestic British cup final: Celtic 7–1 Rangers (1957 Scottish League Cup Final).[275]

- Fastest hat-trick in European Club Football: Mark Burchill against Jeunesse Esch in 2000; 3 minutes (between twelfth minute and fifteenth minute), a record at the time.[266][276]

- Earliest Scottish Premiership title won: Won with eight games remaining in 2017, against Heart of Midlothian on 2 April 2017.[277]

- Biggest margin of victory in the SPL: 9–0 against Aberdeen, 6 November 2010.[278]

- Biggest margin of victory in the Scottish Premiership: 9–0 against Dundee United, 28 August 2022.

- Celtic and Hibernian hold the record for the largest transfer fee between two Scottish clubs (Scott Brown in May 2007).[279]

- Most expensive export from Scottish football: Kieran Tierney to Arsenal (August 2019).[280]

- First weekly football club publication in the UK: The Celtic View.[165]

- First European club to field a player from the Indian sub-continent: Mohammed Salim.[281]

- Gil Heron, who signed for Celtic in 1951, was the first black person to play professionally in Scotland;[282] his son Gil Scott-Heron rose to prominence in the 1970s as a hugely influential jazz and soul musician.[283]

Individual records

- Record appearances (all competitions): Billy McNeill, 822 from 1957 to 1975[284]

- Record appearances (League): Alec McNair, 583 from 1904 to 1925[285]

- Most capped player for Scotland: 102 (47 whilst at Celtic), Kenny Dalglish[286]

- Most international caps for Scotland while a Celtic player: 76, Paul McStay[287]

- Most caps won whilst at Celtic: 80, Pat Bonner[287]

- Record scorer: Jimmy McGrory, 522 (1922/23 – 1937/38)[284][288]

- Record scorer in league: Jimmy McGrory, 396[285]

- Most goals in a season (all competitions): Jimmy McGrory, 62 (1927/28) (47 in League, 15 in Cup competitions)[289]

- Most goals in a season (league only): Jimmy McGrory, 50[290] (1935/36)[291]

Club partners

As of 1 May 2024,[update] Celtic has partnerships with:[292]

|

Footnotes

- ^ Although the club was "formally constituted" in 1887, no matches were played until 1888. The latter date is listed by the club as their foundation date; for example, on the club badge.

- ^ Newspaper reports at the time indicate that the officially returned attendance was given as 83,500, with an estimated further 10,000 supporters locked out of the ground for safety reasons. However, the ground's capacity was gauged at the time as being around 88,000 and several subsequent sources (including the club's official website) have since revised the attendance up to 92,000.

References

- ^ Grove, Daryl (22 December 2014). "10 Soccer Things You Might Be Saying Incorrectly". PasteSoccer. Paste. Archived from the original on 30 July 2017. Retrieved 21 June 2017.

- ^ From Sporting Lisbon to Athletic Bilbao — why do we get foreign clubs' names wrong? Archived 7 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine, Michael Cox, The Athletic, 16 March 2023

- ^ Nardelli, Alberto (2 June 2015). "Which European football clubs have never been relegated?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 April 2024. Retrieved 7 April 2024.

Only two clubs have always played in Scotland's top division: Celtic (since 1890) and Aberdeen (since 1905).

- ^ Tudor, Stephen (6 October 2024). "Who Are The Most Successful Clubs In World Football?". 888sport. Retrieved 16 November 2024.

- ^ Association, Press (15 December 2003). "Celtic fans win Fifa award". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 15 November 2024.

- ^ "UEFA honour Celtic supporters with special Fair Play award". The Herald. 29 August 2003. Retrieved 15 November 2024.

- ^ Coogan, Tim Pat (2002). Wherever Green Is Worn: The Story of the Irish Diaspora. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 250. ISBN 978-1-4039-6014-6.

- ^ Wagg, Stephen (2002). British football and social exclusion. Routledge. p. 196. ISBN 978-0-7146-5217-7.

- ^ Wilson 1988, pp. 1–2

- ^ Campbell & Woods 1987, p. 23

- ^ Wilson 1988, p. 3

- ^ Thomas, Gareth (5 December 2014). "The Crest Dissected – Celtic FC". The Football History Boys. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f "Brief History". Celtic FC. Archived from the original on 10 May 2016. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ^ "The men who kicked it all off for the Celts". Celtic FC. Archived from the original on 28 May 2019. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r "Celtic – Kit History". Historical Football Kits. Archived from the original on 12 August 2011. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ Wilson 1988, p. 19

- ^ Cuddihy, Paul; Friel, David (July 2010). The Century Bhoys: The Official History of Celtic's Greatest Goalscorers. Black and White Publishing. ISBN 978-1845022976. Archived from the original on 9 September 2022. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- ^ "Scottish Premier League : Records". Statto. Archived from the original on 22 September 2013. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- ^ Wilson 1988, p. 29

- ^ Campbell & Woods 1987, pp. 53–54

- ^ Campbell & Woods 1987, pp. 78–79

- ^ Campbell & Woods 1987, p. 73

- ^ Brown, Alan. "Celtic FC's series of 62 matches unbeaten in Division One". The Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Archived from the original on 14 March 2013. Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- ^ "Jimmy McGrory (1904–1982)". World Football Legends. Archived from the original on 29 September 2015. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ^ "McGrory stands tall among game's giants". FIFA. 20 October 2010. Archived from the original on 23 October 2010. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ^ Campbell & Woods 1987, pp. 164–165

- ^ "Willie Maley". The Celtic Graves Society. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 17 September 2013.

- ^ Wilson 1988, p. 79

- ^ "Southern Football League 1940–1946". Scottish Football Historical Archive. Archived from the original on 28 May 2016. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ^ Rangers dominated wartime football but should their titles be recognised in the record books? Archived 1 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine, The Scotsman, 21 March 2020

- ^ "Football quiz: Celtic in Europe". The Guardian. 18 September 2009. Archived from the original on 6 March 2014. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- ^ Wilson 1988, p. 82

- ^ Wilson 1988, pp. 104–105

- ^ Wilson 1988, p. 105

- ^ "Post-war hat-tricks in competitive Old Firm games". The Scotsman. 11 September 2016. Archived from the original on 29 August 2018. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- ^ Wilson 1988, pp. 111–113

- ^ Campbell & Woods 1987, p. 207

- ^ Jacobs, Raymond (1 February 1965). "Mr Stein to become Celtic manager – New post for McGrory". The Glasgow Herald. Archived from the original on 15 February 2021. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ^ MacPherson, Archie (2007). Jock Stein: The Definitive Biography. Highdown. p. 119. ISBN 978-1-905156-37-5.

- ^ MacPherson, Archie (2007). Jock Stein: The Definitive Biography. Highdown. p. 152. ISBN 978-1-905156-37-5.

- ^ Wilson 1988, p. 134

- ^ "Celtic fight in final". The Times. 31 October 1966. Archived from the original on 3 October 2018. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

- ^ "Who has won a treble, including domestic league and cup titles, plus the European Cup or UEFA Champions League?". UEFA. 10 June 2023. Retrieved 14 June 2023.

- ^ Jensen, Neil Fredrik (1 June 2022). "Celtic 1967 – the only quadruple winners". Game of the People. Retrieved 14 June 2023.

- ^ "A Sporting Nation – Celtic win European Cup 1967". BBC Scotland. Archived from the original on 9 September 2022. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ "Celtic immersed in history before UEFA Cup final". Sports Illustrated. 20 May 2003. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- ^ Lennox, Doug (2009). Now You Know Soccer. Dundurn Press. p. 143. ISBN 978-1-55488-416-2.

now you know soccer who were the lisbon lions.

- ^ a b "Referee and both sides blamed for "war"". The Glasgow Herald. 6 November 1967. p. 6. Archived from the original on 9 September 2022. Retrieved 29 January 2015.

- ^ a b "Season 1969–70". European Cup History. Archived from the original on 18 August 2018. Retrieved 6 October 2013.

- ^ Reynolds, Jim. "Dalglish goal gives Celtic world record". The Glasgow Herald. No. 29 April 1974. p. 4. Archived from the original on 9 September 2022. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- ^ Wilson 1988, p. 189

- ^ "New Celtic team takes over. Three directors ousted as £17.8m rescue package pledged. The new team takes over with a promise". Herald Scotland. 5 March 1994. Archived from the original on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ^ Forsyth, Roddy (30 October 2009). "Celtic chairman John Reid pledges to keep the club's finances under control". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 23 July 2011.

- ^ "Celtic get by with a little help from their Scandinavians". BBC Sport. 9 May 1998. Archived from the original on 13 May 2008. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ "O'Neill confirmed as Celtic manager". The Guardian. 1 June 2000. Archived from the original on 31 December 2016. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ^ "O'Neill sees a brilliant new era for Celtic under Strachan". The Guardian. 26 May 2005. Archived from the original on 31 December 2016. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ^ "Celtic lift cup to complete Treble". BBC Sport. 26 May 2001. Archived from the original on 7 February 2006. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ "O'Neill vows to stay and savour Celtic in Europe". The Telegraph. 19 March 2001. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022.

- ^ a b "Celtic in Seville". Observer Sport Monthly. May 2003. Archived from the original on 13 March 2007. Retrieved 17 September 2006.

- ^ a b "Celtic 2–3 FC Porto". ESPN Soccernet. 21 May 2003. Archived from the original on 25 May 2011. Alt URL Archived 25 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Porto end Celtic's Uefa dream". BBC Sport. 21 May 2003. Archived from the original on 18 April 2012. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ a b c d "Celebrating Celtic pride in the heart of Andalusia". FIFA.com. 15 December 2003. Archived from the original on 4 July 2009.

- ^ a b c d "Celtic fans 'Europe's best'". BBC Sport. 28 August 2003. Archived from the original on 16 November 2005. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- ^ "Celtic 1 Heart Of Midlothian 0: Strachan's joy as Celtic are crowned champions". The Independent. 6 April 2006. Archived from the original on 21 October 2020. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ^ "Celtic 1–0 Man Utd". BBC Sport. 21 November 2006. Archived from the original on 10 September 2007. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ "Milan 1 Celtic 0: Inzaghi delight as Celtic defeat turns into celebration". Belfast Telegraph. 5 December 2007. Archived from the original on 29 November 2011. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ "Gordon Strachan stands down at Celtic". The Telegraph. 25 May 2009. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022.

- ^ "Tony Mowbray confirmed as new manager of Celtic". The Guardian. 16 June 2009. Archived from the original on 31 December 2016. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ^ "Lennon the way forward for Celtic". UEFA.com. 9 June 2010. Archived from the original on 2 January 2016. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ "Celtic hit nine past Aberdeen in record SPL victory". The Guardian. 6 November 2010. Archived from the original on 9 November 2010. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ^ Corrigan, Dermot (8 November 2012). "Barca stars praise Celtic atmosphere". ESPN News. Archived from the original on 7 February 2018. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- ^ Lamont, Alasdair (7 November 2012). "Celtic 2–1 Barcelona". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 12 November 2013.

- ^ Lamont, Alasdair (5 December 2012). "Celtic 2–1 Spartak Moscow". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 12 November 2013.

- ^ Lamont, Alasdair (26 May 2013). "Scottish Cup final: Hibernian 0–3 Celtic". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 14 January 2016. Retrieved 12 November 2013.

- ^ Campbell, Alan (26 March 2014). "Celtic crush Partick Thistle to make it three SPL titles in a row". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- ^ "Aberdeen 2–1 Celtic". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 26 February 2014. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- ^ McLaughlin, Chris (22 May 2014). "Neil Lennon ends his four-year spell as manager". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 22 May 2014. Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- ^ "Celtic confirm Ronny Deila as new manager". BBC Sport. 6 June 2014. Archived from the original on 6 June 2014. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- ^ "Ronny Deila appointed as new Celtic manager". Celtic FC. 6 June 2014. Archived from the original on 7 July 2014. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- ^ "Ronny Deila admits "disappointments" in announcing Celtic resignation". The National. 20 April 2016. Archived from the original on 16 June 2016. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- ^ a b Murray, Ewan (20 May 2016). "Celtic appoint Brendan Rodgers as manager to take over from Ronny Deila". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 20 May 2016. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- ^ Kane, Desmond (21 May 2016). "Brendan Rodgers finds his Paradise: Why Glasgow Celtic remain one of world's great clubs". Eurosport. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ^ "League Cup final: Aberdeen 0–3 Celtic as it happened". BBC Sport. 27 November 2016. Archived from the original on 29 November 2016. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ^ "Celtic's title triumph by numbers". BBC Sport. 2 April 2017. Archived from the original on 4 April 2017. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

- ^ Campbell, Andy (21 May 2017). "Celtic 2 – 0 Hearts". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 22 May 2017. Retrieved 22 May 2017.

- ^ "Celtic's unbeaten season: Records tumble for Scotland's 'invincibles'". BBC Sport. 21 May 2017. Archived from the original on 22 May 2017. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- ^ English, Tom (27 May 2016). "Celtic 2 – 1 Aberdeen". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 11 October 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- ^ "Celtic: Incredible feat to beat 100-year-old British record – Brendan Rodgers". BBC Sport. 4 November 2017. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- ^ McLauchlin, Brian (17 December 2017). "Heart of Midlothian 4–0 Celtic". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 29 April 2018. Retrieved 17 January 2018.

- ^ Murray, Ewan (26 November 2017). "Forrest and Dembélé seal Scottish League Cup for Celtic over Motherwell". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 27 November 2017. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- ^ Murray, Ewan (29 April 2018). "Celtic seal Scottish Premiership title with 5-0 rampage over Rangers". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 21 May 2018. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- ^ Forsyth, Roddy (19 May 2018). "Celtic claim unprecedented double treble with comfortable Scottish Cup final win over Motherwell". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- ^ "Brendan Rodgers: Leicester City appoint former Celtic boss as manager". BBC Sport. 26 February 2019. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- ^ "Heart of Midlothian 1–2 Celtic". BBC Sport. 25 May 2019. Archived from the original on 25 November 2020. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- ^ "Celtic appoint Neil Lennon as manager for second time". BBC Sport. 31 May 2019. Archived from the original on 31 May 2019. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ^ Forsyth, Roddy; Bagchi, Rob (8 December 2019). "Celtic make it 10 trophies in a row after magnificent Fraser Forster frustrates Rangers". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- ^ "Coronavirus in Scotland: Which Scottish events have been cancelled due to COVID-19?". Herald Scotland. 14 March 2020. Archived from the original on 1 May 2020. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- ^ McDermott, Scott (12 April 2020). "Celtic and Rangers title spat shows SPFL must consider the null and void elephant in the room". Daily Record. Archived from the original on 13 April 2020. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ^ "Celtic champions & Hearts relegated after SPFL ends season". BBC Sport. 18 May 2020. Archived from the original on 29 May 2021. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- ^ Lindsay, Clive (20 December 2020). "Celtic 3 - 3 Heart of Midlothian". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 19 December 2020. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- ^ "Neil Lennon: Celtic manager resigns with side 18 points adrift of Rangers". BBC Sport. 24 February 2021. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ^ "Rangers 2 - 0 Celtic". BBC Sport. 18 April 2021. Archived from the original on 8 May 2021. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ "Celtic unable to breach makeshift Hibs". BBC Sport. 15 May 2021. Archived from the original on 19 May 2021. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- ^ Wilson 1988, p. 5

- ^ "109 years in the hoops – 1903–2013". Not the View – Issue 208. 13 May 2012. pp. 14–15. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- ^ a b "Celtic badge". The Celtic Wiki. Archived from the original on 7 October 2015. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- ^ a b "Celtic". Tribal Colours. Archived from the original on 18 August 2013. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ^ Halliday, Stephen (9 January 2013). "Magners shirt cash for Celtic ends Old Firm double deals". The Scotsman. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ^ Halliday, Stephen (9 January 2013). "Magners shirt cash for Celtic ends Old Firm double deals". The Scotsman. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ^ "Celtic cross". When Saturday Comes. 9 July 2012. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ^ a b "92–93 part 1". NTV Celtic Fanzine. Archived from the original on 30 October 2013. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ^ Reynolds, Jim (16 June 1993). "McGinlay move: Hibs tell Celtic they must wait in the wings". Herald Scotland. Archived from the original on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ^ "New Balance's Celtic 2015/16 home kit launched". The Scotsman. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ "Introducing the New Celtic FC Lisbon Commemorative Kit Crest". Celtic FC. 3 May 2017. Archived from the original on 9 August 2017. Retrieved 25 July 2017.

- ^ "Celtic announce magnificent new five-year partnership with Adidas". Celtic FC. 13 March 2020. Archived from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- ^ "Celtic Football Club". Scottish Professional Football League. Archived from the original on 8 January 2014. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

- ^ Swan, Craig (11 November 2011). "Former Celtic star urges Old Firm to sell stadium names to save clubs". Daily Record. Archived from the original on 14 November 2011. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- ^ "Celtic". Scottish Football Ground Guide. Archived from the original on 11 March 2016. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- ^ "Celtic spirit shines on". FIFA.com. Archived from the original on 14 March 2013. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- ^ "The Birth of Celtic". Hibernian FC. 11 August 2009. Archived from the original on 21 January 2012. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Inglis 1996, p. 432

- ^ Inglis 1996, p. 435

- ^ Inglis 1996, p. 433

- ^ Inglis 1996, p. 434

- ^ "Scotland Home Record by Venue". London Hearts Supporters' Club. 2004. Archived from the original on 14 October 2011. Retrieved 12 November 2011.

- ^ "The first combined shinty/hurling match 1897". BBC – A Sporting Nation. November 2005. Archived from the original on 22 June 2012. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ "Bravery of fallen heroes". Celtic FC. 11 November 2011. Archived from the original on 12 October 2016. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- ^ Duncanson, Hilary (23 July 2014). "Queen tells of 'shared ideals' at Commonwealth Games opening ceremony". Irish Independent. Archived from the original on 23 May 2015. Retrieved 24 July 2014.

- ^ "Celtic become team ambassadors for Special Olympics". Celtic FC. 11 March 2013. Archived from the original on 29 January 2019. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- ^ Fulton, Rick (12 September 1997). "Caught Live". Daily Record. Archived from the original on 15 June 2013. Retrieved 12 November 2011.

- ^ "Celtic studying feasibility of standing area at Celtic Park". STV Sport. 23 September 2011. Archived from the original on 27 November 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ "Celtic secure green light for rail seating". Celtic FC. 9 June 2015. Archived from the original on 12 July 2016. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- ^ Stevens, Samuel (14 July 2016). "Celtic reveal new 2,600 capacity safe-standing area with Brendan Rodgers set for first home match as manager". The Independent. Archived from the original on 14 July 2016. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- ^ "Celtic reveal further details about £4m stadium investment as upgrades begin to take shape". Daily Record. 3 June 2018. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- ^ "Celtic to launch credit card for US fans". The Scotsman. 20 July 2003. Archived from the original on 15 March 2016. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- ^ The North American Federation of Celtic Supporters Clubs Archived 10 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine lists some 125 clubs and the Association of Irish Celtic Supporters Clubs 40 more

- ^ "Finalists relishing Hampden visit". BBC Sport. 4 May 2007. Archived from the original on 30 August 2007. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- ^ "Celtic fans get Fifa award". BBC Sport. 12 December 2003. Archived from the original on 18 May 2008. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

- ^ "SPL 2010/2011 Stats – average home attendance". Football-Lineups. Archived from the original on 9 September 2022. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

- ^ "Top thirty football clubs in Europe ranked by attendances". Football Economy. Archived from the original on 29 January 2016. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

- ^ "Celtic & Rangers among top 20 most watched clubs". BBC Sport. 16 April 2019. Archived from the original on 16 April 2019. Retrieved 17 April 2019.

- ^ "Top 10 : les meilleurs publics du monde". So Foot. 21 October 2013. Archived from the original on 15 March 2014. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- ^ Forbes, Craig (23 October 2017). "Celtic win FIFA's 'Best Fans of the Year' award". The Scotsman. Archived from the original on 12 December 2017. Retrieved 11 December 2017.

- ^ a b "Rivalries: Celtic vs Rangers. Old Firm's enduring appeal". FIFA. Archived from the original on 30 June 2013. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ McNab, Ken (11 March 2017). "Why Old Firm match is greatest derby in the world". Evening Times. Archived from the original on 2 July 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- ^ "Classic Rivalries: Old Firm's enduring appeal". FIFA. 16 April 2016. Archived from the original on 26 March 2018. Retrieved 16 December 2018.

- ^ Ross, James. "Scotland – List of Champions – Summary". The Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Archived from the original on 22 September 2008. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- ^ "Premier League 2014/2015 » Attendance » Home matches". worldfootball.net. Archived from the original on 18 June 2018. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- ^ "Premiership 2014/2015 » Attendance » Home matches". worldfootball.net. Archived from the original on 1 April 2017. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- ^ a b Wilson, Richard (2012). Inside the Divide. Canongate Books. p. 87."What is being asserted is two identities: Rangers and Celtic. There are other boundaries: Protestant and Catholic / Unionist and Republican / Conservative and Socialist...."

- ^ a b "History of Sectarianism". Nil by Mouth. 2010. Archived from the original on 9 September 2022. Retrieved 27 January 2011.

- ^ "Celtic head-to-head v Rangers". Soccerbase. Archived from the original on 28 February 2017. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- ^ a b Millen, Dianne (April 2004). "Firm Favourites: Old Firm". When Saturday Comes. Archived from the original on 24 May 2012. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- ^ Foer, Franklin (2010). How Soccer Explains the World: An Unlikely Theory of Globalization (Reprint ed.). Harper Perennial. pp. 36–37. ISBN 978-0061978050.

- ^ McCarra, Kevin (18 May 2009). "Firm enemies – Rangers and Celtic, 1909–2009". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 23 June 2014. Retrieved 28 January 2010.

- ^ "Rangers make history out of chaos". BBC News. 3 May 1999. Archived from the original on 27 March 2012. Retrieved 16 August 2010.

- ^ "Bigotry puzzle for Old Firm". BBC News. 11 October 2001. Archived from the original on 13 March 2007. Retrieved 6 April 2006.

- ^ "Celtic seek end to 'IRA chants'". BBC News. 17 September 2002. Archived from the original on 18 July 2004. Retrieved 25 October 2010.

- ^ "Celtic fans boo the Queen Mum; Title win marred by jeers during silence". Sunday Mirror. 7 April 2002. Archived from the original on 9 September 2022. Retrieved 25 October 2010.

- ^ "Poppy demo fans face a Celtic ban". Evening Times. 9 November 2010. Archived from the original on 1 August 2012.

- ^ a b "Celtic plan ban for anti-poppy protesters". BBC Sport. 8 November 2010. Archived from the original on 9 September 2022. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- ^ "Celtic accept UEFA fine for fans' pro-IRA chants". 13 December 2011. Archived from the original on 3 October 2021. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ^ "Celtic View celebrates 50 years: Pictorial tribute to world's first and longest running official club newspaper". Daily Record. 11 August 2015. Archived from the original on 7 May 2018. Retrieved 7 May 2018.

- ^ a b Campbell, Tom; Potter, David (7 October 1999). Jock Stein: The Celtic Years. Mainstream Publishing. ISBN 1-84018-2415. Archived from the original on 13 May 2022. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- ^ Quinn, John (October 1994). Jungle Tales: Celtic Memories of an Epic Stand (1st ed.). Mainstream Sport. ISBN 978-1851586738. Archived from the original on 13 May 2022. Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- ^ "Celtic View temporarily closed as Covid-19 affects in-house press". 67 Hail Hail. 20 January 2021. Archived from the original on 20 August 2021. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ^ Davidson, Euan (19 August 2021). "Club announce return of beloved Celtic View magazine, with some key changes". 67 Hail Hail. Archived from the original on 20 August 2021. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ^ "Celtic TV shut down confirmed". Digital Spy. Hachette Filipacchi UK. 24 June 2009. Archived from the original on 24 May 2011. Retrieved 24 January 2011.

- ^ "Channel 67 has become Celtic TV". Channel 67. Celtic FC. Archived from the original on 7 August 2009.

- ^ "Shop :: Celtic TV". Celtic FC. Archived from the original on 18 March 2017. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- ^ "Belfast Celtic F.C. – Souvenir History 1891–1939 – published 1939 – (unknown author) (unknown publisher)". Belfast Celtic – The Grand Old Team. Archived from the original on 28 November 2014. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ^ "Belfast Celtic". Groundtastic. Archived from the original on 28 August 2008. Retrieved 11 February 2009.

- ^ "The History of the Grand Old Team". Belfast Celtic – The Grand Old Team. Archived from the original on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- ^ "NIFL Premier Intermediate". Northern Ireland Football League. Archived from the original on 5 January 2017. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- ^ a b "Donegal Celtic FC". Napit.co.uk Sports Information & News. Archived from the original on 23 October 2015. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- ^ Bairner, Alan, ed. (2005). Sport and the Irish. University College Dublin Press. ISBN 978-1-910820-93-3. Archived from the original on 9 September 2022. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- ^ "Annual Anti-Racism World Cup about to get underway". The Irish News. 4 August 2015. Archived from the original on 28 February 2017. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- ^ "Lurgan Celtic". Lower League Manager. Archived from the original on 14 June 2018. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- ^ "NIFL Championship". Northern Ireland Football League. Archived from the original on 5 January 2017. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- ^ "Club Mark awarded to Tuam Celtic". FAI. 9 July 2021. Archived from the original on 21 December 2021. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- ^ "Castlebar Celtic F.C. – Club History". www.castlebarceltic.com. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ^ paulveverka (9 August 2014). "Blantyre Celtic Football Club/". Blantyre Project - Official History Archives, Lanarkshire. Archived from the original on 30 September 2019. Retrieved 6 December 2019.

- ^ "History". Cleator Moor Celtic FC. Archived from the original on 5 January 2017. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- ^ Purden, Richard (27 March 2014). "Celtic Nation: A team on the rise". The Irish Post. Archived from the original on 5 January 2017. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- ^ Coney, Steven (28 April 2015). "Cash-strapped Celtic Nation to fold as dream turns sour". The Non-League Paper. Archived from the original on 28 February 2017. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- ^ "Depleted Celtic grind out impressive Birtley win". West Allotment Celtic. 14 October 2013. Archived from the original on 5 January 2017. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- ^ "Yeovil are Hoop-ing for glory". The Mirror. 3 June 2003. Archived from the original on 25 March 2017. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- ^ "Celtic Sold To New Owner?". Soccer Laduma. 21 July 2014. Archived from the original on 21 January 2022. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ^ "Soccer: Celtic FC America looks to find permanent home in League City". Chron.com. 9 July 2019. Archived from the original on 23 October 2020. Retrieved 18 August 2020.