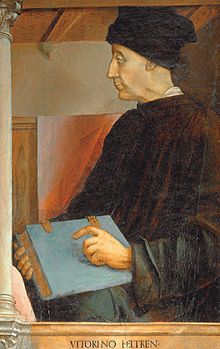

Vittorino da Feltre

Vittorino da Feltre (1378 – February 2, 1446) was an Italian humanist and teacher. He was born in Feltre, Belluno, Republic of Venice and died in Mantua. His real name was Vittorino Rambaldoni. It was in Vittorino that the Renaissance idea of the complete man, or l'uomo universale — health of body, strength of character, wealth of mind — reached its first formulation.[1]

Biography

[edit]He studied under John of Ravenna[2] and at Padua under Gasparino da Barzizza. He later taught there, but after a few years he was invited by Gianfrancesco I Gonzaga, the marquis of Mantua, to educate his children. At Mantua, Vittorino set up a school at which he taught the marquis's children and the children of other prominent families — both sons and daughters[3] — together with many poor children whom he charged no fee, treating them all on an equal footing. He not only taught the humanistic subjects, but placed special emphasis on religious and physical education. Vittorino’s lessons in Greek and Latin, mathematics, music, art, religion, history, poetry and philosophy were so enjoyable that his school was known as La Casa Gioiosa, “The House of Joy”. It soon became famous all over Italy, and noble children from other cities came to Mantua to study with Vittorino. In fact, so many young nobles were educated at La Casa Gioiosa that it also came to be called the School of Princes.

He was one of the first modern educators to develop during the Renaissance. Many of his methods were novel, particularly in the close contacts between teacher and pupil as he had with Gasparino da Barzizza and in the adaptation of the teaching to the ability and needs of the child. He lived with students and befriended them in the first secular boarding school.[4] Vittorino's school was well lit and built of better construction than other schools of the time. Vittorino also made school work more interesting, adding field trips to his curricula. He watched the health of his students very carefully, and generally elevated the status of teachers. Schools throughout Europe (especially England) copied Vittorino's model. Many of fifteenth century Italy's greatest scholars, including Guarino da Verona, Poggio Bracciolini, and Francesco Filelfo, sent their sons to study under Vittorino da Feltre. Vittorino's other students included Federigo da Montefeltro and Gregorio Correr. Theodorus Gaza improved his studies in Latin and was a scholar especially for Greek. After Vittorino's death, Iacopo da San Cassiano took over direction of the school.[5]

See also

[edit]- Feltre School – a school embodying Vittorino da Feltre's principles in Chicago, Illinois

Notes

[edit]- ^ Durant, Will (1953). The Renaissance. The Story of Civilization. Vol. 5. New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 250.

- ^ . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 15 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 449.

- ^ Durant, Will (1953). The Renaissance. New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 249.

- ^ Cole, Luella (1962). A History of Education: Socrates to Montessori. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

- ^ Paolo d'Alessandro e Pier Daniele Napolitani, Archimede Latino. Iacopo da San Cassiano e il corpus archimedeo alla metà del Quattrocento, Paris, Les Belles Lettres, 2012

Further reading

[edit]- Vittorino da Feltre at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- McCormick, P.J. (1906). "Two Catholic Mediæval Educators: I. Vittorino da Feltre," The Catholic University Bulletin 12, pp. 453–484.