Noasauridae

| Noasaurids | |

|---|---|

| |

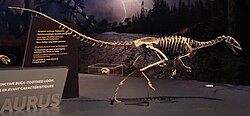

| Reconstructed skeleton of Masiakasaurus knopfleri, Royal Ontario Museum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Clade: | †Abelisauria |

| Family: | †Noasauridae Bonaparte & Powell, 1980 |

| Subgroups | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Noasauridae is an extinct family of theropod dinosaurs belonging to the group Ceratosauria. They were closely related to the short-armed abelisaurids, although most noasaurids had much more traditional body types generally similar to other theropods. Their heads, on the other hand, had unusual adaptations depending on the subfamily. 'Traditional' noasaurids, sometimes grouped in the subfamily Noasaurinae, had sharp teeth which splayed outwards from a downturned lower jaw.

The most complete and well-known example of these kinds of noasaurids was Masiakasaurus knopfleri from Madagascar.[4] Another group, Elaphrosaurinae, has also been placed within Noasauridae by some studies.[3] Elaphrosaurines developed toothless jaws and herbivorous diets, at least as adults.[5]

The most complete and well known elaphrosaurine was Limusaurus inextricabilis. At least some noasaurids had pneumatised cervical vertebrae.[6] Some are considered to have had cursorial habits.[7] Noasauridae is defined as all theropods closer to Noasaurus than to Abelisaurus.[8]

Description

[edit]Noasauridae was a very diverse group, with the two most complete members, Masiakasaurus and Limusaurus, showing unusual features very different from each other. Masiakasaurus had an unusually downturned jaw, with long and sharply pointed spoon-shaped teeth. Some of these teeth were nearly horizontal in orientation. Limusaurus, on the other hand, was completely toothless as an adult and likely possessed a horny beak. This large disparity means that it is difficult to find any skull features shared by members of Noasauridae as a whole.

Noasaurids had longer arms than their relatives the abelisaurids, whose arms were tiny and diminished. Although by no means as large or specialized as the arms of advanced bird-like theropods, noasaurid arms were nevertheless capable of movement and use, possibly even for hunting in large-clawed genera such as Noasaurus. Some genera such as Limusaurus did have somewhat reduced arms and hands, but far from the extent that abelisaurids acquired. Noasaurids were also nimble and lightly built, with feet showing adaptations for running such as a long central foot bone (metatarsal III). Noasaurids varied in size, from the small Velocisaurus which was under 5 feet (1.5 meters) long, to much larger genera such as Elaphrosaurus and Deltadromeus, which were more than 20 feet (6.1 meters) in length.[3]

A collection of features which characterize noasaurids in particular has been compiled by Rauhut & Carrano (2016), who included controversial taxa such as Deltadromeus and the elaphrosaurines within Noasauridae. If these groups did not belong to Noasauridae as the study claims, then these similarities are examples of convergent evolution. Among the most prominent traits relate to the shoulder region. In this family, the long, upward-stretching scapula (shoulder blade) merges with the smaller and more compact coracoid (shoulder girdle), forming a fused shoulder bone known as a scapulocoracoid. While the presence of a scapulocoracoid is by no means unique to this family, noasaurids do have particularly large and wide scapulocoracoids, with a tall and semicircular coracoid region. The hooked rear edge of the coracoid region is also offset from the glenoid (shoulder socket) by a large U-shaped notch. The humerus (upper arm bone) was thin and straight, with a low and somewhat rounded humeral head (the portion which attached to the shoulder). In contrast, abelisaurids had a large and bulbous humeral head (although similarly rounded) while that of other theropods was flattened from front to back.[3]

The leg is also somewhat characteristic in members of this family. The tibia (large innermost bone of the lower leg) was flattened from the front near the foot, although it was rounded further up the leg. As in other theropods, the femur (thigh bone) of a noasaurid had a ridge along the inner rear surface, known as a fourth trochanter. However, in noasaurines and elaphrosaurines (but not necessarily other genera such as Deltadromeus), this fourth trochanter was much smaller and lower than the enlarged crest-like structure present in the majority of basal theropods;[3] only a few other groups of theropods (coelophysoids, coelurosaurs, and a few species of abelisaurids) also have reduced fourth trochanters.[8] In addition, the two subfamilies have a metatarsal II (the foot bone connected to the innermost major toe) which was flattened from the side. Further reductions to this metatarsal were present in noasaurines (particularly Velocisaurus).[7] In these genera as well as Deltadromeus, metatarsal IV (which connected to the outermost major toe) also became reduced in some respects.[8]

In all noasaurids, the mid caudals (vertebrae in the middle of the tail) had very low neural spines. The cervical (neck) vertebrae, on the other hand, were quite varied within this family. In noasaurines and a few other genera (such as Laevisuchus), the neural spines of vertebrae at the front of the neck were positioned towards the front part of their respective vertebrae. This is quite unusual compared to other theropods, which have neural spines roughly midway down their vertebrae. These genera also have long and spine-like epipophyses on the cervicals of most of the neck, although they diminish near the neck.[6] Epipophyses are bony projections located above the postzygapophyses (joints on the rear edge of a vertebra connecting to the front edge of the following vertebra). Elaphrosaurines, on the other hand, have cervical epipophyses which are much more diminished or even absent in the case of Elaphrosaurus.[3] Many noasaurids are only known from vertebrae, including both valid (Laevisuchus, Spinostropheus) and dubious (Composuchus, Jubbulpuria, Ornithomimoides, Coeluroides) genera.[8]

Noasaurinae

[edit]

Noasaurines are Late Cretaceous noasaurids known exclusively from southern continents and islands such as South America, Madagascar, and India (which was an island near Madagascar during the Cretaceous). In 2020 indeterminate remains were described from the Barremian-Aptian and Cenomanian of Australia.[9] Members of this subfamily are definitively part of Noasauridae, although this group may not necessarily be elevated to subfamily status whenever elaphrosaurines are found to be outside of Noasauridae. Many members of this subfamily are quite fragmentary, and as a result the appearance and biology of the average noasaurine must be inferred from the most complete member of the group, Masiakasaurus. Rauhut & Carrano (2016) define Noasaurinae as "all noasaurids more closely related to Noasaurus than to Elaphrosaurus, Abelisaurus, Ceratosaurus, or Allosaurus".[3]

Masiakasaurus (and presumably other noasaurines) had a downturned lower jaw with long teeth splaying forwards. These teeth were spoon-shaped with sharply pointed tips and serrations along their outer edge. The rest of the teeth in the mouth were similar to the teeth of more conventional theropods. The rest of the body was also more similar to that of conventional theropods, with a neck, arms, and legs of moderate length. At least one noasaurine, the eponymous Noasaurus, had a large and deeply curved "sickle-shaped" claw of the hand. The diet of noasaurines is difficult to determine, with hypotheses ranging from fish to insects or other small animals.

Rauhut & Carrano (2016) found only a single unambiguous trait used to diagnose noasaurines to the exception of other noasaurids. That trait is the fact that their metatarsal II has a diminished proximal (near) end.[3] One noasaurine, Velocisaurus, took this trait even further, with both its metatarsal II and IV reduced to very thin rod-like bones along their entire length.[7]

Elaphrosaurinae

[edit]

It is not entirely certain if elaphrosaurines are legitimate examples of noasaurids. Both Limusaurus and Elaphrosaurus have been considered basal ceratosaurians by many studies, with most of these studies considering them even more primitive than Ceratosaurus.[8][10] The most well-known elaphrosaurines lived during the Jurassic period, much older than the Late Cretaceous period noasaurines. Nevertheless, the existence of Eoabelisaurus shows that abelisauroids had evolved by the Jurassic period, and Cretaceous elaphrosaurines such as Huinculsaurus have been discovered. It would make sense for Noasauridae (the sister taxa to Abelisauridae) to have evolved during the Jurassic, meaning that the early appearance of elaphrosaurines would not preclude a within Noasauridae. In 2016, a redescription of Elaphrosaurus by Oliver Rauhut and Matthew Carrano argued against earlier hypotheses that elaphrosaurines were basal ceratosaurs, instead placing them alongside noasaurines within a monophyletic Noasauridae. This study formally defined Elaphrosaurinae as "all noasaurids more closely related to Elaphrosaurus than to Noasaurus, Abelisaurus, Ceratosaurus, or Allosaurus".[3]

Generally speaking, elaphrosaurines were lightly built theropods, with small skulls and long necks and legs. If Limusaurus is any indication, adult elaphrosaurines were completely toothless, and their mouths were probably edged with a horny beak. It is likely that Limusaurus and other elaphrosaurines were primarily herbivorous as adults, due to mature Limusaurus specimens preserving gastroliths and chemical signatures resembling those of herbivorous dinosaurs. However, juvenile Limusaurus specimens retained teeth and lacked these signs of herbivory, meaning that young elaphrosaurines may have been more capable of a carnivorous or omnivorous diet.[5] The largest known noasaurid, Elaphrosaurus, is the namesake of Elaphrosaurinae. Members of this genus could grow up to 20 feet (6.1 meters) long, although they were significantly lighter than similarly sized carnivorous contemporaries such as Ceratosaurus.

Rauhut & Carrano (2016) listed several features which could be used to diagnose Elaphrosaurinae. Elaphrosaurine cervical vertebrae are amphicoelous, meaning that both their front and rear faces are concave, particularly the front face which is quite strongly concave. While strongly concave front faces are common among many archosaurs, they are quite rare in all but the most basal theropods. Carnosaurs, megalosauroids, coelurosaurs, and most other ceratosaurians (including noasaurines) all have vertebrae which have front faces ranging from very weakly concave to flat (platycoelous) or convex (opisthocoelous). Another notable feature of elaphrosaurine cervical vertebrae is that their cervical ribs are completely fused to the centrum (main body) of their corresponding vertebrae.[3]

Elaphrosaurines also have several diagnostic hip features. The hip is quite small compared to their long legs. The femur (thigh bone) is more than 1.3 times the length of the ilium (upper plate-like bone of the hip) in members of this subfamily, while most other ceratosaurians have shorter legs and a femur approximately the same length of the ilium. The connection between the ilium and the pubis (forward-projecting rod-like lower bone of the hip) is also more simple than in other ceratosaurians. While other ceratosaurians have a peg-and-socket connection between the two bones, elaphrosaurines simply have a flat contact between the two.[3]

In 2020 a middle cervical vertebra from the lower Albian Eumeralla Formation of Cape Otway, Victoria, Australia was referred to Elaphrosaurinae. This is the first evidence of Elaphrosaurinae from Australia.[11][12]

Classification

[edit]The following cladogram is based on the phylogenetic analysis conducted by Rauhut and Carrano in 2016, showing the relationships among the Noasauridae:[3]

| Abelisauroidea |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Even in recent studies, the composition of Noasauridae has been difficult to resolve. An analysis conducted by Tortosa et al. (2013)[10] recovered Dahalokely as a basal noasaurid.[10] However, another analysis later that year found it to be a basal carnotaurine instead.[3] Similarly, the genus Genusaurus has been found to be a noasaurid by some older studies, but other studies have classified it as an abelisaurid.[13][3] Deltadromeus is a particularly controversial genus, as it shares many features with noasaurids but is also very similar to Gualicho, which has been classified as a close relative of the enigmatic (but generally considered non-ceratosaurian) megaraptorans.[14] A 2017 study describing ontogenetic changes in Limusaurus and the effect of juvenile taxa on phylogenetic analyses provided various phylogenetic trees which varied based on which Limusaurus specimens were used. The structure of Noasauridae changed greatly depending on the age of the Limusaurus specimens, although Genusaurus and Deltadromeus were resolved as noasaurids in each diagnosis.[5]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Cerroni, M.A.; Agnolin, F.L.; Brissón Egli, F.; Novas, F.E. (2019). "The phylogenetic position of Afromimus tenerensis Sereno, 2017 and its paleobiogeographical implications". Journal of African Earth Sciences. 159: 103572. doi:10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2019.103572. S2CID 201352476.

- ^ Averianov, A. O.; Skutschas, P. P.; Atuchin, A. A.; Slobodin, D. A.; Feofanova, O. A.; Vladimirova, O. N. (2024). "The last ceratosaur of Asia: a new noasaurid from the Early Cretaceous Great Siberian Refugium". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 291 (2023). 20240537. doi:10.1098/rspb.2024.0537.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Rauhut, Oliver W. M.; Carrano, Matthew T. (2016-04-22). "The theropod dinosaur Elaphrosaurus bambergi Janensch, 1920, from the Late Jurassic of Tendaguru, Tanzania". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 178 (3): 546–610. doi:10.1111/zoj.12425. ISSN 0024-4082.

- ^ Andrew H. Lee & Patrick M. O’Connor (2013) Bone histology confirms determinate growth and small body size in the noasaurid theropod Masiakasaurus knopfleri. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 33(4): 865-876

- ^ a b c Wang, S.; Stiegler, J.; Amiot, R.; Wang, X.; Du, G.-H.; Clark, J.M.; Xu, X. (2017). "Extreme Ontogenetic Changes in a Ceratosaurian Theropod" (PDF). Current Biology. 27 (1): 144–148. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.10.043. PMID 28017609. S2CID 441498.

- ^ a b Arthur Souza Brum, Elaine Batista Machado, Diogenes de Almeida Campos & Alexander Wilhelm Armin Kellner (2017). Description of uncommon pneumatic structures of a noasaurid (Theropoda, Dinosauria) cervical vertebra to the Bauru Group (Upper Cretaceous), Brazil. Cretaceous Research (advance online publication). doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cretres.2017.10.012

- ^ a b c Egli, F. B.; AgnolÍn, F. L.; Novas, Fernando (2016). "A new specimen of Velocisaurus unicus (Theropoda, Abelisauroidea) from the Paso Córdoba locality (Santonian), Río Negro, Argentina". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 36 (4): e1119156. doi:10.1080/02724634.2016.1119156. hdl:11336/46726. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 87699625.

- ^ a b c d e Carrano, Matthew T.; Sampson, Scott D. (2008-01-01). "The Phylogeny of Ceratosauria (Dinosauria: Theropoda)" (PDF). Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 6 (2): 183–236. doi:10.1017/S1477201907002246. ISSN 1477-2019. S2CID 30068953. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-05-22.

- ^ Brougham, Tom; Smith, Elizabeth T.; Bell, Phil R. (January 2020). "Noasaurids are a component of the Australian 'mid'-Cretaceous theropod fauna". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 1428. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-57667-7. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6989633. PMID 31996712.

- ^ a b c Tortosa, Thierry; Eric Buffetaut; Nicolas Vialle; Yves Dutour; Eric Turini; Gilles Cheylan (2013). "A new abelisaurid dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of southern France: Palaeobiogeographical implications". Annales de Paléontologie. 100 (1): 63–86. doi:10.1016/j.annpal.2013.10.003.

- ^ Poropat, Stephen F.; Pentland, Adele H.; Duncan, Ruairidh J. (May 2020). "First elaphrosaurine theropod dinosaur (Ceratosauria: Noasauridae) from Australia — A cervical vertebra from the Early Cretaceous of Victoria". Gondwana Research. 84: 284–295. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2020.03.009. S2CID 218930877.

- ^ Poropat, Stephen F.; Pentland, Adele H.; Duncan, Ruairidh J.; Bevitt, Joseph J.; Vickers-Rich, Patricia; Rich, Thomas H. (2020-08-01). "First elaphrosaurine theropod dinosaur (Ceratosauria: Noasauridae) from Australia — A cervical vertebra from the Early Cretaceous of Victoria". Gondwana Research. 84: 284–295. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2020.03.009. ISSN 1342-937X. S2CID 218930877.

- ^ Leonardo S. Filippi; Ariel H. Méndez; Rubén D. Juárez Valieri; Alberto C. Garrido (2016). "A new brachyrostran with hypertrophied axial structures reveals an unexpected radiation of latest Cretaceous abelisaurids". Cretaceous Research. 61: 209–219. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2015.12.018. hdl:11336/149906.

- ^ Apesteguía, Sebastián; Smith, Nathan D.; Juárez Valieri, Rubén; Makovicky, Peter J. (2016-07-13). "An Unusual New Theropod with a Didactyl Manus from the Upper Cretaceous of Patagonia, Argentina". PLOS ONE. 11 (7): e0157793. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1157793A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0157793. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4943716. PMID 27410683.