Covariance and contravariance (computer science)

| Type systems |

|---|

| General concepts |

| Major categories |

|

| Minor categories |

Many programming language type systems support subtyping. For instance, if the type Cat is a subtype of Animal, then an expression of type Cat should be substitutable wherever an expression of type Animal is used.

Variance is how subtyping between more complex types relates to subtyping between their components. For example, how should a list of Cats relate to a list of Animals? Or how should a function that returns Cat relate to a function that returns Animal?

Depending on the variance of the type constructor, the subtyping relation of the simple types may be either preserved, reversed, or ignored for the respective complex types. In the OCaml programming language, for example, "list of Cat" is a subtype of "list of Animal" because the list type constructor is covariant. This means that the subtyping relation of the simple types is preserved for the complex types.

On the other hand, "function from Animal to String" is a subtype of "function from Cat to String" because the function type constructor is contravariant in the parameter type. Here, the subtyping relation of the simple types is reversed for the complex types.

A programming language designer will consider variance when devising typing rules for language features such as arrays, inheritance, and generic datatypes. By making type constructors covariant or contravariant instead of invariant, more programs will be accepted as well-typed. On the other hand, programmers often find contravariance unintuitive, and accurately tracking variance to avoid runtime type errors can lead to complex typing rules.

In order to keep the type system simple and allow useful programs, a language may treat a type constructor as invariant even if it would be safe to consider it variant, or treat it as covariant even though that could violate type safety.

Formal definition

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2021) |

Suppose A and B are types, and I<U> denotes application of a type constructor I with type argument U.

Within the type system of a programming language, a typing rule for a type constructor I is:

- covariant if it preserves the ordering of types (≤), which orders types from more specific to more generic: If

A ≤ B, thenI<A> ≤ I<B>; - contravariant if it reverses this ordering: If

A ≤ B, thenI<B> ≤ I<A>; - bivariant if both of these apply (i.e., if

A ≤ B, thenI<A> ≡ I<B>);[1] - variant if covariant, contravariant or bivariant;

- invariant or nonvariant if not variant.

The article considers how this applies to some common type constructors.

C# examples

[edit]For example, in C#, if Cat is a subtype of Animal, then:

IEnumerable<Cat>is a subtype ofIEnumerable<Animal>. The subtyping is preserved becauseIEnumerable<T>is covariant onT.Action<Animal>is a subtype ofAction<Cat>. The subtyping is reversed becauseAction<T>is contravariant onT.- Neither

IList<Cat>norIList<Animal>is a subtype of the other, becauseIList<T>is invariant onT.

The variance of a C# generic interface is declared by placing the out (covariant) or in (contravariant) attribute on (zero or more of) its type parameters.[2]: 144 The above interfaces are declared as IEnumerable<out T>, Action<in T>, and IList<T>. Types with more than one type parameter may specify different variances on each type parameter. For example, the delegate type Func<in T, out TResult> represents a function with a contravariant input parameter of type T and a covariant return value of type TResult.[3][2]: 145 The compiler checks that all types are defined and used consistently with their annotations, and otherwise signals a compilation error.

The typing rules for interface variance ensure type safety. For example, an Action<T> represents a first-class function expecting an argument of type T,[2]: 144 and a function that can handle any type of animal can always be used instead of one that can only handle cats.

Arrays

[edit]Read-only data types (sources) can be covariant; write-only data types (sinks) can be contravariant. Mutable data types which act as both sources and sinks should be invariant. To illustrate this general phenomenon, consider the array type. For the type Animal we can make the type Animal[], which is an "array of animals". For the purposes of this example, this array supports both reading and writing elements.

We have the option to treat this as either:

- covariant: a

Cat[]is anAnimal[]; - contravariant: an

Animal[]is aCat[]; - invariant: an

Animal[]is not aCat[]and aCat[]is not anAnimal[].

If we wish to avoid type errors, then only the third choice is safe. Clearly, not every Animal[] can be treated as if it were a Cat[], since a client reading from the array will expect a Cat, but an Animal[] may contain e.g. a Dog. So the contravariant rule is not safe.

Conversely, a Cat[] cannot be treated as an Animal[]. It should always be possible to put a Dog into an Animal[]. With covariant arrays this cannot be guaranteed to be safe, since the backing store might actually be an array of cats. So the covariant rule is also not safe—the array constructor should be invariant. Note that this is only an issue for mutable arrays; the covariant rule is safe for immutable (read-only) arrays.

Likewise, the contravariant rule would be safe for write-only arrays.

Covariant arrays in Java and C#

[edit]Early versions of Java and C# did not include generics, also termed parametric polymorphism. In such a setting, making arrays invariant rules out useful polymorphic programs.

For example, consider writing a function to shuffle an array, or a function that tests two arrays for equality using the Object.equals method on the elements. The implementation does not depend on the exact type of element stored in the array, so it should be possible to write a single function that works on all types of arrays. It is easy to implement functions of type:

boolean equalArrays(Object[] a1, Object[] a2);

void shuffleArray(Object[] a);

However, if array types were treated as invariant, it would only be possible to call these functions on an array of exactly the type Object[]. One could not, for example, shuffle an array of strings.

Therefore, both Java and C# treat array types covariantly.

For instance, in Java String[] is a subtype of Object[], and in C# string[] is a subtype of object[].

As discussed above, covariant arrays lead to problems with writes into the array. Java[4]: 126 and C# deal with this by marking each array object with a type when it is created. Each time a value is stored into an array, the execution environment will check that the run-time type of the value is equal to the run-time type of the array. If there is a mismatch, an ArrayStoreException (Java)[4]: 126 or ArrayTypeMismatchException (C#) is thrown:

// a is a single-element array of String

String[] a = new String[1];

// b is an array of Object

Object[] b = a;

// Assign an Integer to b. This would be possible if b really were

// an array of Object, but since it really is an array of String,

// we will get a java.lang.ArrayStoreException.

b[0] = 1;

In the above example, one can read from the array (b) safely. It is only trying to write to the array that can lead to trouble.

One drawback to this approach is that it leaves the possibility of a run-time error that a stricter type system could have caught at compile-time. Also, it hurts performance because each write into an array requires an additional run-time check.

With the addition of generics, Java[4]: 126–129 and C# now offer ways to write this kind of polymorphic function without relying on covariance. The array comparison and shuffling functions can be given the parameterized types

<T> boolean equalArrays(T[] a1, T[] a2);

<T> void shuffleArray(T[] a);

Alternatively, to enforce that a C# method accesses a collection in a read-only way, one can use the interface IEnumerable<object> instead of passing it an array object[].

Function types

[edit]Languages with first-class functions have function types like "a function expecting a Cat and returning an Animal" (written cat -> animal in OCaml syntax or Func<Cat,Animal> in C# syntax).

Those languages also need to specify when one function type is a subtype of another—that is, when it is safe to use a function of one type in a context that expects a function of a different type.

It is safe to substitute a function f for a function g if f accepts a more general type of argument and returns a more specific type than g. For example, functions of type animal -> cat, cat -> cat, and animal -> animal can be used wherever a cat -> animal was expected. (One can compare this to the robustness principle of communication: "be liberal in what you accept and conservative in what you produce.") The general rule is:

- if and .

Using inference rule notation the same rule can be written as:

In other words, the → type constructor is contravariant in the parameter (input) type and covariant in the return (output) type. This rule was first stated formally by John C. Reynolds,[5] and further popularized in a paper by Luca Cardelli.[6]

When dealing with functions that take functions as arguments, this rule can be applied several times. For example, by applying the rule twice, we see that if . In other words, the type is covariant in the position of . For complicated types it can be confusing to mentally trace why a given type specialization is or isn't type-safe, but it is easy to calculate which positions are co- and contravariant: a position is covariant if it is on the left side of an even number of arrows applying to it.

Inheritance in object-oriented languages

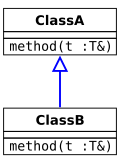

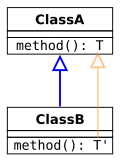

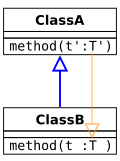

[edit]When a subclass overrides a method in a superclass, the compiler must check that the overriding method has the right type. While some languages require that the type exactly matches the type in the superclass (invariance), it is also type safe to allow the overriding method to have a "better" type. By the usual subtyping rule for function types, this means that the overriding method should return a more specific type (return type covariance), and accept a more general argument (parameter type contravariance). In UML notation, the possibilities are as follows (where Class B is the subclass that extends Class A which is the superclass):

- Variance and method overriding: overview

-

Subtyping of the parameter/return type of the method.

-

Invariance. The signature of the overriding method is unchanged.

-

Covariant return type. The subtyping relation is in the same direction as the relation between ClassA and ClassB.

-

Contravariant parameter type. The subtyping relation is in the opposite direction to the relation between ClassA and ClassB.

-

Covariant parameter type. Not type safe.

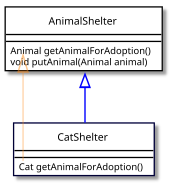

For a concrete example, suppose we are writing a class to model an animal shelter. We assume that Cat is a subclass of Animal, and that we have a base class (using Java syntax)

class AnimalShelter {

Animal getAnimalForAdoption() {

// ...

}

void putAnimal(Animal animal) {

//...

}

}

Now the question is: if we subclass AnimalShelter, what types are we allowed to give to getAnimalForAdoption and putAnimal?

Covariant method return type

[edit]In a language which allows covariant return types, a derived class can override the getAnimalForAdoption method to return a more specific type:

class CatShelter extends AnimalShelter {

Cat getAnimalForAdoption() {

return new Cat();

}

}

Among mainstream OO languages, Java, C++ and C# (as of version 9.0 [7]) support covariant return types. Adding the covariant return type was one of the first modifications of the C++ language approved by the standards committee in 1998.[8] Scala and D also support covariant return types.

Contravariant method parameter type

[edit]Similarly, it is type safe to allow an overriding method to accept a more general argument than the method in the base class:

class CatShelter extends AnimalShelter {

void putAnimal(Object animal) {

// ...

}

}

Only a few object-oriented languages actually allow this (for example, Python when typechecked with mypy). C++, Java and most other languages that support overloading and/or shadowing would interpret this as a method with an overloaded or shadowed name.

However, Sather supported both covariance and contravariance. Calling convention for overridden methods are covariant with out parameters and return values, and contravariant with normal parameters (with the mode in).

Covariant method parameter type

[edit]A couple of mainstream languages, Eiffel and Dart[9] allow the parameters of an overriding method to have a more specific type than the method in the superclass (parameter type covariance). Thus, the following Dart code would type check, with putAnimal overriding the method in the base class:

class CatShelter extends AnimalShelter {

void putAnimal(covariant Cat animal) {

// ...

}

}

This is not type safe. By up-casting a CatShelter to an AnimalShelter, one can try to place a dog in a cat shelter. That does not meet CatShelter parameter restrictions, and will result in a runtime error. The lack of type safety (known as the "catcall problem" in the Eiffel community, where "cat" or "CAT" is a Changed Availability or Type) has been a long-standing issue. Over the years, various combinations of global static analysis, local static analysis, and new language features have been proposed to remedy it,[10][11] and these have been implemented in some Eiffel compilers.

Despite the type safety problem, the Eiffel designers consider covariant parameter types crucial for modeling real world requirements.[11] The cat shelter illustrates a common phenomenon: it is a kind of animal shelter but has additional restrictions, and it seems reasonable to use inheritance and restricted parameter types to model this. In proposing this use of inheritance, the Eiffel designers reject the Liskov substitution principle, which states that objects of subclasses should always be less restricted than objects of their superclass.

One other instance of a mainstream language allowing covariance in method parameters is PHP in regards to class constructors. In the following example, the __construct() method is accepted, despite the method parameter being covariant to the parent's method parameter. Were this method anything other than __construct(), an error would occur:

interface AnimalInterface {}

interface DogInterface extends AnimalInterface {}

class Dog implements DogInterface {}

class Pet

{

public function __construct(AnimalInterface $animal) {}

}

class PetDog extends Pet

{

public function __construct(DogInterface $dog)

{

parent::__construct($dog);

}

}

Another example where covariant parameters seem helpful is so-called binary methods, i.e. methods where the parameter is expected to be of the same type as the object the method is called on. An example is the compareTo method: a.compareTo(b) checks whether a comes before or after b in some ordering, but the way to compare, say, two rational numbers will be different from the way to compare two strings. Other common examples of binary methods include equality tests, arithmetic operations, and set operations like subset and union.

In older versions of Java, the comparison method was specified as an interface Comparable:

interface Comparable {

int compareTo(Object o);

}

The drawback of this is that the method is specified to take an argument of type Object. A typical implementation would first down-cast this argument (throwing an error if it is not of the expected type):

class RationalNumber implements Comparable {

int numerator;

int denominator;

// ...

public int compareTo(Object other) {

RationalNumber otherNum = (RationalNumber)other;

return Integer.compare(numerator * otherNum.denominator,

otherNum.numerator * denominator);

}

}

In a language with covariant parameters, the argument to compareTo could be directly given the desired type RationalNumber, hiding the typecast. (Of course, this would still give a runtime error if compareTo was then called on e.g. a String.)

Avoiding the need for covariant parameter types

[edit]Other language features can provide the apparent benefits of covariant parameters while preserving Liskov substitutability.

In a language with generics (a.k.a. parametric polymorphism) and bounded quantification, the previous examples can be written in a type-safe way.[12] Instead of defining AnimalShelter, we define a parameterized class Shelter<T>. (One drawback of this is that the implementer of the base class needs to foresee which types will need to be specialized in the subclasses.)

class Shelter<T extends Animal> {

T getAnimalForAdoption() {

// ...

}

void putAnimal(T animal) {

// ...

}

}

class CatShelter extends Shelter<Cat> {

Cat getAnimalForAdoption() {

// ...

}

void putAnimal(Cat animal) {

// ...

}

}

Similarly, in recent versions of Java the Comparable interface has been parameterized, which allows the downcast to be omitted in a type-safe way:

class RationalNumber implements Comparable<RationalNumber> {

int numerator;

int denominator;

// ...

public int compareTo(RationalNumber otherNum) {

return Integer.compare(numerator * otherNum.denominator,

otherNum.numerator * denominator);

}

}

Another language feature that can help is multiple dispatch. One reason that binary methods are awkward to write is that in a call like a.compareTo(b), selecting the correct implementation of compareTo really depends on the runtime type of both a and b, but in a conventional OO language only the runtime type of a is taken into account. In a language with Common Lisp Object System (CLOS)-style multiple dispatch, the comparison method could be written as a generic function where both arguments are used for method selection.

Giuseppe Castagna[13] observed that in a typed language with multiple dispatch, a generic function can have some parameters which control dispatch and some "left-over" parameters which do not. Because the method selection rule chooses the most specific applicable method, if a method overrides another method, then the overriding method will have more specific types for the controlling parameters. On the other hand, to ensure type safety the language still must require the left-over parameters to be at least as general. Using the previous terminology, types used for runtime method selection are covariant while types not used for runtime method selection of the method are contravariant. Conventional single-dispatch languages like Java also obey this rule: only one argument is used for method selection (the receiver object, passed along to a method as the hidden argument this), and indeed the type of this is more specialized inside overriding methods than in the superclass.

Castagna suggests that examples where covariant parameter types are superior (particularly, binary methods) should be handled using multiple dispatch; which is naturally covariant. However, most programming languages do not support multiple dispatch.

Summary of variance and inheritance

[edit]The following table summarizes the rules for overriding methods in the languages discussed above.

| Parameter type | Return type | |

|---|---|---|

| C++ (since 1998), Java (since J2SE 5.0), D, C# (since C# 9) | Invariant | Covariant |

| C# (before C# 9) | Invariant | Invariant |

| Sather | Contravariant | Covariant |

| Eiffel | Covariant | Covariant |

Generic types

[edit]In programming languages that support generics (a.k.a. parametric polymorphism), the programmer can extend the type system with new constructors. For example, a C# interface like IList<T> makes it possible to construct new types like IList<Animal> or IList<Cat>. The question then arises what the variance of these type constructors should be.

There are two main approaches. In languages with declaration-site variance annotations (e.g., C#), the programmer annotates the definition of a generic type with the intended variance of its type parameters. With use-site variance annotations (e.g., Java), the programmer instead annotates the places where a generic type is instantiated.

Declaration-site variance annotations

[edit]The most popular languages with declaration-site variance annotations are C# and Kotlin (using the keywords out and in), and Scala and OCaml (using the keywords + and -). C# only allows variance annotations for interface types, while Kotlin, Scala and OCaml allow them for both interface types and concrete data types.

Interfaces

[edit]In C#, each type parameter of a generic interface can be marked covariant (out), contravariant (in), or invariant (no annotation). For example, we can define an interface IEnumerator<T> of read-only iterators, and declare it to be covariant (out) in its type parameter.

interface IEnumerator<out T>

{

T Current { get; }

bool MoveNext();

}

With this declaration, IEnumerator will be treated as covariant in its type parameter, e.g. IEnumerator<Cat> is a subtype of IEnumerator<Animal>.

The type checker enforces that each method declaration in an interface only mentions the type parameters in a way consistent with the in/out annotations. That is, a parameter that was declared covariant must not occur in any contravariant positions (where a position is contravariant if it occurs under an odd number of contravariant type constructors). The precise rule[14][15] is that the return types of all methods in the interface must be valid covariantly and all the method parameter types must be valid contravariantly, where valid S-ly is defined as follows:

- Non-generic types (classes, structs, enums, etc.) are valid both co- and contravariantly.

- A type parameter

Tis valid covariantly if it was not markedin, and valid contravariantly if it was not markedout. - An array type

A[]is valid S-ly ifAis. (This is because C# has covariant arrays.) - A generic type

G<A1, A2, ..., An>is valid S-ly if for each parameterAi,- Ai is valid S-ly, and the ith parameter to

Gis declared covariant, or - Ai is valid (not S)-ly, and the ith parameter to

Gis declared contravariant, or - Ai is valid both covariantly and contravariantly, and the ith parameter to

Gis declared invariant.

- Ai is valid S-ly, and the ith parameter to

As an example of how these rules apply, consider the IList<T> interface.

interface IList<T>

{

void Insert(int index, T item);

IEnumerator<T> GetEnumerator();

}

The parameter type T of Insert must be valid contravariantly, i.e. the type parameter T must not be tagged out. Similarly, the result type IEnumerator<T> of GetEnumerator must be valid covariantly, i.e. (since IEnumerator is a covariant interface) the type T must be valid covariantly, i.e. the type parameter T must not be tagged in. This shows that the interface IList is not allowed to be marked either co- or contravariant.

In the common case of a generic data structure such as IList, these restrictions mean that an out parameter can only be used for methods getting data out of the structure, and an in parameter can only be used for methods putting data into the structure, hence the choice of keywords.

Data

[edit]C# allows variance annotations on the parameters of interfaces, but not the parameters of classes. Because fields in C# classes are always mutable, variantly parameterized classes in C# would not be very useful. But languages which emphasize immutable data can make good use of covariant data types. For example, in all of Scala, Kotlin and OCaml the immutable list type is covariant: List[Cat] is a subtype of List[Animal].

Scala's rules for checking variance annotations are essentially the same as C#'s. However, there are some idioms that apply to immutable datastructures in particular. They are illustrated by the following (excerpt from the) definition of the List[A] class.

sealed abstract class List[+A] extends AbstractSeq[A] {

def head: A

def tail: List[A]

/** Adds an element at the beginning of this list. */

def ::[B >: A] (x: B): List[B] =

new scala.collection.immutable.::(x, this)

/** ... */

}

First, class members that have a variant type must be immutable. Here, head has the type A, which was declared covariant (+), and indeed head was declared as a method (def). Trying to declare it as a mutable field (var) would be rejected as type error.

Second, even if a data structure is immutable, it will often have methods where the parameter type occurs contravariantly. For example, consider the method :: which adds an element to the front of a list. (The implementation works by creating a new object of the similarly named class ::, the class of nonempty lists.) The most obvious type to give it would be

def :: (x: A): List[A]

However, this would be a type error, because the covariant parameter A appears in a contravariant position (as a function parameter). But there is a trick to get around this problem. We give :: a more general type, which allows adding an element of any type B

as long as B is a supertype of A. Note that this relies on List being covariant, since

this has type List[A] and we treat it as having type List[B]. At first glance it may not be obvious that the generalized type is sound, but if the programmer starts out with the simpler type declaration, the type errors will point out the place that needs to be generalized.

Inferring variance

[edit]It is possible to design a type system where the compiler automatically infers the best possible variance annotations for all datatype parameters.[16] However, the analysis can get complex for several reasons. First, the analysis is nonlocal since the variance of an interface I depends on the variance of all interfaces that I mentions. Second, in order to get unique best solutions the type system must allow bivariant parameters (which are simultaneously co- and contravariant). And finally, the variance of type parameters should arguably be a deliberate choice by the designer of an interface, not something that just happens.

For these reasons[17] most languages do very little variance inference. C# and Scala do not infer any variance annotations at all. OCaml can infer the variance of parameterized concrete datatypes, but the programmer must explicitly specify the variance of abstract types (interfaces).

For example, consider an OCaml datatype T which wraps a function

type ('a, 'b) t = T of ('a -> 'b)

The compiler will automatically infer that T is contravariant in the first parameter, and covariant in the second. The programmer can also provide explicit annotations, which the compiler will check are satisfied. Thus the following declaration is equivalent to the previous one:

type (-'a, +'b) t = T of ('a -> 'b)

Explicit annotations in OCaml become useful when specifying interfaces. For example, the standard library interface Map.S for association tables include an annotation saying that the map type constructor is covariant in the result type.

module type S =

sig

type key

type (+'a) t

val empty: 'a t

val mem: key -> 'a t -> bool

...

end

This ensures that e.g. cat IntMap.t is a subtype of animal IntMap.t.

Use-site variance annotations (wildcards)

[edit]One drawback of the declaration-site approach is that many interface types must be made invariant. For example, we saw above that IList needed to be invariant, because it contained both Insert and GetEnumerator. In order to expose more variance, the API designer could provide additional interfaces which provide subsets of the available methods (e.g. an "insert-only list" which only provides Insert). However this quickly becomes unwieldy.

Use-site variance means the desired variance is indicated with an annotation at the specific site in the code where the type will be used. This gives users of a class more opportunities for subtyping without requiring the designer of the class to define multiple interfaces with different variance. Instead, at the point a generic type is instantiated to an actual parameterized type, the programmer can indicate that only a subset of its methods will be used. In effect, each definition of a generic class also makes available interfaces for the covariant and contravariant parts of that class.

Java provides use-site variance annotations through wildcards, a restricted form of bounded existential types. A parameterized type can be instantiated by a wildcard ? together with an upper or lower bound, e.g. List<? extends Animal> or List<? super Animal>. An unbounded wildcard like List<?> is equivalent to List<? extends Object>. Such a type represents List<X> for some unknown type X which satisfies the bound.[4]: 139 For example, if l has type List<? extends Animal>, then the type checker will accept

Animal a = l.get(3);

because the type X is known to be a subtype of Animal, but

l.add(new Animal());

will be rejected as a type error since an Animal is not necessarily an X. In general, given some interface I<T>, a reference to an I<? extends T> forbids using methods from the interface where T occurs contravariantly in the type of the method. Conversely, if l had type List<? super Animal> one could call l.add but not l.get.

While non-wildcard parameterized types in Java are invariant (e.g. there is no subtyping relationship between List<Cat> and List<Animal>), wildcard types can be made more specific by specifying a tighter bound. For example, List<? extends Cat> is a subtype of List<? extends Animal>. This shows that wildcard types are covariant in their upper bounds (and also contravariant in their lower bounds). In total, given a wildcard type like C<? extends T>, there are three ways to form a subtype: by specializing the class C, by specifying a tighter bound T, or by replacing the wildcard ? with a specific type (see figure).[4]: 139

By applying two of the above three forms of subtyping, it becomes possible to, for example, pass an argument of type List<Cat> to a method expecting a List<? extends Animal>. This is the kind of expressiveness that results from covariant interface types. The type List<? extends Animal> acts as an interface type containing only the covariant methods of List<T>, but the implementer of List<T> did not have to define it ahead of time.

In the common case of a generic data structure IList, covariant parameters are used for methods getting data out of the structure, and contravariant parameters for methods putting data into the structure. The mnemonic for Producer Extends, Consumer Super (PECS), from the book Effective Java by Joshua Bloch gives an easy way to remember when to use covariance and contravariance.[4]: 141

Wildcards are flexible, but there is a drawback. While use-site variance means that API designers need not consider variance of type parameters to interfaces, they must often instead use more complicated method signatures. A common example involves the Comparable interface.[4]: 66 Suppose we want to write a function that finds the biggest element in a collection. The elements need to implement the compareTo method,[4]: 66 so a first try might be

<T extends Comparable<T>> T max(Collection<T> coll);

However, this type is not general enough—one can find the max of a Collection<Calendar>, but not a Collection<GregorianCalendar>. The problem is that GregorianCalendar does not implement Comparable<GregorianCalendar>, but instead the (better) interface Comparable<Calendar>. In Java, unlike in C#, Comparable<Calendar> is not considered a subtype of Comparable<GregorianCalendar>. Instead the type of max has to be modified:

<T extends Comparable<? super T>> T max(Collection<T> coll);

The bounded wildcard ? super T conveys the information that max calls only contravariant methods from the Comparable interface. This particular example is frustrating because all the methods in Comparable are contravariant, so that condition is trivially true. A declaration-site system could handle this example with less clutter by annotating only the definition of Comparable.

The max method can be changed even further by using an upper bounded wildcard for the method parameter:[18]

<T extends Comparable<? super T>> T max(Collection<? extends T> coll);

Comparing declaration-site and use-site annotations

[edit]Use-site variance annotations provide additional flexibility, allowing more programs to type check. However, they have been criticized for the complexity they add to the language, leading to complicated type signatures and error messages.

One way to assess whether the extra flexibility is useful is to see if it is used in existing programs. A survey of a large set of Java libraries[16] found that 39% of wildcard annotations could have been directly replaced by declaration-site annotations. Thus the remaining 61% is an indication of places where Java benefits from having the use-site system available.

In a declaration-site language, libraries must either expose less variance, or define more interfaces. For example, the Scala Collections library defines three separate interfaces for classes which employ covariance: a covariant base interface containing common methods, an invariant mutable version which adds side-effecting methods, and a covariant immutable version which may specialize the inherited implementations to exploit structural sharing.[19] This design works well with declaration-site annotations, but the large number of interfaces carry a complexity cost for clients of the library. And modifying the library interface may not be an option—in particular, one goal when adding generics to Java was to maintain binary backwards compatibility.

On the other hand, Java wildcards are themselves complex. In a conference presentation[20] Joshua Bloch criticized them as being too hard to understand and use, stating that when adding support for closures "we simply cannot afford another wildcards". Early versions of Scala used use-site variance annotations but programmers found them difficult to use in practice, while declaration-site annotations were found to be very helpful when designing classes.[21] Later versions of Scala added Java-style existential types and wildcards; however, according to Martin Odersky, if there were no need for interoperability with Java then these would probably not have been included.[22]

Ross Tate argues[23] that part of the complexity of Java wildcards is due to the decision to encode use-site variance using a form of existential types. The original proposals[24][25] used special-purpose syntax for variance annotations, writing List<+Animal> instead of Java's more verbose List<? extends Animal>.

Since wildcards are a form of existential types they can be used for more things than just variance. A type like List<?> ("a list of unknown type"[26]) lets objects be passed to methods or stored in fields without exactly specifying their type parameters. This is particularly valuable for classes such as Class where most of the methods do not mention the type parameter.

However, type inference for existential types is a difficult problem. For the compiler implementer, Java wildcards raise issues with type checker termination, type argument inference, and ambiguous programs.[27] In general it is undecidable whether a Java program using generics is well-typed or not,[28] so any type checker will have to go into an infinite loop or time out for some programs. For the programmer, it leads to complicated type error messages. Java type checks wildcard types by replacing the wildcards with fresh type variables (so-called capture conversion). This can make error messages harder to read, because they refer to type variables that the programmer did not directly write. For example, trying to add a Cat to a List<? extends Animal> will give an error like

method List.add (capture#1) is not applicable (actual argument Cat cannot be converted to capture#1 by method invocation conversion) where capture#1 is a fresh type-variable: capture#1 extends Animal from capture of ? extends Animal

Since both declaration-site and use-site annotations can be useful, some type systems provide both.[16][23]

Etymology

[edit]These terms come from the notion of covariant and contravariant functors in category theory. Consider the category whose objects are types and whose morphisms represent the subtype relationship ≤. (This is an example of how any partially ordered set can be considered as a category.) Then for example the function type constructor takes two types p and r and creates a new type p → r; so it takes objects in to objects in . By the subtyping rule for function types this operation reverses ≤ for the first parameter and preserves it for the second, so it is a contravariant functor in the first parameter and a covariant functor in the second.

See also

[edit]- Polymorphism (computer science)

- Inheritance (object-oriented programming)

- Liskov substitution principle

References

[edit]- ^ This only happens in a pathological case. For example,

I<T> = int: any type can be put in forTand the result is stillint. - ^ a b c Skeet, Jon (23 March 2019). C# in Depth. Manning. ISBN 978-1617294532.

- ^ Func<T, TResult> Delegate - MSDN Documentation

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bloch, Joshua (2018). "Effective Java: Programming Language Guide" (third ed.). Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0134685991.

- ^ Reynolds, John C. (1981). The Essence of Algol. Symposium on Algorithmic Languages. North-Holland.

- ^

Cardelli, Luca (1984). A semantics of multiple inheritance (PDF). Semantics of Data Types (International Symposium Sophia-Antipolis, France, June 27–29, 1984). Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 173. Springer. pp. 51–67. doi:10.1007/3-540-13346-1_2. ISBN 3-540-13346-1.

Longer version: — (February 1988). "A semantics of multiple inheritance". Information and Computation. 76 (2/3): 138–164. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.116.1298. doi:10.1016/0890-5401(88)90007-7. - ^ Torgersen, Mads. "C# 9.0 on the record".

- ^ Allison, Chuck. "What's New in Standard C++?".

- ^ "Fixing Common Type Problems". Dart Programming Language.

- ^ Bertrand Meyer (October 1995). "Static Typing" (PDF). OOPSLA 95 (Object-Oriented Programming, Systems, Languages and Applications), Atlanta, 1995.

- ^ a b Howard, Mark; Bezault, Eric; Meyer, Bertrand; Colnet, Dominique; Stapf, Emmanuel; Arnout, Karine; Keller, Markus (April 2003). "Type-safe covariance: Competent compilers can catch all catcalls" (PDF). Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- ^ Franz Weber (1992). "Getting Class Correctness and System Correctness Equivalent - How to Get Covariance Right". TOOLS 8 (8th conference on Technology of Object-Oriented Languages and Systems), Dortmund, 1992. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.52.7872.

- ^ Castagna, Giuseppe (May 1995). "Covariance and contravariance: conflict without a cause". ACM Transactions on Programming Languages and Systems. 17 (3): 431–447. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.115.5992. doi:10.1145/203095.203096. S2CID 15402223.

- ^ Lippert, Eric (3 December 2009). "Exact rules for variance validity". Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- ^ "Section II.9.7". ECMA International Standard ECMA-335 Common Language Infrastructure (CLI) (6th ed.). June 2012.

- ^ a b c Altidor, John; Shan, Huang Shan; Smaragdakis, Yannis (2011). "Taming the wildcards: combining definition- and use-site variance". Proceedings of the 32nd ACM SIGPLAN conference on Programming language design and implementation (PLDI'11). ACM. pp. 602–613. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.225.8265. doi:10.1145/1993316.1993569. ISBN 9781450306638.

- ^ Lippert, Eric (October 29, 2007). "Covariance and Contravariance in C# Part Seven: Why Do We Need A Syntax At All?". Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- ^ Bloch 2018, pp. 139–145, Chapter §5 Item 31: Use bounded wildcards to increase API flexibility.

- ^ Odersky, Marin; Spoon, Lex (September 7, 2010). "The Scala 2.8 Collections API". Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- ^ Bloch, Joshua (November 2007). "The Closures Controversy [video]". Presentation at Javapolis'07. Archived from the original on 2014-02-02.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Odersky, Martin; Zenger, Matthias (2005). "Scalable component abstractions" (PDF). Proceedings of the 20th annual ACM SIGPLAN conference on Object-oriented programming, systems, languages, and applications (OOPSLA '05). ACM. pp. 41–57. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.176.5313. doi:10.1145/1094811.1094815. ISBN 1595930310.

- ^ Venners, Bill; Sommers, Frank (May 18, 2009). "The Purpose of Scala's Type System: A Conversation with Martin Odersky, Part III". Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- ^ a b Tate, Ross (2013). "Mixed-Site Variance". FOOL '13: Informal Proceedings of the 20th International Workshop on Foundations of Object-Oriented Languages. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.353.4691.

- ^ Igarashi, Atsushi; Viroli, Mirko (2002). "On Variance-Based Subtyping for Parametric Types". Proceedings of the 16th European Conference on Object-Oriented Programming (ECOOP '02). Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 2374. pp. 441–469. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.66.450. doi:10.1007/3-540-47993-7_19. ISBN 3-540-47993-7.

- ^ Thorup, Kresten Krab; Torgersen, Mads (1999). "Unifying Genericity: Combining the Benefits of Virtual Types and Parameterized Classes". Object-Oriented Programming (ECOOP '99). Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 1628. Springer. pp. 186–204. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.91.9795. doi:10.1007/3-540-48743-3_9. ISBN 3-540-48743-3.

- ^ "The Java™ Tutorials, Generics (Updated), Unbounded Wildcards". Retrieved July 17, 2020.

- ^ Tate, Ross; Leung, Alan; Lerner, Sorin (2011). "Taming wildcards in Java's type system". Proceedings of the 32nd ACM SIGPLAN conference on Programming language design and implementation (PLDI '11). pp. 614–627. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.739.5439. ISBN 9781450306638.

- ^ Grigore, Radu (2017). "Java generics are turing complete". Proceedings of the 44th ACM SIGPLAN Symposium on Principles of Programming Languages (POPL'17). pp. 73–85. arXiv:1605.05274. Bibcode:2016arXiv160505274G. ISBN 9781450346603.

External links

[edit]- Fabulous Adventures in Coding: An article series about implementation concerns surrounding co/contravariance in C#

- Contra Vs Co Variance (note this article is not updated about C++)

- Closures for the Java 7 Programming Language (v0.5)

- The theory behind covariance and contravariance in C# 4