Van Diemen's Land

| Van Diemen's Land | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

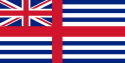

| British Crown Colony | |||||||||

| 1825–1856 | |||||||||

1828 map | |||||||||

| Anthem | |||||||||

| God Save the King/Queen | |||||||||

| Capital | Hobart | ||||||||

| Demonym | Van Diemonian (usually spelt Vandemonian) | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 1851 | 70,130 | ||||||||

| Government | |||||||||

| • Type | Self-governing colony | ||||||||

| Monarch | |||||||||

• 1825–1830 | George IV | ||||||||

• 1830–1837 | William IV | ||||||||

• 1837–1856 | Victoria | ||||||||

| Lieutenant-Governor | |||||||||

• 1825–1836 | Sir George Arthur first | ||||||||

• 1855–1856 | Sir Henry Young last | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Independence from the Colony of New South Wales | 3 December 1825 | ||||||||

• Name changed to Tasmania and self-rule | 1856 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Australia | ||||||||

1852 map of Van Diemen's Land | |

| |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Southern Ocean |

| Coordinates | 42°00′S 147°00′E / 42.000°S 147.000°E |

| Area | 68,401 km2 (26,410 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 1,614 m (5295 ft) |

| Highest point | Mount Ossa |

| Administration | |

Australia | |

| Largest settlement | Hobart Town |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 70,130 (1851) |

| Pop. density | 1.03/km2 (2.67/sq mi) |

| Ethnic groups | European Australians, Aboriginal Tasmanians |

Van Diemen's Land was the colonial name of the island of Tasmania used by the British during the European exploration and colonisation of Australia in the 19th century. The island was previously discovered and named by the Dutch in 1642. Explorer Abel Tasman discovered the island, working under the sponsorship of Anthony van Diemen, the Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies. The British retained the name when they established a settlement in 1803 before it became a separate colony in 1825. Its penal colonies became notorious destinations for the transportation of convicts due to the harsh environment, isolation and reputation for being inescapable.

The name was changed to Tasmania in 1 January 1856 to disassociate the island from its convict past and to honour its discoverer, Abel Tasman. The old name had become a byword for horror in England because of the severity of its convict settlements such as Macquarie Harbour and Port Arthur. When the island became a self-governing colony in 1855, one of the first acts of the new legislature was to change its name.[1]

With the passing of the Australian Constitutions Act 1850, Van Diemen's Land (along with New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia, Victoria, and Western Australia) was granted responsible self-government with its own elected representative and parliament. The last penal settlement in Tasmania was closed in 1877.

Toponym

[edit]The island was named in honour of Anthony van Diemen, Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies who had sent the Dutch explorer Abel Tasman on his voyage of discovery in the 1640s. In 1642 Tasman became the first known European to land on the shores of Tasmania. After landing at Blackman Bay and later raising the Dutch flag at North Bay, Tasman named the island Anthoonij van Diemenslandt (Anthony Van Diemen's land) in his patron's honour.

The demonym for inhabitants of Van Diemen's Land was "Van Diemonian", though contemporaries used the spelling "Vandemonian".[2] Anthony Trollope used the latter term; "They are (the Vandemonians) united in their declaration that the cessation of the coming of convicts has been their ruin."[3]

In 1856, Van Diemen's Land was renamed Tasmania, removing the unsavoury link the name Van Diemen's Land had with its penal settlements (and the "demon" connotation). Tasmania was chosen as it honoured the explorer Abel Tasman, the first European to visit the island. Within 21 years the last penal settlement in Tasmania at Port Arthur was permanently closed in 1877.[4]

History

[edit]Exploration

[edit]

In 1642, Abel Tasman discovered the western side of the island and named it on behalf of the Dutch. He sailed around the south to the east, landing at Blackman Bay and assumed it was part of the Australian mainland.

Between 1772 and 1798, recorded European visits were only to the southeastern portion of the island and it was not known to be an island until Matthew Flinders and George Bass circumnavigated it in the sloop Norfolk in 1798–1799.

In 1773, Tobias Furneaux in HMS Adventure, explored a great part of the south and east coasts of Van Diemen's Land and made the earliest British chart of the island.[5] He discovered the opening to D'Entrecasteaux Channel and, at Bruny Island, named Adventure Bay for his ship.[6][7]

In 1777, James Cook took on water and wood in Tasmania and became cursorily acquainted with some indigenous peoples on his third voyage of discovery. Cook named the Furneaux Group of islands at the eastern entrance to Bass Strait and the group now known as the Low Archipelago.[8][9]

From at least the settlement of New South Wales, sealers and whalers operated in the surrounding waters and explored parts.

In January 1793, a French expedition under the command of Antoine Bruni d'Entrecasteaux anchored in Recherche Bay and a period of five weeks was spent in that area, carrying out explorations into both natural history and geography. A few months later, British East India Company Captain John Hayes, with the ships Duke of Clarence and Duchess, resupplied with wood and water at Adventure Bay and explored and named the Derwent River and many surrounding features.[10]

In 1802 and 1803, the French expedition commanded by Nicolas Baudin explored D'Entrecasteaux Channel and Maria Island and carried out charting of Bass Strait. Baudin had been associated, like Peyroux, with the resettlement of the Acadians from French Canada -- mostly from what is now called the New Brunswick–Nova Scotia area -- to Louisiana.

Early colonisation

[edit]Around 1784–1785, Henri Peyroux de la Coudrenière, a serial entrepreneur in colonial schemes, wrote a "memoir on the advantages to be gained for the Spanish crown by the settlement of Van Diemen's Land".[11] After receiving no response from the Spanish government, Peyroux proposed it to the French government, as "Mémoire sur les avantages qui résulteraient d'une colonie puissante à la terre de Diémen" but nothing came of his scheme.[12]

Sealers and whalers based themselves on the Tasmanian islands from 1798.

In August 1803, New South Wales Governor Philip King sent Lieutenant John Bowen to establish a small military outpost on the eastern shore of the Derwent River to forestall any claims to the island arising from the activities of the French explorers.

From 24 September 1804 until 4 February 1813, there were two administrative divisions in Van Diemen's Land, Cornwall County in the north and Buckingham County in the south. The border between the counties was defined as the 42nd parallel (now between Trial Harbour and Friendly Beaches). Cornwall County was administered by William Paterson while Buckingham County was administered by David Collins.[13][14]

Major-General Ralph Darling was appointed Governor of New South Wales in 1825. In the same year he visited Hobart Town. On 3 December of 1825, he proclaimed the establishment of the independent colony, of which he became governor for three days.[15]

In 1836, the new governor, Sir John Franklin, sailed to Van Diemen's Land, together with William Hutchins (1792-1841), who was to become the colony's first Archdeacon.[16]

In 1856, the colony was granted responsible self-government with its representative parliament, and the name of the island and colony was officially changed to Tasmania on 1 January 1856.[17][18]

Penal colony

[edit]From the early 1800s to the 1853 abolition of penal transportation (known simply as "transportation"), Van Diemen's Land was the primary penal colony in Australia. Following the suspension of transportation to New South Wales, all transported convicts were sent to Van Diemen's Land. In total, some 73,000 convicts were transported to Van Diemen's Land or about 40% of all convicts sent to Australia.[19]

Male convicts served their sentences as assigned labour to free settlers or in gangs assigned to public works. Only the most difficult convicts (mostly re-offenders) were sent to the Tasman Peninsula prison known as Port Arthur. Female convicts were assigned as servants in free settler households or sent to a female factory (women's workhouse prison). There were five female factories in Van Diemen's Land.

Convicts completing their sentences or earning their ticket-of-leave often promptly left Van Diemen's Land. Many settled in the new free colony of Victoria, to the dismay of the free settlers in towns such as Melbourne.

On 6 August 1829, the brig Cyprus, a government-owned vessel used to transport goods, people, and convicts, set sail from Hobart Town for Macquarie Harbour Penal Station on a routine voyage carrying supplies and convicts. While the ship was becalmed in Recherche Bay, convicts allowed on deck attacked their guards and took control of the brig. The mutineers marooned officers, soldiers, and convicts who did not join the mutiny without supplies. The convicts then sailed the Cyprus to Canton, China, where they scuttled her and claimed to be castaways from another vessel. On the way, Cyprus visited Japan during the height of the period of severe Japanese restrictions on the entry of foreigners, the first Australian ship to do so.

Tensions sometimes ran high between the settlers and the "Vandemonians" as they were termed, particularly during the Victorian gold rush when a flood of settlers from Van Diemen's Land rushed to the Victorian goldfields.

Complaints from Victorians about recently released convicts from Van Diemen's Land re-offending in Victoria was one of the contributing reasons for the eventual abolition of transportation to Van Diemen's Land in 1853.[20]

Demographics

[edit]Population summary

[edit]According to the 1851 Census of Van Diemen's Land, there was a total population of 70,130 individuals, with 62.85% being males and 37.14% being females. Non-convicts, i.e. free people, comprised 75.6% of the population and convicts, 24.3%, which was an increase since the 1848 Census. Of the males who were not a part of the Military, or convicts on public works, 71% were free and 28.57% were bond. Of the females who were not part of the Military, or convicts on public works, 84.15% were free and 15.84% were bond.

| Males | Females | |

|---|---|---|

| Emigrants | 24.8% | 32.5% |

| Born in the Colony | 34.7% | 51% |

| Have been Prisoners | 40.3% | 16.5% |

| Males | Females | |

|---|---|---|

| Holding Tickets-of-Leave | 58% | 31% |

| In Government employment | 13.7% | 32.5% |

| In private Assignment | 14.5% | 14.9% |

| In private employment | 13.28% | 21.5% |

Religion

[edit]| Religion | Persons | Percentages |

|---|---|---|

| Church of England | 46,068 | 65.69% |

| Church of Scotland | 4,572 | 6.52% |

| Wesleyans | 3,850 | 5.49% |

| Other Protestant Dissenters | 2,426 | 3.46% |

| Roman Catholics | 12,693 | 18.10% |

| Jews | 441 | 0.63% |

Popular culture

[edit]Film

[edit]- The 2008 film The Last Confession of Alexander Pearce tells the true story of Alexander Pearce through his final confession to fellow Irishman and colonial priest Philip Conolly. The film was nominated for a Rose d'Or, an Irish Film and Television Award, an Australian Film Institute Award and won an IF Award in 2009.

- The 2009 film Van Diemen's Land follows the story of the infamous Irish convict Alexander Pearce and his escape with seven other convicts.

- The 2011 Australian drama film The Hunter, about a shadowy corporation that sends a mercenary to Tasmania to track down a thylacine, a supposedly extinct animal whose genetic code holds the secret to a dangerous weapon.

- The 2013 ABC telemovie The Outlaw Michael Howe is set in Van Diemen's Land and tells the story of bushranger Michael Howe's convict-led rebellion.

- The 2018 film Black '47 directed by Lance Daly and set in Ireland during the Great Irish Famine depicts a judgement imposed on a farmer for theft by a judge in the province of Connemara, which includes six months of hard labour and subsequent penal transportation to Van Diemen's Land.

- The 2018 film The Nightingale is set in Van Diemen's Land in 1825 and depicts a female Irish convict taking revenge for the murder of her family by the colonial forces of Australia as the Black War breaks out.

Music

[edit]- U2 recorded the song "Van Diemen's Land" for their 1988 album Rattle and Hum, with lyrics expressing the plight of a man facing transportation.[21]

- Tom Russell sets Van Diemen's Land as the ship's destination in his song "Isaac Lewis" on the album "Modern Art".

- In the traditional Irish folk song "The Black Velvet Band", the protagonist is found guilty of stealing a watch and is sent to Van Diemen's Land as punishment.

- The song "Van Diemen's Land" in the album titled "Parcel of Rogues" with vocals by Barbara Dickson is about an Irish man caught for poaching and transported to Van Diemen's Land and the hardships he has living there.

- Russell Morris released an album titled "Van Diemen's Land" in Australia in 2014. The title track describes the voyage of a convict being transported to Van Diemen's Land and was released with a video shot in Tasmania.

- The Roud Folk Song Index includes two different English transportation ballads with the title Van Diemen's Land, both about a poacher sentenced to transportation to the penal colony.

- The album "Fred Holstein: A Collection" includes Fred Holstein's version of the classic folk song "Maggie May" (Maggie May (folk song), which is different from Rod Stewart's Maggie May). In his version, the prostitute and thief Maggie May is transported to "Van Diemen's cruel shore."

- Ewan McColl recorded the transportation song "Van Diemen's Land," releasing it on the Riverside Records long-playing album "Scots Streets Songs," and also released the song as a 45-rpm single.

- The Fields Of Athenrye: Depicting a young girl saying goodbye to her partner as he's being transported to Van Diemen's land for stealing "Trevelyan's corn"

Literature

[edit]

- Emily Dickinson's 1890 poem, "If you were coming in the fall" makes reference to Van Diemen's land with the line "Subtracting, til my fingers dropped, Into Van Dieman's Land.".

- The novel, The Broad Arrow: Being Passages from the History of Maida Gwynnham, a Lifer (published in 1859 in London and in 1860 in Hobart) was written in the penal colony, under the pen name Oliné Keese.[22]

- Australian winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature Patrick White's novel A Fringe of Leaves places much of the novel's beginnings in Van Diemen's Land.

- Van Diemen's Land is the setting of Richard Flanagan's novels Gould's Book of Fish: A Novel in Twelve Fish (2002) and Wanting (2008).

- Brendan Whiting's book Victims of Tyranny, gives an account of the lives of the Irish rebels, the Fitzgerald convict brothers who were sent to help open up the north of Van Diemen's Land in 1805, under the leadership of the explorer Colonel William Paterson.

- In Cormac McCarthy's novel Blood Meridian, one of the characters in the Glanton Gang of scalpers in 1850s Mexico is a "Vandiemenlander" named Bathcat. Born in Wales he later went to Australia to hunt aborigines, and eventually came to Mexico, where he uses those skills on the Apaches.

- From The Potato Factory by Bryce Courtenay (1995), "... subtracting till my fingers dropped; into Van Diemen's Land." This is a quote from Emily Dickinson's Poem "If You Were Coming in the Fall". Two of the main characters in Cortenay's novel are transported Van Diemen's Land as convicts and another travels there, where around half of the novel takes place.

- In the novel The Convicts by Iain Lawrence, young Tom Tin is sent to Van Diemen's Land on charges of murder.

- In the novel The Terror by Dan Simmons (2007). In this novel about the ill-fated exploration by HMS Erebus and HMS Terror to discover the Northwest Passage. The ships left England in May 1846 and were never heard from again, although since then much has been discovered about the fate of the 129 officers and crew. References are made to Van Diemen's Land during the chapters devoted to Francis Crozier.

- Van Diemen's Land is the setting of the novel English Passengers by Matthew Kneale (2000), which tells the story of three eccentric Englishmen who in 1857 set sail for the island in search of the Garden of Eden. The story runs parallel with the narrative of a young Tasmanian who tells the struggle of the indigenous population and the desperate battle against the invading British colonists.

- Christopher Koch's novel Out of Ireland (1999) describes life as a convict in Van Diemen's Land.

- Marcus Clarke used historical events as the basis for his fictional For the Term of his Natural Life (1870), the story of a gentleman, falsely convicted of murder, who is transported to Van Diemen's Land.

- Julian Stockwin's nautical fiction series, The Kydd Series, includes the book Command (2006) in which Thomas Kydd takes a ship to Van Diemen's Land, at the behest of then governor of New South Wales, Philip Gidley King, for the purpose of preventing French explorers from establishing a French settlement on the island.

- "The Exiles" by Christina Baker Kline (2020) tells the story of "transportation" to Van Dieman's Land and the hardship, oppression, opportunity and hope of three women at the centre of the story.

See also

[edit]- Cape Grim massacre

- Cyprus mutiny

- Colony of Tasmania

- Governors of Tasmania

- Van Diemen's Land Company

- Apostolic Vicariate of New Holland and Van Diemen's Land (Catholic missionary jurisdiction)

Notes

[edit]- ^ The name "Van Diemen's Land" name was retained when British settlement began there in 1803. It became a byword for horror in England because of the severity of its convict settlements such as Port Arthur and Macquarie Harbour. The name had acquired such odium that when it became a self-governing colony in 1855, one of the first acts of the new legislature was to change its name to Tasmania. "Tasmania is preferred, because 'Van Diemen's Land' is associated among all nations with bondage and guilt" John West remarked at the opening of his History of Tasmania (Launceston: Dowling) 1852, vol I:4). But the old name lingered for many years—Tasmanians were referred to as Vandemonians until the turn of the century.

- ^ "Vandemonian – definition of Vandemonian by the Free Online Dictionary, Thesaurus and Encyclopedia". Thefreedictionary.com. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- ^ quoted by Patsy Adam Smith p.248 of Smith, Patsy Adam and Woodberry, Joan (1977) Historic Tasmania Sketchbook Rigby ISBN 0-7270-0286-4

- ^ "Port Arthur Historic Site". Australian Government, National Heritage site.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 11 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 362.

- ^ Furneaux, Tobias, Captain Furneaux's Narrative, with some Account of Van Diemen's Land.

- ^ Sketch of Van Diemen Land, National Library of Australia Map nk-2456-50

- ^ Chisholm 1911.

- ^ Sprod, Dan (2005). "Furneaux, Tobias (1735–1781)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943. Retrieved 5 May 2008.

- ^ Lee, Ida (1912). Commodore Sir John Hayes His Voyage and Life (1767-1831) with some account of Admiral d'Entrecasteaux's voyage of 1792–3. Longmans, Green, and Co.

- ^ Liljegren, E. R. (1939). "Jacobinism in Spanish Louisiana, 1792–1797". Louisiana Historical Quarterly. 22 (1): 47–97. ISSN 0095-5949.

- ^ Paul Roussier, "Un projet de colonie française dans le Pacifique à la fin du XVIII siecle", La Revue du Pacifique, Année 6, No.1, 15 Janvier 1927, pp.726–733.[1]; Robert J. King, "Henri Peyroux de la Coudrenière and his plan for a colony in Van Diemen's Land", Map Matters, Issue 31, June 2017, pp.2–6.[2] Archived 13 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Constitutional Events". Tasmanian Parliamentary Library. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ "Colonel Collins' Commission 14 January 1803 (NSW)". Museum of Australian Democracy. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ "150th Anniversary of Australia". The Mercury. Hobart, Tasmania. 26 January 1938. p. 6. Retrieved 26 January 2012 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Lewis, Donald M (2004). Dictionary of Evangelical Biography. Peabody, Mass, USA: Hendrikson Publishers. p. 587. ISBN 1565639359.

- ^ Newman, Terry. "Appendix 2 Select chronology of renaming". Becoming Tasmania Companion Web Site. Parliament of Tasmania. Archived from the original on 1 January 2019.

- ^ "About Van Diemen's Land". VanDiemensLand.com. Archived from the original on 26 January 2014.

- ^ Maxwell-Stewart, Hamish. "The state, convicts and longitudinal analysis." Australian Historical Studies 47, no. 3 (2016): 414-429.

- ^ Fletcher, B. H. (1994). 1770–1850. In S. Bambrick (Ed.), The Cambridge encyclopedia of Australia (pp. 86–94). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ "U2 > Discography > Lyrics > Van Diemen's Land". U2.com. Retrieved 16 July 2022.

- ^ Caroline Woolmer Leaky Archived 25 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Index of Significant Tasmanian Women, Department of Premier and Cabinet, Government of Tasmania.

References

[edit]- Alexandra, Rieck (editor) (2005) The Companion to Tasmanian History Centre for Tasmanian Historical Studies, University of Tasmania, Hobart. ISBN 1-86295-223-X.

- Boyce, James (2008), Van Diemen's Land. Black Inc., Melbourne. ISBN 978-1-86395-413-6.

- Robson, L.L. (1983) A history of Tasmania. Volume 1. Van Diemen's Land from the earliest times to 1855 Melbourne, Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-554364-5.

- Robson, L.L. (1991) A history of Tasmania. Volume II. Colony and state from 1856 to the 1980s Melbourne, Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-553031-4.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Van Diemen's Land at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Van Diemen's Land at Wikimedia Commons