False vacuum

| Part of a series on |

| Physical cosmology |

|---|

|

In quantum field theory, a false vacuum[1] is a hypothetical vacuum state that is locally stable but does not occupy the most stable possible ground state.[2] In this condition it is called metastable. It may last for a very long time in this state, but could eventually decay to the more stable one, an event known as false vacuum decay. The most common suggestion of how such a decay might happen in our universe is called bubble nucleation – if a small region of the universe by chance reached a more stable vacuum, this "bubble" (also called "bounce")[3][4] would spread.

A false vacuum exists at a local minimum of energy and is therefore not completely stable, in contrast to a true vacuum, which exists at a global minimum and is stable.

Definition of true vs. false vacuum

[edit]A vacuum is defined as a space with as little energy in it as possible. Despite the name, the vacuum still has quantum fields. A true vacuum is stable because it is at a global minimum of energy, and is commonly assumed to coincide with the physical vacuum state we live in. It is possible that a physical vacuum state is a configuration of quantum fields representing a local minimum but not global minimum of energy. This type of vacuum state is called a "false vacuum".

Implications

[edit]Existential threat

[edit]If our universe is in a false vacuum state rather than a true vacuum state, then the decay from the less stable false vacuum to the more stable true vacuum (called false vacuum decay) could have dramatic consequences.[5][6] The effects could range from complete cessation of existing fundamental forces, elementary particles and structures comprising them, to subtle change in some cosmological parameters, mostly depending on the potential difference between true and false vacuum. Some false vacuum decay scenarios are compatible with the survival of structures like galaxies, stars,[7][8] and even biological life,[9] while others involve the full destruction of baryonic matter[10] or even immediate gravitational collapse of the universe.[11] In this more extreme case, the likelihood of a "bubble" forming is very low (i.e. false vacuum decay may be impossible).[12]

A paper by Coleman and de Luccia that attempted to include simple gravitational assumptions into these theories noted that if this was an accurate representation of nature, then the resulting universe "inside the bubble" in such a case would appear to be extremely unstable and would almost immediately collapse:

In general, gravitation makes the probability of vacuum decay smaller; in the extreme case of very small energy-density difference, it can even stabilize the false vacuum, preventing vacuum decay altogether. We believe we understand this. For the vacuum to decay, it must be possible to build a bubble of total energy zero. In the absence of gravitation, this is no problem, no matter how small the energy-density difference; all one has to do is make the bubble big enough, and the volume/surface ratio will do the job. In the presence of gravitation, though, the negative energy density of the true vacuum distorts geometry within the bubble with the result that, for a small enough energy density, there is no bubble with a big enough volume/surface ratio. Within the bubble, the effects of gravitation are more dramatic. The geometry of space-time within the bubble is that of anti-de Sitter space, a space much like conventional de Sitter space except that its group of symmetries is O(3, 2) rather than O(4, 1). Although this space-time is free of singularities, it is unstable under small perturbations, and inevitably suffers gravitational collapse of the same sort as the end state of a contracting Friedmann universe. The time required for the collapse of the interior universe is on the order of ... microseconds or less.

The possibility that we are living in a false vacuum has never been a cheering one to contemplate. Vacuum decay is the ultimate ecological catastrophe; in the new vacuum there are new constants of nature; after vacuum decay, not only is life as we know it impossible, so is chemistry as we know it. Nonetheless, one could always draw stoic comfort from the possibility that perhaps in the course of time the new vacuum would sustain, if not life as we know it, at least some structures capable of knowing joy. This possibility has now been eliminated.

The second special case is decay into a space of vanishing cosmological constant, the case that applies if we are now living in the debris of a false vacuum that decayed at some early cosmic epoch. This case presents us with less interesting physics and with fewer occasions for rhetorical excess than the preceding one. It is now the interior of the bubble that is ordinary Minkowski space ...

— Sidney Coleman and Frank De Luccia[11]

In a 2005 paper published in Nature, as part of their investigation into global catastrophic risks, MIT physicist Max Tegmark and Oxford philosopher Nick Bostrom calculate the natural risks of the destruction of the Earth at less than 1/109 per year from all natural (i.e. non-anthropogenic) events, including a transition to a lower vacuum state. They argue that due to observer selection effects, we might underestimate the chances of being destroyed by vacuum decay because any information about this event would reach us only at the instant when we too were destroyed. This is in contrast to events like risks from impacts, gamma-ray bursts, supernovae and hypernovae, the frequencies of which we have adequate direct measures.[13]

Inflation

[edit]A number of theories suggest that cosmic inflation may be an effect of a false vacuum decaying into the true vacuum. The inflation itself may be the consequence of the Higgs field trapped in a false vacuum state[14] with Higgs self-coupling λ and its βλ function very close to zero at the planck scale.[15]: 218 A future electron-positron collider would be able to provide the precise measurements of the top quark needed for such calculations.[15]

Chaotic inflation theory suggests that the universe may be in either a false vacuum or a true vacuum state. Alan Guth, in his original proposal for cosmic inflation,[16] proposed that inflation could end through quantum mechanical bubble nucleation of the sort described above. See history of Chaotic inflation theory. It was soon understood that a homogeneous and isotropic universe could not be preserved through the violent tunneling process. This led Andrei Linde[17] and, independently, Andreas Albrecht and Paul Steinhardt,[18] to propose "new inflation" or "slow roll inflation" in which no tunnelling occurs, and the inflationary scalar field instead graphs as a gentle slope.

In 2014, researchers at the Chinese Academy of Sciences' Wuhan Institute of Physics and Mathematics suggested that the universe could have been spontaneously created from nothing (no space, time, nor matter) by quantum fluctuations of a metastable false vacuum causing an expanding bubble of true vacuum.[19]

Vacuum decay varieties

[edit]Electroweak vacuum decay

[edit]

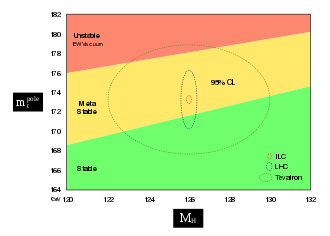

The stability criteria for the electroweak interaction was first formulated in 1979[20] as a function of the masses of the theoretical Higgs boson and the heaviest fermion. Discovery of the top quark in 1995 and the Higgs boson in 2012 have allowed physicists to validate the criteria against experiment, therefore since 2012 the electroweak interaction is considered as the most promising candidate for a metastable fundamental force.[15] The corresponding false vacuum hypothesis is called either "Electroweak vacuum instability" or "Higgs vacuum instability".[21] The present false vacuum state is called (de Sitter space), while tentative true vacuum is called (Anti-de Sitter space).[22][23]

The diagrams show the uncertainty ranges of Higgs boson and top quark masses as oval-shaped lines. Underlying colors indicate if the electroweak vacuum state is likely to be stable, merely long-lived or completely unstable for given combination of masses.[24][25] The "electroweak vacuum decay" hypothesis was sometimes misreported as the Higgs boson "ending" the universe.[26][27][28] A 125.18±0.16 GeV/c2 [29] Higgs boson mass is likely to be on the metastable side of stable-metastable boundary (estimated in 2012 as 123.8–135.0 GeV.[15]) A definitive answer requires much more precise measurements of the top quark's pole mass,[15] however, although improved measurement precision of Higgs boson and top quark masses further reinforced the claim of physical electroweak vacuum being in the metastable state as of 2018.[4] Nonetheless, new physics beyond the Standard Model of Particle Physics could drastically change the stability landscape division lines, rendering previous stability and metastability criteria incorrect.[30][31] Reanalysis of 2016 LHC run data in 2022 has yielded a slightly lower top quark mass of 171.77±0.38 GeV, close to vacuum stability line but still in the metastable zone.[32][33]

If measurements of the Higgs boson and top quark suggest that our universe lies within a false vacuum of this kind, this would imply that the bubble's effects will propagate across the universe at nearly the speed of light from its origin in space-time.[34] A direct calculation within the Standard Model of the lifetime of our vacuum state finds that it is greater than years with 95% confidence.[35]

Other decay modes

[edit]- Decay to smaller vacuum expectation value, resulting in decrease of Casimir effect and destabilization of proton.[10]

- Decay to vacuum with larger neutrino mass (may have happened as late as few billion years ago).[7]

- Decay to vacuum with no dark energy.[8]

- Decay of the false vacuum at finite temperature[36] was first observed in ferromagnetic superfluids of ultracold atoms.[37]

Bubble nucleation

[edit]When the false vacuum decays, the lower-energy true vacuum forms through a process known as bubble nucleation.[38][39][40][41][42][3] In this process, instanton effects cause a bubble containing the true vacuum to appear. The walls of the bubble (or domain walls) have a positive surface tension, as energy is expended as the fields roll over the potential barrier to the true vacuum. The former tends as the cube of the bubble's radius while the latter is proportional to the square of its radius, so there is a critical size at which the total energy of the bubble is zero; smaller bubbles tend to shrink, while larger bubbles tend to grow. To be able to nucleate, the bubble must overcome an energy barrier of height[3]

| (Eq. 1) |

where is the difference in energy between the true and false vacuums, is the unknown (possibly extremely large) surface tension of the domain wall, and is the radius of the bubble. Rewriting Eq. 1 gives the critical radius as

| (Eq. 2) |

A bubble smaller than the critical size can overcome the potential barrier via quantum tunnelling of instantons to lower energy states. For a large potential barrier, the tunneling rate per unit volume of space is given by[43]

| (Eq. 3) |

where is the reduced Planck constant. As soon as a bubble of lower-energy vacuum grows beyond the critical radius defined by Eq. 2, the bubble's wall will begin to accelerate outward. Due to the typically large difference in energy between the false and true vacuums, the speed of the wall approaches the speed of light extremely quickly. The bubble does not produce any gravitational effects because the negative energy density of the bubble interior is cancelled out by the positive kinetic energy of the wall.[11]

Small bubbles of true vacuum can be inflated to critical size by providing energy,[44] although required energy densities are several orders of magnitude larger than what is attained in any natural or artificial process.[10] It is also thought that certain environments can catalyze bubble formation by lowering the potential barrier.[45]

Bubble wall has a finite thickness, depending on ratio between energy barrier and energy gain obtained by creating true vacuum. In the case when potential barrier height between true and false vacua is much smaller than energy difference between vacua, shell thickness become comparable with critical radius.[46]

Nucleation seeds

[edit]In general, gravity is believed to stabilize a false vacuum state,[47] at least for transition from (de Sitter space) to (Anti-de Sitter space),[48] while topological defects including cosmic strings[49] and magnetic monopoles may enhance decay probability.[10]

Black holes as nucleation seeds

[edit]In a study in 2015,[45] it was pointed out that the vacuum decay rate could be vastly increased in the vicinity of black holes, which would serve as a nucleation seed.[50] According to this study, a potentially catastrophic vacuum decay could be triggered at any time by primordial black holes, should they exist. The authors note, however, that if primordial black holes cause a false vacuum collapse, then it should have happened long before humans evolved on Earth. A subsequent study in 2017 indicated that the bubble would collapse into a primordial black hole rather than originate from it, either by ordinary collapse or by bending space in such a way that it breaks off into a new universe.[51] In 2019, it was found that although small non-spinning black holes may increase true vacuum nucleation rate, rapidly spinning black holes will stabilize false vacuums to decay rates lower than expected for flat space-time.[52][53]

If particle collisions produce mini black holes, then energetic collisions such as the ones produced in the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) could trigger such a vacuum decay event, a scenario that has attracted the attention of the news media. It is likely to be unrealistic, because if such mini black holes can be created in collisions, they would also be created in the much more energetic collisions of cosmic radiation particles with planetary surfaces or during the early life of the universe as tentative primordial black holes.[54] Hut and Rees[55] note that, because cosmic ray collisions have been observed at much higher energies than those produced in terrestrial particle accelerators, these experiments should not, at least for the foreseeable future, pose a threat to our current vacuum. Particle accelerators have reached energies of only approximately eight tera electron volts (8×1012 eV). Cosmic ray collisions have been observed at and beyond energies of 5×1019 eV, six million times more powerful – the so-called Greisen–Zatsepin–Kuzmin limit – and cosmic rays in vicinity of origin may be more powerful yet. John Leslie has argued[56] that if present trends continue, particle accelerators will exceed the energy given off in naturally occurring cosmic ray collisions by the year 2150. Fears of this kind were raised by critics of both the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider and the Large Hadron Collider at the time of their respective proposal, and determined to be unfounded by scientific inquiry.

In a 2021 paper by Rostislav Konoplich and others, it was postulated that the area between a pair of large black holes on the verge of colliding could provide the conditions to create bubbles of "true vacuum". Intersecting surfaces between these bubbles could then become infinitely dense and form micro-black holes. These would in turn evaporate by emitting Hawking radiation in the 10 milliseconds or so before the larger black holes collided and devoured any bubbles or micro-black holes in their way. The theory could be tested by looking for the Hawking radiation emitted just before the black holes merge.[57][58]

Bubble propagation

[edit]A bubble wall, propagating outward at nearly the speed of light, has a finite thickness, depending on the ratio between the energy barrier and the energy gain obtained by creating true vacuum. In the case when the potential barrier height between true and false vacua is much smaller than the energy difference between vacua, the bubble wall thickness becomes comparable to the critical radius.[46]

Elementary particles entering the wall will likely decay to other particles or black holes. If all decay paths lead to very massive particles, the energy barrier of such a decay may result in a stable bubble of false vacuum (also known as a Fermi ball) enclosing the false-vacuum particle instead of immediate decay. Multi-particle objects can be stabilized as Q-balls, although these objects will eventually collide and decay either into black holes or true-vacuum particles.[59]

False vacuum decay in fiction

[edit]False vacuum decay event is occasionally used as a plot device in works picturing a doomsday event.

- 1988 by Geoffrey A. Landis in his science-fiction short story Vacuum States[60]

- 2000 by Stephen Baxter in his science fiction novel Time[61]

- 2002 by Greg Egan in his science fiction novel Schild's Ladder

- 2002 by Liu Cixin in his science fiction novel Zhao Wen Dao

- 2008 by Koji Suzuki in his science fiction novel Edge

- 2015 by Alastair Reynolds in his science fiction novel Poseidon's Wake

- 2018 by System Erasure in their video game ZeroRanger

See also

[edit]- Eternal inflation – Hypothetical inflationary universe model

- Supercooling – Lowering the temperature of a liquid below its freezing point without it becoming a solid

- Superheating – Heating a liquid to a temperature above its boiling point without boiling

- Void – Vast empty spaces between filaments with few or no galaxies

- Quantum cosmology – Attempts to develop a quantum mechanical theory of cosmology

- Why is there anything at all?#Something may exist necessarily – Metaphysical question

References

[edit]- ^ Abel, Steven; Spannowsky, Michael (2021). "Quantum-Field-Theoretic Simulation Platform for Observing the Fate of the False Vacuum". PRX Quantum. 2: 010349. arXiv:2006.06003. doi:10.1103/PRXQuantum.2.010349. S2CID 234355374.

- ^ "Vacuum decay: the ultimate catastrophe". Cosmos Magazine. 2015-09-13. Retrieved 2020-09-16.

- ^ a b c C. Callan; S. Coleman (1977). "Fate of the false vacuum. II. First quantum corrections". Physical Review D. D16 (6): 1762–68. Bibcode:1977PhRvD..16.1762C. doi:10.1103/physrevd.16.1762.

- ^ a b c Markkanen, Tommi; Rajantie, Arttu; Stopyra, Stephen (2018). "Cosmological Aspects of Higgs Vacuum Metastability". Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences. 5: 40. arXiv:1809.06923. Bibcode:2018FrASS...5...40R. doi:10.3389/fspas.2018.00040. S2CID 56482474.

- ^ "How 'vacuum decay' could end the universe - Big Think". January 2019.

- ^ "Vacuum decay: the ultimate catastrophe". 14 September 2015.

- ^ a b Lorenz, Christiane S.; Funcke, Lena; Calabrese, Erminia; Hannestad, Steen (2019). "Time-varying neutrino mass from a supercooled phase transition: Current cosmological constraints and impact on the Ωm−σ8 plane". Physical Review D. 99 (2): 023501. arXiv:1811.01991. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.99.023501. S2CID 119344201.

- ^ a b Landim, Ricardo G.; Abdalla, Elcio (2017). "Metastable dark energy". Physics Letters B. 764: 271–276. arXiv:1611.00428. Bibcode:2017PhLB..764..271L. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2016.11.044. S2CID 119279028.

- ^ Crone, Mary M.; Sher, Marc (1991). "The environmental impact of vacuum decay". American Journal of Physics. 59 (1): 25. Bibcode:1991AmJPh..59...25C. doi:10.1119/1.16701.

- ^ a b c d Turner, M. S.; Wilczek, F. (1982-08-12). "Is our vacuum metastable?" (PDF). Nature. 298 (5875): 633–634. Bibcode:1982Natur.298..633T. doi:10.1038/298633a0. S2CID 4274444. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 December 2019. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- ^ a b c Coleman, Sidney; De Luccia, Frank (1980-06-15). "Gravitational effects on and of vacuum decay" (PDF). Physical Review D. 21 (12): 3305–3315. Bibcode:1980PhRvD..21.3305C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.21.3305. OSTI 1445512. S2CID 1340683. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 December 2019. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- ^ Banks, T. (2002). "Heretics of the False Vacuum: Gravitational Effects on and of Vacuum Decay 2". arXiv:hep-th/0211160.

- ^ Tegmark, M.; Bostrom, N. (2005). "Is a doomsday catastrophe likely?" (PDF). Nature. 438 (5875): 754. Bibcode:2005Natur.438..754T. doi:10.1038/438754a. PMID 16341005. S2CID 4390013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-04-09. Retrieved 2016-03-16.

- ^ Smeenk, Chris. "False Vacuum: Early Universe Cosmology and the Development of Inflation" (PDF).

- ^ a b c d e f Alekhin, S.; Djouadi, A.; Moch, S.; Hoecker, A.; Riotto, A. (2012-08-13). "The top quark and Higgs boson masses and the stability of the electroweak vacuum". Physics Letters B. 716 (1): 214–219. arXiv:1207.0980. Bibcode:2012PhLB..716..214A. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2012.08.024. S2CID 28216028.

- ^ Guth, Allan H. (1981-01-15). "The Inflationary Universe: A Possible Solution to the Horizon and Flatness Problems". Physical Review D. 23 (2): 347–356. Bibcode:1981PhRvD..23..347G. doi:10.1103/physrevd.23.347. OCLC 4433735058.

- ^ Linde, Andrei (1982). "A New Inflationary Universe Scenario: A Possible Solution Of The Horizon, Flatness, Homogeneity, Isotropy And Primordial Monopole Problems". Phys. Lett. B. 108 (6): 389. Bibcode:1982PhLB..108..389L. doi:10.1016/0370-2693(82)91219-9.

- ^ Albrecht, A.; Steinhardt, P. J. (1982). "Cosmology For Grand Unified Theories With Radiatively Induced Symmetry Breaking". Physical Review Letters. 48 (17): 1220–1223. Bibcode:1982PhRvL..48.1220A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.48.1220.

- ^ He, Dongshan; Gao, Dongfeng; Cai, Qing-yu (2014). "Spontaneous creation of the universe from nothing". Physical Review D. 89 (8): 083510. arXiv:1404.1207. Bibcode:2014PhRvD..89h3510H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.89.083510. S2CID 118371273.

- ^ N. Cabibbo; L. Maiani; G. Parisi; R. Petronzio (1979). "Bounds on the Fermions and Higgs Boson Masses in Grand Unified Theories" (PDF).

- ^ Kohri, Kazunori; Matsui, Hiroki (2018). "Electroweak vacuum instability and renormalized vacuum field fluctuations in Friedmann-Lemaitre-Robertson-Walker background". Physical Review D. 98 (10): 103521. arXiv:1704.06884. Bibcode:2018PhRvD..98j3521K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.98.103521. S2CID 39999058.

- ^ Hook, Anson; Kearney, John; Shakya, Bibhushan; Zurek, Kathryn M. (2015). "Probable or improbable universe? Correlating electroweak vacuum instability with the scale of inflation". Journal of High Energy Physics. 2015 (1): 61. arXiv:1404.5953. Bibcode:2015JHEP...01..061H. doi:10.1007/JHEP01(2015)061. S2CID 118737905.

- ^ Kohri, Kazunori; Matsui, Hiroki (2017). "Electroweak vacuum instability and renormalized Higgs field vacuum fluctuations in the inflationary universe". Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics. 2017 (8): 011. arXiv:1607.08133. Bibcode:2017JCAP...08..011K. doi:10.1088/1475-7516/2017/08/011. S2CID 119216421.

- ^ Ellis, J.; Espinosa, J. R.; Giudice, G. F.; Hoecker, A.; Riotto, A. (2009). "The Probable Fate of the Standard Model". Phys. Lett. B. 679 (4): 369–375. arXiv:0906.0954. Bibcode:2009PhLB..679..369E. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2009.07.054. S2CID 17422678.

- ^ Masina, Isabella (2013-02-12). "Higgs boson and top quark masses as tests of electroweak vacuum stability". Physical Review D. 87 (5): 053001. arXiv:1209.0393. Bibcode:2013PhRvD..87e3001M. doi:10.1103/physrevd.87.053001. S2CID 118451972.

- ^ Klotz, Irene (18 February 2013). Adams, David; Eastham, Todd (eds.). "Universe has finite lifespan, Higgs boson calculations suggest". Huffington Post. Reuters. Archived from the original on 20 February 2013. Retrieved 21 February 2013.

Earth will likely be long gone before any Higgs boson particles set off an apocalyptic assault on the universe

- ^ Hoffman, Mark (19 February 2013). "Higgs boson will destroy the universe, eventually". Science World Report. Archived from the original on 11 June 2019. Retrieved 21 February 2013.

- ^ "Higgs boson will aid in creation of the universe—and how it will end". Catholic Online/NEWS CONSORTIUM. 2013-02-20. Archived from the original on 26 September 2013. Retrieved 21 February 2013.

- ^ Tanabashi, M.; et al. (2018). "Review of Particle Physics". Physical Review D. 98 (3): 1–708. Bibcode:2018PhRvD..98c0001T. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.98.030001. hdl:10044/1/68623. PMID 10020536.

- ^ Salvio, Alberto (2015-04-09). "A Simple Motivated Completion of the Standard Model below the Planck Scale: Axions and Right-Handed Neutrinos". Physics Letters B. 743: 428–434. arXiv:1501.03781. Bibcode:2015PhLB..743..428S. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2015.03.015. S2CID 119279576.

- ^ Branchina, Vincenzo; Messina, Emanuele; Platania, Alessia (2014). "Top mass determination, Higgs inflation, and vacuum stability". Journal of High Energy Physics. 2014 (9): 182. arXiv:1407.4112. Bibcode:2014JHEP...09..182B. doi:10.1007/JHEP09(2014)182. S2CID 102338312.

- ^ Vanadia, Marco (2022), Direct top quark mass measurements with the ATLAS and CMS detectors, arXiv:2211.11398

- ^ Collaboration, CMS (2023). "Measurement of the top quark mass using a profile likelihood approach with the lepton + jets final states in proton–proton collisions at ". The European Physical Journal C. 83 (10): 963. arXiv:2302.01967. doi:10.1140/epjc/s10052-023-12050-4. PMC 10600315. PMID 37906635. S2CID 264442852.

- ^ Boyle, Alan (19 February 2013). "Will our universe end in a 'big slurp'? Higgs-like particle suggests it might". NBC News' Cosmic blog. Archived from the original on 21 February 2013. Retrieved 21 February 2013.

[T]he bad news is that its mass suggests the universe will end in a fast-spreading bubble of doom. The good news? It'll probably be tens of billions of years.

The article quotes Fermilab's Joseph Lykken: "[T]he parameters for our universe, including the Higgs [and top quark's masses] suggest that we're just at the edge of stability, in a "metastable" state. Physicists have been contemplating such a possibility for more than 30 years. Back in 1982, physicists Michael Turner and Frank Wilczek wrote in Nature that "without warning, a bubble of true vacuum could nucleate somewhere in the universe and move outwards ..." - ^ Andreassen, Anders; Frost, William; Schwartz, Matthew D. (2018). "Scale Invariant Instantons and the Complete Lifetime of the Standard Model". Physical Review D. 97 (5): 056006. arXiv:1707.08124. Bibcode:2018PhRvD..97e6006A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.97.056006. S2CID 118843387.

- ^ Linde, Andrei D. (1983). "Decay of the false vacuum at finite temperature". Nucl. Phys. B. 216 (2): 421–445. Bibcode:1983NuPhB.216..421L. doi:10.1016/0550-3213(83)90293-6.

- ^ Zenesini, Alessandro; Berti, Anna; Cominotti, Riccardo; Rogora, Chiara; Moss, Ian G.; Billam, Tom P.; Carusotto, Iacopo; Lamporesi, Giacomo; Recati, Alessio; Ferrari, Gabriele (2024). "False vacuum decay via bubble formation in ferromagnetic superfluids". Nat. Phys. 10 (4): 558–563. arXiv:2305.05225. Bibcode:2024NatPh..20..558Z. doi:10.1038/s41567-023-02345-4.

- ^ Stone, M. (1976). "Lifetime and decay of excited vacuum states". Physical Review D. 14 (12): 3568–3573. Bibcode:1976PhRvD..14.3568S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.14.3568.

- ^ Frampton, P. H. (1976). "Vacuum Instability and Higgs Scalar Mass". Physical Review Letters. 37 (21): 1378–1380. Bibcode:1976PhRvL..37.1378F. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.37.1378.

- ^ Stone, M. (1977). "Semiclassical methods for unstable states". Phys. Lett. B. 67 (2): 186–188. Bibcode:1977PhLB...67..186S. doi:10.1016/0370-2693(77)90099-5.

- ^ Frampton, P. H. (1977). "Consequences of Vacuum Instability in Quantum Field Theory". Physical Review D. 15 (10): 2922–28. Bibcode:1977PhRvD..15.2922F. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.15.2922.

- ^ Coleman, S. (1977). "Fate of the false vacuum: Semiclassical theory". Physical Review D. 15 (10): 2929–36. Bibcode:1977PhRvD..15.2929C. doi:10.1103/physrevd.15.2929.

- ^ Ai, Wenyuan (2019). "Aspects of False Vacuum Decay" (PDF).

- ^ Arnold, Peter (1992). "A Review of the Instability of Hot Electroweak Theory and its Bounds on mh and mt". arXiv:hep-ph/9212303.

- ^ a b Burda, Philipp; Gregory, Ruth; Moss, Ian G. (2015). "Vacuum metastability with black holes". Journal of High Energy Physics. 2015 (8): 114. arXiv:1503.07331. Bibcode:2015JHEP...08..114B. doi:10.1007/JHEP08(2015)114. ISSN 1029-8479. S2CID 53978709.

- ^ a b Mukhanov, V. F.; Sorin, A. S. (2022), "Instantons: Thick-wall approximation", Journal of High Energy Physics, 2022 (7): 147, arXiv:2206.13994, Bibcode:2022JHEP...07..147M, doi:10.1007/JHEP07(2022)147, S2CID 250088782

- ^ Devoto, Federica; Devoto, Simone; Di Luzio, Luca; Ridolfi, Giovanni (2022), "False vacuum decay: An introductory review", Journal of Physics G: Nuclear and Particle Physics, 49 (10): 83, arXiv:2205.03140, Bibcode:2022JPhG...49j3001D, doi:10.1088/1361-6471/ac7f24, S2CID 248563024

- ^ Espinosa, J. R.; Fortin, J.-F.; Huertas, J. (2021), "Exactly solvable vacuum decays with gravity", Physical Review D, 104 (6): 20, arXiv:2106.15505, Bibcode:2021PhRvD.104f5007E, doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.104.065007, S2CID 235669653

- ^ Firouzjahi, Hassan; Karami, Asieh; Rostami, Tahereh (2020). "Vacuum decay in the presence of a cosmic string". Physical Review D. 101 (10): 104036. arXiv:2002.04856. Bibcode:2020PhRvD.101j4036F. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.101.104036. S2CID 211082988.

- ^ "Could Black Holes Destroy the Universe?". 2015-04-02.

- ^ Deng, Heling; Vilenkin, Alexander (2017). "Primordial black hole formation by vacuum bubbles". Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics. 2017 (12): 044. arXiv:1710.02865. Bibcode:2017JCAP...12..044D. doi:10.1088/1475-7516/2017/12/044. S2CID 119442566.

- ^ Oshita, Naritaka; Ueda, Kazushige; Yamaguchi, Masahide (2020). "Vacuum decays around spinning black holes". Journal of High Energy Physics. 2020 (1): 015. arXiv:1909.01378. Bibcode:2020JHEP...01..015O. doi:10.1007/JHEP01(2020)015. S2CID 202541418.

- ^ Saito, Daiki; Yoo, Chul-Moon (2023), "Stationary vacuum bubble in a Kerr–de Sitter spacetime", Physical Review D, 107 (6): 064043, arXiv:2208.07504, Bibcode:2023PhRvD.107f4043S, doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.107.064043, S2CID 251589418

- ^ Cho, Adrian (2015-08-03). "Tiny black holes could trigger collapse of universe—except that they don't". Sciencemag.org.

- ^ Hut, P.; Rees, M. J. (1983). "How stable is our vacuum?". Nature. 302 (5908): 508–509. Bibcode:1983Natur.302..508H. doi:10.1038/302508a0. S2CID 4347886.

- ^ Leslie, John (1998). The End of the World:The Science and Ethics of Human Extinction. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-14043-0.

- ^ Crane, Leah (26 November 2021). "Merging black holes may create bubbles that could swallow the universe". New Scientist. Retrieved 2021-11-27.

- ^ Chitishvili, Mariam; Gogberashvili, Merab; Konoplich, Rostislav; Sakharov, Alexander S. (2023). "Higgs Field-Induced Triboluminescence in Binary Black Hole Mergers". Universe. 9 (7): 301. arXiv:2111.07178. Bibcode:2023Univ....9..301C. doi:10.3390/universe9070301.

- ^ Kawana, Kiyoharu; Lu, Philip; Xie, Ke-Pan (2022), "First-order phase transition and fate of false vacuum remnants", Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics, 2022 (10): 030, arXiv:2206.09923, Bibcode:2022JCAP...10..030K, doi:10.1088/1475-7516/2022/10/030, S2CID 249889432

- ^ Landis, Geoffrey A. (1988). "Vacuum States". Isaac Asimov's Science Fiction: July.

- ^ Baxter, Stephen (2000). Time. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-7653-1238-9.

Further reading

[edit]- Johann Rafelski and Berndt Muller (1985). The Structured Vacuum – thinking about nothing. Harri Deutsch. ISBN 978-3-87144-889-8.

- Sidney Coleman (1988). Aspects of Symmetry: Selected Erice Lectures. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-31827-3.

External links

[edit]- SimpleBounce on GitHub calculates the Euclidean action for the bounce solution that contributes to the false vacuum decay.

- Rafelski, Johann; Müller, Berndt (1985). The Structured Vacuum – thinking about nothing (PDF). H. Deutsch. ISBN 3-87144-889-3.

- Guth, Alan. "An eternity of bubbles?". PBS. Archived from the original on 2012-08-25.

- Simulation of False Vacuum Decay by Bubble Nucleation on YouTube – Joel Thorarinson.