Neuropilin 1

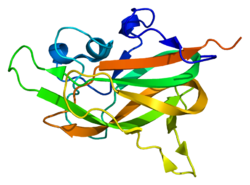

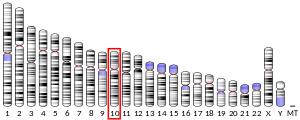

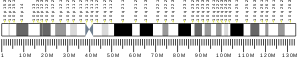

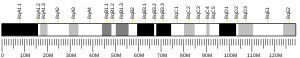

Neuropilin-1 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the NRP1 gene.[5][6][7] In humans, the neuropilin 1 gene is located at 10p11.22. This is one of two human neuropilins.

Function

[edit]NRP1 is a membrane-bound coreceptor to a tyrosine kinase receptor for both vascular endothelial growth factor (for example, VEGFA) and semaphorin (for example, SEMA3A) family members. NRP1 plays versatile roles in angiogenesis, axon guidance, cell survival, migration, and invasion.[supplied by OMIM][7]

Interactions

[edit]Neuropilin 1 has been shown to interact with Vascular endothelial growth factor A.[5][8]

Role in COVID-19

[edit]Research has shown that neuropilin 1 facilitates entry of SARS-CoV-2 into cells, making it a possible target for future antiviral drugs.[9][10]

Implication in cancer

[edit]Neuropilin 1 has been implicated in the vascularization and progression of cancers. NRP1 expression has been shown to be elevated in a number of human patient tumor samples, including brain, prostate, breast, colon, and lung cancers and NRP1 levels are positively correlated with metastasis.[11][12][13][14][15][16]

In prostate cancer NRP1 has been demonstrated to be an androgen-suppressed gene, upregulated during the adaptive response of prostate tumors to androgen-targeted therapies and a prognostic biomarker of clinical metastasis and lethal PCa.[11] In vitro and in vivo mouse studies have shown membrane bound NRP1 to be proangiogenic and that NRP1 promotes the vascularization of prostate tumors.[17]

Elevated NRP1 expression is also correlated with the invasiveness of non-small cell lung cancer both in vitro and in vivo.[16]

Target for cancer therapies

[edit]As a co-receptor for VEGF, NRP1 is a potential target for cancer therapies. A synthetic peptide, EG3287, was generated in 2005 and has been shown to block NRP1 activity.[18] EG3287 has been shown to induce apoptosis in tumor cells with elevated NRP1 expression.[18] A patent for EG3287 was filed in 2002 and approved in 2003.[19] As of 2015 there were no clinical trials ongoing or completed for EG3287 as a human cancer therapy.

Soluble NRP1 has the opposite effect of membrane bound NRP1 and has anti-VEGF activity. In vivo mouse studies have shown that injections of sNRP-1 inhibits progression of acute myeloid leukemia in mice.[20]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000099250 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000025810 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ a b Soker S, Takashima S, Miao HQ, Neufeld G, Klagsbrun M (March 1998). "Neuropilin-1 is expressed by endothelial and tumor cells as an isoform-specific receptor for vascular endothelial growth factor". Cell. 92 (6): 735–745. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81402-6. PMID 9529250. S2CID 547080.

- ^ Chen H, Chédotal A, He Z, Goodman CS, Tessier-Lavigne M (September 1997). "Neuropilin-2, a novel member of the neuropilin family, is a high affinity receptor for the semaphorins Sema E and Sema IV but not Sema III". Neuron. 19 (3): 547–559. doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80371-2. PMID 9331348. S2CID 17985062.

- ^ a b "Entrez Gene: NRP1 neuropilin 1".

- ^ Mamluk R, Gechtman Z, Kutcher ME, Gasiunas N, Gallagher J, Klagsbrun M (July 2002). "Neuropilin-1 binds vascular endothelial growth factor 165, placenta growth factor-2, and heparin via its b1b2 domain". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (27): 24818–24825. doi:10.1074/jbc.M200730200. PMID 11986311.

- ^ Cantuti-Castelvetri L, Ojha R, Pedro LD, Djannatian M, Franz J, Kuivanen S, et al. (November 2020). "Neuropilin-1 facilitates SARS-CoV-2 cell entry and infectivity". Science. 370 (6518): 856–860. Bibcode:2020Sci...370..856C. doi:10.1126/science.abd2985. PMC 7857391. PMID 33082293.

- ^ "Neuropilin-1 drives SARS-CoV-2 infectivity, finds breakthrough study". MedicalXpress.

- ^ a b Tse BW, Volpert M, Ratther E, Stylianou N, Nouri M, McGowan K, et al. (June 2017). "Neuropilin-1 is upregulated in the adaptive response of prostate tumors to androgen-targeted therapies and is prognostic of metastatic progression and patient mortality". Oncogene. 36 (24): 3417–3427. doi:10.1038/onc.2016.482. PMC 5485179. PMID 28092670.

- ^ Fakhari M, Pullirsch D, Abraham D, Paya K, Hofbauer R, Holzfeind P, et al. (January 2002). "Selective upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptors neuropilin-1 and -2 in human neuroblastoma". Cancer. 94 (1): 258–263. doi:10.1002/cncr.10177. PMID 11815985. S2CID 45773136.

- ^ Latil A, Bièche I, Pesche S, Valéri A, Fournier G, Cussenot O, et al. (March 2000). "VEGF overexpression in clinically localized prostate tumors and neuropilin-1 overexpression in metastatic forms". International Journal of Cancer. 89 (2): 167–171. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(20000320)89:2<167::AID-IJC11>3.0.CO;2-9. PMID 10754495. S2CID 7393385.

- ^ Bachelder RE, Crago A, Chung J, Wendt MA, Shaw LM, Robinson G, et al. (August 2001). "Vascular endothelial growth factor is an autocrine survival factor for neuropilin-expressing breast carcinoma cells". Cancer Research. 61 (15): 5736–5740. PMID 11479209.

- ^ Parikh AA, Fan F, Liu WB, Ahmad SA, Stoeltzing O, Reinmuth N, et al. (June 2004). "Neuropilin-1 in human colon cancer: expression, regulation, and role in induction of angiogenesis". The American Journal of Pathology. 164 (6): 2139–2151. doi:10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63772-8. PMC 1615754. PMID 15161648.

- ^ a b Hong TM, Chen YL, Wu YY, Yuan A, Chao YC, Chung YC, et al. (August 2007). "Targeting neuropilin 1 as an antitumor strategy in lung cancer". Clinical Cancer Research. 13 (16): 4759–4768. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0001. PMID 17699853.

- ^ Miao HQ, Lee P, Lin H, Soker S, Klagsbrun M (December 2000). "Neuropilin-1 expression by tumor cells promotes tumor angiogenesis and progression". FASEB Journal. 14 (15): 2532–2539. doi:10.1096/fj.00-0250com. PMID 11099472. S2CID 2370002.

- ^ a b Barr MP, Byrne AM, Duffy AM, Condron CM, Devocelle M, Harriott P, et al. (January 2005). "A peptide corresponding to the neuropilin-1-binding site on VEGF(165) induces apoptosis of neuropilin-1-expressing breast tumour cells". British Journal of Cancer. 92 (2): 328–333. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6602308. PMC 2361857. PMID 15655556.

- ^ "Vegf peptides and their use (WO 2003082918 A1)" (patent). Oct 9, 2003.

- ^ Gagnon ML, Bielenberg DR, Gechtman Z, Miao HQ, Takashima S, Soker S, et al. (March 2000). "Identification of a natural soluble neuropilin-1 that binds vascular endothelial growth factor: In vivo expression and antitumor activity". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 97 (6): 2573–2578. Bibcode:2000PNAS...97.2573G. doi:10.1073/pnas.040337597. PMC 15970. PMID 10688880.

Further reading

[edit]- Zachary I, Gliki G (February 2001). "Signaling transduction mechanisms mediating biological actions of the vascular endothelial growth factor family". Cardiovascular Research. 49 (3): 568–581. doi:10.1016/S0008-6363(00)00268-6. PMID 11166270.

- He Z, Tessier-Lavigne M (August 1997). "Neuropilin is a receptor for the axonal chemorepellent Semaphorin III". Cell. 90 (4): 739–751. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80534-6. PMID 9288753. S2CID 9720408.

- Giger RJ, Urquhart ER, Gillespie SK, Levengood DV, Ginty DD, Kolodkin AL (November 1998). "Neuropilin-2 is a receptor for semaphorin IV: insight into the structural basis of receptor function and specificity". Neuron. 21 (5): 1079–1092. doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80625-X. PMID 9856463. S2CID 18445456.

- Chen H, He Z, Bagri A, Tessier-Lavigne M (December 1998). "Semaphorin-neuropilin interactions underlying sympathetic axon responses to class III semaphorins". Neuron. 21 (6): 1283–1290. doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80648-0. PMID 9883722.

- Takahashi T, Nakamura F, Jin Z, Kalb RG, Strittmatter SM (October 1998). "Semaphorins A and E act as antagonists of neuropilin-1 and agonists of neuropilin-2 receptors". Nature Neuroscience. 1 (6): 487–493. doi:10.1038/2203. PMID 10196546. S2CID 38320889.

- Rossignol M, Beggs AH, Pierce EA, Klagsbrun M (May 1999). "Human neuropilin-1 and neuropilin-2 map to 10p12 and 2q34, respectively". Genomics. 57 (3): 459–460. doi:10.1006/geno.1999.5790. PMID 10329017.

- Makinen T, Olofsson B, Karpanen T, Hellman U, Soker S, Klagsbrun M, et al. (July 1999). "Differential binding of vascular endothelial growth factor B splice and proteolytic isoforms to neuropilin-1". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 274 (30): 21217–21222. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.30.21217. PMID 10409677.

- Cai H, Reed RR (August 1999). "Cloning and characterization of neuropilin-1-interacting protein: a PSD-95/Dlg/ZO-1 domain-containing protein that interacts with the cytoplasmic domain of neuropilin-1". The Journal of Neuroscience. 19 (15): 6519–6527. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-15-06519.1999. PMC 6782790. PMID 10414980.

- Takahashi T, Fournier A, Nakamura F, Wang LH, Murakami Y, Kalb RG, et al. (October 1999). "Plexin-neuropilin-1 complexes form functional semaphorin-3A receptors". Cell. 99 (1): 59–69. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80062-8. PMID 10520994. S2CID 18167425.

- Tamagnone L, Artigiani S, Chen H, He Z, Ming GI, Song H, et al. (October 1999). "Plexins are a large family of receptors for transmembrane, secreted, and GPI-anchored semaphorins in vertebrates". Cell. 99 (1): 71–80. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80063-X. PMID 10520995. S2CID 17386412.

- Gagnon ML, Bielenberg DR, Gechtman Z, Miao HQ, Takashima S, Soker S, et al. (March 2000). "Identification of a natural soluble neuropilin-1 that binds vascular endothelial growth factor: In vivo expression and antitumor activity". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 97 (6): 2573–2578. Bibcode:2000PNAS...97.2573G. doi:10.1073/pnas.040337597. PMC 15970. PMID 10688880.

- Gluzman-Poltorak Z, Cohen T, Herzog Y, Neufeld G (June 2000). "Neuropilin-2 is a receptor for the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) forms VEGF-145 and VEGF-165 [corrected]". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 275 (24): 18040–18045. doi:10.1074/jbc.M909259199. PMID 10748121.

- Fuh G, Garcia KC, de Vos AM (September 2000). "The interaction of neuropilin-1 with vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptor flt-1". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 275 (35): 26690–26695. doi:10.1074/jbc.M003955200. PMID 10842181.

- Rossignol M, Gagnon ML, Klagsbrun M (December 2000). "Genomic organization of human neuropilin-1 and neuropilin-2 genes: identification and distribution of splice variants and soluble isoforms". Genomics. 70 (2): 211–222. doi:10.1006/geno.2000.6381. PMID 11112349.

- Simpson JC, Wellenreuther R, Poustka A, Pepperkok R, Wiemann S (September 2000). "Systematic subcellular localization of novel proteins identified by large-scale cDNA sequencing". EMBO Reports. 1 (3): 287–292. doi:10.1093/embo-reports/kvd058. PMC 1083732. PMID 11256614.

- Whitaker GB, Limberg BJ, Rosenbaum JS (July 2001). "Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 and neuropilin-1 form a receptor complex that is responsible for the differential signaling potency of VEGF(165) and VEGF(121)". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (27): 25520–25531. doi:10.1074/jbc.M102315200. PMID 11333271.

- Walter JW, North PE, Waner M, Mizeracki A, Blei F, Walker JW, et al. (March 2002). "Somatic mutation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptors in juvenile hemangioma". Genes, Chromosomes & Cancer. 33 (3): 295–303. doi:10.1002/gcc.10028. PMID 11807987. S2CID 33428561.