Uzumaki (film)

| Uzumaki | |

|---|---|

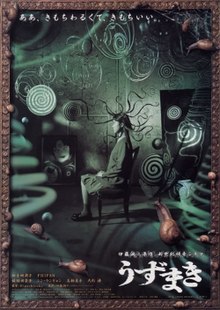

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Higuchinsky[1] |

| Screenplay by | Takao Niita[1][2] |

| Based on | Uzumaki by Junji Ito |

| Produced by | Sumiji Miyake[2] |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Gen Kobayashi[1] |

| Music by | |

Production company | Omega Micott[2] |

Release date |

|

Running time | 90 minutes |

| Country | Japan[2] |

| Language | Japanese |

Uzumaki (Japanese: うずまき, lit. "Spiral") is a 2000 Japanese supernatural horror film based on the manga of the same name by Junji Ito. The feature film directorial debut of Higuchinsky, it stars Eriko Hatsune, Fhi Fan, Hinako Saeki and Shin Eun-kyung. The film takes place in a town plagued by a mysterious curse involving spirals. As the film was produced while the manga was still being written and released, it departs from the story of the original work and features a different ending.

The film was backed by the company Omega Micott, who released it in Japan on a double bill with Tomie: Replay, another film based on a manga by Ito. Simultaneously, Uzumaki received a limited release in the American city of San Francisco. It received mixed reviews from critics.

Plot

[edit]High school student Kirie Goshima's first glimpse that something is awry in the small town of Kurouzu-cho comes when her boyfriend Shuichi Saito's father begins to film the corkscrew patterns on a snail; he is also in the process of making a video scrapbook filled with the images of anything that has a spiral or vortex shape to it. His unusual obsession causes him to abandon his responsibilities at work; he proclaims that a spiral is the highest form of art, and frantically creates whirlpools in his miso soup when he runs out of spiral-patterned kamaboko. He then decides to film himself crawling into a washing machine, where he dies.

It is not long before the entire town is infected by the otherworldly spirals. Tamura, a reporter, is intrigued by Shuichi's father's suicide and becomes obsessed with the case. Meanwhile, Shuichi's mother, who has been in hospital since her husband's death, has developed a severe phobia of spirals. She cuts off her hair and fingertips due to their spiral-like shapes, and Shuichi tells the hospital staff to eliminate anything spiral-shaped so his mother may not encounter them. One night, after a millipede tries to crawl into her ear while she is asleep, the millipede claims to be her husband and turns into a spiral, driving her to commit suicide.

Meanwhile, at Kirie's high school, a student named Katayama begins to walk at a snail's pace, dripping in a slimy substance and only attending school on rainy days. He and other members of the student body gradually begin to sprout shells, drink water in copious amounts, and crawl on the walls of the school. Kirie's classmate, Sekino, begins to grow her hair in exaggerated curls, taking over her mind and the minds of other female students. Whirl-like clouds appear in the sky, and during funerals, they are accompanied by smoky, ghost-like faces of victims who perished in spiral-related ways.

Eventually, the entire town succumbs to the curse of the spiral—Kirie's father takes a drill to his eye after obsessively creating spiral-shaped ceramics; a news crew reporting on the phenomenon lose themselves in a tunnel, only to be later found as humanoid yet snail-like corpses; and Sekino's snake-like curls grow to an abnormal height, wrapping around a telephone pole and cables electrocuting herself. A boy named Mitsuru, who is obsessed with Kirie, throws himself in front of Inspector Tamura's car and is twisted around the axle; the car collides with a pole, causing Tamura's head to hit the windshield, leaving a spiral-shaped crack. When Kirie and Shuichi decide to search for Kirie's father, Shuichi's body twists into a spiral-like contortion. He crawls towards Kirie, asking her to "become a spiral too". Refusing to let Shuichi back to his side, Kirie flees, and her fate is left unknown.

Cast

[edit]

- Eriko Hatsune as Kirie Goshima

- Fhi Fan as Shuichi Saito

- Hinako Saeki as Kyoko Sekino

- Shin Eun-kyung as Chie Maruyana

- Keiko Takahashi as Yukie Saito

- Ren Osugi as Toshio Saito

- Denden as Officer Futada

- Masami Horiuchi as Reporter Ichiro Tamura

- Taro Suwa as Yasuo Goshima

- Toru Tezuka as Yokota Ikuo

- Sadao Abe as Mitsuru Yamaguchi

- Asumi Miwa as Shiho Ishikawa

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]Uzumaki is based on the manga Uzumaki, written and illustrated by Junji Ito.[3] Ito had stated that for most of his stories, he starts with a visual image and builds a story around the picture.[4] For Uzumaki, he had a different inspiration of wanting to make a manga about people who lived in a traditional Japanese row-house and seeing what happened.[4] When drawing the row-houses, he found himself drawing a very long house that coiled into a spiral to fit on his page.[4]

The film was the debut feature for director Akihiro Higuchi, under his alias of Higuchinsky.[5][6] While filming the television series Eko Eko Azarak, director Higuchinsky met Kengo Kaji, to whom he proposed the idea of making a film.[7] Higuchinsky stated that he originally wanted to make a film like Star Wars but realized that "because I'm Japanese, I should do something different."[6]

Higuchinsky had been reading a manga magazine compilation which contained Ito's Uzumaki.[7] Higuchinsky thought the manga was brilliant and asked Kengo Kaji to adapt the film, finding out that the manga was already in the process of being made into a film and that producers were looking for a director.[7] Higuchinsky described the lure of Uzumaki using the Japanese word kikai, which translates to "strange and mysterious things (or people)", and that "the allure of Uzumaki is not that the uzumaki itself is scary but rather the changes in the people caught up in it. "[7] The original production of the film was going to be an independent production and would be part of an anthology film, but during production, Toei Animation decided to have it become a bigger film.[7] The film was backed by Toyoyuki Yokohama's Omega Project, a company that married Japanese and foreign funding to make J-horror films for an international market.[8] The company had previously had success with the 1999 film Audition.[4]

Production

[edit]Higuchinsky desired to be faithful to the manga as possible.[7] At the time, the manga had not been completed yet.[7] To help his crew express a Japanese style in the film, he had his staff watch Akuma no temari uta.[9] The film was primarily shot in Ueda, Nagano Prefecture, with a few locations in Tokyo.[7] Higuchinsky said the film was shot in about two weeks.[7]

Promotion and release

[edit]Uzumaki was released in Japan on 11 February 2000.[1] It was released as the first half of a double bill with Tomie: Replay,[1][6] a film based on the manga Tomie, also by Ito. The film was released concurrently in the United States as it was in Japan with a limited run in San Francisco.[8] Omega's vice-president Akiko Funatsu stated that San Francisco was chosen due to "all the internet activity there".[8] Based on grosses from Japan's nine key cities, the films opened in 14th place for the week.[10]

The film was shown at the 2000 Fantasia Film Festival.[11]

Reception

[edit]On review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an approval rating of 61% based on 28 reviews, with an average rating of 6.30/10. The site's critics consensus reads, "Uzumaki uses its creepy, David Lynch-inspired atmospherics to effectively build a sense of dread, but ultimately fails to do anything with it."[12] On Metacritic, the film has a score of 62 out of 100 based on nine critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[13]

In his review of the film for The New York Times, critic Elvis Mitchell noted the way the film develops mood, finding it part of the cycle of Japanese films like Kiyoshi Kurosawa's Cure and Hideo Nakata's Ring as "vivid, state-of-the-art scare films that move so swiftly that psychological underpinnings are a luxury".[3] Mitchell concluded that in the film that "things really get weird, though not particularly scary", calling the film "ultimately disappointing".[3] Variety's Dennis Harvey described the film as "intriguing, if ultimately unsatisfying", and criticized a perceived lack of atmosphere between set pieces, along with its "typically bland, schoolgirlish heroine."[2] Kim Morgan of The Oregonian described the film as "beautiful, cold, oddly colorful and just plain otherworldly"; she wrote that it contains "many creatively terrifying and effectively gross sequences that stand on their own beautifully", but lamented that it "doesn't flow into a consistent building of terror".[14]

Ross Williams of Film Threat praised the film's sound design and "cheesy, yet at the same time impressive and effective" special effects, writing: "While not as effectively creepy as The Ring, [Uzumaki] undoubtedly deserves to be watched".[15] Scott Tobias of The A.V. Club noted the style of the film, opining that kinetic shooting style doesn't pause for anything; like a lot of music-video and commercial directors, his achievement is better considered shot-by-shot than as a whole."[16] AllMovie's Josh Ralske gave the film a score of three-and-a-half stars out of five, calling it "visually imaginative and engagingly offbeat horror film, but its willful goofiness and unresolved story line doesn't offer much in the way of psychological resonance."[17]

Higuchinsky stated that, since the film's release, he has received fan mail from Europe, which made him particularly happy as it was his "dream to use film as a way to overcome national borders and have my movies watched by people all over the world. I think that these fans focus not on the story but on the simple images, they sense something through the visuals."[9]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Kalat 2007, p. 280.

- ^ a b c d e f Harvey, Dennis (24 April 2000). "Review: 'Whirlpool'". Variety. Archived from the original on 30 January 2022. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- ^ a b c Mitchell, Elvis (1 May 2002). "Uzumaki (2000) Film Review; A Town Reels When Son of Slinky Takes Revenge". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 April 2014. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- ^ a b c d Kalat 2007, p. 90.

- ^ Kalat 2007, p. 86.

- ^ a b c Kalat 2007, p. 87.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Edwards 2017, p. 177.

- ^ a b c Kalat 2007, p. 91.

- ^ a b Edwards 2017, p. 179.

- ^ "International box office: Japan". Screen International. 25 February 2000. p. 39.

- ^ "Movie Listings 2000". Fantasia Film Festival. Archived from the original on 6 October 2001. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- ^ "Uzumaki (2002)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Archived from the original on 7 December 2021. Retrieved 13 November 2019.

- ^ "Spiral (2002) Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- ^ Morgan, Kim (May 31, 2002). "'Uzumaki' a spiral of scary freakiness". The Oregonian. Archived from the original on July 11, 2002. Retrieved February 19, 2016.

- ^ Williams, Ross. "Uzumaki". Film Threat. Archived from the original on 12 August 2002. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- ^ Tobias, Scott (7 October 2002). "Uzumaki". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on 1 March 2016. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- ^ Ralske, Josh. "Uzumaki (2000)". AllMovie. Archived from the original on 2 March 2016. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

Bibliography

[edit]- Kalat, David (2007). J-horror: The Definitive Guide to The Ring, The Grudge and Beyond. Vertical. ISBN 978-1932234084.

- Edwards, Matthew (2017). Twisted Visions: Interviews with Cult Horror Filmmakers. McFarland. ISBN 978-1476663760.

External links

[edit]- Uzumaki at IMDb

- Uzumaki at Anime News Network's encyclopedia

- "- Uzumaki - A Higuchinsky Film -". Archived from the original on 21 February 2003. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)