Ulay

Ulay | |

|---|---|

Ulay in 1972 | |

| Born | Frank Uwe Laysiepen 30 November 1943 |

| Died | 2 March 2020 (aged 76)[1] |

| Nationality | German |

| Known for | Performance art |

| Notable work | Works with Marina Abramović (1976–1988) |

Frank Uwe Laysiepen (German: [fʁaŋk ˈʔuːvə laɪˈziːpm̩]; 30 November 1943 – 2 March 2020), known professionally as Ulay, was a German artist based in Amsterdam and Ljubljana, who received international recognition for his Polaroid art and collaborative performance art with longtime companion Marina Abramović.

Early career

[edit]In the early 1970s, struggling with his sense of "Germanness",[2] Ulay moved to Amsterdam, where he began experimenting with the medium of Polaroid. Renais sense (1974), a series of self-reflective and autobiographical collages, depicted overt visual representations of a constructed gender[3] that were considered scandalous at the time.[4]

Works with Marina Abramović

[edit]

In 1975, Laysiepen, who went by the mononym Ulay, met the Serbian performance artist Marina Abramović. They began living and performing together that year. When Abramović and Ulay began their collaboration,[5] the main concepts they explored were the Ego and artistic identity. They created "relation works" characterized by constant movement, change, process and "art vital".[6] The couple expressed their commitment in their Relation Works (1976–1988) manifesto: ‘Art Vital: No fixed living place, permanent movement, direct contact, local relation, self-selection, passing limitations, taking risks, mobile energy.’

This was the beginning of a decade of influential collaborative work. Each performer was interested in the traditions of their cultural heritage and the individual's desire for ritual. Consequently, they decided to form a collective being called "The Other", and spoke of themselves as parts of a "two-headed body".[7] They dressed and behaved like twins and created a relationship of complete trust. As they defined this phantom identity, their individual identities became less accessible. In an analysis of phantom artistic identities, Charles Green has noted that this allowed a deeper understanding of the artist as performer, for it revealed a way of "having the artistic self-made available for self-scrutiny".[8]

The work of Abramović and Ulay tested the physical limits of the body and explored male and female principles, psychic energy, transcendental meditation and nonverbal communication.[6] While some critics have explored the idea of a hermaphroditic state of being as a feminist statement, Abramović herself denies considering this as a conscious concept. Her body studies, she insists, have always been concerned primarily with the body as the unit of an individual, a tendency she traces to her parents' military pasts. Rather than concerning themselves with gender ideologies, Abramović/Ulay explored extreme states of consciousness and their relationship to architectural space. They devised a series of works in which their bodies created additional spaces for audience interaction. In discussing this phase of her performance history, she has said: "The main problem in this relationship was what to do with the two artists' egos. I had to find out how to put my ego down, as did he, to create something like a hermaphroditic state of being that we called the death self."[9]

- In Relation in Space (1976) they ran into each other repeatedly for an hour – mixing male and female energy into the third component called "that self".[5]

- Relation in Movement (1977) had the pair driving their car inside of a museum for 365 laps; a black liquid oozed from the car, forming a kind of sculpture, each lap representing a day. (After 365 laps the idea was that they entered the New Millennium.)

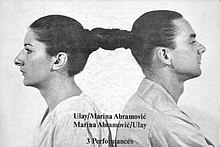

- In Relation in Time (1977) they sat back to back, tied together by their ponytails for sixteen hours. They then allowed the public to enter the room to see if they could use the energy of the public to push their limits even further.[10]

- To create Breathing In/Breathing Out the two artists devised a piece in which they connected their mouths and took in each other's exhaled breaths until they had used up all of the available oxygen. Seventeen minutes after the beginning of the performance they both fell to the floor unconscious, their lungs having filled with carbon dioxide.[11][12]

- In Imponderabilia (1977, reenacted in 2010) two performers, both completely nude, stand in a doorway. The public must squeeze between them in order to pass, and in doing so choose which one of them to face.[5]

- In AAA-AAA (1978) the two artists stood opposite each other and made long sounds with their mouths open. They gradually moved closer and closer, until they were eventually yelling directly into each other's mouths.[10] This piece demonstrated their interest in endurance and duration.[10]

- In 1980, they performed Rest Energy, in an art exhibition in Dublin, where both balanced each other on opposite sides of a drawn bow and arrow, with the arrow pointed at Abramović's heart. With almost no effort, Ulay could easily kill Abramović with one finger. This seems to symbolize the dominance of men and what kind of upper hand they have in society over women. In addition, the handle of the bow is held by Abramović and is pointed at herself. The handle of the bow is the most significant part of a bow. This would be a whole different piece if it were a Ulay aiming a bow at an Abramović, but by having her hold the bow, it is almost as if the she is supporting him while taking her own life.[5][13]

Between 1981 and 1987, the pair performed Nightsea Crossing in twenty-two performances. They sat silently across from each other in chairs for seven hours a day.[10]

In 1988, after several years of tense relations, Abramović and Ulay decided to make a spiritual journey which would end their relationship. They each walked the Great Wall of China, in a piece called Lovers, starting from the two opposite ends and meeting in the middle.[14] As Abramović described it: "That walk became a complete personal drama. Ulay started from the Gobi Desert and I from the Yellow Sea. After each of us walked 2500 km, we met in the middle and said good-bye."[15] She has said that she conceived this walk in a dream, and it provided what she thought was an appropriate, romantic ending to a relationship full of mysticism, energy, and attraction. She later described the process: "We needed a certain form of ending, after this huge distance walking towards each other. It is very human. It is in a way more dramatic, more like a film ending ... Because in the end, you are really alone, whatever you do."[15] She reported that during her walk she was reinterpreting her connection to the physical world and to nature. She felt that the metals in the ground influenced her mood and state of being; she also pondered the Chinese myths in which the Great Wall has been described as a "dragon of energy." It took the couple eight years to acquire permission from the government of the People's Republic of China to perform the work, by the time of which their relationship had completely dissolved.

At her 2010 MoMA retrospective, Abramović performed The Artist Is Present, in which she shared a period of silence with each stranger who sat in front of her. Although "they met and talked the morning of the opening",[16] Abramović had a deeply emotional reaction to Ulay when he arrived at her performance, reaching out to him across the table between them; the video of the event went viral.[17]

In November 2015, Ulay took Abramović to court, claiming she had paid him insufficient royalties according to the terms of a 1999 contract covering sales of their joint works.[18][19] In September 2016, a Dutch court ordered Abramović to pay €250,000 to Ulay as his share of sales of artistic collaborations over their joint works. In its ruling, the court in Amsterdam found that Ulay was entitled to royalties of 20% net on the sales of their works, as specified in the original 1999 contract, and ordered Abramović to backdate royalties of more than €250,000, as well as more than €23,000 in legal costs.[20] Additionally, she was ordered to provide full accreditation to joint works listed as by "Ulay/Abramović" covering the period from 1976 to 1980, and "Abramović/Ulay" for those from 1981 to 1988.

Later works

[edit]Ulay experimented extensively with incorporating audience participation into his performance art. His installations Can’t Beat the Feeling: Long Playing Record (1991–1992) and Bread and Butter (1993) were openly critical of European Union expansion.[21] In the Berlin Afterimages – EU Flags series, he exploited the phenomenon of retinal afterimages to depict reversed images of EU member nation flags.[5][22] He produced The Delusion: An Event about Art and Psychiatry (2002) on the grounds of the Vincent van Gogh Psychiatric Institute in Venray, the Netherlands. Other projects that incorporated audience participation include Luxembourg Portraits and A Monument for the Future.[23][24]

Rendering reality as accurately as possible was the focus of Cursive and Radicals (2000), Johnny–The Ontological in the Photographic Image (2004),[25] and WE Emerge (2004), the last realized in collaboration with AoRTa art centre in Chișinău, Republic of Moldova.[26]

Personal life

[edit]From 1976 to 1988 Ulay was in a relationship with Marina Abramović, with whom he collaborated on a number of pieces of performance art.

In 2013, director Damjan Kozole released the documentary Project Cancer: Ulay's journal from November to November about the artist's life, work and 2011 cancer diagnosis. The film follows Ulay's treatments, meetings with friends and travels, as well as his ongoing practice. He recovered from the lymphatic cancer in 2014.[27]

He died on 2 March 2020 in Ljubljana, Slovenia, aged 76, after the lymphatic cancer recurred.[1][28]

Prizes and awards

[edit]- 1984: The San Sebastian Video Award

- 1985: The Lucano Video Award

- 1986: The Polaroid Video Award

- 1986: Video Award – Kulturkreis im Verband der Deutschen Industrie

Bibliography

[edit]- Modus Vivendi. Ulay and Marina Abramović 1980 -1985, ed. Jan Debbaut; Stedelijk Van Abbemuseum Eindhoven, 1985

- Ulay: Life-Sized, ed. Matthias Ulrich. Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt. Spector Books, Leipzig, 2016; 978-3-95905-111-8; 3-95905-111-5

- Ulay, Portraits 1970 - 1993, ed. Frido Troost; Basalt Publishers, Amsterdam, 1996; ISBN 978-90-75574-05-0

- Ulay. Luxemburger Porträts, authors: Marita Ruiter, Lucien Kayser; Editions Clairefointaine, 1997; ISBN 2-919881-02-7

- Ulay/Abramović. Performances 1976 -1988, authors: Ulay, Marina Abramović, Chrissie Iles, Paul Kokke; Stedelijk Van Abbemuseum Eindhoven, 1997; ISBN 90-70149-60-5

- Ulay - Berlin/Photogene, ed. Ikuo Saito; The Yamaguchi Prefectural Museum of Art, Kameyama, 1997

- Ulay / What is That Thing Called Photography, artist's book; Artists' Books Johan Deumens, Landgraaf, 2000; ISBN 90-73974-05-4

- Ulay. WE EMERGE, authors: Thomas McEvilley, Irina Grabovan; Art Centre AoRTa, 2004; ISBN 9975-9804-1-4

- ULAY. Nastati / Become, authors: Thomas McEvilley, Tevz Logar, Marina Abramović; Galerija Skuc, Ljubljana, 2010; ISBN 978-961-6751-27-8

- Art, Love, Friendship: Marina Abramović and Ulay, Together & Apart; author: Thomas McEvilley; McPherson & Company, 2010; ISBN 978-0-929701-93-6

- Marina Abramović. The Artist is Present, authors: Klaus Biesenbach, Jovana Stokić, Arthur C. Danto, Nancy Spector, Chrissie Iles; The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2010; ISBN 978-0-87070-747-6

- Glam! The Performance of Style, Tate Publishing, London, 2013; ISBN 978-1-849760-92-8

- Whispers: Ulay on Ulay, authors: Maria Rus Bojan, Alessandro Cassin; Valiz, Amsterdam, 2014; ISBN 978-90-78088-72-1

References

[edit]- ^ a b Marshall, Alex (2020-03-02). "Ulay, Boundary-Pushing Performance Artist, Dies at 76". The New York Times.

- ^ Cassin, A. in conversation with Ulay. Finding Identity: Unlearning. In Whispers: Ulay on Ulay, authors: Maria Rus Bojan, Alessandro Cassin; Valiz, Amsterdam, 2014 (pp. 189-192); ISBN 978-90-78088-72-1

- ^ Марина Абрамович и Улай помирились 30 лет спустя

- ^ Bojan, M. R. Body: Threshold of Knowledge, Signifying Surface and Generator of Artistic Expression. In Whispers: Ulay on Ulay, authors: Maria Rus Bojan, Alessandro Cassin; Valiz, Amsterdam, 2014 (p. 25); ISBN 978-90-78088-72-1

- ^ a b c d e "Marina Abramović". Archived from the original on February 21, 2015. Retrieved 2015-02-06.

- ^ a b Stiles, Kristine (2012). Theories and Documents of Contemporary Art, 2nd ed. University of California Press. pp. 808–809.

- ^ Quoted in Green, 37

- ^ Green, 41

- ^ Kaplan, 14

- ^ a b c d "Ulay/Abramović – Marina Abramović". Blogs.uoregon.edu. February 12, 2015. Retrieved 2017-03-10.

- ^ Concerning Consequences: Studies in Art, Destruction, and Trauma

- ^ Marina Abramovic

- ^ "Documenting the performance art of Marina Abramović in pictures | Art | Agenda". Phaidon. Archived from the original on 2015-02-06. Retrieved 2017-03-10.

- ^ Cascone, Sarah (2017-08-08). "Marina Abramović and Ulay, Whose Breakup Changed Performance Art Forever, Make Peace in a New Interview". Artnet News.

- ^ a b "Lovers Abramović & Ulay Walk the Length of the Great Wall of China from opposite ends, Meet in the Middle and BreakUp – Kickass Trips". January 14, 2015. Retrieved 2016-09-29.

- ^ "Klaus Biesenbach on the AbramovicUlay Reunion | Artinfo". www.blouinartinfo.com. Archived from the original on 2013-04-20.

- ^ "Video of Marina Abramović and Ulay at MoMA retrospective". Youtube.com. December 15, 2012. Archived from the original on 2021-12-13. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ^ Esther Addley and Noah Charney. "Marina Abramović sued by former lover and collaborator Ulay | Art and design". The Guardian. Retrieved 2017-03-10.

- ^ Noah Charney. "Ulay v Marina: how art's power couple went to war | Art and design". The Guardian. Retrieved 2017-03-10.

- ^ Noah Ben Quinn. "Marina Abramović ex-partner Ulay claims victory in case of joint work | Art and design". The Guardian. Retrieved 2017-03-29.

- ^ Ulay zu Gast am ZKM

- ^ Interview von Carola Padtberg

- ^ Zum Tod des Künstlers Ulay - Der Alltagsweise

- ^ Was wichtig wird – Marina Abramovic und Ulay versöhnen sich

- ^ Bojan, M. R. Performing Communities: Participatory Aesthetics. In Whispers: Ulay on Ulay, authors: Maria Rus Bojan, Alessandro Cassin; Valiz, Amsterdam, 2014 (p. 43); ISBN 978-90-78088-72-1

- ^ Выживут только художники: 3 главных перформанса Марины Абрамович и Улая

- ^ Sayej, Nadja (2016-05-06). "Marina Abramović's former partner Ulay returns to the stage". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2019-11-16.

- ^ Needham, Alex (2020-03-02). "'A pioneer and provocateur': Performance artist Ulay dies aged 76". The Guardian.