Willow Rosenberg

| Willow Rosenberg | |

|---|---|

| Buffy the Vampire Slayer / Angel character | |

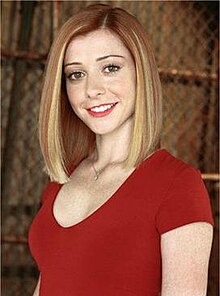

Alyson Hannigan as Willow Rosenberg in 2001 | |

| First appearance | "Welcome to the Hellmouth" (1997) |

| Last appearance | Finale (2018) |

| Created by | Joss Whedon |

| Portrayed by | Alyson Hannigan |

| In-universe information | |

| Full name | Willow Danielle Rosenberg |

| Affiliation | Scooby Gang Angel Investigations (ally) |

| Incredible powers | Powerful magical abilities |

Willow Rosenberg is a fictional character created for the fantasy television series Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997–2003). She was developed by Joss Whedon and portrayed throughout the TV series by Alyson Hannigan.

Willow plays an integral role within the inner circle of friends—called the Scooby Gang—who support Buffy Summers (Sarah Michelle Gellar), a teenager gifted with superhuman powers to defeat vampires, demons, and other evil in the fictional town of Sunnydale. The series begins as Buffy, Willow, and their friend Xander (Nicholas Brendon) are in 10th grade and Willow is a shy, nerdy girl with little confidence. She has inherent magical abilities and begins to study witchcraft; as the series progresses, Willow becomes more sure of herself and her magical powers become significant. Her dependence on magic becomes so consuming that it develops into a dark force that takes her on a redemptive journey in a major story arc when she becomes the sixth season's main villain, threatening to destroy the world in a fit of grief and rage.

The Buffy series became extremely popular and earned a devoted fanbase; Willow's intelligence, shy nature, and vulnerability often resounded strongly with viewers in early seasons. Of the core characters, Willow changes the most, becoming a complex portrayal of a woman whose powers force her to seek balance between what is best for the people she loves and what she is capable of doing. Her character stood out as a positive portrayal of a Jewish woman and at the height of her popularity, she fell in love with another woman, a witch named Tara Maclay (Amber Benson). They became one of the first lesbian couples on U.S. television and one of the most positive relationships of the series.

Despite not being a titular character, Willow Rosenberg holds the distinction of having the second largest number of appearances on episodes of Buffy and the spin-off series Angel. Alyson Hannigan appeared as Willow in all 144 episodes of Buffy, as well as guest appearances in three episodes of the spinoff Angel, for a total of 147 on-screen appearances over the course of both series. She is also featured in an animated series and video game, both of which use Hannigan's voice, and the comics Buffy the Vampire Slayer Season Eight (2007–2011), Buffy the Vampire Slayer Season Nine (2011-2013), Buffy the Vampire Slayer Season Ten (2014-2016), Buffy the Vampire Slayer Season Eleven (2016-2017) and Buffy the Vampire Slayer Season Twelve (2018) which use Hannigan's likeness and continues Willow's storyline following the television series.

Character history

[edit]Pilot and casting

[edit]Buffy the Vampire Slayer (often simplified as Buffy) was originally conceived by Joss Whedon for a 1992 feature film. However, in its development Whedon felt it lost some of the quirkiness he considered was the heart of the project, and it was not received as well as he would have liked. He began to develop for television the concept of a fashion-conscious girl named Buffy, who is imbued with superhuman abilities and attends a high school situated on a portal to hell.[1] Whedon created a group of friends for the main character, including Willow Rosenberg and Xander Harris. A half-hour pilot was filmed starring Riff Regan as Willow, but it was eventually left unaired and network executives requested that Regan be replaced. Willow's character demanded that she be shy and unsure of herself, and the casting department encountered some difficulty finding actors who could portray this effectively and still be likable.[2] Melanie Lynskey turned down the role as she wasn't interested in TV acting at the time.[3] After seven auditions, 23-year-old Alyson Hannigan was hired for the role.[4] She was chosen for being able to spin the character's lines with a self-effacing optimism. She later stated in an interview, "I didn't want to do Willow as someone who's feeling sorry for herself. Especially in the first season, she couldn't talk to guys, and nobody liked her. I was like, 'I don't want to play somebody who's down on herself.'"[5]

In the beginning of the series, Hannigan used her own experiences in high school—which she called "overwhelmingly depressing"[5]—to guide her portrayal of Willow: "My theory on high school was, get in, get out and hopefully I won't get hurt. Basically it was a miserable experience, because you're a walking hormone in this place that is just so cruel. There were times that were OK, but it's not the little myth that high school is the best years of your life. No way."[6][7] Whedon intended Willow to be realistically introverted, saying, "I wanted Willow to have that kind of insanely colorful interior life that truly shy people have. And Alyson has that. She definitely has a loopiness I found creeping into the way Willow talked, which was great. To an extent, all the actors conform to the way I write the character, but it really stands out in Willow's case."[8]

Television series (1997–2003)

[edit]Seasons 1–3

[edit]The Buffy television series first aired mid-season in March 1997, almost immediately earning positive critical reviews.[9][10] Willow is presented as a bookish nerd with considerable computer skills, dowdily dressed and easily intimidated by more popular girls in school. She grows faint at the sight of monsters, but quickly forms a friendship with Buffy and is revealed to have grown up with Xander (Nicholas Brendon). They are mentored by the school librarian who is also Buffy's Watcher, Rupert Giles (Anthony Stewart Head), who often works closely with Willow in researching the various monsters the group encounters. Joss Whedon found that Hannigan was especially gifted reacting with fear (calling her the "king of pain") and viewers responded strongly when she was placed in danger, needing to be rescued by Buffy. Scenarios with Willow in various predicaments became common in early episodes.[11][12] However, Willow establishes herself as integral to the group's effectiveness, often willing to break rules by hacking into highly secure computer systems.[13]

In the second season when the characters are in 11th grade, Willow becomes more sure of herself, standing up to the conceited Cordelia Chase (Charisma Carpenter), and approaching Xander, on whom she has had a crush for years, although it is unrequited as Xander is in love with Buffy. Seth Green joined the cast during the second season as Oz, a high school senior who becomes a werewolf, and Willow's primary romantic interest. The show's popularity by early 1998 was evident to the cast members, and Hannigan remarked on her surprise specifically.[4] Willow was noted to be the spirit of the Scooby Gang, and Hannigan attributed Willow's popularity with viewers (she had by May 1998 seven websites devoted to her) to being an underdog who develops confidence and is accepted by Buffy, a strong, popular person in school.[7] Hannigan described her appeal: "Willow is the only reality-based character. She really is what a lot of high-schoolers are like, with that awkwardness and shyness, and all those adolescent feelings."[14]

At the end of the second season, Willow begins to study magic following the murder of the computer teacher and spell caster Jenny Calendar (Robia LaMorte). Willow is able to perform a complicated spell to restore the soul of Angel (David Boreanaz), a vampire who is also Calendar's murderer and Buffy's boyfriend. During the third season three episodes explore Willow's backstory and foreshadow her development. In "Gingerbread", her home life is made clearer: Sunnydale falls under the spell of a demon who throws the town's adults into a moral panic, and Willow's mother Sheila (Jordan Baker) is portrayed as a career-obsessed academic who is unable to communicate with her daughter, eventually trying to burn Willow at the stake for being involved in witchcraft;[15] her father is never featured. In "The Wish" a vengeance demon named Anya (Emma Caulfield) grants Cordelia's wish that Buffy never came to Sunnydale, showing what would happen if it were overrun with vampires. In this alternate reality, Willow is an aggressively bisexual vampire. In a related episode, "Doppelgangland", Willow meets "Vamp Willow", who dresses provocatively and flirts with her.[16]

Seasons 4–6

[edit]Willow chooses to attend college with Buffy in Sunnydale although she is accepted to prestigious schools elsewhere. Her relationships with Buffy and Xander become strained as they try to find their place following high school. Willow becomes much more confident in college, finally finding a place that respects her intellect, while Buffy has difficulty in classes and Xander does not attend school. Willow's relationship with her boyfriend, Oz, continues until a female werewolf appears on the scene, aggressively pursuing him, and he leaves town to learn how to control the wolf within. She becomes depressed and explores magic more deeply, often with powerful but inconsistent results. She joins the campus Wicca group, meeting Tara Maclay, for whom she immediately feels a strong attraction. Willow adapts to her newfound sexual identity, eventually falling in love with and choosing to be with Tara, even when Oz returns to Sunnydale after apparently getting his lycanthropic tendencies under control.[17]

Each season the Scoobies face a villain they call the Big Bad. In the fifth season, this is a goddess named Glory (Clare Kramer) that Buffy is unable to fight by herself.

The writers of the series often use elements of fantasy and horror as metaphors for real-life conflicts. The series' use of magic, as noted by religion professor Gregory Stevenson, neither promotes nor denigrates Wiccan ideals and Willow rejects Wiccan colleagues for not practicing the magic she favors. Throughout the series, magic is employed to represent different ideas -— relationships, sexuality, ostracism, power, and particularly for Willow, addiction -— that change between episodes and seasons. The ethical judgment of magic, therefore, lies in the results: performing magic to meet selfish needs or neglecting to appreciate its power often ends disastrously. Using it wisely for altruistic reasons is considered a positive act on the series.[18]

Through witchcraft, Willow becomes the only member of the group to cause damage to Glory. She reveals that the spells she casts are physically demanding, giving her headaches and nosebleeds. When Glory assaults Tara, making her insane, Willow, in a magical rage that causes her eyes to turn black, finds Glory and battles her. She does not come from the battle unscathed (after all, Glory is a goddess and Willow "just" a very powerful witch) and must be assisted by Buffy, but her power is evident and surprising to her friends. The final episode of the fifth season sees Willow restoring Tara's sanity and crucially weakening Glory in the process. It also features Buffy's death, sacrificing herself to save the world.[19]

Willow and Tara move into the Summers house and raise Buffy's younger sister Dawn (Michelle Trachtenberg). Fearing that Buffy is in hell, Willow suggests at the beginning of the sixth season that she be raised from the dead. In a dark ceremony in which she expels a snake from her mouth, Willow performs the magic necessary to bring Buffy back. She is successful, but Buffy keeps it secret that she believes she was in heaven.

Willow's powers grow stronger; she uses telepathy which her friends find intrusive, and she begins to cast spells to manipulate Tara. After Willow fails Tara's challenge to go for one week without performing magic, Tara leaves her, and for two episodes Willow descends into addiction that almost gets Dawn killed. Willow goes for months without any magic, helping Buffy track three geeks called The Trio who grandiosely aspire to be supervillains.

Immediately following Willow's reconciliation with Tara, Warren (Adam Busch), one of the Trio, shoots Buffy; a stray shot kills Tara right in front of Willow. In an explosion of rage and grief, Willow soaks up all the dark magic she can, which turns her hair and eyes black. In the final episodes of the season Willow becomes exceedingly strong, surviving unharmed when Warren hits her in the back with an axe. “Axe not gonna cut it,” she quips. She hunts Warren, tortures him by slowly pushing a bullet into his body, then kills him by magically flaying him. Unsatisfied, she attempts to kill the other two members of the Trio but is unsuccessful due to her weakening power. She solves this problem by killing her 'dealer' from earlier in the season and draining him of his magic. When she is confronted by Buffy they begin to fight, only to be stopped by Giles who has borrowed magic from a coven of wiccans. Willow successfully drains him of this borrowed magic, fulfilling his plan and causing her to feel all the pain of everyone in the world. She tries to ease the pain by destroying the world, finally stopped by Xander’s passionate confession of platonic familial love for her.[20]

Season 7

[edit]The seventh season starts with Willow in England, unnerved by her power, studying with a coven near Giles' home to harness it. She fears returning to Sunnydale and what she is capable of doing if she loses control again, a fear that dogs her the whole season.

Buffy and the Scoobies face the First Evil, bent on ending the Slayer line and destroying the world. Potential Slayers from around the globe congregate at Buffy's home and she trains them to battle the First Evil. Willow continues to face her grief over Tara's death and, reluctantly, becomes involved with one of the Potentials, Kennedy (Iyari Limon).

In the final episode of the series, "Chosen", Buffy calls upon Willow to perform the most powerful spell she has ever attempted. With Kennedy nearby, cautioned to kill her if she becomes out of control, Willow infuses every Potential Slayer in the world with the same powers Buffy and Faith have. The spell momentarily turns her hair white and makes her glow—Kennedy calls her "a goddess"—and it ensures that Buffy and the Potentials defeat the First Evil. Willow is able to escape with Buffy, Xander, Giles, Faith and Kennedy as Sunnydale is destroyed.[21]

Through the gamut of changes Willow endures in the series, Buffy studies scholar Ian Shuttleworth states that Alyson Hannigan's performances are the reason for Willow's popularity: "Hannigan can play on audience heartstrings like a concert harpist... As an actress she is a perfect interpreter in particular of the bare emotional directness which is the specialty of [series writer Marti] Noxon on form."[22]

Comic series (since 2007)

[edit]

Subsequent to Buffy's television finale, Dark Horse Comics collaborated with Joss Whedon to produce a canonical comic book continuation of the series, Buffy the Vampire Slayer Season Eight (2007–11), written by Whedon and many other writers from the television series. Unfettered by the practical limitations of casting or a television special effects budget, Season Eight explores more fantastic storylines, characters, and abilities for Willow. Willow's cover art is done by Jo Chen, and Georges Jeanty and Karl Moline produce character artwork and provide alternative covers. It was followed by two closely interlinked sequels, Buffy the Vampire Slayer Season Nine and Angel & Faith (both 2012–14).[23][24] Willow features at different times in both series, as well as in her own spin-off miniseries.[25] Jeanty continues to provide Willow's likeness in Season Nine, while Rebekah Isaacs and Brian Ching are the primary pencillers of Angel & Faith and Willow: Wonderland respectively. While Season Nine and Angel & Faith are substantially less fantastical in tone than Season Eight,[24] Willow's spin-off is high fantasy and focuses on her journey through magical alternate worlds.[25]

Willow appears to Buffy and Xander, who are in charge of thousands of Slayers, a year after the destruction of Sunnydale. Willow reveals a host of new abilities including being able to fly and absorbing others' magic to deconstruct it. The Big Bad of Season Eight is a being named Twilight who is bent on destroying magic in the world.[26] A one-shot comic dedicated to Willow's story was released in 2009 titled Willow: Goddesses and Monsters. It explores the time she took away to discover more about her magical powers, under the tutelage of a half-woman half-snake demon named Aluwyn. Willow is still involved with Kennedy through Season Eight, but becomes intimate with Aluwyn while they are together. She also continues to deal with grief from Tara's death, and struggles with the dark forces of magic that put her in opposition to Buffy.[27] At the conclusion of the season, Buffy destroys an object, a seed, that is the source of the magic in the world, leaving Willow powerless.[28] Whedon divulged that recovering her magical abilities will become Willow's "personal obsession" in a miniseries where she will be the central character.[24]

Other Publications

[edit]Willow returns to Sunnydale in Kendare Blake’s young adult novels, Buffy: The Next Generation Series. This trilogy is a sequel series to the television show and focuses on Frankie Rosenberg, Willow’s daughter.

Identities

[edit]From the inception of Willow's character in the first season, she is presented with contradictions. Bookish, rational, naive, and sometimes absent-minded, she is also shown being open to magic, aggressively boyish, and intensely focused. Willow is malleable, in continuous transition more so than any other Buffy character. She is, however, consistently labeled as dependable and reliable by the other characters and thus to the audience, making her appear to be stable.[29] She is unsure of who she is; despite all the tasks she takes on and excels at, for much of the series she has no identity.[30] This is specifically exhibited in the fourth season finale "Restless", an enigmatic pastiche of characters' dream sequences. In Willow's dream, she moves from an intimate moment painting a love poem by Sappho on Tara's bare back,[note 1] to attending the first day of drama class to learn that she is to be in a play performed immediately for which she does not know the lines or understand. The dream presents poignant anxieties about how she appears to others, not belonging, and the consequences of people finding out her true self. As Willow gives a book report in front of her high school class, she discovers herself wearing the same mousy outfit she wore in the first episode of the show ("Welcome to the Hellmouth") as her friends and classmates shout derisively at her, and Oz and Tara whisper intimately to each other in the audience. She is attacked and strangled by the First Slayer as the class ignores her cries for help.[31][32]

Long a level-headed character who sacrifices her own desires for those of her friends, she gradually abandons these priorities to be more independent and please herself. She is often shown making choices that allow her to acquire power or knowledge and avoid emotional conflict.[33] The story arc of Willow's growing dependence on magic was noted by Marti Noxon as the representation of "adult crossroads" and Willow's inability and unwillingness to be accountable for her own life. Willow enjoys power she is unable to control. She steals to accomplish her vocational goals and rationalizes her amoral behavior. This also manifests itself in a competitive streak and she accuses others who share their concerns that she uses magic for selfish purposes of being jealous. No longer the conscience of the Scooby Gang, Willow cedes this role to Tara then revels in breaking more rules.[34] After Tara leaves Willow, Willow divulges to Buffy that she does not know who she is and doubts her worth and appeal—specifically to Tara—without magic. Contradicting the characterization of Willow's issues with magic as addiction, Buffy essayist Jacqueline Lichtenberg writes "Willow is not addicted to magic. Willow is addicted to the surging hope that this deed or the next or the next will finally assuage her inner pain."[35]

Vamp Willow

[edit]Vamp Willow appears in the third season episodes "The Wish" and "Doppelgangland". She is capricious and aggressive, the opposite of Willow's usual nature; her bad behavior so exaggerated that it does not instill fear into the viewer like other female vampires in the series, but indicates more about Willow's personality. Shocked upon seeing her alter ego in "Doppelgangland", Willow states "That's me as a vampire? I'm so evil and skanky. And I think I'm kinda gay!" Angel is stopped by Buffy in telling the Scoobies that the vampire self carries many of the same attributes as the human self, at which Willow says that is nothing like her. Many Buffy fans saw this as a funny Easter egg when Willow revealed herself to actually be lesbian in later seasons.[29] As surprised as Willow is with Vamp Willow, she feels bound to her, and does not have the heart to allow Buffy to kill her. Both Willows make the observation that "this world's no fun",[36] before they send Vamp Willow back into the alternate dimension from which she came, whereupon she is staked and dies immediately.[37]

Dark Willow

[edit]A shadow of Dark Willow appears to fight Glory in the fifth season episode "Tough Love", but she does not come into full force until the sixth season in "Villains", "Two to Go", and "Grave". The transition from Willow into Dark Willow, precipitated by Tara's immediate death when she is shot through the heart, was ambiguously received by audiences, many of whom never foresaw Willow's psychic break. It was simultaneously lauded for being an overwhelming depiction of a powerful woman, and derided as representative of a worn cliché that lesbians are amoral and murderous.[38][39] Dark Willow proved to be exceptionally more powerful than Buffy. She changes visually when she walks into the Magic Box, a store owned by Giles, telekinetically retrieves dozens of dark magic books from the shelves, and leeches the words from the pages with her fingertips. As the words crawl up her arms and soak into her skin, her eyes and hair become black and her posture "aggressively aware and confident".[40]

Susan Driver writes that it is "crucial to recognize that never before in a teen series has raw fury been so vividly explored through a young queer girl responding to the sudden death of her lover".[41] Dark Willow is preternaturally focused on revenge, relentless and unstoppable. Lights explode when she walks past. She forcefully takes advantage of any opportunity to further her goals. She saves Buffy by removing the bullet from her chest, but later commandeers a tractor trailer, making it slam into Xander's car while he and Buffy are inside protecting Jonathan and Andrew, the other two members of the Trio. She floats, flies[42] and dismantles the local jail where Jonathan and Andrew are held.

She is cruelly honest to Dawn and Buffy, and overpowers everyone with whom she comes in contact. When she takes Giles' magic from him, she gains the ability to feel the world's pain, becoming determined to put the world out of its misery. She does not acknowledge her grief, and only Xander can force her to face it when he tells her that he loves her no matter what or who she is, and if she is determined to end the world she must start by killing him. Only then does Willow return, sobbing.[43]

At Salon.com, Stephanie Zacharek writes that Dark Willow is "far from being a cut-out angry lesbian, is more fleshed out, and more terrifyingly alive, than she has ever been before. More than any other character, she has driven the momentum of the past few episodes; she very nearly drove it off a cliff."[44] Several writers state that Willow's transition into Dark Willow is inevitable, grounded in Willow's self-hatred that had been festering from the first season.[45][46] Both Dark Willow and even Willow herself state that Willow's sacrifices for her friends and lack of assertiveness are her undoing. In "Doppelgangland", Willow (posing as Vampire Willow) says "It's pathetic. She lets everyone walk all over her and gets cranky at her friends for no reason." In "Two to Go", Dark Willow remarks "Let me tell you something about Willow. She's a loser. And she always has been. People picked on Willow... and now Willow's a junkie." Vamp Willow served as an indicator of what Willow is capable of; immediately before she flays Warren in one violent magical flash, she uses the same line Vamp Willow used in the third season: "Bored now."[46][47]

Following the sixth season, Willow struggles to allow herself to perform magic without the darkness within her taking her over. She is no longer able to abstain from magic as it is such an integral part of her that doing so will kill her. In the instances when she is highly emotional the darkness comes out. Willow must control that part of her and is occasionally unable to do so, giving her a trait similar to Angel, a cursed vampire who fears losing his soul will turn him evil. In a redemptive turn, when Willow turns all the Potentials into Slayers, she glows and her hair turns white, astonishing Kennedy and prompting her to call Willow a goddess.[48]

Relationships

[edit]Willow's earliest and most consistent relationships are with Buffy and Xander, both of whom she refers to as her best friends although they have their conflicts, and Giles as a father figure. Willow takes on the leadership role when Buffy is unavailable, and her growing powers sometimes make her resent being positioned as Buffy's sidekick. Some scholars see Willow as Buffy's sister-figure or the anti-Buffy, similar to Faith, another Slayer whose morals are less strict.[49] In early seasons, Willow's unrequited crush on Xander creates some storylines involving the relationships between Xander, Cordelia, and Oz. Willow is part of a powerful quartet: she represents the spirit, Giles intelligence, Xander heart, and Buffy strength of the Scoobies. Although they often drift apart, they are forced to come together and work in these roles to defeat forces they are unable to fight individually.[50]

Oz

[edit]Willow meets stoic Oz in the second season. Their courtship is slow and patient. Oz is bitten by a werewolf, and just as Willow begins to confront him about why he does not spend time with her, he transforms and attacks her. She must shoot him with a tranquilizer gun several times while he is wild, but her assertiveness in doing so makes her more confident in their relationship.[51] Oz's trials in dealing with a power he cannot control is, according to authors J. Michael Richardson and J. Douglas Rabb, a model for Willow to reference when she encounters her own attraction to evil.[52] When Willow and Oz decide to commit to each other, Willow is enthusiastic that she has a boyfriend, and, as a guitarist in a band, one so cool.[53] Her relationship with Oz endures the high school storylines of exploring her attraction to Xander, which briefly separates them. She worries that she is not as close to Oz as she could be. They stay together through graduation into college, but Oz is drawn to Veruca, another werewolf. He admits an animal attraction to Veruca, which he does not share with Willow. He sleeps with Veruca and leaves shortly after to explore the werewolf part of himself. Willow becomes very depressed and doubts herself. She drinks, her magical abilities are compromised, her spells come out wrong, and she lashes out at her friends when they suggest she get over it ("Something Blue").[54][55]

Joss Whedon did not intend to write Oz out of the series. Seth Green came to Whedon early in the fourth season to announce that he wished to work on his film career. Whedon admitted he was upset by Green's announcement and that if he had wanted to continue, Oz would have been a part of the story. However, to resolve the relationship between Oz and Willow Whedon says, "we had to scramble. And out of the heavens came Amber Benson."[56]

Tara Maclay

[edit]

Buffy earned international attention for its unflinching focus on the relationship between Willow and Tara Maclay. Whedon and the writing staff had been considering developing a story arc in which a character explores his or her sexuality as the Scoobies left high school, but no particular effort was made to assign this arc to Willow. In 1999, at the end of the third season, the Boston Herald called Buffy "the most gay show on network TV this year" despite having no overtly gay characters among the core cast. It simply presented storylines that resembled coming out stories.[57] In the fourth season episode "Hush", Willow meets Tara, and to avoid being killed by a group of ghouls, they join hands to move a large vending machine telekinetically to barricade a door. The scene was, upon completion, noticeably sensual to Whedon, the producers, and network executives, who encouraged Whedon to develop a romantic storyline between Willow and Tara, but at the same time placed barriers on how far it could go and what could be shown.[58][59] Two episodes later, Hannigan and Amber Benson were informed that their characters would become romantically involved. The actors were not told the end result of the Willow–Oz–Tara storyline, not sure what the eventual trajectory of the relationship would be, until Hannigan said, "Then finally it was, 'Great! It's official. We're in luurrvvve.'"[60]

Whedon made a conscious effort to focus on Willow and Tara's relationship instead of either's identity as a lesbian or the coming out process. When Willow discloses to Buffy what she feels for Tara, she indicates that she has fallen in love with Tara, not that she is a lesbian, and avoids categorizing herself. Some critics regard this as a failure on Willow's part to be strong;[61] Em McAvan interprets this to mean that Willow may be bisexual.[62] Scholar Farah Mendlesohn asserts that Willow's realization that she is in love with Tara allows viewers to re-interpret Willow's relationship with Buffy; in the first three seasons, Willow is often disappointed that she is not a higher priority to Buffy, and even after Willow enters a relationship with Tara, still desires to feel integral to Buffy's cause and the Scooby Gang.[63]

Willow's progression has been noted to be unique in television. Her relationship with Tara coincides with the development of her magical abilities becoming much more profound. By the seventh season, she is the most powerful person in Buffy's circle. Jessica Ford at PopMatters asserts that Willow's sexuality and her magical abilities are connected and represented by her relationships. In her unrequited attraction to Xander, she has no power. With Oz, she has some that gives her the confidence she sorely lacks, but his departure leaves her unsure of herself. Only when she meets Tara do her magical abilities flourish; to Ford, sexuality and magic are both empowering agents in Willow's story arc.[64] David Bianculli in the New York Daily News writes that Willow's progression is "unlike anything else I can recall on regular prime-time television: a character evolving naturally over four seasons of stories and arriving at a place of sexual rediscovery".[65]

Not all viewers considered Willow and Tara's relationship a positive development. Some fans loyal to Willow reacted angrily as she chose to be with Tara when Oz made himself available, and they lashed out at Tara and Amber Benson on the fansite message boards. Whedon replied sardonically, "we're going to shift away from this whole lifestyle choice that Willow has made. Just wipe the slate. From now on, Willow will no longer be a Jew. And I think we can all breathe easier." However, he seriously explained his motivation, writing "My show is about emotion. Love is the most powerful, messy, delightful and dangerous emotion... Willow's in love. I think it's cool."[56] Hannigan was also positive about the way the character and her relationship with Tara was written: "It is not about being controversial or making a statement. I think the show is handling it really nicely. It's about two people who care about each other."[66]

Contrasting with some of the more sexual relationships of the other characters, Willow and Tara demonstrate a sentimental, soft, and consistent affection for each other. Some of this was pragmatic: the show was restricted in what it could present to viewers. Willow and Tara did not kiss until the fifth season in an episode that diverted the focus away from the display of affection when Buffy's mother dies in "The Body". Before this, much of their sexuality is represented by allusions to witchcraft; spells doubled for physical affection such as an erotic ritual in "Who Are You?" where Willow and Tara chant and perspire in a circle of light until Willow falls back on a pillow gasping and moaning.[note 2] Within the Buffy universe, magic is portrayed in a mostly female realm. As opposed to it being evil, it is an earth-bound force that is most proficiently harvested by women.[64] The treatment of the lesbian relationship as integral to magic, representative of each other (love is magic, magic is love), earned the series some critical commentary from conservative Christians.[52] To avoid large-scale criticism, scenes had to be shot several different ways because censors would not allow some types of action on screen. In the fourth and fifth seasons, the characters could be shown on a bed, but not under the covers. Hannigan noted the inconsistent standards with the other relationships on the show: "you've got Spike and Harmony just going at it like rabbits, so it's very hypocritical".[67] As a couple, Willow and Tara are treated by the rest of the Scoobies with acceptance and little fanfare. Susan Driver writes that younger viewers especially appreciate that Willow and Tara are able to be affectionate without becoming overly sexual, thus making them objects of fantasy for male enjoyment. Willow and Tara's influence on specifically younger female viewers is, according to Driver, "remarkable".[68]

Academics, however, comment that Willow is a less sexual character than the others in the show. She is displayed as "cuddly" in earlier seasons, often dressing in pink fuzzy sweaters resulting in an innocent tomboyishness. She becomes more feminine in her relationship with Tara, who is already feminine; no issues with gender are present in their union.[69][70] Their relationship is sanitized and unthreatening to male viewers. When the series moved broadcast networks from The WB to UPN in 2001, some of the restrictions were relaxed. Willow and Tara are shown in some scenes to be "intensely sexual", such as in the sixth season episode "Once More, with Feeling" where it is visually implied that Willow performs cunnilingus on Tara.[71] When Willow and Tara reconcile, they spend part of the episode in "Seeing Red" unclothed in bed, covered by red sheets.

Willow is more demonstrative in the beginning of her relationship with Tara. Where in her relationship with Oz she described herself as belonging to him, Tara states that she belongs to Willow. Willow finds in Tara a place where she can be the focus of Tara's attention, not having to appease or sacrifice as she has in the past. Tara, however, eclipses Willow's role as the moral center of the Scoobies, and as Willow becomes more powerful and less ethical, Tara becomes a maternal figure for the group.[72] Willow acts as a sort of middle child between Xander's immaturity and Buffy's weighty responsibilities. She becomes completely devoted to and enamored of Tara, and then manipulates her to avoid conflict when Tara does not conform to what she wants.[29] Displeased with how Willow abuses her power, especially toward herself, Tara leaves Willow while continuing to counsel Dawn and Buffy. Long after Tara's death, Willow faces the choices she made: in the Season Eight issue "Anywhere But Here", Willow tells Buffy that she is responsible for Tara's death. Her ambition to bring back Buffy from the dead inevitably led to Tara getting shot and killed. In the one-shot comic, Willow is offered Tara as a guide for her mystical path to understanding her own powers, but rejects her as being an illusion, too much of a comfort, and not a guide who will force her to grow. She begins a relationship with Kennedy.

Kennedy

[edit]Following protests angry about the death of Tara, Whedon and the writing team made a decision to keep Willow gay. In 2002, he told The Advocate about the possibility of Willow having a relationship with a man, "We do that now, and we will be burned alive. And possibly justifiably. We can't have Willow say, 'Oh, cured now, I can go back to cock!' Willow is not going to be straddling that particular fence. She will just be gay."[38] Kennedy is markedly different from Tara. She is younger, outspoken, and aggressively pursues Willow, who hesitates to become involved again.[73] When they first kiss in the episode "The Killer in Me", Willow's realization that she let Tara go reacts with a curse put upon her by another witch named Amy Madison (Elizabeth Anne Allen), turning Willow into Warren, Tara's murderer. The spell is broken when Willow acknowledges her guilt and Kennedy kisses her again. Kennedy expresses that she does not understand the value of magic and assumes it involves tricks, not the all-consuming energy that Willow is capable of. When Willow eventually exhibits what power she has, it briefly frightens Kennedy. Willow worries about becoming sexually intimate with Kennedy, unsure of what may transpire if she loses control of herself.[74] In season 7 episode 20, "Touched", in which practically all the main cast has sex (two by two) Willow and Kennedy take part in the first lesbian sex scene on primetime television.[75]

In Season Eight, Kennedy and Willow are still romantically involved, but separated during Willow's self-exploration. Unlike her relationship with Tara, Willow is able to hold a separate identity while with Kennedy.[76] When she realizes her powers have gone at the end of Season Eight, however, Willow ends her relationship with Kennedy, saying that there is someone else Willow is in love with, who she will never see again.[77] Kennedy's role split many Buffy fans into two groups. Many viewers hated Kennedy, because they saw her as a way of saying; "Tara's dead, let's move on." and they weren't ready to. After the emotional death of Tara and Willow's reaction (nearly ending all life on Earth) many fans thought that it was ridiculous for Willow to recover and move on so quickly. Kennedy overall, has received much hate, but there is the other side who say that she was exactly what Willow needed to recover and continue a happy life.

Cultural impact

[edit]Willow Rosenberg is undoubtedly the most complexly represented girl in love and lust with other girls to be developed within a mainstream network television series.

Susan Driver in Queer Girls and Popular Culture[78]

Willow's religion and sexuality have made her a role model for audiences. Whedon, however, has compared her Jewish identity to her sexuality, stating that they are rarely made a significant focus of the show.[79] Willow at times reminds the other characters of her religion, wondering what her father might think of the crucifixes she must apply to her bedroom wall to keep out vampires, and commenting that Santa Claus misses her house every Christmas because of the "big honkin' menorah". Buffy essayist Matthew Pateman criticizes the show for presenting Willow's Jewish identity only when it opposes Christian declarations of holidays and other traditions.[80] The New York Times, however, named her as a positive example of a depiction of a Jewish woman, who stood out among portrayals of Jews as harsh, unfeminine, and shallow. Producer Gail Berman states that as a Jew, Willow "handles herself just fine, thank you".[81]

In Queer Girls and Popular Culture, Susan Driver states that television ascribes to viewers what lesbians look and act like, and that realistic portrayals of girls outside the norm of white, upper or middle class, and heterosexual are extremely rare. Realistic depictions of lesbians are so rare that they become strong role models and enable "hope and imagination" for girls limited by the conditions of their immediate surroundings, who may know of no other gay people.[82] The time and space given to Willow to go from being a shy scared girl into a confident woman who falls in love with another woman is, as of 2007, unique in television; it does not occur in one flash or single moment. It is a progression that defies strict definition. Manda Scott in The Herald states that Willow's lack of panic or self-doubt when she realizes she is in love with Tara makes her "the best role model a teen could ask for".[83]

When viewers realized that Willow was falling in love with Tara, Whedon remembered that some threatened to boycott the show, complaining "You made Willow a fag", to which he responded, "Bye. We'll miss you a whole lot."[84] However, he also said, "For every (negative) post, there's somebody saying, 'You made my life a lot easier because I now have someone I can relate to on screen'."[59] Gay characters had been portrayed before on television, and at the time the popular sitcom Will & Grace was on the air. Lesbian-themed HBO special If These Walls Could Talk 2 won an Emmy. Twenty-three television shows depicted a gay character of some kind in 2000.[85] However, these other characters were mostly desexualized, none were partnered or shown consistently affectionate towards the same person. Willow and Tara's relationship became the first[citation needed] long-term lesbian relationship on U.S. television. Jane magazine hailed Willow and Tara as a bold representation of gay relationship, remarking that "they hold hands, slow-dance and lay in bed at night. You won't find that kind of normalcy on Will and Grace."[86] Despite Whedon's intentions of not making Buffy about overcoming issues, he said Willow's exploration of her sexuality "turned out to be one of the most important things we've done on the show".[84]

Although the show's writers and producers received a minimal negative reaction from Willow choosing Tara over Oz, the response from viewers and critics alike was overwhelming towards Whedon for killing Tara, accusing him of homophobia. Particularly because Tara's death came at a point where Willow and Tara had reconciled and were shown following an apparent sexual encounter, the writers were criticized for representing the consequences of lesbian sex as punishable by death. Series writer and producer Marti Noxon—whose mother fell in love with another woman when Noxon was 13 years old—was unable to read some of the mail the writing team received because it was so upsetting. To her, the pain expressed in viewers' letters was a logical reaction to the lack of realistic lesbian role models on television.[38]

Willow's cultural impact has been noted in several other ways. Patrick Krug, a biologist at California State University, Los Angeles named a sea slug with traits of sexual flexibility Alderia willowi partly for his grandmother and partly after Willow's character.[87] Willow was included in AfterEllen.com's Top 50 Lesbian and Bisexual Characters, ranking at No. 7.[88] She was also ranked No. 12 in their Top 50 Favorite Female TV Characters.[89] UGO.com named her one of the best TV nerds.[90] AOL also listed her as the #1 TV witch of all time, and one of the 100 Most Memorable Female TV Characters.[91]

See also

[edit]- Willow & Tara (Buffy comic)

- Unnatural Selection (Buffy novel)

- Deep Water (Buffy novel)

- Apocalypse Memories

- LGBT themes in speculative fiction

- Queer horror

Notes

[edit]- ^ The lines are in Greek addressed to Aphrodite, translated as "I beg you, don't overcome my spirit with pain and care, mistress", foreshadowing Willow's conflict between her devotion to Tara and her addiction to magic (Battis).

- ^ Buffy scholar Edwina Bartlem asserts that many of the sexual relationships on Buffy are symbolized. Willow and Tara's tend to be represented by otherworldly passion, "disembodied and spiritual". (Barlem, Edwina [2003]. "Coming out on a Mouth of Hell", Refractory: a Journal of Entertainment Media, 2, p. 16.) Hannigan noted in an interview, "Obviously during a couple spells they are so fucking. I was like, 'This isn't a spell—this is just the sex you can't get away with on television.' "(Epstein, Jeffrey [August 2001] "Alyson's Wonderland", Out, 10 (2), pp. 46–53.)

Citations

[edit]- ^ Bianco, Robert (January 18, 1998). "Cool and Complicated Creator of Buffy the Vampire Slayer Shaking up Plots so as Not to Hit the Same Beats". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. p. G-2.

- ^ Buffy the Vampire Slayer: The Complete Fifth Season; "Casting Buffy" Featurette. (2008) [DVD]. 20th Century Fox.

- ^ "Melanie Lynskey passed on 'Buffy the Vampire Slayer' because she 'wasn't super into' TV at the time". Entertainment Weekly.

- ^ a b Bonka, Larry (January 12, 1998). "Buffymania Sweeps the Land as Ultra-cool Kids Conquer the Un-dead". The Virginian-Pilot. p. E1.

- ^ a b Cox, Ted (May 11, 1999). "Hannigan's Willow becomes a favorite of 'Buffy' fans". Chicago Daily Herald. p. 3.

- ^ Owen, Rob (September 22, 1997). "Teen Life, with a Macabre Twist". The Cleveland Plain Dealer. p. 5E.

- ^ a b Mason, Charlie (May 16, 1998). "Beyond the Impaled Blossoming Wallflower's Appeal is Play to 'Vampire' Buffs". Times-Picayune. p. E1.

- ^ Stafford, p. 72.

- ^ Grahnke, Lon (March 10, 1997). "Biting satire: 'Buffy,' a sly new series, raises the stakes", The Chicago Sun-Times, p. 33.

- ^ Okamoto, David (March 10, 1997). "Transylvania, 90210: 'Buffy' is back with bite in stylish new WB series". The Dallas Morning News. p. 15A.

- ^ Whedon, Joss (2008). Buffy the Vampire Slayer: The Complete First Season; "DVD Commentary for "Welcome to the Hellmouth" [DVD]. 20th Century Fox.

- ^ Jowett, p. 38.

- ^ Golden and Holder, p. 29.

- ^ Rohan, Virginia (February 23, 1999). "The Dark Side of the Good Friend". The Record. p. Y01. Retrieved October 20, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jarvis, Christopher; Barr, Viv (August 1, 2005). "Friends are the family we choose for ourselves: Young people and families in the TV series Buffy the Vampire Slayer". Nordic Journal of Youth Research. 13 (3). Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications: 269–283.

- ^ Kaveney, pp. 284–286.

- ^ Kaveney, pp. 287–291.

- ^ Stevenson, pp. 128–130.

- ^ Kaveney, pp. 293–295.

- ^ Kaveney, pp. 295–300.

- ^ Kaveney, pp. 300–304.

- ^ Kaveney, p. 242.

- ^ Interview with Buffy creator Joss Whedon 3/26/07 Archived March 26, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Dark Horse Comics. Retrieved on August 17, 2010.

- ^ a b c Vary, Adam (January 19, 2011). Joss Whedon talks about the end of the 'Buffy the Vampire Slayer' Season 8 comic, and the future of Season 9 -- EXCLUSIVE, Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved on May 12, 2022.

- ^ a b Glendening, Daniel (November 30, 2012). Allie discusses Willow's quest to bring magic back to the Buffyverse, Comic Book Resources. Retrieved on May 12, 2022.

- ^ Stafford, pp. 367–373.

- ^ Whedon, Joss; Moline, Karl (December 2009). Willow: Goddesses and Monsters, Dark Horse Comics.

- ^ Phegley, Kiel (December 10, 2010). Behind Buffy Season 8: "Last Gleaming", Comic Book Resources. Retrieved on May 12, 2022.

- ^ a b c Battis, Jes (2003). "She's Not All Grown Yet": Willow as Hybrid/Hero in Buffy the Vampire Slayer." Archived 2011-07-16 at the Wayback Machine The Online International Journal of Buffy Studies, 8. Retrieved on August 16, 2010.

- ^ South, p. 134.

- ^ Driver, pp. 67–70.

- ^ Stafford, pp. 244–246.

- ^ Richardson and Rabb, p. 60.

- ^ Stevenson, pp. 181–183.

- ^ Yeffeth, p. 131.

- ^ South, p. 139.

- ^ Jowett, pp. 80–82.

- ^ a b c Mangels, Andy (August 20, 2002). "Lesbian sex = death?", The Advocate, 869/870, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Barlem, Edwina (2003). "Coming out on a Mouth of Hell", Refractory: a Journal of Entertainment Media, 2, p. 16.

- ^ Driver, p. 79.

- ^ Driver, p. 81.

- ^ "Two to Go". Buffy the Vampire Slayer.

BUFFY: Willow's got an addictive personality, and she just tasted blood. She could be there already.

ANYA: No. She couldn't, a witch at her level. She can only go airborne. (they stop walking and look at her) It's a thing. More flashy, impresses the locals, but it does take longer.

XANDER: Longer than what?

ANYA: Teleporting. - ^ Ruditis, pp. 145–153.

- ^ Zacharek, Stephanie (May 22, 2002). Willow, destroyer of worlds, Salon. Retrieved on May 12, 2022.

- ^ Yeffeth, p. 132.

- ^ a b South, p. 143–144.

- ^ Jowett, p. 60.

- ^ Jowett, p. 61.

- ^ Wilcox and Lavery, pp. 46–56.

- ^ Kaveney, p. 26.

- ^ Waggoner, pp. 10–11.

- ^ a b Richardson and Rabb, p. 92.

- ^ Richardson and Rabb, p. 94.

- ^ Jowett, pp. 124–127.

- ^ South, p. 138.

- ^ a b Stafford, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Perigard, Mark (May 18, 1999). "Television; 'Buffy' promises finale with bite and takes high-stakes gamble", The Boston Herald, p. 44.

- ^ "Interview: Writer and producer Joss Whedon discusses his career and his latest show, 'Buffy the Vampire Slayer'", Fresh Air, National Public Radio (May 9, 2000).

- ^ a b McDaniel, Mike (May 16, 2000). "Coming Out on 'Buffy': Willow discovers she's attracted to another woman, Tara", Houston Chronicle, p. 6.

- ^ Stafford, p. 73.

- ^ Driver, p. 74.

- ^ McAvan, Em (2007). “I Think I’m Kinda Gay”: Willow Rosenberg and the Absent/Present Bisexual in Buffy the Vampire Slayer Archived 2011-07-17 at the Wayback Machine Slayage Online: The Online International Journal of Buffy Studies. Retrieved March 13, 2011.

- ^ Lavery and Wilcox, pp. 45–60.

- ^ a b Ford, Jessica (March 10, 2011). Coming Out of the Broom Closet: Willow's Sexuality and Empowerment in 'Buffy'. PopMatters. Retrieved on May 12, 2022.

- ^ Bianculli, David (May 2, 2000). "Buffy Character Follows Her Bliss", New York Daily News, p. 77.

- ^ "Star stakes out Sydney", Sunday Telegraph (November 5, 2000), p. 31.

- ^ Dudley, Jennifer (November 16, 2000). "Charmed, I'm Sure", Courier Mail (Brisbane, Australia), p. 7.

- ^ Driver, p. 75–76.

- ^ Jowett, pp. 56–57.

- ^ Wilcox and Lavery, p. 58.

- ^ Kaveney, p. 207.

- ^ Jowett, p. 52–53.

- ^ Kaveney, p. 44.

- ^ Ruditis, pp. 205–229.

- ^ Warn, Sarah (April 3, 2003). ""Buffy" to Show First Lesbian Sex Scene on Broadcast TV". AfterEllen. Retrieved October 27, 2014.

- ^ Waggoner, p. 9.

- ^ Hill, Shawn (January 24, 2011). Buffy the Vampire Slayer #40 Archived January 30, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Comics Bulletin. Retrieved on January 30, 2011.

- ^ Driver, p. 62.

- ^ Jowett, p. 58.

- ^ Pateman, Matthew (2007). "'That Was Nifty': Willow Rosenberg Saves the World in Buffy the Vampire Slayer", Shofar: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Jewish Studies, 25 (4). pp. 64-77.

- ^ Hannania, Joseph (March 7, 1999). "Playing Princesses, Punishers and Prudes", The New York Times, p. 35.

- ^ Driver, pp. 58–59.

- ^ Scott, Manda (August 17, 2002). "If the Buffy generation turns out an excess of teenage dykes, I'll be happy but surprised", The Herald, p. 5. Retrieved May 12, 2022

- ^ a b Epstein, Jeffrey (August 2001) "Alyson's Wonderland", Out, 10 (2), pp. 46–53.

- ^ Daly, Sean (November 11, 2000). "Ellen's children: No doubt, this is the Year of the Queer, with an unprecedented 23 prime-time programs featuring homosexual characters.", National Post, p. W06.

- ^ Hoffman, Bill (January 3, 2001). "Magazine Hails Gutsy Gals who 'Bold' Us Over". New York Post. p. 3. Archived from the original on February 17, 2016. Retrieved May 12, 2022.

- ^ Variable Larval Development Modes (poecilogony), California State University, Los Angeles Krug Labs. Retrieved on August 17, 2010.

- ^ "AfterEllen.com's Top 50 Lesbian and Bisexual Characters". AfterEllen. March 15, 2010. Archived from the original on January 1, 2013. Retrieved June 16, 2012.

- ^ "AfterEllen.com's Top 50 Favorite Female TV Characters". AfterEllen.com. February 27, 2012. Archived from the original on January 16, 2013. Retrieved June 24, 2012.

- ^ "Best TV Nerds". UGO Networks. March 7, 2012. Archived from the original on March 9, 2012. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ^ Potts, Kim (March 2, 2011). "100 Most Memorable Female TV Characters". AOL TV. Archived from the original on May 31, 2013. Retrieved July 16, 2012.

Bibliography

[edit]- Driver Susan (2007). Queer Girls and Popular Culture: Reading, Resisting, and Creating Media, Peter Lang. ISBN 0-8204-7936-5

- Golden, Christopher; Holder, Nancy (1998). Buffy the Vampire Slayer: The Watcher's Guide, Volume 1, Pocket Books. ISBN 0-671-02433-7

- Jowett, Lorna (2005). Sex and the Slayer: A Gender Studies Primer for the Buffy Fan, Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 978-0-8195-6758-1

- Kaveney, Roz (ed.) (2004). Reading the Vampire Slayer: The New, Updated, Unofficial Guide to Buffy and Angel, Tauris Parke Paperbacks. ISBN 1-4175-2192-9

- Richardson, J. Michael; Rabb, J. Douglas (2007). The Existential Joss Whedon: Evil and Human Freedom in Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Angel, Firefly and Serenity, McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-2781-7

- Ruditis, Paul (2004). Buffy the Vampire Slayer: The Watcher's Guide, Volume 3, Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-689-86984-3

- South, James (ed.) (2003). Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Philosophy: Fear and Trembling in Sunnydale, Open Court Books. ISBN 0-8126-9531-3

- Stafford, Nikki (2007). Bite Me! The Unofficial Guide to Buffy the Vampire Slayer, ECW Press. ISBN 978-1-55022-807-6

- Stevenson, Gregory (2003). Televised Morality: The Case of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Hamilton Books. ISBN 0-7618-2833-8

- Waggoner, Erin (2010). Sexual Rhetoric in the Works of Joss Whedon: New Essays, McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-4750-8

- Wilcox, Rhonda (2005). Why Buffy Matters: The Art of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, I. B. Tauris. ISBN 1-84511-029-3

- Wilcox, Rhonda and Lavery, David (eds.) (2002). Fighting the Forces: What's at Stake in Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 0-7425-1681-4

- Yeffeth, Glenn (ed.) (2003). Seven Seasons of Buffy: Science Fiction and Fantasy Authors Discuss Their Favorite Television Show, Benbella Books. ISBN 1-932100-08-3

Further reading

[edit]- Angel (1999 TV series) characters

- Buffyverse characters who use magic

- Buffy the Vampire Slayer characters

- Fictional characters who use magic

- Comics about magic

- Fictional American Jews

- Fictional Jews

- Female characters in comics

- American female characters in drama television series

- Television characters introduced in 1997

- Fictional characters from the 20th century

- Fictional characters who can teleport

- Fictional college students

- Fictional hackers

- Fictional lesbians

- Fictional LGBTQ characters in drama television series

- Fictional female murderers

- Fictional telekinetics

- Fictional telepaths

- Fictional vampire hunters

- Teenage characters in drama television series

- Television sidekicks

- Television shows about witchcraft

- Dark Horse Comics female superheroes

- Fictional members of secret societies

- Fictional demon hunters

- Fictional bibliophiles

- Lesbian vampire media