Uruz Project

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

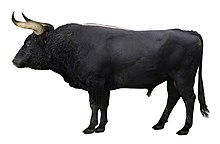

The Uruz Project had the goal of breeding back the extinct aurochs (Bos p. primigenius). Uruz is the old Germanic word for aurochs. The Uruz Project was initiated in 2013 by the True Nature Foundation[1] and presented at TEDx DeExtinction, a day-long conference[2] organised by the Long Now Foundation with the support of TED and in partnership with National Geographic Society,[3] to showcase the prospects of bringing extinct species back to life. The de-extinction movement itself is spearheaded by the Long Now Foundation.

Technically, Bos primigenius is not wholly extinct. The wild subspecies B. p. primigenius, indicus and africanus are, but the species is still represented by domestic cattle. Most, or all, of the relevant Aurochs characteristics, and therefore the underlying DNA, needed to "breed back" an aurochs-like cattle type can be found in B. p. taurus. Domestic cattle originated in the middle east, and there also has been introgression of European aurochs into domestic cattle in ancient times.[4] The Uruz Project's goal is to collect all relevant data and reunite scattered aurochs characteristics, and thus DNA, in one animal.

Background

[edit]

Ecological restoration projects cannot be complete without bringing back those key elements that help shape and reshape wild landscapes. The European aurochs (Bos p. primigenius) was a large and long-horned wild bovine herbivore that existed from the most western tip of Europe until Siberia in present-day Russia. Aurochs have played a major role in human history. They are often depicted in rock-art, including the famous, well-conserved cave paintings made by Cro-Magnon people in the Lascaux Caves, estimated to be 17,300 years old. Aurochs and other large animals portrayed in Paleolithic cave art were often hunted for food. Hunting and habitat loss caused by humans, including agricultural land conversion, caused the aurochs to go extinct in 1627, when the last individual, a female, died in Poland’s Jaktorów Forest.[5]

The aurochs is one of the keystone species that is missing in Europe. Their grazing and browsing patterns, trampling of the soil and faeces had a profound impact on the vegetation and landscapes it inhabited. Grazing results in a greater variety of plant species, structures and ecological niches in a landscape that benefit both biodiversity and production.[6] Megaherbivores like the aurochs also controlled vegetation development.[7]

Breeding strategy

[edit]The Uruz Project aims to breed an aurochs-like breed of cattle from a limited number of carefully selected primitive cattle breeds with known Aurochs characteristics. The project uses Sayaguesa cattle, Maremmana primitiva or Hungarian grey cattle, Chianina and Watusi. The genome of the Aurochs has been completely reconstructed and serves as the baseline for the reconstruction of the Aurochs.[4][8]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Uruz Project". True Nature Foundation. October 2013. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

- ^ "TEDxDeExtinction". TED.

- ^ "De-Extinction : Bringing Extinct Species Back to Life". National Geographic. Archived from the original on March 10, 2013.

- ^ a b Edwards, CJ; Magee DA, Park SD, McGettigan PA, Lohan AJ, Murphy A, Finlay EK, Shapiro B, Chamberlain AT, Richards MB, Bradley DG, Loftus BJ, MacHugh DE.; Park, S. D.; McGettigan, P. A.; Lohan, A. J.; Murphy, A; Finlay, E. K.; Shapiro, B; Chamberlain, A. T.; Richards, M. B.; Bradley, D. G.; Loftus, B. J.; Machugh, D. E. (2010). "A complete mitochondrial genome sequence from a mesolithic wild aurochs (Bos primigenius)". PLOS ONE. 5 (2): e9255. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...5.9255E. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0009255. PMC 2822870. PMID 20174668.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tikhonov, A. (30 June 2008). "Bos primigenius. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species". IUCN.

- ^ Iain J. Gordon; Herbert H. T. Prins (2008). The Ecology of Browsing and Grazing. Springer. pp. 263–292. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-72422-3_10. ISBN 978-3-540-72421-6.

- ^ Jill, JL (2014). "Ecological impacts of the late Quaternary megaherbivore extinctions". The New Phytologist. 201 (4): 1163–1169. doi:10.1111/nph.12576. PMID 24649488.

- ^ Stephen D.E. Park, David E. MacHugh; David A. Magee, Paul A. McGettigan, Matthew Teasdale, Ceiridwen J. Edwards, Amanda J. Lohan, Alison Murphy, Yuan Liu, Emma K. Finlay, Steven G. Schroeder, Daniel G. Bradley, Tad S. Sonstegard, Brendan J. Loftus (January 11–16, 2013). "A Complete Nuclear Genome Sequence from the Extinct Eurasian Wild Aurochs (Bos primigenius)". Plant and Animal Genome XXI Conference, San Diego, CA. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

[edit]- Aurochs at the True Nature Foundation

- Long Now Foundation

- Uruz Project on Facebook