Uriankhai

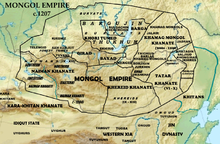

Mongol Empire c. 1207, Uriankhai and their neighbours | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| 26,654 (2010 census)[1] | |

| Languages | |

| Oirat, Mongolian | |

| Religion | |

| Buddhism, Mongolian shamanism, Atheism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Mongols, especially Oirats | |

Uriankhai /ˈʊriənxaɪ/[a] is a term of address applied by the Mongols to a group of forest peoples of the North, who include the Turkic-speaking Tuvans and Yakuts, while sometimes it is also applied to the Mongolian-speaking Altai Uriankhai. The Uriankhai included the western forest Uriankhai tribe and the Transbaikal Uriankhai tribe, with the former recorded in Chinese sources as Chinese: 兀良哈; pinyin: Wùliánghā). It is also the origin of the Korean term "olangkae", 오랑캐, meaning barbarian.

History

[edit]The name "Uriankhai' means "uria" (motto, war motto) and khan (lord) in Mongolian. The Mongols applied the name to all the forest peoples and, later, to Tuvans. They were classified by the Mongols as Darligin Mongols.

At the beginning of the Mongol Empire (1206–1368), the Uriankhai were located in central Mongolia.

In 13th century Yuan China, Rashid-al-Din Hamadani described the Forest Uriyankhai as extremely isolated Siberian forest people living in birch bark tents and hunting on skis. Despite the similarity in name to the famous Uriyankhan clan of the Mongols, Rashid states that they had no connection.[2] During the Ming dynasty, the Jurchens were known among the Chinese as "forest people" (using the Jurchen word, Woji), and this connotation later transferred to the Chinese rendering of Uriankhai, Wulianghai.[3]

In the mid-14th century, they lived in Liaoyang in Northeast China. In 1375, Naghachu, Uriankhai leader of the Mongol-led Northern Yuan dynasty in Liaoyang, invaded the Liaodong Peninsula to restore the Mongols to power. Although he continued to hold southern Manchuria, the Ming military campaign against Naghachu ended with his surrender in 1388.[4] After the rebellion of the northern Uriankhai people, they were conquered by Dayan Khan in 1538 and mostly annexed by the northern Khalkha. Batmunkh Dayan Khan dissolved Uriankhai tumen.

The second group of Uriankhai (Uriankhai of the Khentii Mountains) lived in central Mongolia and they started moving to the Altai Mountains in the beginning of the 16th century.[5] Some groups migrated from the Khentii Mountains to Khövsgöl Province during the course of the Northern Yuan dynasty (1368–1635).[3]

By the early 17th century the term Uriankhai was a general Mongolian term for all the dispersed bands to the northwest, whether Samoyedic, Turkic, or Mongol in origin.[2] In 1757 the Qing dynasty organized its far northern frontier into a series of Uriankhai banners: the Khövsgöl Nuur Uriankhai, Tannu Uriankhai; Kemchik, Salchak, and Tozhu (all Tuvans); and Altai people. Tuvans in Mongolia are called Monchoogo Uriankhai (cf. Tuvan Monchak < Kazakh monshak "necklace") by Mongolians. Another group of Uriankhai in Mongolia (in Bayan-Ölgii and Khovd Provinces) are called Altai Uriankhai. These were apparently attached to the Oirats. A third group of Mongolian Uriankhai were one of the 6 tumens of Dayan Khan in Eastern Mongolia. These last two Uriankhai groups are said to be descendants of the Uriankhan tribe from which came Jelme and his more famous cousin Subutai. The clan names of the Altai Uriankhai, Khövsgöl Nuur Uriankhai and Tuvans are different. There are no Turkic or Samoyedic clans among the Altai or Khövsgöl Uriankhais.

A variation of the name, Uraŋxai Sakha, was an old name for the Yakuts.[6] Russian Pavel Nebolsin documented the Urankhu clan of Volga Kalmyks in the 1850s.[7] The existence of the Uriankhai was documented by the Koreans, who called them by the borrowed name Orangkae (오랑캐, "savages"), especially in context of their attacks against the Siniticized world in the 14th and 15th centuries.[3]

Some Uriankhais still live in the Khentii Mountains.

The Taowen, Huligai, and Wodolian Jurchen tribes lived in the area of Heilongjiang in Yilan during the Yuan dynasty when it was part of Liaoyang province and governed as a circuit. These tribes became the Jianzhou Jurchens in the Ming dynasty and the Taowen and Wodolian were mostly real Jurchens. In the Jin dynasty, the Jin Jurchens did not regard themselves as the same ethnicity as the Hurka people who became the Huligai. Uriangqa was used as a name in the 1300s by Jurchen migrants in Korea from Ilantumen because the Uriangqa influenced the people at Ilantumen.[8][9][10] Bokujiang, Tuowulian, Woduolian, Huligai, Taowan separately made up 10,000 households and were the divisions used by the Yuan dynasty to govern the people along the Wusuli river and Songhua area.[11][12]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Mongolian: ᠤᠷᠢᠶᠠᠩᠬᠠᠢ / Урианхай, romanized: Uriankhai, pronounced [ˌo̙ɾʲæɴˈχæe̯]; Tuvan: Урааңкай, romanized: Urâñkay, pronounced [ʊɾäːɴˈqʰäɪ̯]; Altay: Ураҥкай, romanized: Urañqay, pronounced [ʊrɑɴˈqʰɑj]; Yakut: Урааҥхай, romanized: Urâñxay, pronounced [ʊɾɑːɴˈq͡χɑj]; traditional Chinese: 烏梁海; simplified Chinese: 乌梁海; pinyin: Wūliánghǎi

References

[edit]- ^ National Census 2010

- ^ a b C.P.Atwood Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire, 2004 ISBN 0816046719 ISBN 978-0816046713 p.9

- ^ a b c Crossley, Pamela Kyle (December 1985). "An Introduction to the Qing Foundation Myth". Late Imperial China. 6 (2): 13–24. doi:10.1353/late.1985.0016. S2CID 143797249.

- ^ Willard J. Peterson, John King Fairbank, Denis Twitchett- The Cambridge History of China, vol7, p.158

- ^ A.Ochir, Ts.Baasandorj "Custom of the Oirat wedding". 2005

- ^ POPPE, Nicholas (1969). "Review of Menges "The Turkic Languages and Peoples"". Central Asiatic Journal. 12 (4): 330.

- ^ Mänchen-Helfen, Otto (1992) [1931]. Journey to Tuva. Los Angeles: Ethnographic Press University of Southern California. p. 180. ISBN 1-878986-04-X.

- ^ Chʻing-shih Wen-tʻi. Chʻing-shih wen-tʻi. 1983. p. 33.

- ^ Ch'ing-shih Wen-t'i. Ch'ing-shih wen-t'i. 1983. p. 33.

- ^ Pamela Kyle Crossley (15 February 2000). A Translucent Mirror: History and Identity in Qing Imperial Ideology. University of California Press. pp. 200, 75. ISBN 978-0-520-92884-8.

- ^ Yin Ma (1989). China's minority nationalities. Foreign Languages Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-8351-1952-8.

- ^ Tadeusz Dmochowski (2001). Rosyjsko-chińskie stosunki polityczne: XVII-XIX w. Wydawn. Univ. p. 81. ISBN 978-83-7017-986-1.