Urbana, Illinois

Urbana, Illinois | |

|---|---|

Carle Park | |

Interactive map of Urbana | |

| Coordinates: 40°06′38″N 88°11′50″W / 40.11056°N 88.19722°W[1] | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Illinois |

| County | Champaign |

| Founded | 1833 |

| Named for | Urbana, Ohio, U.S. |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–council |

| • Mayor | Diane Wolfe Marlin (D) |

| Area | |

| • City | 11.90 sq mi (30.83 km2) |

| • Land | 11.83 sq mi (30.64 km2) |

| • Water | 0.07 sq mi (0.19 km2) |

| Elevation | 732 ft (223 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • City | 38,336 |

| • Density | 3,240.57/sq mi (1,251.15/km2) |

| • Metro | 236,072 |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| Postal code | 61801–61803 |

| Area codes | 217, 447 |

| FIPS code | 17-77005 |

| GNIS ID | 2397097[1] |

| Website | urbanaillinois |

Urbana (/ɜːrˈbænə/ ur-BAN-ə) is a city in and the county seat of Champaign County, Illinois, United States.[3] As of the 2020 census, Urbana had a population of 38,336. It is a principal city of the Champaign–Urbana metropolitan area, which had 236,000 residents in 2020.

Urbana is notable for sharing the main campus of the University of Illinois with its twin city of Champaign.

History

[edit]The Urbana area was first settled by Europeans in 1822,[4] when it was called "Big Grove".[5] When the county of Champaign was organized in 1833, the county seat was located on 40 acres of land, 20 acres donated by William T. Webber and 20 acres by M. W. Busey, considered to be the city's founder, and the name "Urbana" was adopted[4] after Urbana, Ohio, the hometown of State Senator John W. Vance, who authored the Enabling Act creating Champaign County.[6] The creation of the new town was celebrated for the first time on July 4, 1833.[5]

Stores began opening in 1834. The first mills were founded in c. 1838-50. The town's first church, the Methodist Episcopal Church, and the parsonage, was built in 1840 by the Rev. A. Bradshaw, with the Baptist Church following in 1855. The Presbyterian Church was founded in 1856.[7] The city's first school was built in 1854.[4]

Urbana suffered a setback when the Chicago branch of the Illinois Central Railroad, which had been expected to pass through town, was instead laid down two miles west, where the land was flatter. The town of West Urbana grew up around the train depot built there in 1854, and in 1861 its name was changed to Champaign. The competition between the two cities provoked Urbana to tear down the ten-year-old County Courthouse and replace it with a much larger and fancier structure, to ensure that the county seat would remain in Urbana.[5]

Champaign-Urbana was selected as the site for a new state agricultural school, thanks to the efforts of Clark Griggs. Illinois Industrial University, which would evolve into the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, opened in 1868 with 77 students.[5]

A number of efforts to merge Urbana and Champaign have failed at the polls.[5]

On October 9, 1871, a fire burned much of downtown Urbana.[8] Children playing with matches started the fire.[9] (It is unrelated to the Great Chicago Fire that started the day before, though both fires occurred during severe drought and were spread by high winds.)

Geography

[edit]According to the 2021 census gazetteer files, Urbana has a total area of 11.90 square miles (30.82 km2), of which 11.83 square miles (30.64 km2) (or 99.40%) is land and 0.07 square miles (0.18 km2) (or 0.60%) is water.[10]

Urbana borders the city of Champaign. The main campus of the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign is situated on this border. Together, these two cities are often referred to as Urbana-Champaign (the designation used by the university) or Champaign-Urbana (the more common usage, due to the larger size of Champaign). With the nearby village of Savoy they form the Champaign–Urbana metropolitan area.

| Climate data for Urbana, Illinois (1981–2010 normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 70 (21) |

72 (22) |

85 (29) |

95 (35) |

97 (36) |

103 (39) |

109 (43) |

102 (39) |

102 (39) |

93 (34) |

80 (27) |

71 (22) |

109 (43) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 32.9 (0.5) |

37.7 (3.2) |

49.9 (9.9) |

62.8 (17.1) |

73.4 (23.0) |

82.5 (28.1) |

85.0 (29.4) |

83.7 (28.7) |

78.2 (25.7) |

65.2 (18.4) |

50.6 (10.3) |

36.7 (2.6) |

61.7 (16.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 16.7 (−8.5) |

20.2 (−6.6) |

30.0 (−1.1) |

41.1 (5.1) |

51.6 (10.9) |

61.9 (16.6) |

64.9 (18.3) |

63.1 (17.3) |

54.2 (12.3) |

42.6 (5.9) |

32.0 (0.0) |

21.2 (−6.0) |

41.7 (5.4) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −25 (−32) |

−25 (−32) |

−5 (−21) |

15 (−9) |

26 (−3) |

34 (1) |

41 (5) |

37 (3) |

24 (−4) |

12 (−11) |

−5 (−21) |

−20 (−29) |

−25 (−32) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.02 (51) |

2.13 (54) |

2.85 (72) |

3.68 (93) |

4.89 (124) |

4.28 (109) |

4.70 (119) |

3.93 (100) |

3.13 (80) |

3.26 (83) |

3.66 (93) |

2.73 (69) |

41.25 (1,048) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 7.0 (18) |

6.0 (15) |

2.4 (6.1) |

0.4 (1.0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.8 (2.0) |

6.4 (16) |

23.3 (59) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 9.3 | 8.9 | 10.6 | 11.9 | 12.2 | 10.3 | 10.0 | 9.4 | 7.7 | 9.5 | 10.2 | 10.6 | 120.6 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 5.3 | 4.1 | 2.2 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 18.1 |

| Source: NOAA (extremes 1888–present)[11] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 210 | — | |

| 1860 | 1,370 | 552.4% | |

| 1870 | 2,277 | 66.2% | |

| 1880 | 2,942 | 29.2% | |

| 1890 | 3,511 | 19.3% | |

| 1900 | 5,728 | 63.1% | |

| 1910 | 8,245 | 43.9% | |

| 1920 | 10,244 | 24.2% | |

| 1930 | 13,060 | 27.5% | |

| 1940 | 14,064 | 7.7% | |

| 1950 | 22,834 | 62.4% | |

| 1960 | 27,294 | 19.5% | |

| 1970 | 33,976 | 24.5% | |

| 1980 | 35,978 | 5.9% | |

| 1990 | 36,344 | 1.0% | |

| 2000 | 36,395 | 0.1% | |

| 2010 | 41,250 | 13.3% | |

| 2020 | 38,336 | −7.1% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[12] | |||

As of the 2020 census[13] there were 38,336 people, 17,295 households, and 6,680 families residing in the city. The population density was 3,220.97 inhabitants per square mile (1,243.62/km2). There were 18,321 housing units at an average density of 1,539.32 per square mile (594.33/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 51.61% White, 18.86% African American, 0.30% Native American, 18.26% Asian, 0.03% Pacific Islander, 3.57% from other races, and 7.37% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 8.52% of the population.

There were 17,295 households, out of which 17.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 25.57% were married couples living together, 8.99% had a female householder with no husband present, and 61.38% were non-families. 44.42% of all households were made up of individuals, and 8.10% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.70 and the average family size was 2.06.

The city's age distribution consisted of 11.7% under the age of 18, 38.2% from 18 to 24, 26.1% from 25 to 44, 13.4% from 45 to 64, and 10.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 25.0 years. For every 100 females, there were 97.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 97.2 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $35,984, and the median income for a family was $66,955. Males had a median income of $27,150 versus $25,511 for females. The per capita income for the city was $25,365. About 11.4% of families and 29.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 19.1% of those under age 18 and 5.6% of those age 65 or over.

Arts and culture

[edit]

Candlestick Lane

[edit]

Candlestick Lane is the name of a neighborhood in eastern Urbana. This neighborhood consists of Grant Place and adjacent properties on Fairlawn and Eastern Drives. It is called Candlestick Lane because every year the residents decorate their yards for Christmas with a lot of lights and figures. The tradition began in 1961 (maybe 1960) as a house-decorating contest sponsored by the Illinois Power Company. The neighborhood used its prize money to purchase electric candlesticks for each home. The City of Urbana installs special red and green street signs, reading "Candlestick Lane" and "Grant Place" during the Holiday season. The lights are turned on from around 5:00 to 10:00 p.m. from the third Saturday in December through New Years Day.[14]

Market at the Square

[edit]

The Market at the Square, also known as the Farmers' Market, has been a community event in Urbana since 1979.[15] Every Saturday morning from some time in May to some time in November, dozens of vendors set up shop in the Lincoln Square parking lot in downtown Urbana. They primarily sell local produce (including corn, tomatoes, lettuce and watermelons), but one can also find local crafts, music, kettle corn and booths for various community and political organizations.

Urbana Sweetcorn Festival

[edit]The Urbana Sweetcorn Festival is an annual festival in Urbana. It was first held in August 1975 in the Busey Bank parking lot in downtown Urbana. It was a community event put on by employees of Busey Bank. Since then the Sweetcorn Festival has continued to grow. The Urbana Business Association is now responsible for the planning of the festival, over the years adding a local car show, an expanded family area, live music on multiple stages, food, vendors, beer, in the heart of downtown Urbana.

In addition to corn and beverages, the festival has offered a range of activities and events, including a display of antique and other collectors' cars and volksmarches, arts events, a dog show, and a book sale organized by the Friends of the Urbana Free Library.[16][17][18]

Urbana Lincoln Hotel

[edit]The Urbana Lincoln Hotel is connected to Lincoln Square Mall, an indoor walking mall, in the center of Urbana. The hotel was designed by famed Urbana architect Joseph Royer in 1923 and opened several rooms on November 1, 1923, to accommodate guests for the university's Homecoming game. The original building was built in the Tudor Revival style. A convention center was added in the 1970s in the Bavarian style. While being forced to close twice between 1990 and 2009, the hotel was purchased by a private developer in 2010 and underwent major rehabilitation. The hotel opened under new management and with a new name, Urbana Landmark Hotel, on December 1, 2012, but it closed in July 2015[19] and sold January 2020 for redevelopment as a Hilton Tapestry hotel.[20]

Points of interest

[edit]- American Football House

- University of Illinois Arboretum

- University of Illinois Conservatory and Plant Collection

- Krannert Center for the Performing Arts

- Spurlock Museum

- Station Theatre

Parks and recreation

[edit]

Carle Park,[21] established in 1909, is located at Indiana and Garfield, just west of Urbana High School in central Urbana. Measuring 8.3 acres (34,000 m2), it contains a statue entitled Lincoln the Lawyer by Lorado Taft and more than 50 well-established trees that are part of the Hickman Tree Walk. The Lincoln statue was previously sited in front of the Urbana Lincoln Hotel, but was moved after only a few months.

Meadowbrook Park[22] is located southeast of the Race Street and Windsor Road intersection. The park covers 130 acres (0.53 km2), including 80 of recreated Illinois tallgrass prairie. Around the prairie restoration center of the park loops three miles of wide concrete path suitable for walking, running, and bicycling. In addition, for an off the beaten path experience, the park offers two miles of unpaved trails which wind through the prairie grass. Several small hills make the path unsuitable for inexperienced inline skaters. The path is adorned by about twenty large sculptures from local artists. A playground, shelter, and parking lot are located near the Windsor Road entrance. A community garden, an herbal garden, the Timpone Ornamental Tree Grove and a shelter are located near the Race Street entrance. The park also contains many streams which are among the first tributaries of the Embarras River.

The Urbana Dog Park,[23] located on East Perkins Road, is a place to walk one's dog without a leash.

The Anita Purves Nature Center, located on the north end of Crystal Lake Park, offers nature education programs.[24]

The "Art in the Park",[25] just north of the Urbana City Hall (400 S. Vine St.) dedicated October 2012, took 22 years of struggle and efforts of three mayors. The environmental and sculptural artists/curator of the park, John David Mooney designed the plantings, walkways, a 12-foot high fountain sculpture (Falling Leaf), and a 33-foot high light sculpture (Spirit Tree). The Spirit Tree specifically gives new meaning to Urbana's designation as a "Tree City" and to trees as landmarks or beacons. Mooney, an internationally acclaimed artist, is a native to Champaign-Urbana.[26]

Swimming pools

[edit]The Urbana Indoor Aquatic Center[27] is a public indoor pool operated by the Urbana Park District and Urbana School District. It is located between Urbana High School and Urbana Middle School.

Crystal Lake Pool[28] is a public outdoor pool. It is located on Broadway Street, across from the Anita Purves Nature Center. It was closed after the summer 2008 season due to deteriorating conditions and concomitant safety issues, it was rebuilt and reopened in 2013.

Campus Recreation Center East (CRCE) has an indoor leisure pool with a hot tub. CRCE is owned by the University of Illinois Urbana–Champaign.[29] In Urbana, the pools in Freer Hall, formerly a 25-yard and 6-lane lap pool, and Kenney Gym have been closed and filled, the former redeveloped as research and teaching spaces.[30]

Sports

[edit]Illinois Fighting Illini

[edit]The University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign fields ten men and eleven women varsity sports.

| Team | Established | Big Ten Conference Titles | NCAA Postseason Appearances | National Titles | Venue | Opened | Capacity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Football | 1890 | 15 | 17 | 5 | Memorial Stadium | 1923 | 60,670 |

| Men's basketball | 1905 | 17 | 30 | 1 | State Farm Center | 1963 | 15,500 |

| Women's basketball | 1974 | 1 | 8 | 0 | State Farm Center | 1963 | 15,500 |

| Baseball | 1879[31] | 29 | 10 | 0 | Illinois Field | 1988 | 3,000 |

| Women's volleyball | 1974 [32] | 4 | 22 | 0 | Huff Hall | 1925 | 4,050 |

| Men's gymnastics | 1898 [33] | 24 | 44 | 10 | Huff Hall | 1925 | 4,050 |

Minor league

[edit]Urbana has been home to several separate minor league baseball clubs in conjunction with Champagin. The Champaign-Urbana Velvets played in the Illinois–Missouri League from 1911 until the league disbanded after 1914.[34] The city's most recent minor league team was the Champaign-Urbana Bandits who played during the single 1994 season of the Great Central League.[35] The Bandits played at Illinois Field. Prior to holding postseason play, the league folded. The Champaign-Urbana Colts played in the Central Illinois Collegiate League from 1990 until the team folded in 1996.[36]

Government

[edit]Urbana has Mayor–council government, of the strong-mayor form. The city council has seven members, each elected from a different ward. The mayor is elected in a citywide vote.

Education

[edit]Primary and secondary

[edit]

Urbana High School's current building was built in 1914. It was designed by architect Joseph Royer who also designed many other area buildings such as the Urbana Free Library and the Champaign County Court House. The architecture is of the Tudor style defined primarily by the towers over the main entrance and flattened point arches over the doors.

Not part of the Urbana School District, University Laboratory High School, locally known as Uni High, is a publicly funded laboratory school located on the campus of the University of Illinois in Urbana. It was founded in 1921. It is a research project of the University of Illinois College of Education.

Urbana Middle School was first known as Urbana Junior High School in 1953. In 2003 the school was renovated for space. The school currently serves 954 students from grades 6 to 8.[37]

The Elementary schools in Urbana are Leal, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Dr. Preston L. Williams Jr., Thomas Paine, and Yankee Ridge. Urbana Early Childhood School is the former Washington Early Childhood Center and is located on the Prairie Campus next to Dr. Preston L. Williams Elementary.

Colleges and universities

[edit]Most of the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign campus lies in this city. It is a public land-grant research university and the flagship institution of the University of Illinois system. It is one of the largest public universities by enrollment in the United States with over 50,000 students enrolled annually, giving Urbana a large student population throughout the year.[38]

Urbana Free Library

[edit]

The Urbana Free Library,[39] one of the first public libraries in Illinois, was founded in 1874 and is located in the downtown area.[40] The historic building which houses the library was built in 1918. A major new addition was opened in 2005.

The library houses historical archives of Champaign County, which can be used for genealogical research. Established in 1956, the Champaign County Historical Archives[41] is a department of the Urbana Free Library that maintains a research-level collection on the history and genealogy of Champaign County. In 1987 it was designated the official repository for non-current Champaign County records. Although it focuses on Champaign County, the Archives holds extensive collections of works dealing with the rest of Illinois and those states that document the significant migration routes of the communities that comprise Champaign County.[41] The CCHA is also home to the Local History Online database.[42] Local History Online gives access to holdings (books and journals, Champaign County records, City of Urbana municipal records, newspapers, directories, school yearbooks, images, maps, oral histories, local organization newsletters, and other special collections) of the Champaign County Historical Archives, including digital content. The catalog is frequently updated.[43]

The library is publicly funded and receives additional support from about 600 people who have joined the Friends of the Urbana Free Library.

Media

[edit]|

FM radio

AM radio |

Analog television

Digital television (DTV)

|

Transportation

[edit]

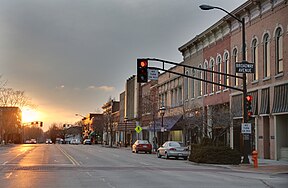

Downtown Urbana is located southwest of the intersection of its two busiest streets: U.S. 150 (University Avenue) and U.S. 45 (Vine Street-Cunningham Avenue).

Most of Urbana lies south of I-74. There are three exits (from west to east): Lincoln (I-74 milepost 183), Cunningham (184) and University (185). The Lincoln exit is closest to the University of Illinois, while the Cunningham exit goes to downtown Urbana. The University exit goes to downtown Urbana as well as Illinois Route 130 to Philo.

Local bus service is primarily provided by the Champaign–Urbana Mass Transit District, although limited service is available from Champaign County Area Rural Transit System and Danville Mass Transit, operators which primarily serve Rantoul and Danville respectively.

The Norfolk Southern operates an east to west line through Urbana. The NS line connects industries in eastern Urbana to the Norfolk Southern main line at Mansfield, Illinois, west of Champaign. The line now operated by Norfolk Southern is the former Peoria & Eastern Railway, later operated as part of the Big Four (Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago and St. Louis Railway), New York Central, Penn Central, and Conrail systems, being sold by Conrail to Norfolk Southern in 1996. Construction of the line was begun by the Danville, Urbana, Bloomington and Pekin Railroad. This short-lived entity became part of the Indianapolis, Bloomington and Western Railway before the railroad was completed. A branch line of the Norfolk and Western Railway (formerly the Wabash Railroad) used to connect Urbana with the main line from Danville to Decatur at Sidney, Illinois, but this was first rerouted and later closed in the early 1990s.

University of Illinois Willard Airport serves the city.

In popular culture

[edit]In the 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey, Urbana was named as the location where the HAL 9000 computer of the ill-fated Discovery Mission to Jupiter was programmed. The 1959 comedy Some Like It Hot also mentions Urbana. Near the beginning of this film, Jack Lemmon's character, an unemployed bass player, suggests to Tony Curtis, a saxophone player, that the two visit Urbana to play at the University of Illinois. Instead, the two musicians elected to join a women's band in Florida. Urbana provides the setting for Bert I. Gordon's 1957 science fiction film, Beginning of the End. Parodied on the television program, Mystery Science Theater 3000, this movie features the unintentional creation of dangerous, giant grasshoppers as a result of agricultural research gone awry.

University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign English Professor and National Book Award winner Richard Powers set his novel Galatea 2.2 at the multidisciplinary Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology. Spanish writer Javier Cercas uses Urbana as the geographical background for two of his novels, "La velocidad de la luz" (2005) and "El inquilino" (1989).

The "American Football House", which is famously pictured on emo band American Football's albums, is located at 704 West High Street.[44][45][46]

Sister cities

[edit]

Urbana is twinned with three sister cities:

- Zomba, Malawi[47]

- Haizhu, Guangzhou, China

- Thionville, France

The city of Urbana has been awarded a major grant from Sister Cities International to undertake a trilateral pilot project involving Urbana, Zomba, Malawi, and the Haizhu District, China. The one-year Sino-African Initiative grant is for up to $100,000 and will involve a collaborative effort to improve the municipal waste disposal system in Zomba, a city of 88,000 in southeast Africa. Urbana has had a Sister City relationship with Zomba since 2008, another relationship with Haizhu District, Guangzhou City, China since 2012, and added a third sister city charter with Thionville, France in 2014. Urbana is one of only three cities in the United States to be awarded a Sino-African grant. The others are Denver and an Asheville/Raleigh, N.C., joint team application.

Notable people

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Urbana, Illinois

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 15, 2022.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on July 12, 2012. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ a b c "History of the City of Urbana". Retrieved October 13, 2007.[dead link]

- ^ a b c d e McGinty, Alice. "The Story of Champaign-Urbana" Archived 2016-02-14 at the Wayback Machine Champaign Public Library

- ^ "John W. Vance: The "Father of Champaign County" | Urbana Free Library". urbanafreelibrary.org. Retrieved February 9, 2022.

- ^ "Our History". December 22, 2018.

- ^ "History of Urbana - Urbana Business AssociationUrbana Business Association". Archived from the original on October 26, 2014. Retrieved October 26, 2014.

- ^ "IAFF Local 1147". Archived from the original on April 25, 2012. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- ^ "Gazetteer Files". Census.gov. Retrieved June 29, 2022.

- ^ "NowData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved February 27, 2012.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved June 28, 2022.

- ^ ""Candlestick Lane Debut" by Tom Kacich, The News-Gazette Weblog".

- ^ "Market at the Square". Archived from the original on July 26, 2007.

- ^ Wilkey, Maureen (August 27, 2004). "Corn festival comes to C-U". Daily Illini. Archived from the original on March 25, 2008. Retrieved April 7, 2008.

- ^ Puhala, Bob (August 9, 1987). "It's time for corny fun at Midwest festivals". Chicago Sun-Times. p. 15. Retrieved April 7, 2008.

- ^ Kline, Greg (August 18, 2003). "Putting the sweet in corn". The News-Gazette. Champaign, Illinois. Retrieved April 7, 2008. [dead link]

- ^ Kacich, Tom. "Hotel back on market". The News-Gazette.

- ^ Zigterman, Ben. "Developer completes purchase of Urbana's Landmark Hotel". The News-Gazette.

- ^ "Carle Park - General Gallery - Photo Galleries | Urbana Park District". www.urbanaparks.org.

- ^ "Meadowbrook Park". urbanaparks.org.

- ^ "Dog Park · Urbana Park District". Archived from the original on November 12, 2007. Retrieved November 26, 2007.

- ^ Urbana Parks

- ^ Art in the Park

- ^ "Home". jdmf.

- ^ "Indoor Aquatic Center - Urbana Indoor Aquatic Center - Photo Galleries | Urbana Park District". www.urbanaparks.org.

- ^ "Family Aquatic Center - Crystal Lake Park Family Aquatic Center - Photo Galleries | Urbana Park District". www.urbanaparks.org.

- ^ "Pools - Campus Recreation". Retrieved January 30, 2019.

- ^ Des Garennes, Christine (January 27, 2015). "Another UI indoor pool closing". The News-Gazette. Retrieved January 30, 2019.

- ^ "Illinois Baseball" (PDF). grfx.cstv.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 28, 2013. Retrieved July 20, 2022.

- ^ "Fighting Illini 2012 Volleyball Prospectus" (PDF). grfx.cstv.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 5, 2012. Retrieved July 20, 2022.

- ^ "2013 University of Illinois Men's Gymnastics" (PDF). grfx.cstv.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 9, 2013. Retrieved July 20, 2022.

- ^ Champaign, Illinois Minor League history. Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved on 2013-08-17.

- ^ 1994 Champaign-Urbana Bandits Statistics – Minor Leagues. Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved on 2013-08-17.

- ^ Mayor wants to explore options for minor league baseball in Champaign. News-Gazette.com (2011-06-26). Retrieved on 2013-08-17.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 29, 2015. Retrieved September 28, 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "UIUC Student Enrollment by Curriculum and Student Level Fall 2023". illinois.edu. University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Retrieved January 3, 2024.

- ^ "| Urbana Free Library". urbanafreelibrary.org.

- ^ "The Urbana Free Library 1874 - Present". Archived from the original on June 22, 2010. Retrieved July 13, 2010.

- ^ a b "Champaign Country Historical Archives". Archived from the original on April 22, 2012. Retrieved May 14, 2012.

- ^ "Local History & Genealogy". Urbana Free Library. Innovative Interfaces.

- ^ "Local History Online". Archived from the original on April 22, 2012. Retrieved May 14, 2012.

- ^ "Emo Tourism: How the American Football House Became One of Music's Biggest Landmarks". www.vice.com. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ "'The American Football House'". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ @21stshow (July 30, 2020). "The American Football House in Urbana". Illinois Public Media. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Urbana's Sister City Program--Zomba, Malawi". Retrieved September 17, 2011.

External links

[edit]- City of Urbana (official website)

- Urbana Free Library

- Champaign-Urbana Historic Built Environment Digital Image Collection

- Urbana Park District – local parks, pools, and other recreation

- Early History of Urbana City[dead link]

- Urbana Business Association

- Champaign Democrat, Google news archive. —PDFs of 1,286 issues, dating from 1887 through 1916.