Urban Cowboy

| Urban Cowboy | |

|---|---|

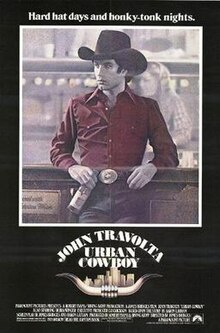

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | James Bridges |

| Screenplay by | James Bridges Aaron Latham |

| Story by | Aaron Latham |

| Produced by | Irving Azoff Robert Evans C. O. Erickson (executive producer) |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Reynaldo Villalobos |

| Edited by | David Rawlins |

| Music by | Ralph Burns |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 135 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $10 million[1] |

| Box office | $53.3 million |

Urban Cowboy is a 1980 American romantic Western film directed by James Bridges. The plot concerns the love-hate relationship between Buford "Bud" Davis (John Travolta) and Sissy (Debra Winger). The film's success was credited for spurring a mainstream revival of country music.[2] Much of the action revolves around activities at Gilley's Club, a football-field-sized honky tonk in Pasadena, Texas.

Plot

[edit]Buford "Bud" Davis leaves his family home in Spur and moves to Pasadena for an oil refinery job where his uncle, Bob Davis, works. Bud wants to earn enough money to buy land in Spur. While staying with Bob and his family, Bud embraces the local nightlife, including Gilley's, a popular Pasadena bar and nightclub.

There, Bud meets fellow nightclub patron, Sissy. They marry soon after and move into a mobile home. They settle into a routine of working during the day and socializing at Gilley's at night. Bud enjoys riding the mechanical bull, but when Sissy wants to try, Bud forbids it.

Wes Hightower, a recently-paroled convict and prison rodeo champion, is hired to operate Gilley's mechanical bull. One evening, a drunken Bud becomes enraged when Wes flirtatiously tips his hat at Sissy. A fight between Bud and Wes starts, with Wes gaining the upper hand. Wanting to impress Bud, Sissy secretly spends time at Gilley's where Wes teaches her how to ride the mechanical bull. When Sissy successfully rides the bull, Bud is angry that she defied him. During Bud's ride, Wes intentionally swings the bull around hard, breaking Bud's arm. At home, Bud and Sissy argue. She claims that Bud is jealous because she rides the bull better than him, causing Bud to slap Sissy and throw her out of their mobile home. Some nights later, Bud sees Sissy at Gilley's and gives her a smile, but she ignores him. Bud retaliates by dancing with Pam, the daughter of a rich oilman. They leave together, with Bud making sure that Sissy sees them. Sissy moves in with Wes, who lives in a run-down trailer behind Gilley's.

Bud, who cannot work while his arm is in a cast, wants to compete in Gilley's upcoming mechanical bull riding rodeo contest for the $5,000 prize. While Bud is training with his uncle, a former rodeo champion, Sissy stops by the mobile home to collect her belongings. While there, she cleans it up and leaves Bud a note saying that she hopes that they will get back together. Pam arrives at the mobile home as Sissy is leaving, and later finds the note which she throws away. Pam then leads Bud to believe that she cleaned the mobile home herself. Sissy returns to Wes's trailer and catches him with Marshalene, a woman who works at Gilley's. After Marshalene leaves, an angry Sissy throws a carton of cigarettes at him and refuses to fix him a meal. In response, Wes beats her.

Bob urges Bud to reconcile with Sissy, citing how his own formerly bad behavior nearly ruined his marriage. Bob later dies in a refinery explosion when a bolt of lightning strikes a tank, devastating Bud. Sissy attends the funeral and tells Bud that Wes was fired from Gilley's and that they plan to leave for Mexico after Wes wins the contest.

Bud initially plans to skip the contest, but changes his mind after his Aunt Corene insists that Bob would have wanted him to go. Down to his last attempt on the mechanical bull, Bud has his best ride and out-scores Wes to win, but is disappointed that Sissy is not present when he is awarded the prize. Pam realizes that Bud still loves Sissy and admits that it was Sissy who cleaned the mobile home. Pam urges Bud to reconcile with Sissy before it is too late. As Sissy waits in her car, Wes sneaks into the Gilley's main office armed with a pistol to steal the entry money. Bud finds Sissy in the parking lot and says that he loves her and apologizes for being stubborn and for hitting her. After they embrace, Bud sees Sissy's bruised face. Furious, he goes after Wes. A fight ensues outside the bar, with Bud getting the upper hand this time. Wes drops his gun, and the stolen entry money falls from his jacket. After the fight, Wes is apprehended, and Sissy swears that she did not know what he was doing. Bud believes her, and they leave to go home together.

Cast

[edit]- John Travolta as Buford Uan "Bud" Davis

- Debra Winger as Sissy

- Scott Glenn as Wes Hightower

- Madolyn Smith as Pam

- Barry Corbin as Bob Davis

- Brooke Alderson as Corene Davis

- Cooper Huckabee as Marshall

- James Gammon as Steve Strange

- Mickey Gilley as himself

- Johnny Lee as himself

- Bonnie Raitt as herself

- Charlie Daniels as himself

- Ellen March as Becky

- Jessie La Rive as Jessie

- Connie Hanson as Marshalene

- Tamara Champlin as Gilley Background Vocalist

- Becky Conway as Gilley Background Vocalist

- Jerry Hall as Sexy Sister

- Cyndy Hall as Sexy Sister

Historical background and production

[edit]The film's screenplay was adapted by Aaron Latham and James Bridges from an article by the same name in Esquire written by Latham. The original Esquire article centered on the romance between two of Gilley's regulars named Dew Westbrook and Betty Helmer. Westbrook and Helmer's relationship became the inspiration for the romance between John Travolta's and Debra Winger's characters "Bud" and "Sissy".[3] The movie was directed by Bridges. Some film critics referred to the movie as a country music version of Saturday Night Fever. The film grossed almost $47 million in the United States alone and represented a temporary recovery for Travolta from 1978's poorly received Moment by Moment, but the film was not nearly as successful as either Saturday Night Fever ($94 million) or Grease ($188 million). While filming Urban Cowboy, Travolta had a private corner at the Westheimer Road location of the Ninfa's restaurant chain in Houston.[4] Urban Cowboy was the first motion picture to be choreographed by Patsy Swayze, which launched her career as a film choreographer.[5]

Critical reception and legacy

[edit]The film received generally positive reviews from critics. On Rotten Tomatoes, the film received a 70% "Fresh" rating based on 23 reviews.[6] "Urban Cowboy is not only most entertaining but also first-rate social criticism," said Vincent Canby of The New York Times.[7] Variety wrote: "Director James Bridges has ably captured the atmosphere of one of the most famous chip-kicker hangouts of all: Gilley's Club on the outskirts of Houston."[8]

The film gave Pasadena and Houston a brief turn under the Hollywood spotlight. Andy Warhol, Jerry Hall and many other celebrities attended the premiere in Houston.[9][10] Mickey Gilley's career was revived after the film release, and the soundtrack started a music movement.[11]

As a result of the film's success, there was a mainstream revival of country music.[2] The term "Urban Cowboy" was also used to describe the soft-core country music of the early 1980s epitomized by Kenny Rogers, Dolly Parton, Johnny Lee, Mickey Gilley, Janie Frickie and other vocalists whose trademarks were mellow sounds of the sort heard in the movie. This sound became a trademark in country music from the early to mid '80s, in which record sales for the genre soared. The ingenious impactful weaving of highly accessible country music into the film's dramatic soundtrack fabric was largely attributable to the skills of music industry impresario Irving Azoff, who co-produced the film with Robert Evans.

Soundtrack

[edit]The film featured a hit soundtrack album spawning numerous Top 10 Billboard Country Singles, such as #1 "Lookin' for Love" by Johnny Lee, #1 "Stand by Me" by Mickey Gilley, #3 (AC chart) "Look What You've Done to Me" by Boz Scaggs, #1 "Could I Have This Dance" by Anne Murray and #4 "Love the World Away" by Kenny Rogers. It also included songs that were hits from earlier years such as #1 "The Devil Went Down to Georgia" by the Charlie Daniels Band and "Lyin' Eyes" by the Eagles. The film is said to have started the 1980s boom in pop-country music known as the "Urban Cowboy Movement", also known as Neo-Country or Hill Boogie. In December 2018, the soundtrack was certified triple platinum by the RIAA for sales of three million copies.[12]

Proposed TV series adaptation

[edit]On May 28, 2015, it was announced that 20th Century Fox Television had teamed with Paramount Television to adapt Urban Cowboy into a television series, and set Craig Brewer to write and direct the pilot, as well as to executive produce the whole series.[13] Chris Levinson was set as the showrunner and would also executive produce the series, along with Robert Evans and Sue Naegle. In December, Fox cancelled the pilot.[14] On February 1, 2022, it was announced that a television adaptation was in development at Paramount+, with James Ponsoldt serving as director and co-writer alongside Benjamin Percy.[15]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Theater Owners Blame Box Office Blues This Summer on Lower Quality of Movies Wall Street Journal 8 July 1980: 15.

- ^ a b "Country Rocker and Fiddler Charlie Daniels Dies at Age 83". NBC. Associated Press. July 6, 2020. Retrieved 2022-12-17.

- ^ "Dew Westbrook: The original Urban Cowboy is still looking for love". Texas Monthly. September 2001. Archived from the original on 2015-06-18. Retrieved 2017-08-09.

- ^ Huynh, Dai (June 18, 2001). "Restaurateur Mama Ninfa dies". Houston Chronicle. p. A1. Archived from the original on 2017-08-10. Retrieved 2017-08-09.

- ^ Kelly, Devin (September 18, 2013). "Patsy Swayze, mother of Patrick Swayze, dies at 86". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 2014-04-24. Retrieved 2017-08-09.

- ^ "Urban Cowboy". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 2017-11-28. Retrieved 2022-08-12.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (June 11, 1980). "John Travolta, Urban Cowboy". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 30, 2021. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- ^ "Review: Urban Cowboy". Variety. December 31, 1979. Retrieved 2017-08-09.

- ^ Lane, Chris (May 8, 2015). "A Look Back at How Gilley's and Urban Cowboy Affected the Houston Area". Houston Press. Archived from the original on 2017-08-10. Retrieved 2017-08-09.

- ^ Hlavaty, Craig (May 20, 2015). "Looking back on the Houston premiere "Urban Cowboy" 35 years later". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on 2017-08-10. Retrieved 2017-08-09.

- ^ Ross, Marissa R. (June 12, 2015). "Inside Country Music's Polarizing 'Urban Cowboy' Movement". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on September 6, 2017. Retrieved September 17, 2017.

- ^ "RIAA – Searchable Database: Urban Cowboy". Recording Industry Association of America. Archived from the original on September 24, 2020. Retrieved January 9, 2019.

- ^ Littleton, Cynthia (May 28, 2015). "Fox Developing 'Urban Cowboy' TV Remake with Craig Brewer, Paramount TV (Exclusive)". Variety. Archived from the original on 2017-06-27. Retrieved 2017-08-09.

- ^ Andreeva, Nellie (December 11, 2015). "'Urban Cowboy' Pilot Not Going Forward At Fox". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on 2017-09-06. Retrieved 2017-08-09.

- ^ White, Peter (February 1, 2022). "'Urban Cowboy' Series Adaptation In The Works At Paramount+". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved February 1, 2022.

External links

[edit]- Urban Cowboy at IMDb

- Urban Cowboy at AllMovie

- Urban Cowboy at the Internet Broadway Database

- Urban Cowboy at Rotten Tomatoes

- Urban Cowboy at Box Office Mojo

- Production: Urban Cowboy – Working in the Theatre Seminar video at American Theatre Wing.org, April 2003

- 1980 films

- 1980 romantic drama films

- American romantic drama films

- Country music films

- 1980s English-language films

- Films directed by James Bridges

- Films set in Houston

- Films shot in Houston

- Paramount Pictures films

- Films based on newspaper and magazine articles

- Films about domestic violence

- Films produced by Robert Evans

- Films scored by Ralph Burns

- Rodeo in film

- 1980s American films

- English-language romantic drama films