Scoop (novel)

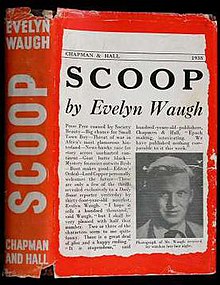

Jacket of the first UK edition | |

| Author | Evelyn Waugh |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Novel |

| Publisher | Chapman & Hall |

Publication date | 1938 |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

| Preceded by | A Handful of Dust |

| Followed by | Put Out More Flags |

| Text | Scoop online |

Scoop is a 1938 novel by the English writer Evelyn Waugh. It is a satire of sensationalist journalism and foreign correspondents.

Summary

[edit]William Boot, a young man who lives in genteel poverty, far from the iniquities of London, contributes nature notes to Lord Copper's Daily Beast, a national daily newspaper. He is dragooned into becoming a foreign correspondent, when the editors mistake him for John Courteney Boot, a fashionable novelist and a remote cousin. He is sent to Ishmaelia, a fictional state in East Africa, to report on the crisis there.

Lord Copper believes it "a very promising little war" and proposes "to give it fullest publicity". Despite his total ineptitude, Boot accidentally gets the journalistic "scoop" of the title. When he returns, the credit goes to the other Boot and William is left to return to his bucolic pursuits, much to his relief.

Background

[edit]The novel is partly based on Waugh's experience of working for the Daily Mail, when he was sent to cover Benito Mussolini's expected invasion of Abyssinia, later known as the Second Italo-Abyssinian War (October 1935 to May 1936). When he got a scoop on the invasion, he telegraphed the story back in Latin for secrecy but they discarded it.[1] Waugh wrote up his travels more factually in Waugh in Abyssinia (1936), which complements Scoop.

Lord Copper, the newspaper magnate, has been said to be an amalgam of Lord Northcliffe and Lord Beaverbrook: a character so fearsome that his obsequious foreign editor, Mr Salter, can never openly disagree with him, answering "Definitely, Lord Copper" and "Up to a point, Lord Copper" in place of "yes" or "no". Lord Copper's idea of the lowliest of his employees is a book reviewer. The historian A. J. P. Taylor wrote, "I have Evelyn Waugh's authority for stating that Lord Beaverbrook was not the original of Lord Copper."[2] Bill Deedes thought that the portrait of Copper exhibited the folie de grandeur of Rothermere and Beaverbrook and included "the ghost of Rothermere's elder brother, Lord Northcliffe. Before he died tragically, deranged and attended by nurses, Northcliffe was already exhibiting some of Copper's eccentricities—his megalomania, his habit of giving ridiculous orders to underlings".[3]

It is widely believed that Waugh based his protagonist, William Boot, on Deedes, a junior reporter who arrived in Addis Ababa aged 22, with "a quarter of a ton of baggage".[4] In his memoir At War with Waugh, Deedes wrote that: "Waugh like most good novelists drew on more than one person for each of his characters. He drew on me for my excessive baggage—and perhaps for my naivety...." He further observed that Waugh was reluctant to acknowledge models, so that with Black Mischief's portrait of a young ruler, "Waugh insisted, as he usually did, that his portrait of Seth, Emperor of Azania, was not drawn from any real person such as Haile Selassie".[5] According to Peter Stothard, a more direct model for Boot may have been William Beach Thomas, "a quietly successful countryside columnist and literary gent who became a calamitous Daily Mail war correspondent".[6]

The novel is full of all but identical opposites: Lord Copper of The Beast, Lord Zinc of the Daily Brute (the Daily Mail and Daily Express); the CumReds and the White Shirts, parodies of Communists (comrades) and Black Shirts (fascists) etc.[3]

Other models for characters (again, according to Deedes): "Jakes is drawn from John Gunther of the Chicago Daily News. In [one] excerpt, Jakes is found writing, 'The Archbishop of Canterbury who, it is well known, is behind Imperial Chemicals...' Authentic Gunther."[7] The most recognisable figure from Fleet Street is Sir Jocelyn Hitchcock, Waugh's portrait of Sir Percival Phillips, working then for The Daily Telegraph.[8] Mrs Stitch is partly based on Lady Diana Cooper, Mr Baldwin is a combination of Francis Rickett and Antonin Besse. Waugh's despised Oxford tutor C. R. M. F. Cruttwell makes his customary cameo appearance, as General Cruttwell.[9]

One of the points of the novel is that even if there is little news happening, the world's media descending requires that something happen to please their editors and owners back home and so they will create news.[10]

Reception

[edit]Christopher Hitchens, introducing the 2000 Penguin Classics edition of Scoop, said "[i]n the pages of Scoop we encounter Waugh at the mid-season point of his perfect pitch; youthful and limber and light as a feather" and noted: "The manners and mores of the press, are the recurrent motif of the book and the chief reason for its enduring magic...this world of callousness and vulgarity and philistinism...Scoop endures because it is a novel of pitiless realism; the mirror of satire held up to catch the Caliban of the press corps, as no other narrative has ever done save Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur's The Front Page."[11]

Scoop was included in The Observer's list of the 100 greatest novels of all time.[12] In 1998, the Modern Library ranked Scoop No. 75 on its list of the 100 best English-language novels of the 20th century.[13]

Adaptations

[edit]In 1972, Scoop was made into a BBC serial: it was adapted by Barry Took, and starred Harry Worth as William Boot and James Beck as Corker.

In 1987, William Boyd adapted the novel into a two-hour TV film, Scoop. Directed by Gavin Millar, it starred Michael Maloney as William Boot and Denholm Elliott as Salter.

In 2009, the novel was serialised and broadcast on BBC Radio 4.

Legacy

[edit]Waugh includes passing mentions of Lord Copper and the Daily Beast in his later novels, Brideshead Revisited (1945) and Officers and Gentlemen (1955).[14][15]

"Feather-footed through the plashy fen passes the questing vole", a line from one of Boot's countryside columns, has become a famous comic example of overblown prose style.[citation needed] It inspired the name of the environmentalist magazine Vole, which was originally titled The Questing Vole.

The fictional newspaper in Scoop served as the inspiration for the title of Tina Brown's online news source, The Daily Beast.[16]

Notes and references

[edit]- ^ Stannard, Martin. Evelyn Waugh: The Early Years, 1903–1939. W. W. Norton & Company, New York 1987, p. 408. ISBN 0-393-02450-4.

- ^ Taylor, Alan John Percivale. Beaverbrook. Hamish Hamilton, London 1972, p. 678.

- ^ a b Deedes, p. 104.

- ^ Deedes, p. 102.

- ^ Deedes, pp. 44, 72.

- ^ "Hay, We got it Wrong". The Times. 29 May 2007. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017.

- ^ Deedes, p. 112.

- ^ Deedes, p. 113.

- ^ Deedes, W. F. (28 May 2003). "The real Scoop: Who was Who in Waugh's Cast List and Why". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- ^ "Evelyn Waugh's 'Scoop': Journalism Is A Duplicitous Business". Archived from the original on 17 June 2013.

- ^ Hitchens, C. Introduction to Scoop. Penguin Classics, London 2000. ISBN 978-0-14-118402-9.

- ^ McCrum, Robert (12 October 2003). "The 100 greatest novels of all time: The list". The Observer.

- ^ "The 100 Best Novels, in English, of the 20th Century". The Modern Library Association.

- ^ Waugh, Evelyn (1962) [1945]. "Book 3, 'A Twitch upon the Thread', Chapter 2". Brideshead Revisited. Harmondsworth: Penguin. p. 253.

- ^ Waugh, Evelyn (1964) [1955]. "Book 2, 'In the Picture', Section 3". Officers and Gentlemen. Harmondsworth: Penguin. p. 154.

- ^ "Tina Brown Launches Much-Awaited News Site". HuffPost. 6 October 2008. Archived from the original on 8 October 2008.

Sources

[edit]- Deedes, William (2003). At War with Waugh. London: Macmillan. ISBN 1-4050-0573-4.

External links

[edit]- Scoop at Faded Page (Canada)

- Read and download the printed book at archive.org