Up Holland

| Up Holland | |

|---|---|

| Village and parish | |

| |

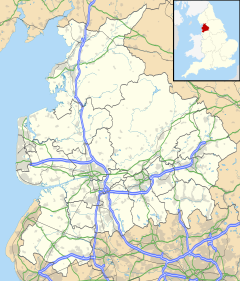

Location within Lancashire | |

| Population | 7,376 (2011) |

| OS grid reference | SD518052 |

| Civil parish |

|

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Skelmersdale |

| Postcode district | WN8 |

| Dialling code | 01695 |

| Police | Lancashire |

| Fire | Lancashire |

| Ambulance | North West |

| UK Parliament | |

Up Holland (or Upholland) is a village in Skelmersdale and is a civil parish in the West Lancashire district, in the county of Lancashire, England, 4 miles (6 km) west of Wigan. The population at the 2011 census was 7,376.[1]

Geography

[edit]The village is on a small hill 89m above sea level[2] that rises above the West Lancashire Coastal Plain. There are views towards St Helens and Liverpool in the south west, Ormskirk and Southport in the north-west and towards Wigan, Manchester and on to the High Peak of Derbyshire in the east. The parish includes the Pimbo industrial estate.

Etymology

[edit]The place-name is first attested in the Domesday Book of 1086, where it appears as Hoiland.[3] It appears as Upholand in a Lancashire Inquest of 1226. This is from the Old English hohland, meaning 'land on or by a hoe or spur of a hill'.[4] The name Up Holland differentiates it from another place locally called Downholland, 10 miles to the west (on the other side of Ormskirk). The manor of Holland was a possession of the Holland family until 1534, whence it may be presumed they derived their name.

Notable claims

[edit]George Lyon, reputed to be one of the last English highwaymen, is said to be buried in the churchyard of the Anglican Church of St. Thomas the Martyr. The truth of the matter is that Lyon was little more than a common thief and receiver of stolen goods. The grave can be found under the concrete parapet opposite the White Lion pub.

A burial place of greater historical significance can be found at the south east corner of the church. Here, in a railed enclosure is the grave of Robert Daglish; a pioneer in steam locomotive engineering and design. In 1814, when George Stephenson was still working on his early locomotive Blucher, Daglish built The Yorkshire Horse,[5] a 'rack and pinion' locomotive to haul coal wagons at a nearby colliery. This proved to be a great success. Daglish went on to construct other locomotives and work on railway systems both in Great Britain and America.

Community

[edit]Up Holland has its own art society known as Upholland Artists' Society[6] that consists of a group of amateur and professional artists that live in or near Up Holland. They hold regular exhibitions and paint a wide range of subjects from local scenes to contemporary abstract pieces.

Upholland railway station is on the Kirkby Branch Line.

Religion

[edit]The church was previously a Benedictine monastery, the Priory of St. Thomas the Martyr of Up Holland.

A Catholic seminary, St Joseph's College, used for training Catholic priests, was once based in Up Holland. The college closed down in 1987 after over 150 years of serving the northern Catholic dioceses of England, and its extensive buildings are now derelict. Notable former students include the historian Paul Addison, community musician Tony Brindle, comedians Tom O'Connor and Johnny Vegas, the libel lawyer George Carman, pop musician Paddy McAloon of Prefab Sprout, the editor of the Jerusalem Bible, and former British Member of Parliament John Battle.

Literature

[edit]Up Holland and its surrounding countryside its described in the English novel The War Hero by Michael Lieber.[7]

People

[edit]Actor Ian Bleasdale and Musician Richard Ashcroft (of The Verve) both come from Up Holland. Richard's mother, Louise, is the daughter of Reg and Lilian Baxter. The Baxters were a prominent family in Up Holland throughout the 20th century. The comedian Ted Ray (born Charles Olden), spent his childhood in the village, his father being the licensee of the Bull's Head public house, which used to stand in School Lane.

The life peer Catherine Ashton, appointed as the European Union's High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy in 2009, was born in Up Holland.[8][9]

The phonetician John C Wells, who was president of the International Phonetic Association between 2003 and 2007, was born in Up Holland to the vicar of the parish, Philip Wells.[10] He has commented on the accent of the area and how it contrasted with the Received Pronunciation that was spoken in his home.[11]

Dorothy Wilkinson (1883-1947) the Australian head teacher[12] and Prof Richard James Arthur Berry, brain surgeon, were born in Up Holland.[13]

Dr Simon Ross Valentine, journalist, lecturer and writer, author of the first book ever published on Peshmerga (Kurdish army fighting ISIS);[14] (for which he was honoured by the Kurdish president with a honorary captaincy in the Kurdish army); writer of the only biography of John Bennet (1714–1759), pioneer Methodist preacher; the Ahmadiyyah Jamaat, reform in Islam and the Globe Award-winning book on Wahhabism, in Saudi Arabia.[15] In 2023 he was commissioned by Bradford Council, West Yorkshire, to write a comprehensive history of Bradford City Hall to mark the Hall's 150th anniversary.[16] He spent his early years in Up Holland, attending the primary school in Roby Mill and Up Holland Grammar School.

Prof Charles Bamforth, brewing expert and football author, was born in Tontine, Up Holland in 1952.

Gallery

[edit]-

Up Holland Windmill

-

The Old Dog pub (formerly The Talbot, now a private residence)

-

St. Thomas Church

-

St Joseph’s College.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ UK Census (2011). "Local Area Report – Up Holland Parish (E04005316)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 26 March 2021.

- ^ "Upholland, Lancashire, United Kingdom - current time, map". Citipedia.info.

- ^ [1] [dead link]

- ^ Eilert Ekwall, The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place-names, p.245.

- ^ "Pingot Valley | The Wigan Archaeological Society". Wiganarchsoc.co.uk. 2 September 2014. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ^ "Fine art, galleries, artist profiles, news, art and paintings". Uphollandartists.com.

- ^ Andrew Nowell (25 June 2019). "Wigan inspired author's debut novel". Wigan Today.

- ^ EU Trade Commissioner Catherine Ashton EU Commission (official website)

- ^ Lady Ashton: Principled, charming ... or just plain lucky Nicholas Watt, Brussels, Guardian.co.uk, Friday 20 November 2009 19.58 GMT

- ^ "J C Wells - personal history". Archived from the original on 5 December 2008. Retrieved 14 August 2008.

- ^ Wells, John (16 March 2012). "John Wells's phonetic blog: English places". Phonetic-blog.blogspot.com.

- ^ Simpson, Caroline, "Dorothy Irene Wilkinson (1883–1947)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, retrieved 7 May 2024

- ^ Russell, K. F. "Berry, Richard James (1867–1962)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University – via Australian Dictionary of Biography.

- ^ "Bradford teacher tells of his experiences in the fight against ISIS on the Iraqi front line". Thetelegraphandargus.co.uk. 19 October 2016.

- ^ "Skelmersdale man publishes book on Saudi life". Southportvisitor.co.uk. 3 August 2015.

- ^ S. R. Valentine, Bradford City Hall: 150 Years of Civic Pride, Bradford Metropolitan District Council, Bradford, 2023