Unknown God

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2011) |

The Unknown God or Agnostos Theos (Ancient Greek: Ἄγνωστος Θεός) is a theory by Eduard Norden first published in 1913 that proposes, based on the Christian Apostle Paul's Areopagus speech in Acts 17:23, that in addition to the twelve main gods and the innumerable lesser deities, ancient Greeks worshipped a deity they called "Agnostos Theos"; that is: "Unknown God", which Norden called "Un-Greek".[1] In Athens, there was a temple specifically dedicated to that god and very often Athenians would swear "in the name of the Unknown God" (Νὴ τὸν Ἄγνωστον, Nē ton Agnōston).[2] Apollodorus,[citation needed] Philostratus[3] and Pausanias wrote about the Unknown God as well.[4]

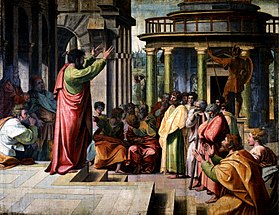

Paul at Athens

[edit]

According to the book of Acts, contained in the Christian New Testament, when the Apostle Paul visited Athens, he saw an altar with an inscription dedicated to that god (possibly connected to the Cylonian affair),[5] and, when invited to speak to the Athenian elite at the Areopagus, gave the following speech:

22Paul stood in the middle of the Areopagus, and said, "You men of Athens, I perceive that you are very religious in all things. 23For as I passed along, and observed the objects of your worship, I found also an altar with this inscription: 'TO AN UNKNOWN GOD.' What therefore you worship in ignorance, this I announce to you. 24The God who made the world and all things in it, he, being Lord of heaven and earth, doesn't dwell in temples made with hands, 25neither is he served by men's hands, as though he needed anything, seeing he himself gives to all life and breath, and all things. 26He made from one blood every nation of men to dwell on all the surface of the earth, having determined appointed seasons, and the boundaries of their dwellings, 27that they should seek the Lord, if perhaps they might reach out for him and find him, though he is not far from each one of us. 28'For in him we live, and move, and have our being.' As some of your own poets have said, 'For we are also his offspring.' 29Being then the offspring of God, we ought not to think that the Divine Nature is like gold, or silver, or stone, engraved by art and design of man. 30The times of ignorance therefore God overlooked. But now he commands that all people everywhere should repent, 31because he has appointed a day in which he will judge the world in righteousness by the man whom he has ordained; of which he has given assurance to all men, in that he has raised him from the dead."

— Acts 17:22-31 (WEB)

Because Paul's God could not be named, according to the customs of his people, it is possible that Paul's Athenian listeners would have considered his God to be "the unknown god par excellence".[6] His listeners may also have understood the introduction of a new god by allusions to Aeschylus' The Eumenides; the irony would have been that just as the Eumenides were not new gods at all but the Furies in a new form, so was the Christian God not a new god but rather the god the Greeks already worshipped as the Unknown God.[7] His audience would also have recognized the quotes in verse 28 as coming from Epimenides and Aratus, respectively.

Archaeology

[edit]

There is an altar dedicated to the Unknown God found in 1820 on the Palatine Hill of Rome. It contains an inscription in Latin that says:

SEI·DEO·SEI·DEIVAE·SAC

G·SEXTIVS·C·F·CALVINVSPR

DE·SENATI·SENTENTIA

RESTITVIT

This could be translated into English as: "Whether sacred to god or to goddess, Gaius Sextius Calvinus, son of Gaius, praetor, restored this on a vote of the senate."[8]

The altar is currently exhibited in the Palatine Museum.[9]

In Ancient Egypt

[edit]The idea of an unknown god, however, seems to predate the Greeks. For in Ancient Egypt, Amun was an unknowable god, not only in the sense of his name being unknown, but also his identity or essence.

In Neoplatonism

[edit]For Plotinus, the first principle of reality is "the One", an utterly simple, ineffable, unknowable subsistence which is both the creative source of the Universe[10] and the teleological end of all existing things.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ van der Horst, Pieter Willem (1998). Hellenism, Judaism, Christianity: essays on their interaction. Vol. The Altar of the 'Unknown God' in Athens (Acts 17:23) and the Cults of 'Unknown Gods' in the Graeco-Roman World. Peeters Publishers. pp. 187–220. ISBN 9789042905788.

- ^ Pseudo-Lucian, Philopatris, 9.14

- ^ Philostratus, Vita Apollonii 6.3

- ^ Pausanias' Description of Greece in 6 vols, Loeb Classic Library, Vol I, Book I.1.4

- ^ Plutarch's Lives

- ^ Tomson, Peter J.; Lambers-Petry, Doris (2003). The image of the Judaeo-Christians in ancient Jewish and Christian literature. Mohr Siebeck. p. 235. ISBN 3-16-148094-5.

- ^ Kauppi, Lynn Allan (2006). "Acts 17.16-34 and Aeschylus' Eumenides". Foreign but familiar gods: Greco-Romans read religion in Acts. Continuum International Publishing Group. pp. 83–93. ISBN 0-567-08097-8.

- ^ Dillon, Matthew; Garland, Lynda (2013). Ancient Rome: A Sourcebook. Routledge. p. 132.

- ^ Lanciani, Rodolfo (1892). Pagan and Christian Rome. Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company.

- ^ Brenk, Frederick (January 2016). "Pagan Monotheism and Pagan Cult". "Theism" and Related Categories in the Study of Ancient Religions. SCS/AIA Annual Meeting. Vol. 75. Philadelphia: Society for Classical Studies (University of Pennsylvania). Archived from the original on 6 May 2017. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

Historical authors generally refer to "the divine" (to theion) or "the supernatural" (to daimonion) rather than simply "God." [...] The Stoics, believed in a God identifiable with the logos or hegemonikon (reason or leading principle) of the universe and downgraded the traditional gods, who even disappear during the conflagration (ekpyrosis). Yet, the Stoics apparently did not practice a cult to this God. Middle and Later Platonists, who spoke of a supreme God, in philosophical discourse, generally speak of this God, not the gods, as responsible for the creation and providence of the universe. They, too, however, do not seem to have directly practiced a religious cult to their God.

External links

[edit]- "Vedic Hymn To the Unknown God". Translated by Max Mueller