Ukraine on Fire (film)

| Ukraine on Fire | |

|---|---|

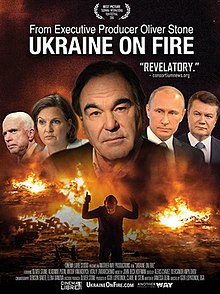

Film poster | |

| Directed by | Igor Lopatonok |

| Written by | Vanessa Dean |

| Produced by | Igor Lopatonok |

| Starring | |

| Narrated by | Lex Lang |

Production company | Another Way Productions |

| Distributed by | Another Way Productions Cinema Libre Studio |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 95 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

Ukraine on Fire is a film directed by Igor Lopatonok and premiered at the 2016 Taormina Film Fest.[1] It features Oliver Stone, the executive producer,[2] interviewing pro-Russian figures surrounding the Revolution of Dignity such as Viktor Yanukovich and Vladimir Putin.[3] The film portrays the events that led to the flight of Yanukovych in February 2014 as a coup d'état orchestrated by the United States with the help of far-right Ukrainian factions. The film's central thesis is that the U.S. had used Ukraine as a proxy against Russia for many years. It also claims that a large and influential section of Ukrainian protestors involved in the 2014 Revolution of Dignity were neo-Nazis.[4][5][6][7][8]

The film was regarded by critics as presenting a "Kremlin-friendly version of the events".[9] It was also criticized for advancing the Russian narrative about the revolution.[10]

Synopsis

[edit]The film starts by recounting historical themes such as the Cossack Hetmanate, World War I and the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, the annexation of Western Ukraine by the USSR, the Great Patriotic War, Ukrainian collaborationism in World War II, the massacre of Jews at Babyn Yar, the Volyn massacre of Poles and the guerilla war of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army against the Soviets up to the mid 1950s.

The film says that during the Cold War, the CIA maintained contact with Ukrainian nationalists in order to have possible channels for counterintelligence towards the USSR, mentioning Ukrainian nationalist leaders including Mykola Lebed, Stepan Bandera, Dmytro Dontsov, Andriy Melnyk and Roman Shukhevych.

It then maintains that the free market economy which was introduced after the collapse of the Soviet Union in the "crazy 1990s", gave rise to a small class of oligarchs who acquired vast wealth and power, while leaving the majority of the population in poverty.

A big part of the film is dedicated to far-right politics in Ukraine, including the organizations Svoboda, Tryzub and Right Sector.

The film mentions the Orange Revolution in which Ukrainians rejected a fraudulent presidential election, and then portrays some aspects of the Maidan protests, including the negotiations over a trade agreement with the European Union, the role of NGOs, and the appearance of US politicians such as Chris Murphy and John McCain. The film states that the Maidan protests, initially peaceful, began to escalate with the involvement of radical elements,[clarification needed] including Right Sector activists who were purportedly brought to the Maidan[by whom?] to "muscle" the peaceful demonstrations.

After that, the film presents Oliver Stone's interviews with Viktor Yanukovych and Vladimir Putin, in which they expound their view of the situation in 2013 regarding the trade agreement and why negotiations were paused. The film also covers selected aspects of the events leading to Yanukovych's removal from office by the Verkhovna Rada, Ukraine's parliament, claiming that the impeachment against him was unconstitutional.

Finally, the film presents events of the following months, including the invasion and annexation of Crimea by Russia, the war in eastern Ukraine, and the downing of the airliner MH17 by a Russian missile. The film criticizes NATO's eastward expansion and the imposition of sanctions against Russia. It questions the legitimacy of the post-Yanukovych government in Kyiv.

The film concludes by presenting the concept of the Doomsday Clock, which indicated a high level of global risk in 2015 due to the modernization of nuclear arsenals.

Release

[edit]The film premiered at the Taormina Film Festival in Italy on 16 June 2016;[11] thereafter, it did not receive a general theatrical release but was published as DVD on 18 July 2017.[12] Later, the documentary became also available in the video on demand market via Apple TV and Amazon Prime and since June 2021 also on YouTube. [9] It was aired in Russia on national television network REN TV in November 2016.

In March 2022, it was reported that the film had been removed from YouTube and Vimeo. YouTube explained they "removed this video for violating our violent or graphic content policy, which prohibits content containing footage of corpses with massive injuries, such as severed limbs"; subsequently, the film was uploaded to Rumble for free viewing.[13] As of 12 March 2022, the film was again available on YouTube, this time with a content warning attached.

Reception

[edit]The film was regarded as presenting "a Kremlin-friendly version of the events".[9][14] According to the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, "“Ukraine on Fire was derided for advancing the Russian narrative about Ukraine’s 2014 Euromaidan revolution, portraying it as a nationalist coup orchestrated by the United States".[10] Film narrates the misconception that "Ukraine has never been a united country".[15]

Andrew Roth, writing from Moscow for The Guardian, said that Ukraine on Fire is part of "a series of documentary projects featuring Stone about Russia and Ukraine that reflect a strongly pro-Kremlin worldview", remarking further that "Stone has noted that the films, which are strongly critical of the 2014 Maidan revolution and have been attacked as propaganda vehicles, are very popular in Russia."[16]

Stephen Velychenko, the University of Toronto's Chair of Ukrainian Studies, strongly criticized Stone's pro-Russian bias. While Velychenko accepts the possible involvement of the CIA, he allocates only a minor role to it compared to domestic political forces and argues that the film's focus on external forces only will lead to apologetics or conspiracy theories.[17]

Writing in Collectible Dry, Antonio Armano criticized that the film does not mention either Stalin's dekulakization or the Holodomor, a man-made famine organized by the Soviet regime, events which he argues may explain why the Nazi occupation during World War II was seen by some Ukrainians as welcomed liberation. Comparing Ukraine on Fire with the documentary Winter on Fire released one year earlier (and portrayed the 2014 revolution positively), he stated that Ukraine on Fire is a "less narrative and emotional" journalistic product. According to Armano, the film's main message is to avoid a new Cold War between the United States and Russia with the potential for nuclear confrontation.[18]

James Kirchick of The Daily Beast called the film a "dictator suckup",[7] noting that "Yanukovych ceased being president on 22 February 2014 because he fled Kiev, rendering himself incapable of performing his presidential duties under the Ukrainian constitution. Over three-quarters of the country’s parliament, including many members of Yanukovych’s own party, voted effectively to impeach him that day", and "It is astoundingly patronizing for Stone to lecture Ukrainians—thousands of whom have fought and died defending their dismembered country from an all-out invasion by their much more powerful neighbor—about what they do and do not know about Viktor Yanukovych, Russia and the potential for a new Cold War".

Rod Dreher, a writer for the American Conservative, said: "I expected 'Ukraine On Fire' to be propaganda, and indeed it was. But that doesn't mean it is entirely a lie, and in any case, it's important to know how the other side regards a conflict, if only to understand how they are likely thinking."[19]

Pavel Shekhtman, a Russian dissident persecuted by Russian authorities for alleged extremism, writing for the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group, also called the documentary "undistilled Kremlin propaganda", arguing that, of the main Ukrainian political figures described as neo-Nazis by Stone, only Oleh Tyahnybok resorted to xenophobia and antisemitic rhetoric.[20]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Giannavola, Salvatore (2016-06-17). "Taormina Film Fest: Oliver Stone e Igor Lopatonok presentano Ukraine on Fire". Telefilm Central (in Italian). Retrieved 2022-03-05.

Sono queste le keywords del docufilm di Igor Lopatonok e Oliver Stone che nella mattinata di ieri hanno presentato in anteprima nazionale 'Ukraine on Fire'.

- ^ "Oliver Stone: Reports Russia to blame for Ukraine violence are fake news". BelfastTelegraph.co.uk. 4 February 2017. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- ^ Sanders, Lewis (22 November 2016). "Putin's celebrity circle". dw.com. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- ^ M, J (2016-06-30). "Oliver Stone zoekt de waarheid achter Oekraïnecrisis in nieuwe documentaire" [Oliver Stone seeks truth behind Ukraine crisis in new documentary]. Knack Focus (in Dutch). Roularta Media Group. Retrieved 2022-03-05.

On his Facebook page, Oliver Stone stated at the end of 2014 that Yanukovytsh's resignation was actually a coup, directed by the CIA and therefore the United States. According to Stone, the Western press is withholding the facts that prove American involvement.

- ^ Peck Thompson, Christine (2018-06-22). "UKRAINE ON FIRE – Documentary Dives Deep Into Current Conflict Between Russian and Ukraine, Shows Another Side To The Story". AMFM Magazine. Retrieved 2022-03-05.

In addition to Putin, Stone interviews former President Viktor Yanukovych and Minister of Internal Affairs, Vitaliy Zakharchenko, who explain how the U.S. Ambassador and factions in Washington actively plotted for regime change.

- ^ Pavel Shekhtman (2016-12-05). "Oliver Stone's "Ukraine on Fire" is undistilled Kremlin propaganda". Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group. Retrieved 2022-06-07.

Oleh Tyahynbok is the only one of the three who has actually resorted to xenophobia and anti-Semitic rhetoric. But after the Maidan revolution he lost most of the seats in parliament that his party had, including his own.

- ^ a b Kirchick, James (January 5, 2015). "Oliver Stone's Latest Dictator Suckup". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on January 5, 2015. Retrieved January 5, 2015.

- ^ Armano, Antonio (2016-10-26). "Oliver Stone's Ukraine". Collectible DRY. Collectible Media Ltd. Retrieved 2022-06-13.

But this reconstruction lacks something, and that lack penalizes our understanding. We see no mention of Golodomor, the genocidal famine Stalin imposed on the country in the 1930s, killing millions of Ukrainians. There's no mention of Stalin's collectivization of lands, nor his persecution of religion. These oversights make it hard to understand why the Nazis were welcomed as liberators. They weren't welcomed because the Ukrainians were Nazis too, but because the population was desperate for salvation.

- ^ a b c Kozlov, Vladimir (23 November 2016). "Oliver Stone-Produced Ukraine Doc Causes Stir in Russia, TV Network Ramps up Security Amid Threats". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- ^ a b (Vlast.kz), Vyacheslav Abramov; (OCCRP), Ilya Lozovsky (10 October 2022). "Oliver Stone Documentary About Kazakhstan's Former Leader Nazarbayev Was Funded by a Nazarbayev Foundation". OCCRP. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- ^ Giannavola, Salvatore (2016-06-17). "Oliver Stone-produced 'Ukraine On Fire' premieres at film festival in Italy". Telefilm Central. Retrieved 2022-03-10.

As Oliver Stone admits, the project aims to inform a Western world very often trapped by biased and distorted information flows from media.

- ^ Ukraine on Fire - Release Dates at IMDb

- ^ Goldsberry, Jenny (2022-03-09). "YouTube flags Oliver Stone's Ukraine documentary". Washington Examiner. Retrieved 2022-03-12.

Reporter Sharyl Attkisson claimed that according to "recent experience," censorship will only serve to "[elevate] its importance and relevance."

- ^ Glas, Othmara (2022-08-19). "Für den Kreml? Streit um Oliver Stones Ukraine-Film in Leipzig" [For the Kremlin ? Dispute over Oliver Stone's Ukraine film in Leipzig]. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. Retrieved 2022-10-06.

Damit bedient er ein klassisches Propaganda-Narrativ des Kremls

[In doing so, he is using a classic Kremlin propaganda narrative] - ^ Mirra, Carl (2022-12-12). "Not One Inch, Unless It Is from Lisbon to Vladivostok: NATO-Russia Mythmaking and a Reimagined Kyivan Rus". Journal of Applied History. 4 (1–2): 126–148. doi:10.1163/25895893-bja10026. ISSN 2589-5893.

- ^ Roth, Andrew (2021-07-11). "Oliver Stone derided for film about 'modest' former Kazakh president". The Guardian. Retrieved 2022-06-13.

- ^ Velychenko, Stephen (January 1, 2015). "Stephen Velychenko: An open letter to Oliver Stone". Krytyka. Archived from the original on April 10, 2018. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

Do you really believe Mr. Stone that in any of the great events in world history during the past centuries the intelligence services and spies of the great powers of the time were not involved? Simply noting this fact in isolation from all other events leads either to apologetics or conspiracy theories.

- ^ Armano, Antonio (2016-10-26). "Oliver Stone's Ukraine". Collectible DRY. Collectible Media Ltd. Retrieved 2022-06-13.

But this reconstruction lacks something, and that lack penalizes our understanding. We see no mention of Golodomor, the genocidal famine Stalin imposed on the country in the 1930s, killing millions of Ukrainians. There's no mention of Stalin's collectivization of lands, nor his persecution of religion. These oversights make it hard to understand why the Nazis were welcomed as liberators. They weren't welcomed because the Ukrainians were Nazis too, but because the population was desperate for salvation.

- ^ Dreher, Rod (2022-03-14). "War on Our Own Memory". Retrieved 2022-06-13.

Because YouTube removed Oliver Stone's documentary "Ukraine On Fire," which tells the story of the 2014 Euromaidan protests from a Russian point of view, I watched it last night on Rumble. A few years ago, I had tried to watch Stone's 2017 interviews with Putin, broadcast on Showtime, but turned them off because it was obvious that Stone was enamored of his subject, and was not interested in asking hard questions. I expected "Ukraine On Fire" to be propaganda, and indeed it was. But that doesn't mean it is entirely a lie, and in any case, it's important to know how the other side regards a conflict, if only to understand how they are likely thinking.

- ^ Pavel Shekhtman (2016-12-05). "Oliver Stone's "Ukraine on Fire" is undistilled Kremlin propaganda". Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group. Retrieved 2022-06-07.

Oleh Tyahynbok is the only one of the three who has actually resorted to xenophobia and anti-Semitic rhetoric. But after the Maidan revolution he lost most of the seats in parliament that his party had, including his own.