Fort Huachuca

| Fort Huachuca | |

|---|---|

| Cochise County, Arizona Near Sierra Vista, Arizona in United States | |

| |

Insignia of units stationed at Fort Huachuca Motto: "From sabres to satellites" | |

Interactive map outlining Fort Huachuca | |

| Coordinates | 31°33′19″N 110°20′59″W / 31.555357°N 110.349754°W |

| Type | Army Post |

| Site information | |

| Owner | United States |

| Controlled by | |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Condition | Active |

| Website | Official Website |

| Site history | |

| Built | 3 March 1877 |

| In use | 143 years |

| Battles/wars | Apache Wars 1849–1924 Pancho Villa Expedition 1916–1917 |

| Garrison information | |

| Current commander | |

| Past commanders | List of Past Commanders

|

| Garrison | USAG Fort Huachuca |

| Occupants |

|

| Designations | National Register of Historic Places |

Fort Huachuca | |

Historic Commanding Officer's quarters | |

| Nearest city | Sierra Vista, Arizona |

| Area | 76,000 acres (310 km2) |

| Built | 1877 |

| Architect | US Army |

| NRHP reference No. | 74000443 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | 20 November 1974[3] |

| Designated NHLD | 11 May 1976[4] |

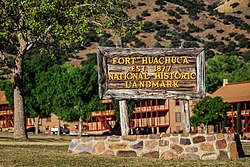

Fort Huachuca is a United States Army installation, established on 3 March 1877 as Camp Huachuca. The garrison is under the command of the United States Army Installation Management Command. It is in Cochise County in southeast Arizona, approximately 15 miles (24 km) north of the border with Mexico and at the northern end of the Huachuca Mountains, adjacent to the town of Sierra Vista. From 1913 to 1933, the fort was the base for the "Buffalo Soldiers" of the 10th Cavalry Regiment. During the build-up of World War II, the fort had quarters for more than 25,000 male soldiers and hundreds of WACs. In the 2010 census, Fort Huachuca had a population of about 6,500 active duty soldiers, 7,400 military family members, and 5,000 civilian employees. Fort Huachuca has over 18,000 people on post during weekday work hours.

The major tenant units are the United States Army Network Enterprise Technology Command (NETCOM) and the United States Army Intelligence Center. Libby Army Airfield is on post and shares its runway with Sierra Vista Municipal Airport. It was an alternate but never used landing location for the Space Shuttle. Fort Huachuca is the headquarters of Army Military Auxiliary Radio System. Other units include the Joint Interoperability Test Command, the Information Systems Engineering Command, the Electronic Proving Ground (USAEPG), and the Intelligence and Electronic Warfare Directorate.[5]

The fort has a radar-equipped aerostat (Tethered Aerostat Radar System), one of a series maintained for the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) by Harris Corporation. The aerostat is northeast of Garden Canyon and supports the DEA drug interdiction mission by detecting low-flying aircraft attempting to enter the United States from Mexico. Fort Huachuca contains the Western Division of the Advanced Airlift Tactics Training Center which is based at the 139th Airlift Wing, Rosecrans Air National Guard Base in Saint Joseph, Missouri.

History

[edit]The installation was founded to counter the Chiricahua Apache threat and secure the border with Mexico during the Apache Wars. On 3 March 1877, Captain Samuel Marmaduke Whitside led two companies of the 6th Cavalry and chose a site at the base of the Huachuca Mountains that provided sheltering hills and a perennial stream.[6][7] In 1882, Camp Huachuca was redesignated a fort.

General Nelson A. Miles commanded Fort Huachuca as his headquarters in his campaign against Geronimo in 1886. After the surrender of Geronimo in 1886, the Apache threat was extinguished, but the army continued to operate Fort Huachuca because of its strategic border position. In 1913, the fort became the base for the "Buffalo Soldiers", the 10th Cavalry Regiment composed of African Americans. It served this purpose for twenty years. During General Pershing's failed Punitive Expedition of 1916–1917, he used the fort as a forward logistics and supply base. From 1916 to 1917, the base was commanded by Charles Young, the first African American to be promoted to colonel. He left for medical reasons. In 1933, the 25th Infantry Regiment replaced the 10th Cavalry at the fort.

With the build-up during World War II, the fort had an area of 71,253 acres (288.35 km2), with quarters for 1,251 officers and 24,437 enlisted soldiers.[8] The 92nd and 93rd Infantry Divisions, composed of African-American troops, trained at Huachuca.

In 1947, the post was closed and turned over to the Arizona Game and Fish Department. However, at the outbreak of the Korean War, a January 1951 letter from the Secretary of the Air Force to the Governor of Arizona invoked the reversion clause of a 1949 deed. On 1 February 1951 the U.S. Air Force took official possession of Fort Huachuca, making it one of the few army installations to have had an existence as an air base.[9] The army retook possession of the base a month later and reopened the post in May 1951 to train engineers in airfield construction as part of the Korean War build up. The engineers built today's Libby Army Airfield. On 1 May 1953, after the Korean War, the post was again placed on inactive status with only a caretaker detachment.

On 1 February 1954, Huachuca was reactivated after a seven-month shut-down following the Korean War. It was the beginning of a new era for this one-time cavalry outpost, which saw Huachuca focused on electronic warfare. The army's Electronic Proving Ground opened in 1954, followed by the Army Security Agency Test and Evaluation Center in 1960, the Combat Surveillance and Target Acquisition Training Command in 1964, and the Electronic Warfare School in 1966. Also in 1966 the U.S. Army established the 1st Combat Support Training Brigade, whose mission was to train soldiers in the specialties of field wire and communication, telegraph communications (O5B wired and wireless)[clarification needed], light tactical vehicle driving, wheeled vehicle maintenance, and food service and administration due to the expanding need for these skills in Vietnam.

In 1967, Fort Huachuca became the headquarters of the U.S. Army Strategic Communications Command, which became the U.S. Army Communications Command in 1973, and U.S. Army Information Systems Command in 1984. It is now known as NETCOM after the army dropped the 9th Signal Command (Army) designation on 1 October 2011. NETCOM was realigned in 2014 as a subordinate command to United States Army Cyber Command from a direct reporting unit to the Headquarters, Department of the Army CIO/G6.[10]

Fort Huachuca was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1976 for its role in ending the Apache Wars, the last major military actions against Native Americans, and as the site of the Buffalo Soldiers.[4][11][12] Fort Huachuca maintains a cemetery known as the Fort Huachuca Post Cemetery.[13] Some 3,800 veterans and family members are buried there.

In 1980, the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment (SOAR) conducted aircraft training exercises from Fort Huachuca in preparation for Operation Honey Badger. This operation aimed to rescue captive American personnel in Iran. It was developed in the wake of Operation Eagle Claw's failure. The environment near the fort enabled 160th SOAR pilots to train and simulate flying in the mountainous desert terrain of Iran.

The fort was the site of the 2007 Conseil International du Sport Militaire.

Museums

[edit]Fort Huachuca has two museums in three buildings on post. The Ft. Huachuca Museum[14] occupies two buildings on Old Post, its main museum and gift shop (Building 41401), and a nearby spillover gallery called the Museum Annex (building 41305). It tells the story of Fort Huachuca and the U.S. Army in the American Southwest, with special emphasis on the Buffalo Soldiers and the Apache War. The Annex across the street (Old Post Theater) has outdoor displays, walkways, sitting areas, and historical statues.

The second museum is The U.S. Army Intelligence Museum, in the military intelligence (MI) Library on the MI school campus (Hatfield Street – Building 62723). The museum has a collection of historical artifacts including agent radio communication gear, aerial cameras, cryptographic equipment, an Enigma Code machine, two small drones and a section of the Berlin Wall. The museum's emphasis is on U.S. Army military intelligence history and includes displays of the organizational development of army intelligence. There is a small military intelligence gift shop with customized Fort Huachuca souvenirs.

All visitors, military or civilian, are welcome at the Ft. Huachuca Museum free of charge. Civilian visitors without a DoD ID card must pass a criminal background check before being allowed to pass the gate.[15] Foreign visitors must be escorted by active duty or retired military personnel.

Signal Commands

[edit]Fort Huachuca has a rich tradition in Army Signal and is currently home to NETCOM whose mission is to plan, engineer, install, integrate, protect, defend and operate army cyberspace, enabling mission command through all phases of operations. It used to be home to the 11th Signal Brigade. The 11th Signal Brigade has the mission of rapidly deploying worldwide to provide and protect command, control, communications, and computer support for commanders. They were deployed to provide signal operations during the 2003 invasion of Iraq. On 7 June 2013, the unit moved to Fort Hood, Texas. The Army Electronic Proving Ground (USAEPG), a forerunner in the research and development of defense technology, was conducted at Ft. Huachuca for several decades. The software-defined radios, Wideband Networking Waveform, and the Soldier Radio Waveform, were tested at USAEPG in 2014 for a network integration evaluation, NIE 15.2, at Fort Bliss, in 2015.[16]

Military Intelligence

[edit]In addition to the US Army Intelligence Center, Fort Huachuca is the home of the 111th Military Intelligence Brigade, which conducts MI training for the armed services. The Military Intelligence Officer Basic Leadership Course, Military Intelligence Captain's Career Course, and the Warrant Officer Basic and Advanced Courses are taught on the installation. The Army's MI branch also held the responsibility for unmanned aerial vehicles until April 2006. The program was reassigned to the Aviation branch's 1st Battalion, 210th Aviation Regiment, now 2nd Battalion, 13th Aviation Regiment. Additional training in Human Intelligence (e.g., interrogation, counterintelligence), Imagery Intelligence, and Electronic Intelligence and analysis is also conducted by the 111th. The 111th MI Brigade hosts the Joint Intelligence Combat Training Center at Fort Huachuca.

Education

[edit]Fort Huachuca Accommodation Schools is the school district for dependent children living on the base.[17] The schools are: Colonel Johnston Elementary School (K–2), General Myer Elementary School (3–5), and Colonel Smith Middle School (6–8).[18] The zoned high school is Buena High School, operated by the Sierra Vista Unified School District, in Sierra Vista.[19]

Notable people

[edit]People who have served or lived at Fort Huachuca:

- Brigadier General Samuel Whitside, founded Camp Huachuca.

- Major General Leonard Wood, Medal of Honor recipient and Chief of Staff of the Army from 1910 to 1914 (after whom Fort Leonard Wood in Missouri is named).

- Colonel Cornelius C. Smith, Medal of Honor recipient and head of the Philippine Constabulary from 1910 to 1912. He accepted surrender of Mexican Colonel Emilio Kosterlitzky while stationed at Huachuca in 1913 and was later Huachuca commandant from 1918 to 1919.

- Bullet Rogan (Negro league baseball) 25th Infantry Regiment

- Cornelius C. Smith Jr., historian of Arizona, California, and the Southwestern United States.

- John Henry, played professional baseball for the Washington Senators and Boston Braves from 1910 to 1918.

- Colonel Sidney Mashbir, Commandant of Allied Translator and Interpreter Section, Military Intelligence Service during World War II.

- General Alexander Patch, decorated officer who commanded Army and Marine forces in the Guadalcanal campaign and later the 7th Army in Europe during World War II.

- General James Gavin (82nd Airborne Division)

- General Robert Sink (101st Airborne Division)

- Lieutenant General Sidney T. Weinstein, one of the driving forces behind reorganizing Army intelligence in late 1970s and 1980s.

- Captain Amadou Sanogo, junta leader in the West African country of Mali, completed intelligence training at Fort Huachuca in 2008.

- Specialist 5 Bobby Murcer, Major League Baseball player, New York Yankees, 1967–1969. 1st Training Brigade.

- Luis Robles, goalkeeper for the New York Red Bulls of Major League Soccer, was born at Fort Huachuca in 1984.

- Jayne Cortez, poet, born at Fort Huachuca in 1934.

- Lieutenant General Robert P. Ashley Jr., served as the Commanding General of the Army Intelligence Center of Excellence and Fort Huachuca from April 2013 to July 2015.[20]

- Lieutenant General Scott D. Berrier, served as the Commanding General of the Army Intelligence Center of Excellence and Fort Huachuca from July 2015 to July 2017.[21]

In popular culture

[edit]- Captain Newman, MD (1963), starring Gregory Peck as the title character, was filmed at Fort Huachuca.

- The opening sequence of Suppose They Gave a War and Nobody Came (1969) was filmed at Ft. Huachuca. This movie was supported by the 1st Training Brigade. It stars Brian Keith and Tony Curtis.

- In Scent of a Woman (1992) starring Al Pacino as Lt. Colonel Frank Slade, Slade tells his companion Charlie Simms that he dreamed of The Oak Room's rolls when he was at Fort Huachuca. "Bread's no good west of the Colorado. Water's too alkaline."

Climate

[edit]| Climate data for Fort Huachuca, Arizona | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 81 (27) |

84 (29) |

88 (31) |

96 (36) |

104 (40) |

104 (40) |

105 (41) |

101 (38) |

102 (39) |

99 (37) |

89 (32) |

81 (27) |

105 (41) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 58.8 (14.9) |

61.6 (16.4) |

67.3 (19.6) |

74.1 (23.4) |

81.5 (27.5) |

90.9 (32.7) |

89.3 (31.8) |

87.3 (30.7) |

84.6 (29.2) |

77.3 (25.2) |

67.0 (19.4) |

59.4 (15.2) |

74.9 (23.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 33.8 (1.0) |

35.9 (2.2) |

40.8 (4.9) |

46.1 (7.8) |

53.6 (12.0) |

63.0 (17.2) |

65.3 (18.5) |

63.5 (17.5) |

59.7 (15.4) |

51.0 (10.6) |

40.1 (4.5) |

34.6 (1.4) |

49.0 (9.4) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 1 (−17) |

4 (−16) |

18 (−8) |

23 (−5) |

32 (0) |

38 (3) |

44 (7) |

46 (8) |

35 (2) |

24 (−4) |

10 (−12) |

6 (−14) |

1 (−17) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.08 (27) |

0.94 (24) |

0.77 (20) |

0.27 (6.9) |

0.23 (5.8) |

0.50 (13) |

3.83 (97) |

3.44 (87) |

1.73 (44) |

0.86 (22) |

0.74 (19) |

1.09 (28) |

15.47 (393) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 1.2 (3.0) |

2.0 (5.1) |

1.1 (2.8) |

0.2 (0.51) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.5 (1.3) |

1.9 (4.8) |

6.9 (18) |

| Source: http://www.wrcc.dri.edu/cgi-bin/cliMAIN.pl?az3120. | |||||||||||||

Gallery

[edit]-

Fort Huachuca in 1918

-

Private William Major and Private Andrew Paxson on patrol of Fort Huachuca in 1942.

-

Aerial photograph of Fort Huachuca from the 1950s

-

Private Anthony Devlin operating a PPS-4 Radar System in 1956.

-

Fort Huachuca in 1970s

-

Aerial View of Fort Huachuca in the 1970s

-

USAF Security Forces on a training exercise at Fort Huachuca.

-

American Boyd Melson (right), during the 2007 Military World Games, at which he won a gold medal at Fort Huachuca

-

The Huachuca Mountains are the backdrop of several ranges on Fort Huachuca.

-

Fort Huachuca Old Post

-

Huachuca Mountains

-

Overlooking Fort Huachuca from Reservoir Hill

-

Overlooking Fort Huachuca (Old Post) from Reservoir Hill

References

[edit]- ^ "Invitation Letter from BG Hiestand to LTG Walters" (PDF). cia.gov/library. Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 January 2017. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ^ "Photograph/color portrait of BG Stubblebine". azmemory.azlibrary.gov. Arizona Memory Project. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. 23 January 2007.

- ^ a b "Fort Huachuca". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2 February 2015. Retrieved 27 September 2007.

- ^ "Fort Huachuca Units/Tenants". home.army.mil/huachuca/. United States Army. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ^ Russell, Major Samuel L., "Selfless Service: The Cavalry Career of Brigadier General Samuel M. Whitside from 1858 to 1902." MMAS Thesis, Fort Leavenworth: U.S. Command and General Staff College, 2002.

- ^ "History of Fort Huachuca". home.army.mil/huachuca. United States Army. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ^ Stanton, Shelby L. (1984). Order of Battle: U.S. Army World War II. Novato, California: Presidio Press. p. 600. ISBN 089141195X.

- ^ "Fort Huachuca Army Base in Cochise, Arizona | MilitaryBases.com". militarybases.com. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- ^ "Fort Huachuca – General History", U.S. Army Intelligence Center and Fort Huachuca, Accessed 2 March 2018

- ^ George R. Adams (January 1976). ""Fort Huachuca", National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination". National Park Service.

- ^ "Fort Huachuca –Accompanying photos, 12 from 1976, 4 from c. 1890, 5 from 1975; National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination". National Park Service. January 1976.

- ^ Sierra Vista, Arizona : history : more than what you learned in school. Sierra Vista: City of Sierra Vista : Sierra Vista Visitor Center, Sierra Vista. 2012. OCLC 1222862119.

- ^ "Fort Huachuca Museum and Annex – U.S. Army Center of Military History".

- ^ "The United States Army | Fort Huachuca, AZ". Archived from the original on 11 August 2016. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- ^ Right frequency for radio testing: Teaming, innovation Retrieved 2015-05-28[full citation needed]

- ^ "2020 Census – School District Reference Map: Cochise County, AZ" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 25 July 2022. – Text list

- ^ "Home". Fort Huachuca Accommodation Schools. Retrieved 25 July 2022.

- ^ "Fort Huachuca Education". Military One Source. Retrieved 25 July 2022. – this website has a .mil domain.

- ^ Vasey, Joan (6 August 2015). "New commander takes charge of Fort Huachuca during July 31 ceremony". United States Army. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- ^ "Search". AFCEA International.

Further reading

[edit]- Smith, Cornelius C. Jr. Fort Huachuca: The Story of a Frontier Post. Fort Huachuca, Arizona: 1978.[ISBN missing]

External links

[edit]- United States Army posts

- Military installations in Arizona

- 1877 establishments in Arizona Territory

- Buildings and structures in Cochise County, Arizona

- Forts in Arizona

- Military intelligence

- Lockheed Martin-associated military facilities

- National Historic Landmarks in Arizona

- Forts on the National Register of Historic Places in Arizona

- Sierra Vista, Arizona

- National Register of Historic Places in Cochise County, Arizona

- Military installations established in 1877