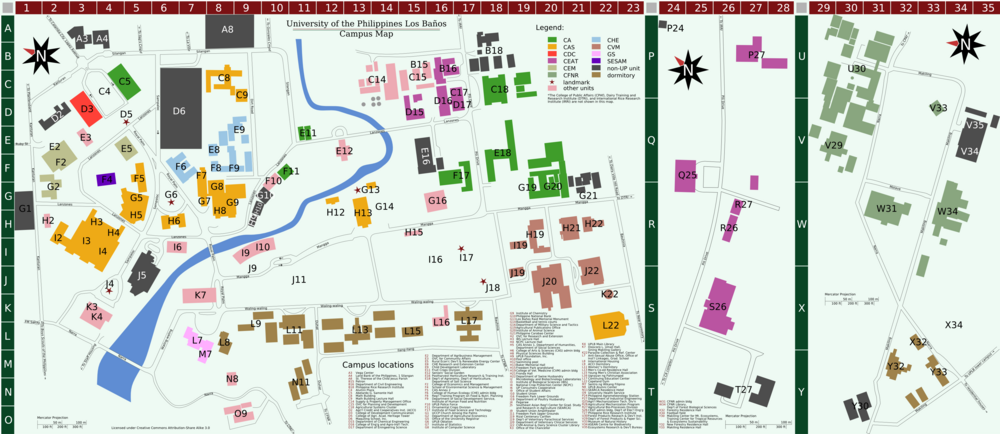

Campus of University of the Philippines Los Baños

The main campus of University of the Philippines Los Baños (UPLB) is located in the towns of Los Baños and Bay in the province of Laguna, 64 km (40 mi) southeast of Manila. The complex covers 5,445 ha (13,450 acres) of land encompassing the entire Makiling Forest Reserve (MFR) and surrounding areas. Its land grants in the provinces of Laguna, Negros Occidental, and Quezon have a combined area of 9,760 ha (24,100 acres).[2] The Total Campus Area (Rural) 15,205 hectares (37,570 acres).

The campus contains over 300 buildings.[3] Equipment and facilities are estimated to be worth ₱10.6 billion (US$245 million)[4] according to UPLB's financial statement for 2009.[needs update][5] The university manages eight student dormitories inside the campus, which housed 2,170 of the 11,980 students enrolled in 2008.[6][7]

As of 2007[update], UPLB's 12 libraries, collectively referred to as the University Library, hold a total of 346,061 volumes.[2] The University Library is a periodic recipient of publications from the United Nations agencies (namely the UNFAO, UN-HABITAT, and UNU) and the World Bank. It is a contributor to the International Information System for Agricultural Services and Technology, to which it contributed almost 30,000 titles between 1975 and 2010.[8][9]

History

[edit]The campus was established in 1909 on 72.63 ha (179.5 acres) of abandoned farmland at the foot of Mount Makiling, purchased by the University of the Philippines (UP) Board of Regents to serve as the campus of the newly created UP College of Agriculture (UPCA). Students helped clear the land, and the first classes were held in tents. Practical instruction was done at plantations on campus, such as those for corn, sugar cane and tobacco. Act 2730 of the Philippine Legislature in February 1918 authorized the appropriation of 379 ha (940 acres) for the creation of an agricultural experiment station. At the same time, funding of ₱125,000 (US$2,890)[4] was used by the college to acquire 261.76 ha (646.8 acres) for experimental farms and pasture.[10][11]

Most of the early structures were demolished during the Japanese occupation of the Philippines (1941–1945),[12] but some still exist, including the Palma Bridge and Baker Memorial Hall (both built during Dean Bienvenido M. Gonzalez's term from 1927 to 1938). All the student residences, 23 College of Agriculture buildings, 13 student dormitories and bungalows, and 22 faculty and employee houses were destroyed during the Second World War. The School of Forestry was also devastated. Only the agricultural engineering building was left undamaged.[1]

Grants from USAID and Mutual Security Agency in the 1950s accelerated the development of the campus. The Graduate School building, the UPCA Library (now College of Arts and Sciences building), and the Women's Dormitory (now the Math Building) were built as a result. Meanwhile, grants from the United States Economic Cooperation Agency (worth US$239,552), the International Cooperation Administration (ICA) (worth US$175,000), and ICA-National Economic Council allowed the construction of the Forest Products Laboratory (claimed by Centennial Panorama: Pictorial History of UPLB to be the "largest and best equipped in the eastern hemisphere" at the time it was constructed) in 1954,[13] the Agricultural Credit and Cooperatives Institute in 1957, and further construction of school and dormitory buildings in the School of Forestry campus in the 1960s.[1][14]

Aside from international assistance, five-year development programs during the terms of Dean Domingo Lantican (1958–1971) of the School of Forestry, and Dean Dioscoro Umali (1959–1970) of the College of Agriculture were also instrumental in developing the campus. During the implementation of these programs, the administration buildings of the College of Agriculture and the College of Development Communication as well as staff houses and roads were built.[14]

Since 2008 efforts have been put into renovation and beautification of existing structures to repair damage from Typhoon Xangsane in 2006 and to promote the campus as a "walking museum" and ecotourism center. Construction of an 11,000-seater convention center and cable cars connecting the lower and upper campuses have been proposed as part of the ecotourism plan.[15] Beautification projects include paving of pathways and construction of lampposts.[16] Some students criticized the program, arguing that the funds would have been better allocated for the renovation of classrooms, laboratories, and other academic facilities.[17]

A memorandum issued by Chancellor Luis Rey I. Velasco in 2010 instructed UPLB to conserve energy to reduce operating costs. The plan calls for reduced use of electric appliances (such as air conditioners, electric stoves and ovens), car pooling, and recycling.[18]

Areas

[edit]Upper campus

[edit]The College of Forestry and Natural Resources, College of Public Affairs, ASEAN Center for Biodiversity,[19] National Arts Center,[20] Philippine High School for the Arts,[21] the site of the National Jamboree of the Boy Scouts of the Philippines,[22] and the Center for Philippine Raptors[23] are in the upper campus. It includes the entire 4,347-hectare (10,740-acre)[24] Makiling Forest Reserve. It is also the site of the Bureau of Plant Industry-Makiling Botanic Gardens, one of the oldest parts of the campus. The gardens are located where the tents used as classrooms were set up during the first four months of the university's history.[11]

The MFR serves as an outdoor laboratory to students, primarily of the College of Forestry and Natural Resources. ₱5 million (US$156,000)[4] was designated for its conservation and development in 2011.[25] The MFR was created in 1910 under the Bureau of Forestry. Jurisdiction over MFR was transferred to UP in 1960. The National Power Corporation acquired complete jurisdiction of the MFR in 1987 as part of the Philippines' energy development program under President Corazon Aquino. The MFR was returned to UPLB three years later under the terms of Republic Act 6967.[26][27]

In 2008 Representative Del De Guzman of the 2nd district of Marikina filed HB 1143, which, if passed into law, would have transferred 57.77 ha (142.8 acres) of the MFR to the jurisdiction of the Boy Scouts of the Philippines.[28] The bill was strongly opposed by UPLB, citing possible mismanagement and deforestation of the site if placed under the BSP, among other reasons.[29][30][31][32] The bill has been pending in the House Committee on Natural Resources since August 2007.[33]

Lower campus

[edit]

The 1,098-hectare (2,710-acre)[2] lower campus, located at the foot of Mt. Makiling, is the location of most UPLB units and affiliated entities, including the International Rice Research Institute,[34] World Agroforestry Centre,[35] and the Southeast Asian Regional Center for Graduate Study and Research in Agriculture (SEARCA).[36]

The Molawin River, a tributary of Laguna de Bay, runs through the campus. Several bridges, such as the Palma Bridge (named after UP President Rafael V. Palma), cross the river. A 1996 UPLB study found high concentrations of nitrates and phosphates in the river, believed to be from decaying garbage and domestic waste.[37] There have been recent efforts to rehabilitate the river, such as planting Mussaenda and Hibiscus on its banks.[38][39]

Land grants

[edit]UPLB has three major land grants provided by the government of the Philippines: the Laguna-Quezon Land Grant, the La Carlota Land Grant, and the Laguna Land Grant.[2]

The 5,719-hectare (14,130-acre) Laguna-Quezon Land Grant, acquired in February 1930, is located in the towns of Real, Quezon, and Siniloan, Laguna. It covers some portions of the Sierra Madre mountain range, and hosts the university's Citronella and lemongrass plantations.[40][41] The 705-hectare (1,740-acre) La Carlota Land Grant is situated in Negros Occidental, a province in the Western Visayas region. Acquired in May 1964, it houses the PCARRD-DOST La Granja Agricultural Research Center,[42] which serves as a research center for various upland crops.[2][43] The 3,336-hectare (8,240-acre)[2] Laguna Land Grant, located in Paete, Laguna, is mostly undeveloped.[44]

Numerous parties have expressed interest in developing the land grants. Proposed projects include construction of dams and tree farms for Moringa oleifera, pineapples and rubber. UPLB has not entertained the potential investors due to the "lack of a solid development plan."[44]

Buildings and landmarks

[edit]

Many of the prominent buildings in the campus were designed by Leandro Locsin, a National Artist for Architecture who is known for his extensive use of concrete and simplistic designs.[45]

The Dioscoro L. Umali Hall, an auditorium named after Dean Dioscoro L. Umali, was built during Umali's US$6-million and ₱23-million (US$533,000)[4] Five-Year Development Program implemented in 1965.[14][46] Arkitekturang Filipino, a collaboration of the National Commission for Culture and the Arts and the United Architects of the Philippines, calls it a "clear example of his distinct architecture", and notes its resemblance to the Nicanor Abelardo Hall at the Cultural Center of the Philippines.[47] It houses the Sining Makiling art gallery.[23]

The Main Library, with a floor area of 6,336 m2 (68,200 sq ft) and a seating capacity of 510, is the largest library in UPLB. It holds 195,282 volumes, theses, and digital sources, and 1,215 serial titles.[2] It was originally built as the SEARCA library in 1974. It was eventually transferred to the university as the successor of the University of the Philippines College of Agriculture Library.[48][46] It is believed to be the largest agricultural library in Asia.[49]

The Rizal Memorial Centenary Carillon, built in 1996, is named after Philippine National Hero José Rizal. It has 37 bells ranging from F three octaves below middle C up to G above middle C,[50][51] making it the second largest non-traditional carillon in the Asia-Pacific region in terms of number of bells. It is one of only two non-traditional carillons in the Philippines.[52]

The Student Union Building houses the offices of the Office of Student Affairs, University Food Service,[53] University Student Council, and UPLB Perspective (the official student publication of UPLB).[54] The Student Union, along with the three aforementioned buildings, was designed by Locsin.[47]

A replica of the Oblation and the Philippine Pegasus (also referred to as the Pegaraw; a winged tamaraw) were sculpted by National Artist Napoleon Abueva.[23][55] The original Oblation is a 3.5-metre (11 ft) statue by Guillermo Tolentino, Abueva's mentor, commissioned in 1935 by UP President Rafael Palma. The sculpture is based on the second stanza of Rizal's Mi último adiós (Spanish for My last farewell). A replica of the Oblation can be found on each of the major UP campuses, and has become the campuses' identifying landmark.[56][57]

Transportation and amenities

[edit]Public utility jeepneys are a popular means of transportation around the campus. Jeepney drivers are required to post kanan (Tagalog for "right") or kaliwa (Tagalog for "left"), in reference to their direction. Since August 2007 a new jeepney route has been in force. The new route prohibits access to the middle campus—which contains most of the university's main buildings—to promote walking and to lessen noise and air pollution inside the campus. As this part of the campus was the destination of many passengers, jeepney drivers estimated the change would result in a loss of ₱200–300 (US$5–7)[4] and a 90 percent loss of passengers. Due to this, the implementation was met with protests, including a transport strike. A walkout was staged by around 500 students, citing the lack of community consultation before implementation of the plan.[58][59] The mayor of Los Baños refused to interfere.[60]

The campus is also served by the UP Los Baños railway station operated by Philippine National Railways, although currently no trains stop at the station.

Numerous congregations can be found near UPLB. These include the Catholic parishes of St. Therese of the Child Jesus[61] and San Antonio de Padua,[62] the UCCP Church Among the Palms,[63] and Victory Los Baños.[64] Other amenities include banks (including LBP,[65] Plantersbank,[66] and PNB)[67] and malls, such as Robinsons Town Mall Los Baños.[68] Security is provided by the University Police Force[69] and the Community Support Brigade[70] in addition to the police force of the local government. Medical services are provided by the University Health Service, a 30-bed hospital with specialized facilities, such as a diabetes clinic and a neonatal intensive-care unit, in addition to its emergency and operating rooms.[71] It is identified as a "Center of Quality" by PhilHealth.[72]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Fernando A. Bernardo (2007). "Chs. 6–8". Centennial Panorama: Pictorial History of UPLB. Los Baños, Laguna: University of the Philippines Los Baños Alumni Association, Inc. pp. 75–122. ISBN 978-971-547-252-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Facilities, Equipment and Library Resources". University of the Philippines Los Baños Office of the Vice-Chancellor for Research and Extension. Archived from the original on July 23, 2011. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ^ Rachel C. Barawid (April 15, 2009). "UPLB at 100: The country's pride". Manila Bulletin. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Approximate conversion value as of May 2011

- ^ University of the Philippines (December 31, 2009). Consolidated Annual Audit Report on the University of the Philippines. Commission on Audit. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ^ A Statement on the Large Class Size Project (PDF). University of the Philippines Los Baños. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 23, 2011. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- ^ JAA Oruga (June 9, 2009). "UPLB to build two new dorms". University of the Philippines Los Baños. Archived from the original on July 23, 2011. Retrieved April 29, 2011.

- ^ "Search AGRIS from 1975 to date". International Information System for Agricultural Services and Technology. Retrieved April 5, 2011.

- ^ "Brief History, Mission, and Vision". University of the Philippines Los Baños Main Library. March 11, 2009. Archived from the original on August 20, 2011. Retrieved 2011-04-06.

- ^ "Historical Background". University of the Philippines Los Baños. Archived from the original on August 23, 2011. Retrieved April 12, 2011.

- ^ a b Fernando A. Bernardo (2007). "Chs. 1–3". Centennial Panorama: Pictorial History of UPLB. Los Baños, Laguna: University of the Philippines Los Baños Alumni Association, Inc. pp. 3–46. ISBN 978-971-547-252-4.

- ^ "Japanese Occupation of the Philippines". Philippine History. Retrieved June 12, 2011.

- ^ "History". Forest Products Research and Development Institute. July 1, 2007. Retrieved April 13, 2011.

- ^ a b c d Fernando A. Bernardo (2007). "Chs. 9–10". Centennial Panorama: Pictorial History of UPLB. Los Baños, Laguna: University of the Philippines Los Baños Alumni Association, Inc. pp. 123–160. ISBN 978-971-547-252-4.

- ^ Celeste Ann Castillo Llaneta (March 2011). "Science meets Culture meets Nature: UPLB envisions Mariang Makiling Eco-Tourism Village". UP Newsletter. 32 (3). Quezon City: University of the Philippines. Archived from the original on March 20, 2012. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ Faith Allyson Buenacasa; et al. (January 29, 2009). "Admin steps up UPLB ecotourism projects". UPLB Perspective. 35 (7): 6. Retrieved April 15, 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Katrina Elauria (December 17, 2008). "UPLB admin steps up beautification campaign" (PDF). UPLB Perspective. 35 (5): 2. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ Office of the Chancellor (October 13, 2010). "CLRIV reminds constituents to conserve energy". University of the Philippines Los Baños. Archived from the original on June 24, 2011. Retrieved April 24, 2011.

- ^ "Contact Us". ASEAN Center for Biodiversity. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- ^ "National Arts Center". Cultural Center of the Philippines. Archived from the original on March 12, 2011. Retrieved April 16, 2011.

- ^ "Official website". Philippine High School of the Arts. Archived from the original on February 27, 2011. Retrieved April 16, 2011.

- ^ Niña Catherine Calleja (October 23, 2007). "17,000 boy scouts start Jamboree in Mt. Makiling". Manila Bulletin. Archived from the original on October 9, 2012. Retrieved April 16, 2011.

- ^ a b c "UP Los Baños". University of the Philippines Office of Alumni Relations. Archived from the original on December 21, 2010. Retrieved 2011-04-16.

- ^ "Facilities, Equipment and Library Resources". University of the Philippines Los Baños Office of the Vice-Chancellor for Research and Extension. Archived from the original on July 23, 2011. Retrieved April 16, 2011.

- ^ Congress of the Philippines (2011). "A.8. University of the Philippines System" (PDF). Republic Act No. 10147 (PDF). Department of Budget and Management. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 28, 2011. Retrieved May 22, 2011.

- ^ Congress of the Philippines (October 15, 1990). "Republic Act No. 6967". Arellano Law Foundation. Retrieved April 16, 2011.

- ^ "Makiling Forest Reserve (MFR)". Philippine Council for Agriculture, Forestry and Natural Resources Research and Development. Archived from the original on February 26, 2009. Retrieved April 16, 2011.

- ^ Del De Guzman (July 16, 2007). House Bill No. 1143 (PDF). Quezon City: House of Representatives of the Philippines. p. 3.

- ^ Ferdinand Castro (November 21, 2008). "Plans to put Mt. Makiling under Boy Scouts opposed". Manila Bulletin. Retrieved April 16, 2011.

- ^ Bernice P. Varona (November 1, 2008). "UPLB says no to House Bill 1143". UP Newsletter. 29 (11). Quezon City: University of the Philippines. Archived from the original on March 20, 2012. Retrieved April 16, 2011.

- ^ "UPLB says NO to House Bill 1143 and the fragmentation of the Mt. Makiling Forest Reserve". University of the Philippines Los Baños. November 10, 2008. Archived from the original on August 23, 2011. Retrieved April 16, 2011.

- ^ Nikko Angelo Oribiana (December 15, 2008). "BSP eyes control of Jamboree". UPLB Perspective. 35 (4): 3. Retrieved April 16, 2011.

- ^ "NO. HB01143". Congress of the Philippines. Archived from the original on October 8, 2012.

- ^ "Contact Us". International Rice Research Institute. Archived from the original on March 24, 2011. Retrieved 2011-03-27.

- ^ "Site Based Los Banos (Philippines)". World Agroforestry Centre. Archived from the original on September 10, 2018. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- ^ "Contact Us". Southeast Asian Regional Center for Graduate Study and Research in Agriculture. Archived from the original on December 13, 2010. Retrieved 2011-03-27.

- ^ Ma. Victoria O. Espaldon; et al. (2005). Rodel D. Lasco; Ma. Victoria O. Espaldon (eds.). Ecosystem and People: The Philippine Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA) Sub-global Assessment (PDF). University of the Philippines Los Baños College of Forestry and Natural Resources. p. 57. ISBN 971-547-237-0. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 27, 2011. Retrieved April 16, 2011.

- ^ "University teams up with senior citizens and drugstore to help restore Molawin Creek". University of the Philippines Los Baños. August 12, 2010. Archived from the original on December 21, 2012. Retrieved April 16, 2011.

- ^ "UPLB botanist wants science brought to Laguna Lake, riverside communities". Balita.ph. Philippine News Agency. November 6, 2010. Retrieved April 16, 2011.

- ^ "Citronella Essential Oil Production at the Laguna-Quezon Land Grant". University of the Philippines Los Baños Land Grant Management Office. September 9, 2010. Archived from the original on June 10, 2011. Retrieved 2011-03-27.

- ^ "History". University of the Philippines Los Baños Land Grant Management Office. Archived from the original on June 10, 2011. Retrieved 2010-10-18.

- ^ Rudy A. Fernandez (January 1, 2001). "Research consortium for ARMM pushed". The Philippine Star. Archived from the original on February 1, 2013. Retrieved March 27, 2011.

- ^ "Accomplishments". University of the Philippines Los Baños. Archived from the original on August 23, 2011. Retrieved 2011-03-27.

- ^ a b "Brief History". University of the Philippines Los Baños Land Grant Management Office. December 3, 2010. Archived from the original on June 10, 2011. Retrieved 2011-03-27.

- ^ "Leandro V. Locsin". National Commission for Culture and the Arts. Archived from the original on January 18, 2012. Retrieved April 16, 2011.

- ^ a b Fernando A. Bernardo (2007). "Chs. 11–12". Centennial Panorama: Pictorial History of UPLB. Los Baños, Laguna: University of the Philippines Los Baños Alumni Association, Inc. pp. 161–186. ISBN 978-971-547-252-4.

- ^ a b "Leandro V. Locsin". Arkitekturang Filipino. Retrieved March 27, 2011.

- ^ "Brief History, Mission, and Vision". University of the Philippines Los Baños Main Library. March 11, 2009. Archived from the original on August 20, 2011. Retrieved 2011-04-16.

- ^ Karen Lapitan (August 1, 2008). "How (not) to get lost in UPLB". UPLB Perspective. 35 (1). Retrieved April 21, 2011.

- ^ Kate Kirk; Katherine Lopez (2001). A guide to Los Baños for IRRI international staff & families. International Rice Research Institute. p. 16. ISBN 971-22-0160-0. Retrieved April 17, 2011.

- ^ "Rizal Centenary Carillon". Guild of Carilloneurs in North America. August 24, 2008. Archived from the original on June 25, 2011. Retrieved April 17, 2011.

- ^ "Non-traditional carillons in Asia and the Pacific Rim: index by size". Guild of Carilloneurs in North America. January 20, 2010. Archived from the original on June 25, 2011. Retrieved April 17, 2011.

- ^ "Basic Student Information". University of the Philippines Los Baños. Archived from the original on August 23, 2011. Retrieved 2011-04-18.

- ^ Karen Lapitan (August 1, 2008). "How (not) to get lost in UPLB". UPLB Perspective (in Tagalog). 35 (1). Retrieved April 21, 2011.

- ^ Jennielyn R. Carpio; JG Garcia (November 3, 2010). "Portals, landmarks turned over to UPLB; new marker unveiled". University of the Philippines Los Baños. Archived from the original on June 24, 2011. Retrieved April 21, 2011.

- ^ "U.P. Oblation History". University of the Philippines Alumni Association of Greater Chicago. Archived from the original on November 27, 2010. Retrieved April 21, 2011.

- ^ "Napoleon V. Abueva, the National Artist". Oblation.com.ph. Retrieved April 21, 2011.

- ^ University of the Philippines Los Baños University Student Council (February 26, 2009). "Drivers paralyze transport in UPLB; students support transport strike amid continuing protests for GMA ouster". Arkibong Bayan. Retrieved April 24, 2011.

- ^ Rogene Gonzales (September 27, 2007). "OVCCA rejects USC, LBCTF appeals: PUJ rerouting 'dry run' continues" (PDF). UPLB Perspective. 34 (1): 10. Retrieved April 24, 2011.

- ^ Angelica Mendoza; Harriet Melanie Zabala (October 22, 2007). "Velasco firm on ambulant vending, rerouting issues" (PDF). UPLB Perspective. 34 (2): 2. Retrieved April 24, 2011.

- ^ "Catholic Mass Schedule at St. Therese of the Child Jesus Parish". Philippine Catholic Mass Schedule. Retrieved April 9, 2011.

- ^ "Official website". San Antonio de Padua Parish, Los Baños, Laguna. Archived from the original on May 2, 2014. Retrieved April 9, 2011.

- ^ "Official website". UCCP Church Among the Palms. Archived from the original on February 25, 2011. Retrieved April 9, 2011.

- ^ "Victory Los Baños" (PDF). Victory Christian Fellowship. September 9, 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 16, 2009. Retrieved April 9, 2011.

- ^ "Branch locator". Land Bank of the Philippines. Archived from the original on May 26, 2011. Retrieved April 9, 2011.

- ^ "Branches". Planters Development Bank. Archived from the original on April 3, 2011. Retrieved April 9, 2011.

- ^ "Luzon Branches". Philippine National Bank. Retrieved April 9, 2011.

- ^ "Robinsons Town Mall Los Baños". Robinsons Malls. Archived from the original on April 15, 2011. Retrieved April 9, 2011.

- ^ "UPLB University Police Force". University of the Philippines Los Baños. September 15, 2010. Archived from the original on July 23, 2011. Retrieved April 9, 2011.

- ^ Eduardo A. Panaya. "Community Support Brigade". University of the Philippines Los Baños Office of the Vice-Chancellor for Community Affairs. Retrieved April 9, 2011.

- ^ "Facilities/Services/Programs". University of the Philippines Los Baños. Archived from the original on August 23, 2011. Retrieved April 25, 2011.

- ^ Ma. Joanna G. Viñas; Ma. Cristina W. Zafaralla (April 25, 2011). "PhilHealth accredits UHS as Center of Quality". University of the Philippines Los Baños. Archived from the original on December 21, 2012. Retrieved May 13, 2011.