UDA South Belfast Brigade

The UDA South Belfast Brigade is the section of the Ulster loyalist paramilitary group, the Ulster Defence Association (UDA), based in the southern quarter of Belfast, as well as in surrounding areas. Initially a battalion, the South Belfast Brigade emerged from the local "defence associations" active in the city at the beginning of the Troubles. It subsequently emerged as the largest of the UDA's six brigades and expanded to cover an area much wider than its initial South Belfast borders.

Origins

[edit]In the first days of the Troubles a number of local "defence associations" were established across Belfast by Protestants, ostensibly to protect against attacks from the IRA. Whilst South Belfast had fewer interface areas than the west or north of the city it nonetheless followed suit. An early example of such a group was the Donegall Road defence committee, although in contrast to the likes of the Shankill Defence Association in the west of the city, this group was loyal to Ian Paisley.[1]

According to one unidentified founder member of the group, the meeting that saw the establishment of the UDA at Aberdeen Street Primary School on the Shankill Road in 1971 was not attended by any groups from the south of the city.[2] Southern representatives however attended two subsequent meetings and came on board as part of the new group.[3] As such when the UDA in Belfast adopted a more formal structure the following year South Belfast was determined as one of the city's four battalions, along with East, North and West Belfast. Each of these areas was promoted to brigade status at an undetermined date soon afterwards.[4] The earliest centre of activity for the UDA in South Belfast was Sandy Row close to Belfast city centre, although it soon spread out to other areas of the city as well as to nearby towns such as Lisburn, Dromara and Ballynahinch.[4]

Sandy Row UDA

[edit]

Sammy Murphy emerged as the commander in Sandy Row, using the local Orange Hall as his headquarters.[5] In June 1972 he took the lead in a stand-off with republicans in Lenadoon, an area in the southwest of the city but too far removed from the Shankill Road to be considered part of the West Belfast jurisdiction. With the Provisional IRA (IRA) on ceasefire the UDA hoped to use the incident to force them to break their truce to end negotiations between the IRA and the British government.[6] With Protestant residents intimidated out of Horn Drive in Lenadoon, the IRA wanted to move in Catholics who had suffered a similar fate in other parts of the city. Murphy brought in a force of UDA members to prevent this and a stand-off ensued between the UDA and the Catholic would-be residents, with the British Army also in attendance. After a while the Catholics began throwing stones at the UDA.[6]

Soon IRA snipers entered the fray and a gun battle between the republicans and the British Army ensued. The UDA eventually withdrew. While Murphy believed his plan for bringing down the IRA ceasefire had been a success,[6] the IRA leadership had already warned British government negotiators that the ceasefire would finish if the British Army failed to protect the homeless Catholics in Lenadoon. Provisional IRA Belfast Brigade leaders Seamus Twomey and Brendan Hughes, who were especially eager to end the ceasefire because they believed the British were acting in bad faith, had laid careful plans to end it at Lenadoon if the soldiers entered the fray on the side of the loyalists.[7][page needed][8][page needed]

The UDA in Sandy Row were also involved in "rompering", a nickname given by the UDA to the slow, torture-driven killings of kidnapped victims. On 30 August 1972 members of the group, as well as leading Woodvale Defence Association figure Ernie Elliott, kidnapped Catholic former British soldier Patrick Devaney before taking him to Sandy Row where he was hung upside down from a beam and beaten with hammers before being shot in the back of the head.[9] The same group was responsible for one of the early UDA-on-UDA killings in December 1972 when members of the group shot and killed Ernie Elliott after a drunken argument about weapons that Elliott's men had loaned to the southern contingent.[10] According to later eyewitness reports Elliott had entered a UDA club in the area and began waving a gun about, with the weapon discharging during a struggle when others attempted to disarm him.[11] Another "rompering" death was also carried out in the area in July 1974 when a 32-year-old Protestant single mother Ann Ogilby was killed by a UDA women's unit based in the area.[12] Ogilby's interned boyfriend William Young was the local commander of the Donegall Pass UDA which came under the South Belfast UDA's auspices. Ogilby had spread rumours about Young's wife, who was a member of the Sandy Row women's UDA, that resulted in her fatal punishment beating.[13] The commander of the Sandy Row women's UDA unit was Elizabeth "Lily" Douglas of City Street. She was among the ten women convicted of Ogilby's murder. The unit was disbanded by the UDA following the killing.[12][14]

The UDA in Sandy Row had garnered a reputation for the unruly and drunken nature of its members with a "day of action" on 7 February 1973 organised by the Ulster Vanguard and the Loyalist Association of Workers descending into chaos in the area. With few becoming involved in a proposed withdrawal of labour, the local UDA undertook a series of assaults and car burnings, before setting fire to a shop on the corner of Sandy Row. They then shot at the fire brigade when they arrived, killing Brian Douglas, a Protestant fireman, and precipitating a night of rioting and violence in both the south and east of the city.[15] The group also attacked nearby Durham Street, killing two Catholics from the area in quick succession in March 1973.[16] Robert Fisk, who worked as the Belfast correspondent for The Times from 1972–75, suggested that the Sandy Row UDA was one of the most bellicose of all the paramilitary units in Belfast during this period.[5] Henry McDonald and Jim Cusack confirmed this, declaring that the Sandy Row and Donegall Pass UDA were almost out of control at the time, with both its men and women inured to killings and beatings.[17]

Wider emergence

[edit]Towards the end of 1972 the UDA began to increase in importance in other areas of South Belfast, with the "Village" area of the Donegall Road becoming another centre of activity. A hit team was established here and in January 1973 they carried out four murders of Catholic youths from nearby West Belfast in quick succession. The youngest victim, Peter Watterson (aged 15), was mortally wounded in a drive-by shooting outside his mother's shop on the Falls Road/Donegall Road junction.[18] Soon afterwards however the IRA retaliated by capturing local commander Francis "Hatchet" Smith in Roden Street, close to his home, and fatally shooting him.[19] With Smith dead, the UDA in South Belfast, which by that time was recognised as a brigade, stepped up its activity, kidnapping 14-year-old Philip Rafferty from his home in Andersonstown and taking him to the Giant's Ring, where he was murdered.[19] Gabriel Savage, a seventeen-year-old, was killed in similar circumstances soon afterwards.[16]

Other units began to emerge in Taughmonagh and Dunmurry, with the former responsible for killing Daniel Rouse in June 1973, in an attack which saw the 17-year-old beaten severely before being shot.[20] The brigade was also active during the Ulster Workers' Council strike of 1974, with the Village team killing a Catholic university student, Michael Mallon, at the height of strike.[21] Sammy Murphy and the Sandy Row UDA took a belligerent stance during the strike. They almost came to direct confrontation with the British Army over the removal of UDA roadblocks in the area and had made preparations to use force had the British Army smashed them. Murphy, who was described in military press releases as a community leader, successfully negotiated with the soldiers to defuse the explosive situation.[5]

Gerard McWilliams, a young hippy from a Catholic background living in the Lisburn Road, was beaten and stabbed to death in an entry near his home by South Belfast brigade members in September 1974 as he returned from a night out at the Club Bar, a popular student and bohemian venue near Queen's University Belfast.[22] Two months later a unit from Sandy Row shot and killed a bouncer from the same bar, which was Catholic-owned but entertained a mixed clientele.[23] Similar attacks continued into 1975, with a Sandy Row gunman killing a young Catholic builder on nearby Great Victoria Street, before another attack by the Sandy Row unit on 9 February when they entered St Bride's Catholic Church on the Malone Road, a popular target for vandalism attacks by local loyalist youths, and killed two students in attendance.[24] These killings helped to set off a bloody period over the following two years when both republican and loyalist paramilitary groups were highly active in tit-for-tat sectarian killings.[24]

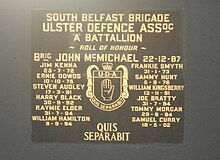

John McMichael

[edit]1977-84

[edit]

With South Belfast formalised as a brigade, Lisburn-based John McMichael emerged as the brigadier and, due to his closeness to UDA leader Andy Tyrie, soon became one of the most prominent figures within the wider movement.[25] Following the heavy activity of the years before, under the guidance of McMichael and Tyrie the UDA slowed down their run of killings. They were responsible for the deaths of three Catholics in 1977 and two in 1978.[26]

This changed in 1979, when a group of commando units was formed within the UDA under the name Ulster Defence Force (UDF), in order to take advantage of British Intelligence Corps documents that the UDA had obtained detailing the whereabouts of several republican leaders. Although the UDF was officially outside the UDA's brigade structure it was under the overall command of McMichael and included several of his most trusted South Belfast Brigade lieutenants within its ranks.[27] A notable action by the UDF, an attack on the home of Bernadette McAliskey, was carried out by South Belfast members of the UDF, including McMichael's closest confidante Ray Smallwoods.[28] Tom Graham of Lisburn and Andrew Watson from Seymour Hill, Dunmurry, both parts of the South Belfast Brigade area, were subsequently convicted and imprisoned along with Smallwoods for the attack.[29] When news of the army intelligence list being in UDA possession was leaked to the press during the trial, the UDF project was abandoned amid awkward questions about military-UDA collusion.[28] McMichael was amongst a number of UDA leaders arrested during subsequent investigations into collusion, although no charges were brought against him.[30] With McMichael a candidate in the 1982 Belfast South by-election, the South Belfast Brigade scaled down its role.[31]

1985 until death

[edit]During the protests against the Anglo-Irish Agreement in 1985, the brigade became involved in a series of sectarian petrol bomb attacks on the homes of Catholics in Lisburn.[32] McMichael also led a team based in Taughmonagh that had the job of organising a fire-bombing campaign against shops and businesses in the Republic of Ireland.[33] On 7 February 1987 this group detonated two bombs in Dublin and Donegal, causing £2 million worth of damage and garnering wide coverage in the Republic's media.[34] In a return to more basic sectarian killings, the South Belfast Brigade also added former East Belfast Brigade member Michael Stone to its ranks. Acting directly under McMichael's command, Stone carried out a series of killings of both republican political activists and other Catholic civilians.[35]

John McMichael was killed by a bomb attached to his car outside his Hilden Court home, in Lisburn's loyalist Hilden estate, on 22 December 1987, shortly before his fortieth birthday. He was on his way to deliver Christmas turkeys to the families of loyalist prisoners.[36] At 8:20pm, after he had turned on the ignition of his car and the vehicle slowly reversed down the driveway, the movement-sensitive switch in the detonating mechanism of the five pound booby-trap bomb attached to its underside was activated, and the device exploded. McMichael lost both legs in the blast and suffered grave internal injuries. He was rushed to Lagan Valley Hospital where he died two hours later.[37] The IRA claimed responsibility for the killing.[38]

Aftermath of killing

[edit]In the late 1980s James Craig, who had been an important figure in the West Belfast Brigade, moved over to the South Belfast Brigade after being ordered to leave the Shankill Road. He operated as the "chief collector" for the brigade and his presence ensured that they became as associated with racketeering as West Belfast had been during his tenure with that brigade.[39] Craig was killed in October 1988 as part of an internal UDA feud, with rumours rife that he had been involved in setting up McMichael's assassination. Rumours suggested that McMichael had indicated his desire to tackle racketeering shortly before his death, although this suggestion is rejected by Peter Taylor, who argues that as the rackets were profiting the brigade as a whole (as "chief collector" Craig was entitled to a percentage of everything[39]) there was no desire amongst the brigade leadership to cut off this source of revenue.[40] Nonetheless, a number of arrests were made relating to the brigade's rackets and in January 1990 a number of sentences were handed down to several of Craig's former associates, with Jackie McDonald sentenced to ten years imprisonment for blackmail, intimidation and making threats to kill.[41]

Towards ceasefire

[edit]Following the deaths of McMichael and Craig, the UDA entered a period of disarray with much of the old leadership, including Tyrie, removed. One of Tyrie's last acts was to promote Jackie McDonald, at the time an unpopular figure due to his associations with Craig, to the role of South Belfast brigadier.[42] His tenure proved short-lived however, due to the aforementioned conviction in 1990 in relation to his links to Craig. McDonald did oversee one prominent killing that was implicated in collusion investigations. On 25 August 1989 Loughlin Maginn, a Catholic from Rathfriland who was suspected by local loyalists of being an IRA member despite a lack of evidence, was killed by the South Belfast UDA. In a later interview McDonald would state he was sure Maginn was an IRA member, stating that his source was intelligence reports he had received from the Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR). The killing was investigated as part of the Stevens Inquiries into allegations of collusion and it was determined that contact between UDR and UDA members had been instrumental in the murder. In March 1992 four men were sentenced to life for the murder, Geoffrey McCullough and Edward Jones of the UDA and Andrew Browned and Andrew Smith of the UDR.[43]

McDonald was succeeded as brigadier by Alex Kerr, also a native of Taughmonagh.[44] Kerr took over a brigade in an area where sectarian tensions were growing as the Catholic population of South Belfast had increased significantly and as a result more interface areas had sprung up.[45] In this climate the South Belfast Brigade, and in particular its Upper Ormeau members based in the Annadale flats, was to once again take a leading role in sectarian killings. Dominated by Joe Bratty, Thomas "Tucker" Annett, Raymond Elder and Stephen "Inch" McFerran, this group carried out a number of killings in the early 1990s. Emmanuel Shields, a Catholic civilian who lived close to the Annadale flats and who was known personally to members of the Upper Ormeau UDA, was killed at his home on 7 September 1990. Shields had been beaten by future members of Bratty's team when they were children and had escaped a shooting attack at his mother's home years earlier.[46]

In 1990 South Belfast members also killed Tommy Casey, a Sinn Féin activist, at his home in Cookstown.[47] Although somewhat removed from South Belfast, this killing was part of a wider expansion of the South Belfast Brigade which by the early 1990s had expanded into Mid-Ulster, where a brigade had existed on and off but had become moribund. South Belfast Brigade teams were based in South Down, County Tyrone, Lurgan and on the border at County Fermanagh, as well as Cookstown.[48] With these teams, Upper Ormeau, Lisburn and a combined Sandy Row/Village unit all active, the brigade was rivalled only by West Belfast in terms of ruthlessness in the early 1990s.[48] The Village unit carried out the killing of a Catholic taxi driver, John O'Hara, on 17 April 1991, as part of a new UDA-wide policy of ringing known Catholic taxi firms to book a taxi and then shooting the driver when they arrived.[49] A notorious Lisburn hitman, known by the codename "Gravedigger", was also active on 25 May 1991 conducted a high-profile killing when he led a team that gunned down Sinn Féin councillor Eddie Fullerton at his home in County Donegal.[50] The policy of attacking Sinn Féin politicians had been developed by Ray Smallwoods, who had been released from prison and taken on a prominent role in both the Ulster Democratic Party (UDP) and the UDA, and it was followed soon after by the killing of Sinn Féin Councillor Bernard O'Hagan in Magherafelt by the Lisburn unit.[51] The Lisburn unit expanded significantly in 1991-2, launching a recruitment drive amongst teenagers in schools within its area. It carried out two more killings in early 1992.[52]

In February 1992 the brigade carried out the Sean Graham bookmakers' shooting in which five Catholic civilians were killed in a gun attack on the Ormeau Road.[53] Other killings that the group carried out included that of Michael Gilbride, a Catholic taxi driver who had settled in the Lower Ormeau area but who was killed outside his parents' home on Fernwood Street, not far from Bratty's Annadale Flats base.[54][55] Donna Wilson, a Protestant and resident of Annadale Flats who had recently moved to the area from Tullycarnet in Dundonald was killed after residents had complained to Bratty in his role as local UDA commander about the noise of her stereo. Bratty assembled a team of ten men armed with baseball bats who broke in, beat her to death, seriously injuring three of her companions and wrecked the flat. In the end only a sixty-year-old who had led the complaints to Bratty was charged with relation to Wilson's death.[56] Bratty was also identified as the getaway driver for the attack in which Teresa Clinton, the wife of a Sinn Féin election candidate, was murdered in her lower Ormeau home.[57] Thomas Annett, who was the main gunman in the Clinton killing, was killed in 1996 on 12 July when he got into a row with fellow UDA members outside an Ormeau Road bar and ended up being kicked to death.[58][57] Bratty and Elder were ultimately killed by the IRA on 31 July 1994, shortly before its declaration of a ceasefire.[59] McFerran, who was later revealed to have been an RUC Special Branch agent, was one of those who participated in the killing of Annett.[60]

The 1994 killings of Bratty and Elder saw an upswing in South Belfast Brigade activity as they carried out a number of "revenge" killings against Catholic targets.[61][62] Nonetheless, after the IRA ceasefire the UDA followed suit with the Combined Loyalist Military Command (CLMC) ceasefire, declared on 13 October 1994.

Post-ceasefire

[edit]As South Belfast brigadier, Alex Kerr was unenthusiastic about the Northern Ireland peace process and in particular about the publication of the Framework Documents in February 1995, dismissing their insistence on cross-border institutions as a united Ireland by stealth.[63] Growing close to UVF Mid-Ulster Brigade leader Billy Wright, Kerr began to attack the UDP for their alleged links to the illegal drugs trade and instructed brigade members to daub "Ulster Drugs Party" on the walls of the Donegall Road.[63] The brigade obeyed the ceasefire but, like their counterparts in the UDA South East Antrim Brigade, continued to take a leading role in sectarian intimidation, in particular targeting the few Catholic families who lived in the loyalist Blacks Road enclave, close to Lenadoon.[64] Kerr meanwhile drew closer to Wright and appeared publicly with him during the Drumcree conflict in 1996.[65] A meeting of the CLMC on 28 August 1996 agreed that both Kerr and Wright should be expelled from their respective organisations. The two then pooled their resources in a new dissident group, the Loyalist Volunteer Force (LVF).[66]

Jackie McDonald was again appointed brigadier, having been released from prison. McDonald faced an early challenge as relations with the local Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) deteriorated and threatened to break out into a loyalist feud. Robert "Basher" Bates had been a member of the notorious Shankill Butchers and one of his killings had been that of UDA member James Curtis Moorhead, with whom he had got into an argument in a Shankill bar in 1977. Having become a born-again Christian, Bates was released from prison and took a job at the Ex-Prisoners Interpretative Centre on the Woodvale Road. Whilst outside the centre on 11 June 1997 a relative of Moorhead, who was himself a UDA member, approached Bates and shot him dead.[67] Well-known locally, the killer was quickly identified and the UVF demanded he be given into their custody. However, following a meeting of the UDA's governing Inner Council (which McDonald, as South Belfast brigadier, attended) it was decided that the killer, who was highly regarded in the UDA, would be expelled from the Shankill and transferred to Taughmonagh as a member of the South Belfast Brigade.[67] An attempt to kill him outside a bar on Sandy Row followed, leading to sour relations between the Sandy Row UDA and the Donegall Pass UVF.[68]

In 1997, a leading member of the Dunmurry UDA, Brian Morton, described in some contemporary reports as being the brigade's second-in-command, was killed when a pipe bomb he was making exploded prematurely.[69] As part of a series of tit-for-tat killings in 1998, two members of the brigade, Jim Guiney and Robert Dougan, were killed by republicans. Both men were close friends of McDonald.[70] The UDA retaliated for the former attack by killing Catholic taxi-driver Larry Brennan on the Ormeau Road.[71] Dougan, the commander of the UDA in Suffolk, was killed in retaliation for the killing of another taxi driver, John McColgan, whose death the IRA blamed on the Suffolk UDA.[72] The spell of violence abated with the announcement of the Good Friday Agreement soon afterwards, with McDonald one of its main supporters within the UDA.[73]

Feud with West Belfast Brigade

[edit]Having emerged as the strongest pro-Agreement voice within the UDA, McDonald was soon on a collision course with his opposite number in West Belfast, Johnny Adair, who was close to the LVF. Whilst supporting the Orange Order's desire to march through nationalist areas, McDonald was a lot less enthusiastic than Adair about getting involved in the Drumcree conflict. McDonald felt that mainstream unionist parties were playing too much of a role in Drumcree and publicly condemned their tendency to link up with loyalist paramilitaries when it suited them only to later drop them when their usefulness had expired.[74] Similarly he was unconvinced by a series of vandalism attacks on loyalist areas in Belfast in late June by three carloads of "republicans", feeling that the missile-throwing youths were actually members of Adair's C Company sent to stir up sectarian hatred and win support for Adair's Drumcree strategy.[75]

McDonald was one of a number of brigadiers to accept Adair's invitation to a "Loyalist Day of Culture" on the Shankill Road on 19 August 2000 but was shocked to find that C Company had used the day to drive UVF members and their families from the road, even attacking the homes of such UVF "elder statesmen" as Gusty Spence and Winston Churchill Rea. At the culmination of the day, McDonald and other brigadiers, as well as Deputy Lord Mayor of Belfast Frank McCoubrey, were brought onto a makeshift stage where C Company members emerged and fired machine guns into the air in a show of strength.[76] McDonald had no desire to feud with the UVF and told his men to leave the Shankill that evening.[77] He promptly contacted his opposite number in the South Belfast UVF and concluded a pact that their members would not attack each other.[78]

Even when the initial feud cooled, the enmity between McDonald and Adair continued to simmer and in Inner Council meetings the two frequently clashed as, according to one veteran loyalist, "Jackie was the only one with the balls to stand up to him".[79] Nonetheless, when Adair was released from prison on 15 May 2002, McDonald, arguing that he deserved a second chance and hoping that his return to prison may have mellowed him, was one of the brigadiers to appear at Adair's Boundary Way home and welcome him back in front of the television cameras.[80]

The public display of amity between McDonald and Adair did not result in improved relations as time passed. On 14 September 2002, East Belfast LVF man Stephen Warnock was killed by the Red Hand Commando and immediately afterwards Adair, seeing an opportunity to strike back at a rival, went to his family home to inform visiting LVF members that the killing had been actually ordered by Jim Gray. With Adair's encouragement, an LVF hit team waited for Gray to appear at Warnock's house where, after he paid his respects to the family, he was shot in the face as he left. Gray was seriously injured but survived the attack.[81]

McDonald called a crisis meeting of brigadiers, including Adair, at Sandy Row but it failed to reach a conclusion as Adair denied involvement in the attack on Gray.[82] As soon as the meeting was over, Adair drove to Ballysillan in north Belfast to meet with allies in the LVF, although he was unaware that a mainstream UDA team were following him and recording his movements.[83] When McDonald was told about this second meeting he secured agreement with the other brigadiers that Adair should be expelled from the UDA.[82] Tension simmered for the next few months with little real fighting although McDonald threw a ring of steel around his Taughmonagh stronghold and even obtained an air raid siren to be sounded if any C Company members attempted to enter the estate.[84]

The killing of John Gregg and his associate Rab Carson by C Company in Sailortown on 1 February 2003 finally led to a showdown, with McDonald taking charge of the anti-Adair faction. McDonald quickly got word to A and B Company of the West Belfast UDA, covering the Highfield estate and Woodvale areas of the Greater Shankill and nominally under Adair's command, that Adair was to be removed and secured the loyalty of these two groups. He also told them to set up an office on the Shankill's Heather Street Social Club as a safe house where members of C Company could defect back to the mainstream UDA.[85]

At around 1am on 6 February 2003, about 100 heavily armed UDA members invaded the lower Shankill and set upon the twenty or so members of C Company who had remained loyal to Adair. his family and his close ally John White, ending his spell in charge on the Shankill.[86] Several weeks later McDonald organised a "battle of the bands" (competition between loyalist flute bands) at which he made it clear that unity had been re-established. He then received a standing ovation from those present as, marching behind a masked man carrying an AK 47, McDonald led the other five brigadiers onto the stage.[87] The feud had effectively made McDonald de facto head of the UDA and had shifted power away from the west of the city to make the South Belfast Brigade the movement's most important.

Subsequent activity

[edit]As head of both the South Belfast Brigade and effective leader of the UDA McDonald sought to move the group away from violence and announced in 2007 that the Ulster Freedom Fighters, a codename used by the UDA to refer to its killing wing, was to be stood down.[88] McDonald advocated decommissioning of UDA weapons although on this point he faced opposition from some of his fellow brigadiers, with Billy McFarland telling him that his North Antrim and Londonderry Brigade could not support the initiative.[89] McDonald also moved against others within the wider UDA whom he saw as a threat to his support for the peace process and in 2006 members of the South Belfast Brigade were moved across town to help force the dissident Shoukri brothers out of their north Belfast stronghold.[90] South Belfast Brigade members would return to the area in 2011 to again remove Shoukri supporters.[91] On Remembrance Day 2007 a UDA rally was held in Sandy Row at which it was announced that the South Belfast Brigade's war was over and that "the ballot box and the political institutions must be the greatest weapons", with McDonald declaring his support for the work of the Ulster Political Research Group.[92]

In 2012 McDonald faced criticism from the wider UDA and from within his own brigade after being photographed in attendance at the funeral of veteran IRA man Harry Thompson. In particular he was condemned by hard-liners for being pictured walking with Martin Ferris.[93] Eventually the leadership of the West Belfast Brigade began to link up with hard-liners in North Belfast in an attempt to form a new anti-McDonald alliance. In 2013 it was reported in the Belfast Telegraph that the West Belfast Brigade had become so associated with criminality and racketeering that McDonald and his close allies Jimmy Birch (East Belfast Brigade leader) and John Bunting (North Belfast brigadier), no longer felt able to deal with the western leadership. Tensions had been further stoked by a graffiti campaign against Bunting's leadership on the York Road, in which expelled members of the North Belfast Brigade, who had come under the wing of their counterparts in the west, called for Bunting's removal as brigadier.[94] The feud was confirmed in December 2013 when a UDA statement was released acknowledging the existence of a dissident tendency within the North Belfast Brigade but confirming support for Bunting's leadership. However, whilst the statement was signed by McDonald and Birch, no representative of the West Belfast Brigade had added their signature.[95] The North Belfast rebels subsequently named Robert Molyneaux, a convicted killer and former friend of Bunting's closest ally John Howcroft, as their preferred choice for Brigadier.[96] Bunting's opponents criticised his alleged heavy-handed approach, particularly towards Tiger's Bay residents, while his supporters claimed that Bunting's attempts to tackle the drugs trade in the area were the real reason behind the attempts to remove him.[97] McDonald meanwhile faced further calls to stand down from his opponents, with reports in the press suggesting that the leadership of the North Antrim and Londonderry Brigade were ready to declare their support for a West Belfast-led anti-McDonald initiative.[98]

As the feud rumbled on Bunting became a target for a number of attacks. In May 2014 Bunting was attacked in Tiger's Bay by a group of opponents. During the brawl Bunting was knocked unconscious and had his mobile phone stolen. Bunting had been visiting the home of one of his internal critics at the time of the incident.[99] In August 2014 as Bunting drove along Duncairn Gardens, a street separating Tiger's Bay from the republican New Lodge area his car was damaged by a pipe bomb thrown at it.[100] Tiger's Bay had emerged as the stronghold of the anti-Bunting faction.[101]

Soon after the latter attack former North Belfast brigadier William Borland, who had become associated with the pro-Molyneaux wing, was attacked with a breeze block and shot in the leg close to his home in Carr's Glen. Following the attack both Bunting and Howcroft were arrested on suspicion of involvement.[102] Along with another associate they were charged with attempting to murder Borland and Andre Shoukri and were remanded in custody.[103] As is standard within the UDA whilst in custody Bunting had to relinquish his role as brigadier although his replacement, a close friend of McDonald's from Taughmonagh identified only as the "Burger King Brigadier" due to his weight, has been reported as merely a figurehead with no actual power.[103]

In September 2014 it was reported in the Belfast Telegraph that the leaders of the UDA in North, East and South Belfast, as well as the head of the Londonderry and North Antrim Brigade had met to discuss the feud as well as the schism with the West Belfast Brigade. According to the report they agreed that West Belfast Brigade members loyal to the wider UDA should establish a new command structure for the brigade which would then take the lead in ousting Mo Courtney, Jim Spence and Eric McKee from their existing leadership positions. It was also stated that the West Belfast breakaway leaders had recruited Jimbo Simpson, a former North Belfast brigadier driven out of Northern Ireland over a decade earlier, and were seeking to restore him to his former role.[104] This followed the rejection of earlier overtures to West Belfast brigadier Matt Kincaid as he opted to back Spence and Courtney.[105] William Borland, was shot Dead in 2016.

As of 2015 the feud remains unresolved, with McDonald's chosen North Belfast brigadier facing a dissident leadership based in Tiger's Bay with Bill Hill, a leading figure in the Belfast City Hall flag protests acting as spokesman for the dissidents.[106] McDonald remains in charge of the South Belfast Brigade, albeit with several stern critics within the wider UDA.

In an incident unconnected to the feud the brigade's former commander in the Belvoir area of Newtownbreda, Colin "Bap" Lindsay, was killed at his home after being hacked to death with his own sword.[107] Fellow UDA man Stanley Wightman died of his injuries soon afterwards, with Albert Armstrong, also a UDA member and a known associate of Lindsay and Wightman, was arrested and charged with the killings.[108] Lindsay was buried on 18 July, with the funeral attended by Jackie McDonald, who was described in the press as a "close friend of the deceased".[109] The funeral proved controversial due to the presence of paramilitary insignia.[110]

Brigadiers

[edit]- John McMichael 1970s–1987

- Jackie McDonald 1988–1989

- Alex Kerr 1989–1995

- Jackie McDonald 1995–date

Bibliography

[edit]- Bruce, S., The Red Hand: Protestant Paramilitaries in Northern Ireland, Oxford University Press, 1992

- McDonald, H. & Cusack, J., UDA: Inside the Heart of Loyalist Terror, Penguin Ireland, 2004

- Taylor, P., Loyalists, Bloomsbury, 2000

- Wood, I. S., Crimes of Loyalty: A History of the UDA. Edinburgh University Press, 2006

References

[edit]- ^ McDonald & Cusack, p. 15

- ^ Bruce, pp. 49-50

- ^ McDonald & Cusack, p. 20

- ^ a b McDonald & Cusack, p. 24

- ^ a b c Fisk, Robert (1975). The Point of No Return: the strike which broke the British in Ulster. London: Times Books. pp. 145-148

- ^ a b c McDonald & Cusack, p. 31

- ^ Peter Taylor, The Provos: The IRA and Sinn Fein, A&C Black, 2014

- ^ Ed Moloney, A Secret History of the IRA, Penguin UK, 2007

- ^ McDonald & Cusack, p. 42

- ^ Bruce, p. 67

- ^ McDonald & Cusack, p. 34

- ^ a b Elizabeth Douglas, the Sandy Row executioner

- ^ "Ann Ogilby was beaten to death by a gang of UDA women - why would they come forward and tell all now?". Belfast Telegraph. Henry McDonald. 1 December 2013 Retrieved 14 June 2015

- ^ "Women Loyalist Paramilitaries in Northern Ireland: Duty, Agency and Empowerment - a Report From the Field". All Academic Research. Sandra McEvoy. 2008. p.16 Retrieved 14 June 2015

- ^ McDonald & Cusack, p. 48

- ^ a b McDonald & Cusack, p. 54

- ^ McDonald & Cusack, pp.57-58

- ^ McDonald & Cusack, pp. 52-53

- ^ a b McDonald & Cusack, p. 53

- ^ McDonald & Cusack, p. 59

- ^ McDonald & Cusack, p. 76

- ^ McDonald & Cusack, p. 90

- ^ McDonald & Cusack, p. 91

- ^ a b McDonald & Cusack, p. 94

- ^ McDonald & Cusack, pp. 103-105

- ^ McDonald & Cusack, p. 115

- ^ McDonald & Cusack, pp. 116-117

- ^ a b McDonald & Cusack, p. 118

- ^ Murray, Raymond (1990). The SAS in Ireland. Mercier Press. p.263

- ^ McDonald & Cusack, p. 124

- ^ McDonald & Cusack, p. 121

- ^ Bruce, p. 237

- ^ McDonald & Cusack, p. 134

- ^ McDonald & Cusack, pp. 134-136

- ^ Michael Stone, None Shall Divide Us, John Blake Publishing, 2003, pp. 66-79

- ^ Wood, p. 128

- ^ McDonald & Cusack, p. 150

- ^ McDonald & Cusack, p. 157

- ^ a b Bruce, pp. 246-247

- ^ Taylor, pp. 170-171

- ^ Taylor, p. 171

- ^ Taylor, p. 170

- ^ Taylor, pp. 205-206

- ^ David Lister & Hugh Jordan, Mad Dog: The Rise and Fall of Johnny Adair and 'C' Company, Edinburgh: Mainstream, 2004, p. 127

- ^ McDonald & Cusack, p. 161

- ^ McDonald & Cusack, p. 184

- ^ McDonald & Cusack, p. 186

- ^ a b McDonald & Cusack, p. 187

- ^ McDonald & Cusack, pp. 188-189

- ^ McDonald & Cusack, pp. 192-193

- ^ McDonald & Cusack, p. 205

- ^ McDonald & Cusack, pp. 221-222

- ^ Taylor, p. 218

- ^ McDonald and Cusack, p. 238

- ^ Sutton Index of Deaths 1992, cain.ulst.ac.uk; accessed 23 November 2015.

- ^ McDonald and Cusack, pp. 238-239

- ^ a b McDonald and Cusack, p. 255

- ^ Guilty plea meant loyalist's double life remained secret Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, The Irish News, 15 April 2007

- ^ McDonald & Cusack, p. 269

- ^ Barry McCaffrey. "Guilty plea meant loyalist's double life remained secret", cain.ulst.ac.uk; retrieved 28 May 2015.

- ^ Taylor, p. 231

- ^ Wood, p. 189

- ^ a b McDonald & Cusack, p. 278

- ^ McDonald & Cusack, pp. 279-280

- ^ McDonald & Cusack, pp. 281-282

- ^ McDonald & Cusack, p. 284

- ^ a b McDonald & Cusack, p. 290

- ^ McDonald & Cusack, p. 291

- ^ Wood, p. 201

- ^ Taylor, p. 246

- ^ McDonald & Cusack, pp. 297-298

- ^ McDonald & Cusack, p. 299

- ^ McDonald & Cusack, p. 302

- ^ McDonald & Cusack, p. 319

- ^ McDonald & Cusack, pp. 319-320

- ^ McDonald & Cusack, pp. 326-327

- ^ McDonald & Cusack, p. 330

- ^ McDonald & Cusack, p. 336

- ^ McDonald & Cusack, p. 370

- ^ Lister & Jordan, Mad Dog, p. 303

- ^ McDonald & Cusack, pp. 371-372

- ^ a b McDonald & Cusack, p. 374

- ^ Lister & Jordan, Mad Dog, pp. 318-319

- ^ McDonald & Cusack, p. 375

- ^ McDonald & Cusack, pp. 383-384

- ^ McDonald & Cusack, p. 386

- ^ McDonald & Cusack, p. 395

- ^ "Jackie McDonald is widely regarded as the UDA's most senior figure. A resident of the Taughmonagh estate in Belfast, he was convicted of extortion in the 1980s". Belfast Telegraph. 16 December 2009. Archived from the original on 25 February 2016. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- ^ "McDonald advocates decommissioning of UDA weapons". Sunday Life. 30 August 2009. Archived from the original on 22 February 2016. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ^ "Tensions high over UDA move". The News Letter. 30 May 2006. Archived from the original on 22 February 2016. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ^ "Fears grow of dust-up in the UDA". Sunday Life. 9 January 2011. Archived from the original on 25 February 2016. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ^ Cambridge, Jonathan (12 November 2007). "Sleeping giant awakes to the sound of a Carpenters ballad". Belfast Telegraph. Archived from the original on 22 February 2016. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ^ Murray, Alan (15 July 2012). "Funeral Pic Caused So Much Anger". Belfast Telegraph. Archived from the original on 25 February 2016. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ^ UDA finished, says loyalist paramilitary terror group leader, belfasttelegraph.co.uk; accessed 23 November 2015.

- ^ As UDA confirms major split, a dangerous tussle for power is now brewing, belfasttelegraph.co.uk; accessed 23 November 2015.

- ^ UDA feud escalates over bid to oust north Belfast 'brigadier' John Bunting

- ^ Barnes, Ciaran (8 December 2013). "The Brute Brigadier; UDA Power Struggle Rival Factions at War Double Killer Is the Man Dissidents Want to Install as New UDA Chief in North Belfast". Belfast Telegraph. Archived from the original on 29 February 2016. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ^ Murray, Alan (1 December 2013). "Move to Oust McDonald as UDA Leader". Sunday Life. Archived from the original on 23 February 2016. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ^ Devlin, Patricia (25 May 2014). "Granny Claims USA Boss Attacked Her; Terror Boss in Brawl New Allegations Pensioner Says Bunting Threw Her to the Ground". Belfast Telegraph. Archived from the original on 29 February 2016. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ^ Barnes, Ciaran (10 August 2014). "UDA Fury Over Bunting Attack: Hit Tension Among Splinter Groups Chiefs Threat of Retaliation on Rival Tigers Bay Faction". Belfast Telegraph. Archived from the original on 29 February 2016. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ^ Barnes, Ciaran (17 August 2014). "Feud Splits the UDA in Shankill; Row Intensifies Following UDA Shooting at Home of Alleged Dissident Supporter". Sunday Life. Archived from the original on 23 February 2016. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ^ Fitzmaurice, Maurice (22 August 2014). "Bunting and Pal Held in UDA Feud Shooting". Daily Mirror.

- ^ a b Murray, Alan (31 August 2014). "Shoukri Seeks Sinn Fein Meet; Exclusive Rival Factions at War Ex-UDA Chief wants Probe into Murder Bid". Sunday Life. Archived from the original on 10 April 2016. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ^ Barnes, Ciaran (14 September 2014). "UDA Call an 'AGM' to End Faction Feuds". Belfast Telegraph. Archived from the original on 28 March 2015. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ^ Barnes, Ciaran (2 February 2014). "UDA Chiefs' Unity Talks Are a Flop". Belfast Telegraph. Archived from the original on 28 March 2015. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ^ "Loyalist Stand-off in Seaside Bar; Deposed UDA Chief Bunting in Clash with Fierce Rival Hill". Belfast Telegraph. 19 April 2015. Archived from the original on 17 November 2018. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ^ "Ulster Defence Association member murdered in Belfast". The Guardian. 8 July 2015. Archived from the original on 19 April 2021.

- ^ Stanley Wightman dies after Belvoir estate 'sword' attack

- ^ Funeral is held for slain terror chief Colin 'Bap' Lindsay

- ^ Police criticised over privacy request at UDA man Colin 'Bap' Lindsay's funeral