10th Mountain Division

| 10th Mountain Division | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

10th Mountain Division Shoulder Sleeve Insignia | |||||

| Active | 1943–1945 1948–1958 1985–present | ||||

| Country | |||||

| Branch | |||||

| Type | Light infantry | ||||

| Size | Division | ||||

| Part of | |||||

| Garrison/HQ | Fort Drum, New York | ||||

| Nickname(s) | The Tenth Legion, The Mountaineers | ||||

| Motto(s) | Climb to Glory[1] | ||||

| Colors | Red and Blue | ||||

| Engagements | |||||

| Commanders | |||||

| Current commander | Major General Scott M. Naumann | ||||

| Deputy Commanding General – Operations | Brigadier General Kendall J. Clarke | ||||

| Deputy Commanding General – Readiness | Colonel Matthew W. Braman | ||||

| Command Sergeant Major | Command Sergeant Major Brett W. Johnson | ||||

| Notable commanders | George P. Hays James Edward Moore Thomas L. Harrold Philip De Witt Ginder Barksdale Hamlett James L. Campbell Franklin L. Hagenbeck Lloyd Austin Benjamin C. Freakley Michael L. Oates James L. Terry Mark A. Milley | ||||

| Insignia | |||||

| Distinctive unit insignia of the Division's Headquarters Battalion |  | ||||

| Subdued shoulder sleeve insignia worn on OCP-ACU |  | ||||

| Combat service identification badge |  | ||||

| Division flag |  | ||||

| NATO Map Symbol |

| ||||

| US Infantry Divisions | ||||

|

The 10th Mountain Division (Light Infantry) is a light infantry division in the United States Army based at Fort Drum, New York. Formerly designated as a mountain warfare unit, the division was the only one of its size in the US military to receive specialized training for fighting in mountainous conditions. More recently, the 10th Mountain has advised and assisted Iraqi Security Forces in Iraq and People's Defense Units in Syria.

Originally activated as the 10th Light Division (Alpine) in 1943, the division was redesignated the 10th Mountain Division in 1944 and fought in the mountains of Italy in some of the roughest terrain in World War II. On 5 May 1945, the division reached Nauders, Austria, just beyond the Reschen Pass, where it made contact with German forces being pushed south by the U.S. Seventh Army. A status quo was maintained until the enemy headquarters involved had completed their surrender to the Seventh. On 6 May, 10th Mountain troops met the 44th Infantry Division of Seventh Army.[2]

Following the war, the division was deactivated, only to be reactivated and redesignated as the 10th Infantry Division in 1948. The division first acted as a training division and, in 1954, was converted to a full combat division and sent to Germany before being deactivated again in 1958.

Reactivated again in 1985, the division was designated the 10th Mountain Division (Light Infantry) to historically tie it to the World War II division and to also better describe its modern disposition. Since its reactivation, the division or elements of the division have deployed numerous times. The division has participated in Operation Desert Storm (Saudi Arabia), Hurricane Andrew disaster relief (Homestead, Florida), Operation Restore Hope and Operation Continue Hope (Somalia), Operation Uphold Democracy (Haiti), Operation Joint Forge (Bosnia and Herzegovina), Operation Joint Guardian (Kosovo), and several deployments as part of the Multinational Force and Observers (Sinai Peninsula).

Since 2002, the 10th Mountain Division has been the most deployed regular Army unit.[3] Its combat brigades have seen over 20 deployments, to both Iraq and Afghanistan, in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom. It took the nickname The Tenth Legion while deployed in Afghanistan in late 2001 into 2002.

History

[edit]World War I

[edit]The U.S. Army organized a 10th Division during World War I in July 1918 at Camp Funston, Kansas. It was redesignated the Panama Canal Division after the war and shares no connection with the 10th Mountain Division activated during World War II.[4]

This 10th Division was made up of Regular Army and National Army troops. It was commanded by Major General Leonard Wood, formerly the Chief of Staff of the United States Army and a Medal of Honor recipient. The drafted men assigned to the division chiefly came from Illinois, Kansas, Missouri, Nebraska, and South Dakota, although there were also small contingents from the United States at large.

The division consisted of a headquarters, headquarters troop, the 19th Infantry Brigade (41st and 69th Infantry Regiments), the 20th Infantry Brigade (20th and 71st Infantry Regiments), the 28th, 29th, and 30th Machine Gun Battalions, the 10th Field Artillery Brigade (28th, 29th, and 30th Field Artillery Regiments and 10th Trench Mortar Battery), the 210th Engineer Regiment, the 210th Field Signal Battalion, and the 10th Train Headquarters and Military Police (Ammunition, Engineer, Sanitary, and Supply Trains).

The division's advance detachment reached Brest, France, but due to the Armistice with Germany in November 1918 which ended hostilities, the rest of the division did not go overseas and was demobilized in February 1919.

Genesis of U.S. mountain troops

[edit]In November 1939, two months after World War II broke out in Europe, during the Soviet Union's invasion of Finland, Red Army efforts were frustrated following the destruction of two armored divisions by Finnish soldiers on skis.[5] The conflict caught global attention as the outnumbered and outgunned Finnish soldiers were able to use the difficult local terrain to their advantage,[6] severely hampering the Soviet attacks and embarrassing their military.[7] Upon seeing the effectiveness of these troops, Charles Minot "Minnie" Dole, the president of the National Ski Patrol, began to lobby the War Department of the need for a similar unit of troops in the United States Army, trained for fighting in winter and mountain warfare. In September 1940, Dole was able to present his case to General George C. Marshall, the Army Chief of Staff, who agreed with Dole's assessment, deciding to create a "Mountain" unit for fighting in harsh terrain. The U.S. Army authorized the formation of the platoon-sized Army Ski Patrol in November 1940. The first Patrol was formed at Camp Murray as part of the 41st Infantry Division under Lt. Ralph S. Phelps (later to become commanding General of the 41st).[8] The army, prompted by fears that its standing force would not perform well in the event of a winter attack on the Northeastern coast, as well as knowledge that the German Army already had three mountain warfare divisions known as Gebirgsjäger, approved the concept for a division.[9] This required an overhaul of U.S. military doctrine, as the concept of winter warfare had not been tested in the army since 1914.[10] At first, planners envisioned ten mountain divisions, but personnel shortages revised the goal to three. Eventually, the 10th Mountain Division would be the only one brought to active duty.[9] Military leaders continued to express concern about the feasibility of a division-sized mountain warfare unit until the fall of 1941,[11] when they received reports that Greek mountain troops had held back superior numbers of unprepared Italian troops in the Albanian mountains during the Greco-Italian War. The Italian military had lost a disastrous 25,000 men in the campaign because of their lack of preparedness to fight in the mountains.[12][13] On 22 October 1941, General Marshall decided to form the first battalion of mountain warfare troops for a new mountain division.[14] The Ski Patrol would assist in its training.[15]

On 8 December 1941, the day after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the subsequent American entry into World War II, the army activated its first mountain unit, the 87th Mountain Infantry Battalion (which was later expanded to the 87th Infantry Regiment) at Fort Lewis, Washington, south of Tacoma.[14] It was the first mountain warfare unit in U.S. military history.[16] The National Ski Patrol took on the unique role of recruiting for the 87th Infantry Regiment and later the division, becoming the only civilian recruiting agency in military history.[14] Army planners favored recruiting experienced skiers for the unit instead of trying to train standing troops in mountain warfare, so Dole recruited from schools, universities, and ski clubs for the unit.[17] The 87th trained in harsh conditions, including Mount Rainier's 14,411-foot (4,392 m) peak, throughout 1942 as more recruits were brought in to form the division.[18][19] Initial training was conducted by Olympian Rolf Monsen.[20] A new garrison was built for the division in central Colorado at Camp Hale, at an elevation of 9,200 feet (2,800 m) above sea level.[21][22]

World War II

[edit]

The 10th Light Division (Alpine) was constituted on 10 July 1943[23] and activated five days later at Camp Hale under the command of Brigadier General Lloyd E. Jones, with Brigadier General Frank L. Culin Jr. assigned as his assistant division commander (ADC).[24] At the time, the division had a strength of 8,500 out of the 16,000 planned, so the military transferred troops from the 30th, 31st, and 33rd Infantry Divisions along with volunteers from the National Guards of Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, New York, Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iowa, North and South Dakota, Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, Idaho, Utah and Washington (specifically, men who were from the Rocky Mountain and northern states, close to the 45th parallel north), to fill out the remainder of the division.[25] This lowered morale, and the division faced many difficulties in the new training, which had no established army doctrine.[22] The 10th Light Division was centered on regimental commands; the 85th, 86th, and 87th Infantry Regiments.[26] Also assigned to the division were the 604th, 605th, and 616th Field Artillery Battalions, the 110th Signal Company, the 710th Ordnance Company, the 10th Quartermaster Company, the 10th Reconnaissance Troop, the 126th Engineer Battalion, the 10th Medical Battalion, and the 10th Counterintelligence Corps Detachment.[26][27] The 10th Light Division was unique in that it was the only division in the army with three field artillery battalions instead of four.[26] It was equipped with vehicles specialized in snow operation, such as the M29 Weasel,[28] and winter weather gear, such as white camouflage and skis specifically designed for the division.[29][30] The division practiced its rock climbing skills in preparation for the invasion of Italy on the challenging peaks of Seneca Rocks in West Virginia.

On 22 June 1944, the division was shipped to Camp Swift, Texas, to prepare for maneuvers in Louisiana, which were later canceled. A period of acclimation to a low altitude and hot climate was thought necessary to prepare for this training.[31] On 6 November 1944, the 10th Division was redesignated the 10th Mountain Division.[32] That same month, the blue and white "Mountain" tab was authorized for the division's new shoulder sleeve insignia.[1] Also in November, the division received a new commander, Brigadier General George Price Hays, a Medal of Honor recipient and a distinguished veteran of World War I. On January 4, 1945 he received a promotion to major general.[33]

Italy

[edit]

The division sailed for the Italian front in two parts, with the 86th Infantry and support leaving Camp Patrick Henry, Virginia on 11 December 1944 aboard the SS Argentina and arriving in Naples, Italy on 22 December. The 85th and 87th Infantry left Hampton Roads, Virginia on 4 January 1945 aboard the SS West Point and arrived on 13 January 1945.[34] By 6 January, its support units were preparing to head to the front lines.[35] It was attached to Major General Willis D. Crittenberger's IV Corps, part of the American Fifth Army, commanded by Lieutenant General Lucian Truscott.[36] By 8 January, the 86th Infantry had moved to Bagni di Lucca near Mount Belvedere in preparation for an offensive by the Fifth Army to capture the mountain along with surrounding high ground, which allowed the Axis to block advances to Po Valley. Starting 14 January, the division began moving to Pisa as part of the Fifth Army massing for this attack.[34]

By 20 January, all three of the 10th's regiments were on or near the front line between the Serchio Valley and Mt. Belvedere. Col. Raymond C. Barlow commanded the 85th Regiment, Col. Clarence M. Tomlinson the 86th, and Col. David M. Fowler the 87th.[37]

Preliminary defensive actions in mid-February were followed by Operation Encore, a series of attacks in conjunction with troops of the 1st Brazilian Infantry Division, to dislodge the Germans from their artillery positions in the Northern Apennines on the border between Tuscany and Emilia-Romagna regions, in order to make possible the Allied advance over the Po Valley.[38] While the Brazilian division was in charge of taking Monte Castello and Castelnuovo di Vergato, the 10th Mountain Division was responsible for the Mount Belvedere area, climbing nearby Riva Ridge during the night of 18 February and attacking Mount Della Torraccia on 20 February. These peaks were cleared after four days of heavy fighting, as Axis troops launched several counterattacks in these positions.[39]

In early March, the division fought its way north of Canolle and moved to within 15 miles (24 km) of Bologna.[40] On 5 March, while Brazilian units captured Castelnuovo, the 85th and the 87th Infantry took respectively Mount Della Spe and Castel D'Aiano, cutting the Axis routes of resupply and communication into the Po Valley, setting the stage for the next Fifth Army offensive.[39] The division maintained defensive positions in this area for three weeks, anticipating a counteroffensive by the German forces.[40]

The division resumed its attack on 14 April, attacking Torre Iussi and Rocca Roffeno to the north of Mount Della Spe. On 17 April, it broke through the German defenses, which allowed it to advance into the Po Valley area.[39] It captured Mongiorgio on 20 April and entered the valley, seizing the strategic points Pradalbino and Bomporto.[40] The 10th crossed the Po River at San Benedetto Po on 23 April, reaching Verona 25 April, and ran into heavy opposition at Torbole and Nago.[40] After an amphibious crossing of Lake Garda, it secured Gargnano and Porto di Tremosine, on 30 April, as German resistance in Italy ended. The awarding winning documentary 2023 The Lost Mountaineers and chronicles the last days of actions for the 10th Mountain Division and focuses on the death of 25 soldiers from the 10th Mountain Division who drowned at Lake Garda on the night of April, 30, 1945 when their amphibious craft (DUKW) sank.[41] [42] [40] After the German surrender in Italy on 2 May 1945, the division went on security duty. On 5 May 1945 the division reached Nauders, Austria, just beyond the Reschen Pass, where it made contact with German forces being pushed south by the U.S. Seventh Army. A status quo was maintained until the enemy headquarters involved had completed their surrender to the Seventh. On the 6th, 10th Mountain Division troops met the 44th Infantry Division of the Seventh Army.[2] Between the 2nd and Victory in Europe Day on 8 May the 10th Mountain Division received the surrender of various German units and screened areas of occupation near Trieste, Kobarid, Bovec and Log pod Mangartom, Slovenia.[40] The division moved to Udine on 20 May and joined the British Eighth Army in preventing further westward movement of ground forces from the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.[43]

Casualties

[edit]- Total battle casualties: 4,072[44]

- Killed in action: 992[44]

- Wounded in action: 3,134[44]

- Missing in action: 38[44]

- Prisoners of war: 28[44]

Demobilization

[edit]Originally, the division was to be sent to the Pacific theater to take part in Operation Downfall, the invasion of mainland Japan, as one of the primary assault forces. However, Japan surrendered in August 1945 following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.[45] The division returned to the US two days later.[35] It was demobilized and inactivated on 30 November 1945 at Camp Carson, Colorado.[46] During World War II, the 10th Mountain Division suffered 992 killed in action and 4,154 wounded in action in 114 days of combat.[47] Soldiers of the division were awarded one Medal of Honor (John D. Magrath), three Distinguished Service Crosses, one Distinguished Service Medal, 449 Silver Star Medals, seven Legion of Merit Medals, 15 Soldier's Medals, and 7,729 Bronze Star Medals.[35] The division itself was awarded two campaign streamers.[35]

Cold War

[edit]In June 1948, the division was rebuilt and activated at Fort Riley, Kansas to serve as a training division. Without its "Mountain" tab, the division served as the 10th Infantry Division for the next ten years. The unit was charged with processing and training replacements in large numbers. This mission was expanded with the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950. By 1953, the division had trained 123,000 new Army recruits at Fort Riley.[48]

In 1954, the division was converted to a combat division once again, though it did not regain its "Mountain" status.[48] Using equipment from the deactivating 37th Infantry Division, the 10th Infantry Division was deployed to Germany, replacing the 1st Infantry Division at Würzburg, serving as part of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) defensive force. The division served in Germany for four years, until it was rotated out and replaced by the 3rd Infantry Division. The division moved to Fort Benning, Georgia, and was inactivated on 14 June 1958.[48]

Reactivation

[edit]On 13 February 1985, the 10th Mountain Division (Light Infantry) was reactivated at Fort Drum, New York.[48] In accordance with the Reorganization Objective Army Divisions plan, the division was no longer centered on regiments, instead two brigades were activated under the division. The 1st Brigade, 10th Mountain Division (commanded by then Colonel John M. Keane, later 4-Star General and Army Vice Chief of Staff) and Division Artillery were activated at Fort Drum, while the 2nd Brigade, 10th Mountain Division was activated at Fort Benning, moving to Fort Drum in 1988.[49] The division was also assigned a round-out brigade from the Army National Guard, the 27th Infantry Brigade.[50] The division was specially designed as a light infantry division able to rapidly deploy. In this process, it lost its mountain warfare capability, but its light infantry organization still made it versatile for difficult terrain.[51] Equipment design was oriented toward reduced size and weight for reasons of both strategic and tactical mobility.[48] The division also received a distinctive unit insignia.[1]

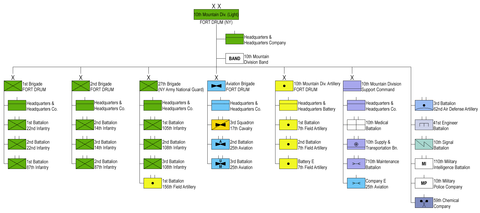

Structure in 1989

[edit]

At the end of the Cold War, the division was organized as follows:

- 10th Mountain Division (Light), Fort Drum, New York[52]

- Headquarters & Headquarters Company

- 1st Brigade

- 2nd Brigade[56]

- 27th Infantry Brigade (Light), Syracuse (New York Army National Guard)[59]

- Headquarters & Headquarters Company

- 1st Battalion, 108th Infantry, Auburn[60]

- 2nd Battalion, 108th Infantry, Syracuse[60]

- 3rd Battalion, 108th Infantry, Utica[60]

- 1st Battalion, 156th Field Artillery, Kingston, (18 × M101 105 mm towed howitzer)[61]

- 427th Support Battalion (Forward), Syracuse

- Troop E, 101st Cavalry, Buffalo

- 827th Engineer Company, Buffalo

- Aviation Brigade[62]

- Headquarters & Headquarters Company

- 3rd Squadron, 17th Cavalry (Reconnaissance)[63]

- 2nd Battalion, 25th Aviation (Attack)[64]

- Company C, 25th Aviation (General Support)[65]

- Company D, 25th Aviation (Assault)

- Division Artillery[66][67]

- Division Support Command

- Headquarters & Headquarters Company

- 10th Medical Battalion

- 10th Supply & Transportation Battalion[70]

- 710th Maintenance Battalion

- Company E, 25th Aviation (Aviation Intermediate Maintenance)

- 3rd Battalion, 62nd Air Defense Artillery

- 41st Engineer Battalion[71]

- 10th Signal Battalion[72]

- 110th Military Intelligence Battalion

- 10th Military Police Company

- 59th Chemical Company[73]

- 10th Mountain Division Band[74]

Contingencies

[edit]

In 1990, the division sent 1,200 soldiers to support Operation Desert Storm.[75] Two infantry platoons from the division were among those sent: 1st Platoon Bravo Company 1/22 and the 1/22 Scout Platoon. Once in Iraq, the scouts were sent home and First Platoon was left as a counterintelligence force. Performing three-man 24hr patrols through the remainder of their deployment, this platoon was widely regarded as the division's best at that time. Following a cease-fire in March 1991, the support soldiers began redeploying to Fort Drum through June of that year.[48]

Hurricane Andrew struck South Florida on 24 August 1992, killing 13 people, leaving another 250,000 homeless, and causing damages in excess of $20 billion. On 27 August 1992, the 10th Mountain Division assumed responsibility for Hurricane Andrew disaster relief as Task Force Mountain.[75] Division soldiers set up relief camps, distributed food, clothing, medical necessities, and building supplies, as well as helping to rebuild homes and clear debris. The last of the 6,000 division soldiers deployed to Florida returned home in October 1992.[48]

Operation Restore Hope

[edit]

On 3 December 1992, the division headquarters was designated as the headquarters for all Army Forces (ARFOR) of the Unified Task Force (UNITAF) for Operation Restore Hope. Major General Steven L. Arnold, the division Commander, was named Army Forces commander. The 10th Mountain Division's mission was to secure major cities and roads to provide safe passage of relief supplies to the Somali population suffering from the effects of the Somali Civil War.[75]

Due to 10th Mountain Division efforts, humanitarian agencies declared an end to the food emergency and factional fighting decreased.[76] When Task Force Ranger and the SAR team were pinned down during a raid in what later became known as the Battle of Mogadishu, the 10th Mountain Division provided infantry for the UN quick reaction force sent to rescue them. The 10th Mountain Division had two soldiers killed in the fighting, which was the longest sustained firefight by regular US Army forces since the Vietnam War.[51] The division began a gradual reduction of forces in Somalia in February 1994, until the last soldiers of the 2nd Battalion, 22nd Infantry returned to the United States in March 1994.[76]

Operation Uphold Democracy

[edit]

The division formed the nucleus of the Multinational Force Haiti (MNF Haiti) and Joint Task Force 190 (JTF 190) in Haiti during Operation Uphold Democracy.[75] More than 8,600 of the division's troops deployed during this operation.[77] On 19 September 1994, the 1st Brigade conducted the Army's first air assault from aircraft carrier USS Dwight D. Eisenhower. This force consisted of 54 helicopters and almost 2,000 soldiers. They occupied the Port-au-Prince International Airport. This was the largest Army air operation conducted from a carrier since the Doolittle Raid in World War II.[76]

The division's mission was to create a secure and stable environment so the government of Haitian President Jean-Bertrand Aristide could be reestablished and democratic elections held. After this was accomplished, the 10th Mountain Division handed over control of the MNF-Haiti to the 25th Infantry Division on 15 January 1995. The division redeployed the last of its soldiers who served in Haiti by 31 January 1995.[77]

Operation Joint Forge

[edit]In the fall of 1998, the division received notice that it would be serving as senior headquarters of Task Force Eagle, providing a peacekeeping force to support the ongoing operation within the Multi-National Division-North area of responsibility in Bosnia and Herzegovina.[77] Selected division units began deploying in late summer, approximately 3,000 division soldiers deployed. After successfully performing their mission in Bosnia, the division units conducted a transfer of authority, relinquishing their assignments to soldiers of the 49th Armored Division, Texas National Guard. By early summer 2000, all 10th Mountain Division soldiers had returned safely to Fort Drum.[77]

Operation Joint Guardian

[edit]Readiness controversy

[edit]During the 2000 presidential election, the readiness of the 10th Mountain Division became a political issue when George W. Bush asserted that the division was "not ready for duty." He attributed the division's low readiness to the frequent deployments throughout the 1990s without time in between for division elements to retrain and refit.[78] A report from the US General Accounting Office in July 2000 also noted that although the entire 10th Mountain Division was not deployed to the contingencies at once, "deployment of key components—especially headquarters—makes these divisions unavailable for deployment elsewhere in case of a major war".[79] Conservative think tank The Heritage Foundation agreed with these sentiments, charging that the US military overall was not prepared for war due to post-Cold War drawdowns of the US Military.[79] The Army responded that, though the 10th Mountain Division had been unprepared following its deployment as Task Force Eagle, that the unit was fully prepared for combat by late 2000 despite being undermanned.[80] Still, the Army moved the 10th Mountain Division down on the deployment list, allowing it time to retrain and refit.[78]

In 2002, columnist and highly decorated military veteran David Hackworth again criticized the 10th Mountain Division for being unprepared due to lack of training, low physical fitness, unprepared leadership, and low morale. He said the division was no longer capable of mountain warfare.[81]

War on Terrorism

[edit]Initial deployments and 2004 reorganization

[edit]

Following the 11 September 2001 attacks, elements of the division, including its special troops battalion and 1st Battalion, 87th Infantry Regiment (1-87th) infantry deployed to Afghanistan as part of Operation Enduring Freedom in late 2001. The division headquarters arrived at Karshi-Khanabad Air Base, under Major General Franklin L. Hagenbeck, on 12 December 2001 to function as the Combined Forces Land Component Command (CFLCC) (Forward).[82] This command served as the representative for Lieutenant General Paul T. Mikolashek, the Third US Army/CFLCC commanding general (CG) in the theater of operations. As such, Hagenbeck's headquarters was responsible for commanding and controlling virtually all Coalition ground forces and ground force operations in the theater, including the security of Coalition airfields in Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, and Pakistan, as well as the logistics operations set up to support those forces. The division was also intended to defend Uzbekistan against attacks by the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, which was seeking to overthrow Islam Karimov's secular government.[83]

On 13 February 2002, Mikolashek ordered Hagenbeck to move CFLCC (Forward) to Bagram airfield located at Bagram and 2 days later the headquarters was officially redesignated as Combined Joint Task Force (CJTF) Mountain.[84] It assumed responsibility for the planning and execution of what had then become known as Operation Anaconda.[citation needed]

Elements of the division, primarily 1-87th Infantry, remained in the country until mid-2002, fighting to secure remote areas of the country and participating in prominent operations such as Operation Anaconda, the Fall of Mazar-i-Sharif, and the Battle of Qala-i-Jangi.[32] These 1-87th Infantry soldiers became the first US conventional forces to fight in Afghanistan. The division also participated in fighting in the Shahi Khot Valley in 2002. In June 2002, elements of the 82nd Airborne Division arrived to relieve CJTF Mountain, and in September, Major General John R. Vines and his Combined Task Force 82 relieved CJTF Mountain as the major subordinate headquarters to Combined Joint Task Force 180.[85] Upon the return of the battalions, they were welcomed home and praised by President Bush.[86]

In 2003, the division's headquarters, along with the 1st Brigade, returned to Afghanistan. During that time, they operated in the frontier regions of the country such as Paktika Province, going to places previously untouched by the war in search of Taliban and Al-Qaeda forces. Fighting in several small-scale conflicts such as Operation Avalanche, Operation Mountain Resolve, and Operation Mountain Viper, the division maintained a strategy of small units moving through remote regions of the country to interact directly with the population and drive out insurgents.[87] The 1st Brigade also undertook a number of humanitarian missions.[76]

In 2003 and into 2004, the division's aviation brigade deployed for the first time to Afghanistan. As the only aviation brigade in the theater, the brigade provided air support for all US Army units operating in the country. The brigade's mission at that time focused on close air support, medevac missions, and other duties involving combat with Taliban and Al-Qaeda forces in the country. The 10th Mountain Division was the first unit to introduce contract working dogs into southern Afghanistan. In the spring of 2004, they had Patriot K-9 Services supply 20 dog teams based at KAF. The teams were trained to detect explosives and perform patrol duties throughout the region. The brigade returned to Fort Drum in 2004.[88]

On the return of the division headquarters and 1st Brigade, the 10th Mountain Division began the process of transformation into a modular division.[89] On 16 September 2004, the division headquarters finished its transformation, adding the 10th Mountain Division Special Troops Battalion. The 1st Brigade became the 1st Brigade Combat Team,[90] while the 3rd Brigade Combat Team, 10th Mountain Division was activated for the first time.[91] In January 2005, the 4th Brigade Combat Team, 10th Mountain Division was activated at Fort Polk, Louisiana.[92] 2nd Brigade Combat Team would not be transformed until September 2005, pending a deployment to Iraq.[51]

Iraq deployments

[edit]In late 2004, the 2nd Brigade Combat Team was deployed to Iraq supporting Operation Iraqi Freedom. The 2nd Brigade Combat Team undertook combat operations in western Baghdad, an area of responsibility that included Abu Ghraib, Mansour, and Route Irish. It returned to the US in late 2005.[51] Around that time, the 1st Brigade Combat Team deployed back to Iraq, staying in the country until 2006.[90]

The next time the 1st Brigade Combat Team was deployed was during the Surge for 15 months in Iraq. Northern Iraq was the theater of operations for 1 BCT from August 2007 until November 2008.[citation needed]

The 4th BCT operated in Northeast Baghdad under the 4th Infantry Division headquarters from November 2007 until January 2009. The 10th Mountain participated in larger-scale operations, such as Operation Phantom Phoenix.[citation needed]

After a one-year rest, the headquarters of the 10th Mountain Division was deployed to Iraq for the first time in April 2008. The division headquarters served as the command element for southern Baghdad until late March 2009, when it displaced to Basrah to replace departing British forces on 31 March 2009 to coordinate security for the Multinational Division-South area of responsibility, a consolidation of the previously Polish-led south-central and British-led southeast operational areas. The 10th Mountain Division headquarters transferred authority for MND-S to the 34th Infantry Division, Minnesota Army National Guard on 20 May 2009.[citation needed]

The 2nd Brigade Combat Team was scheduled to deploy to Iraq in the fall of 2009, as a part of the 2009–2010 rotation to Iraq.[93]

Afghanistan deployments

[edit]

The division headquarters, the 3rd Brigade Combat Team, and two Battalion Task Forces from the 4th Brigade Combat Team deployed to Afghanistan in 2005, staying in the country until 2006. The division and brigade served in the eastern region of the country, along the border with Pakistan, fulfilling a similar role as it did during its previous deployment.[94] During this time, the deployment of the brigade was extended along with that of the 4th Brigade, 82nd Airborne Division. It was eventually replaced by the 173rd Airborne Brigade Combat Team which was rerouted from Iraq.[95]

In the winter of 2006, the 10th Aviation Brigade, 10th Mountain Division, was deployed again to Afghanistan to support Operation Enduring Freedom as the only aviation brigade in the theater, stationed at Bagram Air Base, Afghanistan. Named "Task Force Falcon," the brigade's mission was to conduct aviation operations to destroy insurgents and anti-coalition militia in an effort to help build the Afghan National Security Force's capability and allow the Afghan government to increase its capabilities. In addition, the Task Force provided logistical and combat support for International Security Assistance Force forces throughout the country.[96]

The 3rd Brigade Combat Team was slated to deploy to Iraq in 2009, but that deployment was rerouted. In January 2009, the 3rd BCT instead deployed to Kunar, Logar and Wardak Provinces, eastern Afghanistan to relieve the 101st Airborne Division, as part of a new buildup of US forces in that country.[97] The brigade was responsible for expanding forward operating bases and combat outposts (COPs) in the region, as well as strengthening US military presence in preparation for additional US forces to arrive.[98]

The 1st Brigade Combat Team was scheduled to deploy to Iraq in late 2009 but deployed instead to Afghanistan in March 2010 for 13 months.[99] 1-87th Infantry deployed to Kunduz and Baghlan Provinces, establishing remote combat outposts (COPs) against the Taliban after they had taken control of these provinces over the last several years. Notably, elements of the regiment were responsible for numerous large-scale engagements, including The Battle of Shahabuddin[100] and securing a High-Value Target (HVT) after an air assault raid. Some elements of the Brigade deployed to Afghanistan in late January 2013 to Ghazni Provence for nine months.[citation needed]

The 3rd Brigade Combat Team deployed to Kandahar Province, southern Afghanistan in March 2011, again relieving the 101st Airborne Division. During this deployment, 3rd BCT mainly occupied forward operating bases (FOBs) and combat outposts (COPs) in the Maywand, Zhari, and Arghandab Districts of Kandahar Province. The brigade was redeployed to Fort Drum in March 2012 after a twelve-month deployment.[citation needed]

The 4th Brigade Combat Team deployed to Regional Command East, under the 101st Airborne Division from October 2010 until their redeployment in October 2011. The 4th BCT deployed to both Wardak and Logar provinces. During this deployment, they went to places such as Chakh Valley in Wardak Province and Charkh Valley in Logar Province in search of elements of the Haqqani Network. In May 2013, the brigade deployed again to Afghanistan returning home in February 2014.[101]

In 2015, Diana M. Holland became the first woman to serve as a general officer at Fort Drum, and the first woman to serve as a deputy commanding general in one of the Army's light infantry divisions (specifically, the 10th Mountain Division.)[102]

In February 2015, 2nd Brigade Combat Team, 10th Mountain Division were deployed to Afghanistan as part of the Resolute Support Mission in the Post ISAF phase of the War in Afghanistan[103] between late summer and early fall 2015, 300 troops from 10th Mountain's headquarters at deployed to Afghanistan in support of Operation Freedom's Sentinel, along with about 1,000 troops from the 3rd Brigade Combat Team.[104] In February 2016, the Taliban began a new assault on Sangin, Helmand Province, the US responded by deploying 500 to 800 troops from 2nd battalion 87th Infantry Regiment, 10th Mountain Division to Helmand Province in order to prop up Afghan army's 215th Corps in the province, particularly around Sangin, joining US and British special operations forces already in the area.[105][106][107]

On 5 December 2019, the Department of the Army announced that the 1st Brigade Combat Team would replace the 3rd Brigade Combat Team, 82nd Airborne Division as part of a unit rotation in support of Operation Freedom's Sentinel.[108] The brigade deployed to Afghanistan in February 2020.[citation needed]

Operation Atlantic Resolve

[edit]On 3 November 2016, Stars and Stripes reported that the 10th Combat Aviation Brigade would deploy 1,750 soldiers to Eastern Europe in March 2017, in support of Operation Atlantic Resolve – as part of NATO efforts to reassure Eastern Europe in response to Russian intervention in Ukraine in 2014. The brigade arrived with approximately 60 aircraft, including CH-47 Chinooks, UH-60 Blackhawks, and medevac helicopters. The brigade was headquartered in Germany and the brigade's units were forward-based at locations in Latvia, Romania, and Poland.[109]

Operation Inherent Resolve

[edit]Between late summer and early fall 2015, as well as again in 2016, 1,250 soldiers from the 1st Brigade Combat Team were deployed to Iraq to support Operation Inherent Resolve.[110] During the two deployments the brigade spent in Iraq, they fought to regain control of the cities of Ramadi, Fallujah, and Mosul from the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria.[111] In 2022 the unit would redeploy again, in support of Operation Inherent Resolve.[112]

Controversial shoot house training viral video

[edit]A viral video showed soldiers in the division conducting live fire training in a shoot house.[113][114][115] The soldiers violated numerous safety issues, including flagging and failure to follow norms of room clearing, such as failure to clear corners or follow points of domination, with observers giving no correction.[113][114][115] Responding to the viral incident, Division CSM Mario O. Terenas addressed the incident on Twitter: "it's 10th Mountain Division. We ran it down to the ground and it is 10th Mountain Division. It is our folks, and it really, really hurts to say that...It is not the standard, it is not how we do business, and it is not acceptable. We're running this thing down to the ground. We will investigate it, we will take action, and we will re-train. That is a guarantee."[116]

Honors

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2024) |

The 10th Mountain Division was awarded two campaign streamers in World War II, one campaign streamer for Somalia, and four campaign streamers in the War on Terrorism for a total of seven campaign streamers and three unit decorations in its operational history. Note that some of the division's brigades received more or fewer decorations depending on their individual deployments.[32]

Unit decorations

[edit]| Ribbon | Award | Year | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Meritorious Unit Commendation (Army) | 2001–2002 | for service in Central Asia | |

| Meritorious Unit Commendation (Army) | 2003–2004 | for service in Afghanistan | |

| Meritorious Unit Commendation (Army) | 28 Feb 06 – 27 Feb 07 | for service in Afghanistan[117] | |

| Valorous Unit Award (Army) | Aug 2006 - Oct 2007 | For outstanding service in Iraq | |

| Meritorious Unit Commendation (Army) | 2008–2009 | for service in Iraq[118] | |

| Meritorious Unit Commendation (Army) | 2014 | for service in Afghanistan | |

| Joint Meritorious Unit Award (Army) | 1992–1995 | for service in Somalia |

Campaign streamers

[edit]| Conflict | Streamer | Year(s) |

|---|---|---|

| World War II | North Apennines | 1945 |

| World War II | Po Valley | 1945 |

| Operation Restore Hope | Somalia | 1992–1994 |

| Operation Enduring Freedom | Afghanistan | 2001–2002 |

| Operation Enduring Freedom | Afghanistan | 2003–2004 |

| Operation Enduring Freedom | Afghanistan | 2006–2007 |

| Operation Iraqi Freedom | Iraq | 2008–2009 |

| Operation Enduring Freedom | Afghanistan | 2010–2011 |

Legacy

[edit]Skiing associations subsequently contend that veterans of the 10th Mountain Division had a substantial effect on the post-World War II development of skiing as a vacation industry and major sport. Ex-soldiers from the 10th laid out ski hills, designed ski lifts, became ski coaches, racers, instructors, patrollers, shop owners, and filmmakers. They wrote and published ski magazines, opened ski schools, improved ski equipment, and developed ski resorts. Up to 2,000 of the division's troops were involved in skiing-related professions after the war, and at least 60 ski resorts were founded by men of the division.[119] As Maurice Isserman notes in his book The Winter Army, "The 10th Mountain Division was the only unit in the history of the US military to use wartime skills to promote a civilian pastime."[120]

People associated with the 10th Mountain Division later went on to achieve notability in other fields. Among these are anthropologist Eric Wolf,[121] mathematician Franz Alt,[122] avalanche researcher and forecasting pioneer Montgomery Atwater,[123] Congressman Les AuCoin, mountaineer and teacher who helped develop equipment for the 10th Mountain Robert Bates, noted mountaineer Fred Beckey,[124] United States Ski Team member and Black Mountain of Maine resort co-founder Chummy Broomhall,[125] former American track and field coach and co-founder of Nike, Inc. Bill Bowerman,[126] former executive director and Sierra Club leader David R. Brower,[127] former United States Ski Team member World War II civilian mountaineer trainer H. Adams Carter, former Senate Majority Leader and Presidential candidate Bob Dole,[128] champion skier Dick Durrance, ski resort pioneer John Elvrum,[129] Norwegian-American skier Sverre Engen, fashion illustrator Joe Eula, Olympic equestrian Earl Foster Thomson, civilian founder of the National Ski Patrol Charles Minot Dole,[77] painter Gino Hollander, Paleoclimatologist John Imbrie,[130] theoretical physicist Francis E. Low,[131] US downhill ski champion Toni Matt,[132] falconer and educator Morley Nelson, comic book artist Earl Norem,[133] founder of National Outdoor Leadership School and The Wilderness Education Association Paul Petzoldt, world downhill ski champion Walter Prager, demolition derby driver Joshua Tagliaboschi, retired broadcasting executive William Lowell Putnam III, Massachusetts Governor Francis W. Sargent, World War II civilian ski instructor and division trainer Hannes Schneider, founder of Vail Ski Resort Pete Seibert, actor and Olympic medalist Floyd Simmons, historian and author Page Smith,[134] members of the famous von Trapp family singers Werner von Trapp and Rupert von Trapp,[135] Rawleigh Warner, Jr., chairman and CEO of Mobil, civilian technical adviser Fritz Wiessner,[136] William John Wolfgram,[137] Olympic Ski jumper Gordon Wren, Massachusetts Congressional candidate Nathan Bech,[138] leader of Chalk 4 during the Battle of Mogadishu Matt Eversmann,[139] Middle East analyst, blogger, and author Andrew Exum, and author Craig Mullaney.[140]

Additionally, four members of the division have been awarded the Medal of Honor. In 1945 John D. Magrath became the first member of the division to receive this award (posthumously) during World War II.[141][142] The second, Jared C. Monti, received it posthumously in 2009, for actions during a combat operation on 21 June 2006 as part of Operation Enduring Freedom.[143] The third, William D. Swenson, received it in 2013, for actions on 8 September 2009, during the Battle of Ganjgal in Afghanistan.[144] The fourth, Travis W. Atkins, received it posthumously on 27 March 2019, for actions on 1 June 2007 during a patrol in Iraq.[145]

The division's efforts in Afghanistan during Operation Enduring Freedom and beyond led to the division being referred to as the "Tribe of Crossed Swords" by some Afghans.[146]

In popular culture

[edit]The 10th Mountain Division was the subject of the 1996 film Fire on the Mountain, which documented its exploits during World War II. The 10th Mountain Division is also a prominent element of the book Black Hawk Down and film by the same name, which portrays the Battle of Mogadishu and the division's participation in that conflict.[147] Among the division's other appearances are the Tom Clancy novel Clear and Present Danger,[148] the 2004, War Of The Worlds remake, the 2005 SCI FI film Manticore,[149] 2010 remake starring Keanu Reeves, The Day The Earth Stood Still, Sean Parnell's 2012 war memoir, Outlaw Platoon, about his platoon's experiences in Afghanistan during Operation Enduring Freedom,[150] the 2019 action adventure video game Days Gone, with the game's main protagonist, Deacon St. John, referencing his time spent with the 10th Mountain Division in Afghanistan.

Organization

[edit]

This division consists of a division headquarters and headquarters battalion, three infantry brigade combat teams, a division artillery, a combat aviation brigade, and a division sustainment brigade. The division artillery has training and readiness oversight over the division's field artillery battalions, which remain organic to their brigade combat teams.[citation needed]

10th Mountain Division

10th Mountain Division

Division Headquarters and Headquarters Battalion (DHHB)"Gauntlet"

Division Headquarters and Headquarters Battalion (DHHB)"Gauntlet"

- Headquarters Support Company[151]

- Signal, Intelligence, and Sustainment Company

- 10th Mountain Division Band

- Light Fighters School

- 1st Infantry Brigade Combat Team (1st IBCT) "Warrior"[152]

Headquarters and Headquarters Company (HHC), 1st Infantry Brigade Combat Team (1st IBCT)

Headquarters and Headquarters Company (HHC), 1st Infantry Brigade Combat Team (1st IBCT) 3rd Squadron, 71st Cavalry Regiment * Deactivated June 5, 2024[153]

3rd Squadron, 71st Cavalry Regiment * Deactivated June 5, 2024[153]2nd Battalion, 22nd Infantry Regiment

1st Battalion, 32nd Infantry Regiment

1st Battalion, 32nd Infantry Regiment 1st Battalion, 87th Infantry Regiment

1st Battalion, 87th Infantry Regiment 3rd Battalion, 6th Field Artillery Regiment (3-6th FAR)

3rd Battalion, 6th Field Artillery Regiment (3-6th FAR) 7th Brigade Engineer Battalion (7th BEB)

7th Brigade Engineer Battalion (7th BEB) 10th Brigade Support Battalion (10th BSB)

10th Brigade Support Battalion (10th BSB)

- 2nd Infantry Brigade Combat Team (2nd IBCT) "Commandos"[152][154]

Headquarters and Headquarters Company (HHC), 2nd Infantry Brigade Combat Team (2nd IBCT)

Headquarters and Headquarters Company (HHC), 2nd Infantry Brigade Combat Team (2nd IBCT) 1st Squadron, 89th Cavalry Regiment * Deactivated June 7, 2024[155]

1st Squadron, 89th Cavalry Regiment * Deactivated June 7, 2024[155] 2nd Battalion, 14th Infantry Regiment

2nd Battalion, 14th Infantry Regiment 4th Battalion, 31st Infantry Regiment

4th Battalion, 31st Infantry Regiment 2nd Battalion, 87th Infantry Regiment

2nd Battalion, 87th Infantry Regiment 2nd Battalion, 15th Field Artillery Regiment (2-15th FAR)

2nd Battalion, 15th Field Artillery Regiment (2-15th FAR) 41st Brigade Engineer Battalion (41st BEB)

41st Brigade Engineer Battalion (41st BEB) 210th Brigade Support Battalion (210th BSB)

210th Brigade Support Battalion (210th BSB)

- 3rd Infantry Brigade Combat Team (3rd IBCT) "Patriots", based at Fort Johnson, (Louisiana)[156][157]

Headquarters and Headquarters Company (HHC), 3rd Infantry Brigade Combat Team (3rd IBCT)

Headquarters and Headquarters Company (HHC), 3rd Infantry Brigade Combat Team (3rd IBCT) 3rd Squadron, 89th Cavalry Regiment * Deactivated June 28, 2024[158]

3rd Squadron, 89th Cavalry Regiment * Deactivated June 28, 2024[158] 2nd Battalion, 2nd Infantry Regiment

2nd Battalion, 2nd Infantry Regiment 2nd Battalion, 4th Infantry Regiment

2nd Battalion, 4th Infantry Regiment 2nd Battalion, 30th Infantry Regiment

2nd Battalion, 30th Infantry Regiment 5th Battalion, 25th Field Artillery Regiment (5-25th FAR)

5th Battalion, 25th Field Artillery Regiment (5-25th FAR) 317th Brigade Engineer Battalion (317th BEB) "Buffalo"

317th Brigade Engineer Battalion (317th BEB) "Buffalo" 710th Brigade Support Battalion (710th BSB) "Patriot Support"

710th Brigade Support Battalion (710th BSB) "Patriot Support"

- 10th Division Artillery (10th DIVARTY)

- 10th Combat Aviation Brigade (10th CAB) "Falcons"[156]

Headquarters and Headquarters Company (HHC), 10th Combat Aviation Brigade (10th CAB)

Headquarters and Headquarters Company (HHC), 10th Combat Aviation Brigade (10th CAB) 6th Squadron (Attack/ Reconnaissance), 6th Cavalry Regiment "Six Shooters"

6th Squadron (Attack/ Reconnaissance), 6th Cavalry Regiment "Six Shooters" 1st Battalion (Attack), 10th Aviation Regiment "Tigershark"

1st Battalion (Attack), 10th Aviation Regiment "Tigershark" 2nd Battalion (Assault), 10th Aviation Regiment

2nd Battalion (Assault), 10th Aviation Regiment 3rd Battalion (General Support), 10th Aviation Regiment "Phoenix"

3rd Battalion (General Support), 10th Aviation Regiment "Phoenix" 277th Aviation Support Battalion (277th ASB) "Mountain Eagle"

277th Aviation Support Battalion (277th ASB) "Mountain Eagle"

- 10th Division Sustainment Brigade[159]

Headquarters and Headquarters Company (HHC)

Headquarters and Headquarters Company (HHC) Division Sustainment Troops Battalion (DSTB) "Workhorse"[160]

Division Sustainment Troops Battalion (DSTB) "Workhorse"[160] 548th Division Sustainment Support Battalion (548th DSSB)

548th Division Sustainment Support Battalion (548th DSSB)

Previous commanders

[edit]Individuals who have served as commanders and command sergeants major of the 10th Mountain Division include:[161]

|

Division commanders

|

Division commanders (continued)

|

Command Sergeants Major

|

Notable former members

[edit]- Travis Atkins, Iraq[162]

- Skippy Baxter, World War II[163]

- Bill Bowerman, World War II[164]

- David Brower, World War II[164]

- Bob Dole, World War II[165]

- Donald G. Dunn, World War II[166]

- Billy Kearns, World War II[167]

- John David Magrath, World War II[168]

- Chelsea Manning, Iraq[169]

- Jared C. Monti, Afghanistan[170]

- Paul Petzoldt, World War II[164]

- Walter Prager, World War II[164]

- Michael Prysner, Iraq[171]

- Pete Seibert, World War II[164]

- William D. Swenson, Afghanistan[172]

- Torger Tokle, World War II

- Rupert von Trapp, World War II[165]

- Werner von Trapp, World War II[165]

- Alejandro Villanueva, Afghanistan[165]

- Eric Wolf, World War II

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "10th Mountain Division: Shoulder Sleeve Insignia". The Institute of Heraldry. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2015.

- ^ a b Skely, Patrick G. "5th Army History • Conclusion". Archived from the original on 13 April 2017. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ^ "Today's 10th Moun/tain Division". 10th Mountain Division Info.

- ^ McGrath 2004, p. 166

- ^ Pushies 2008, p. 7

- ^ Shelton 2003, pp. 8–9

- ^ Shelton 2003, p. 10

- ^ Look magazine page 4, 25 March 1941

- ^ a b Baumgardner 1998, p. 15

- ^ Shelton 2003, p. 13

- ^ Shelton 2003, p. 15

- ^ Shelton 2003, pp. 24–25

- ^ Skiing Heritage Journal 1995, p. 8

- ^ a b c Baumgardner 1998, p. 16

- ^ Pushies 2008, p. 10

- ^ Skiing Heritage Journal 1995, p. 5

- ^ Baumgardner 1998, p. 17

- ^ Baumgardner 1998, p. 18

- ^ Shelton 2003, p. 34

- ^ Pushies 2008, p. 8

- ^ Pushies 2008, p. 11

- ^ a b Baumgardner 1998, p. 20

- ^ Feuer 2006, p. iv

- ^ Govan, Thomas P. (1 September 1946). "History of the tenth Light Division (Alpine): The Army Ground Forces Study No. 28". history.army.mil. Washington, DC: U.S. Army ground Forces. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ Baumgardner 1998, p. 19

- ^ a b c Young 1959, p. 592

- ^ Feuer 2006, p. vi

- ^ Pushies 2008, p. 12

- ^ Pushies 2008, p. 6

- ^ Shelton 2003, p. 2

- ^ Baumgardner 1998, p. 25

- ^ a b c "Lineage and Honors Information: 10th Mountain Division". United States Army Center of Military History. Archived from the original on 8 June 2010. Retrieved 6 July 2009.

- ^ "Biography of Lieutenant-General George Price Hays (1892 – 1978), USA". generals.dk.

- ^ a b Feuer 2006, p. vii

- ^ a b c d Young 1959, p. 590

- ^ Skiing Heritage Journal 1995, p. 6

- ^ McKay Jenkins, The Last Ridge (New York: Random House, 2003), p. 149 ISBN 0-375-50771-X

- ^ Baumgardner 1998, p. 26 to 32

- ^ a b c Feuer 2006, p. viii

- ^ a b c d e f Young 1959, p. 591

- ^ https://apnews.com/general-news-c9909482ce6443a585fa3c83db41aac7

- ^ https://www.uswarmemorials.org/html/monument_details.php?SiteID=1408&MemID=2001

- ^ Feuer 2006, p. ix

- ^ a b c d e Army Battle Casualties and Nonbattle Deaths, Final Report (Statistical and Accounting Branch, Office of the Adjutant General, 1 June 1953)

- ^ Baumgardner 1998, p. 39

- ^ Feuer 2006, p. x

- ^ Baumgardner 1998, p. 37

- ^ a b c d e f g Baumgardner 1998, p. 40

- ^ McGrath 2004, p. 189

- ^ McGrath 2004, p. 232

- ^ a b c d Sasser 2009, p. 12

- ^ Johnson & Callahan 2012, p. 13.

- ^ Hensler, Robert. "Activation of 1-22 IN at Ft. Drum, NY in the 10th Mountain Division". 1st Battalion 22nd Infantry. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- ^ "Lake View Native Earns High Military Post". The Sun and the Erie County Independent. 8 June 1989. p. 15 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "I-87 Battalion History". 1st Brigade Combat Team, 10th Mountain Division. Archived from the original on 1 November 2011. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- ^ a b c d Pushies 2008

- ^ "2nd Battalion, 14th Infantry Lineage". US Army Center of Military History. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ^ "2nd Battalion, 87th Infantry Lineage". US Army Center of Military History. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ^ "27th Infantry Brigade (Light)". Global Security. Retrieved 2 July 2020. [unreliable source?]

- ^ a b c "108th Infantry Lineage". US Army Center of Military History. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ^ McKenney, Janice E. "Field Artillery – Army Lineage Series – Part 2" (PDF). US Army Center of Military History. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ^ "Headquarters and Headquarters Company, Combat Aviation Brigade, 10th Mountain Division | Lineage and Honors | U.S. Army Center of Military History". history.army.mil.

- ^ "3rd Squadron, 17th Cavalry Lineage". US Army Center of Military History. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ^ "2nd Battalion, 25th Aviation Lineage". US Army Center of Military History. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ^ "3rd Battalion, 25th Aviation Lineage". US Army Center of Military History. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ^ "Field Artillery – February 1990". US Army Field Artillery School. 1990. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ "Field Artillery – February 1987". US Army Field Artillery School. 1987. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- ^ "1st Battalion, 7th Field Artillery Lineage". US Army Center of Military History. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ^ a b c McKenney, Janice E. "Field Artillery – Army Lineage Series – Part 1" (PDF). US Army Center of Military History. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ^ "10th Support Battalion Lineage". US Army Center of Military History. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ^ "41st Engineer Battalion Lineage". US Army Center of Military History. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ^ Raines, Rebecca Robbins. "Signal Corps" (PDF). US Army Center of Military History. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- ^ "59th Chemical Company Lineage". US Army Center of Military History. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ^ "10th Mountain Division Band Lineage". US Army Center of Military History. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ^ a b c d Skiing Heritage Journal 1995, p. 13

- ^ a b c d "GlobalSecurity.org: 10th Mountain Division". GlobalSecurity. Retrieved 6 July 2009.

- ^ a b c d e "Fort Drum Homepage: History of the 10th Mountain Division". Fort Drum Public Affairs Office. Archived from the original on 12 May 2008. Retrieved 6 July 2009.

- ^ a b "Army Strikes Back at Bush". ABC News. Retrieved 9 July 2009.

- ^ a b "The Facts about Military Readiness". The Heritage Foundation. Archived from the original on 31 January 2010. Retrieved 9 July 2009.

- ^ "Army: 2 Units Unprepared". CBS News. 10 November 1999. Archived from the original on 5 February 2011. Retrieved 9 July 2009.

- ^ "No Bad Units, Only Bad Leaders". David Hackworth. Archived from the original on 11 June 2009. Retrieved 9 July 2009.

- ^ A Different Kind of War, 127.

- ^ Henriksen, Thomas H. (31 January 2022). America's Wars: Interventions, Regime Change, and Insurgencies after the Cold War (1 ed.). Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781009053242.005. ISBN 978-1-009-05324-2.

- ^ A Different Kind of War, 132

- ^ Koontz, Enduring Voices, 3.

- ^ Gilmore, Gerry (19 July 2002). "'Be Proud, Strong, Ready,' Bush Tells 10th Mountain Troops". US Department of Defence. American Forces Press Service. Archived from the original on 28 September 2015. Retrieved 18 December 2015.

- ^ "Going in small in Afghanistan". The Christian Science Monitor. 14 January 2004. Retrieved 9 July 2009.

- ^ "10th Combat Aviation Brigade Assumes OEF Aviation Mission". Defenselink.mil. Retrieved 19 July 2009.

- ^ "FORT DRUM PAMPHLET 600 – 5" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 August 2017. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- ^ a b "Lineage and Honors Information: 1st Brigade Combat Team, 10th Mountain Division". United States Army Center of Military History. Archived from the original on 16 January 2010. Retrieved 9 July 2009.

- ^ "Lineage and Honors Information: 3rd Brigade Combat Team, 10th Mountain Division". United States Army Center of Military History. Archived from the original on 8 June 2010. Retrieved 9 July 2009.

- ^ "Lineage and Honors Information: 4th Brigade Combat Team, 10th Mountain Division". United States Army Center of Military History. Archived from the original on 8 June 2010. Retrieved 9 July 2009.

- ^ "Army Announces next Iraq Rotation". US Army Public Affairs Office. Retrieved 15 July 2009.

- ^ Sasser 2009, p. 1

- ^ Vogt, Melissa (16 February 2007). "173rd Airborne heading to Afghanistan". Army Times. Archived from the original on 8 December 2012. Retrieved 24 April 2008.

- ^ "GlobalSecurity.org: 10th Combat Aviation Brigade". GlobalSecurity. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ^ "10th Mountain Division Leads New Deployments to Afghanistan". DefenseLink. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- ^ "10th Mountain Division troops move into Logar, Wardak provinces". ISAF Public Affairs Office. Archived from the original on 16 July 2009. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- ^ Garamone, Jim (10 December 2009). "1st Brigade Combat Team will join troop surge in Afghanistan". Fort Drum: United States Army. American Forces Press Service. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2015.

- ^ Demmer, Ulrike (13 October 2010). "The Battle of Shahabuddin". Spiegel Online. Retrieved 13 October 2010.

- ^ Matthews, Jeff (12 February 2014). "Local News | The Town Talk". thetowntalk.com. Archived from the original on 15 February 2014. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- ^ "Fort Drum marks promotion of first woman general of 10th Mountain Division". syracuse.com. 30 July 2015. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ^ Gary Walts (26 February 2015). "Fort Drum brigade prepares for deployment to Afghanistan". The Post-Standard. Syracuse Media Group. Associated Press. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

Tan, Michelle (27 February 2015). "Army announces new Afghanistan deployments". ArmyTimes. Gannett. Retrieved 28 February 2015. - ^ "Army names 3 units for Iraq, Afghanistan deployments". 5 August 2015.

- ^ "US Army orders hundreds of soldiers back to southern Afghanistan". Fox News. 11 February 2016.

- ^ "SAS in battle to stop Taliban overrunning Sangin". The Telegraph. 22 December 2015. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

- ^ "A 5th District in Helmand Province Falls to the Taliban". The New York Times. 15 March 2016.

- ^ "1st BCT, 10th Mountain Division to replace 3rd BCT, 82nd Airborne Division for unit rotation in the winter of 2020". army.mil. 5 December 2019. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ^ "2 brigades of nearly 6,000 troops head to Europe amid growing Russian tensions". stars and stripes. 3 November 2016.

- ^ "Troops from Fort Drum's 10th Mountain Division to deploy to Iraq, Afghanistan". New York Daily News. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- ^ "10th Mountain Division (LI) :: Fort Drum". home.army.mil. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ^ "Army announces upcoming 1st IBCT, 10th Mountain Division unit deployment". www.army.mil. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ^ a b Rempfer, Kyle (24 February 2021). "Shoot-house video is full of 'flagging'; 10th Mountain senior enlisted vows problems will 'get fixed'". Army Times. Retrieved 3 December 2022.

- ^ a b "This video of 10th Mountain soldiers shows exactly what not to do when clearing a room". Task & Purpose. 23 February 2021. Retrieved 3 December 2022.

- ^ a b Hollings, Alex. "How a 'shoot house' training video became a headache for one of the Army's most highly regarded units". Business Insider. Retrieved 3 December 2022.

- ^ @mtn7_csm (22 February 2021). "I want to address the recent shoot-house video..." (Tweet). Retrieved 4 March 2023 – via Twitter.

- ^ "Army General Orders Unit Award Index 1987 to present". Archived from the original on 12 October 2018. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ^ "War on Terrorism Awards". United States Army Center of Military History. Archived from the original on 5 December 2009. Retrieved 30 July 2009.

- ^ Skiing Heritage Journal 1995, p. 3

- ^ Isserman, The Winter Army (New York: HarperCollins, 2019), p. 240 ISBN 978-0-358-41424-7

- ^ Ghani, Ashraf; Eric Wolf (May 1987). "A conversation with Eric Wolf". American Ethnologist. 14 (2): 346–66. doi:10.1525/ae.1987.14.2.02a00110. ISSN 0094-0496.

- ^ Beyond Calculation: The Next Fifty Years of Computing (Springer, 1998). ISBN 978-0-387-98588-6

- ^ Brennan, John (2006). "Genesis of the Avalauncher" (PDF). The Avalanche Review. 24 (3). American Avalanche Association: 18–19. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 August 2008.

- ^ Modie, Neil (8 March 2003). "Icon to some, legendary climber Beckey still obscure to many". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved 7 January 2006.

- ^ Burke, Heather (16 December 2001). "Remembering The 10th – A Look Back at Ski Warriors". Maine Sunday Telegram. Archived from the original on 25 June 2007. Retrieved 12 May 2007.

- ^ Moore, Kenny (2006). Bowerman and the Men of Oregon. Emmaus, Pennsylvania: Rodale. ISBN 978-1-59486-190-1.

- ^ Steve Roper, "David Ross Brower", American Alpine Journal, 2001, p. 455.

- ^ "Losing the War – by Lee Sandlin". leesandlin.com.

- ^ "John Elvrum". U.S. Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame and Museum. Retrieved 15 March 2012.

- ^ Yale Science and Engineering Alumni Hall of Achievement web page. Retrieved 9 April 2008 Archived 18 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Physicist Francis E. Low, Former MIT Provost, Dies at 85". MIT News Office. 20 February 2007. Retrieved 10 March 2007.

- ^ Toni Matt Dies at 69; Former Ski Champion, The New York Times, 19 May 1989. Retrieved 2 December 2007.

- ^ Yzquierdo, Ryan. "Earl Norem and the Big Looker Storybooks", Seibertron.com (2 December 2005).. Retrieved 21 August 2008.

- ^ Martin, Douglas (28 July 2002). "Pete Seibert, Soldier Skier Who Built Vail, Is Dead at 77". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 December 2015.

- ^ "Werner von Trapp, a Son in 'Sound of Music' Family, Dies at 91". The New York Times. Associated Press. 15 October 2007. Retrieved 5 January 2009.

- ^ Schwartz, Susan (2005) Into The Unknown: The Remarkable Life of Hans Kraus

- ^ "William Wolfgram". Widener University. Archived from the original on 8 February 2007. Retrieved 30 November 2007.

- ^ "Bech challenges Olver". Archived from the original on 20 May 2011. Retrieved 6 July 2008.

- ^ Bowden, M (1999). Black Hawk Down, Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-451-20393-9

- ^ "Biography of Craig Mullaney". Craig Mullaney. Archived from the original on 17 March 2014. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- ^ "Medal of Honor Recipients — Vietnam (A-L)". United States Army. Archived from the original on 27 May 2009. Retrieved 24 April 2008.

- ^ "Medal of Honor Recipients — Vietnam (M-Z)". United States Army. Archived from the original on 24 April 2008. Retrieved 24 April 2008.

- ^ Cavallaro, Gina (23 July 2009). "Fallen soldier to receive Medal of Honor". Army Times. Archived from the original on 6 August 2009. Retrieved 23 July 2009.

- ^ Clark, Lesley (16 September 2013). "After long wait, Seattle man gets highest military honor". The Seattle Times. Retrieved 17 September 2013.

- ^ Higgins, Grady (12 March 2019). "Montanan Travis Atkins to posthumously receive Medal of Honor at White House". Great Falls Tribune. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- ^ "10th Mountain Division sister brigades complete decade of service: Spartans, Patriots combine". 27 February 2015. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ^ Bowden, Mark (March 1999). Black Hawk Down: A Story of Modern War. Atlantic Monthly Press. Berkeley, California. ISBN 978-0-87113-738-8

- ^ Clancy, Tom (1989). Clear and Present Danger. Putnam. ISBN 978-0-399-13440-1.

- ^ Buchanan, Jason (2007). "Manticore (2005)". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 13 December 2007. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- ^ Michelle Kennedy (1 March 2012). "Outlaw: Former infantry officer shares experiences, pledges to help others". U.S. Army. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- ^ "10th Mountain Soldier trains at the Chilean Mountain Warfare School". www.army.mil.

- ^ a b "10th Mountain Division Organization". Fort Drum Public Affairs Office. Archived from the original on 1 August 2008. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- ^ 3-71 Cavalry Regiment Photos (Image 4 of 4), Defense Visual Information Distribution Service, by SPC Mason Nichols (27th Public Affairs Detachment), dated 6 June 2024, last accessed 22 July 2024

- ^ "Special Unit Designations". United States Army Center of Military History. 21 April 2010. Archived from the original on 12 May 2009. Retrieved 23 June 2010.

- ^ The Squadron will inactivate on 07JUN24 at 1300 at Memorial Field, 1st Squadron, 89th Cavalry Regiment Facebook page, post dated 8 May 2024, last accessed 22 July 2024

- ^ a b "Fort Polk gains 700 soldiers as Army's 4th Brigade is redesignated".

- ^ Matthews, Jeff. "Fort Polk brigade takes new name". The Town Talk.

- ^ 3rd Squadron 89th Cavalry Regiment Facebook page, last accessed 22 July 2024

- ^ "Error". Archived from the original on 10 June 2011. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ^ "Special Troops Battalion, 10th Mountain Division". The Institute of Heraldry. Retrieved 21 February 2024.

- ^ MacDonald, Thomas D.; Kobylanski, Lori J. (20 April 2015). Fort Drum Pamphlet 600-5: 10th Mountain Division (Light Infantry) and Fort Drum Standards. Fort Drum, NY: 10th Mountain Division (Light Infantry). p. 31. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- ^ Strasser, Mike (27 March 2019). "Soldier recalls serving with Medal of Honor recipient Staff Sgt. Travis Atkins". Army.mil. Arlington, VA.

- ^ Smith, Chris (19 December 2012). "'Skippy' Baxter an inspiration on ice". The Press Democrat. Santa Rosa, CA.

- ^ a b c d e Leonard, Brendan (20 January 2015). "Famous 10th Mountain Division Veterans". Adventure Journal. Dana Point, CA.

- ^ a b c d Case, Mike (9 July 2021). "Skiing, Sen. Bob Dole and the Von Trapp Brothers: 10 Facts About the 10th Mountain Division". USO.org. Arlington, VA.

- ^ "In Memoriam: Donald G. Dunn (1923-2021)". Ohio State University Department of History News. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University. 18 August 2021.

- ^ "Bill Kearns, 69, Actor Seen in French Films". The New York Times. New York, NY. 4 December 1992. p. D-19.

- ^ DeWitt, Jeffrey (28 July 2020). "Private First Class John David McGrath; U.S. Army". Honor Norwalk, Connecticut veterans. Norwalk, CT.

- ^ Mcgraw, Meridith; Kelsey, Adam (16 May 2017). "Everything you need to know about Chelsea Manning". ABC News. New York, NY.

- ^ Cole, Jeff (26 May 2021). "Retired Fort Drum soldiers share their Afghanistan war experience". WWNY TV. Watertown, NY.

- ^ Blevins, Aaron (17 January 2013). "Activists' anti-war fight continues". Beverly Press. Beverly Hills, CA.

- ^ "President Obama to Award Medal of Honor". The White House, Office of the Press Secretary. Washington, DC. 16 September 2013.

Sources

[edit]- "Skiing Heritage Journal: The 10th Mountain Division's 50th Memorial Day", Skiing Heritage Journal, 7 (2), New Hartford, Connecticut, 1995, ISSN 1082-2895, OCLC 29404456

- Baumgardner, Randy W. (1998), 10th Mountain Division, Nashville, Tennessee: Turner Publishing Company, ISBN 978-1-56311-430-4

- Feuer, A.B. (2006), Packs On!: Memoirs of the 10th Mountain Division in World War II, Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books, ISBN 978-0-8117-3289-5

- Hampton, Henry J. (12 June 1945), The Riva Ridge Operation (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 13 June 2013, retrieved 30 January 2014

- Johnson, Andy; Callahan, Pat (2012). NATO Order of Battle 1989.

- McGrath, John J. (2004), The Brigade: A History: Its Organization and Employment in the US Army, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: Combat Studies Institute Press, ISBN 978-1-4404-4915-4

- Parnell, Sean (2012), Outlaw Platoon: heroes, renegades, infidels, and the brotherhood of war in Afghanistan, New York, NY: William Morrow, ISBN 978-0-06-206639-8 plus Author Webcast Interview

- Pushies, Fred (2008), 10th Mountain Division, Minneapolis, Minnesota: Zenith Press, ISBN 978-0-7603-3349-5

- Sasser, Charles W. (2009), None Left Behind: The 10th Mountain Division and the Triangle of Death, New York City, New York: St. Martin's Press, ISBN 978-0-312-55544-3

- Shelton, Peter (2003), Climb to Conquer: The Untold Story of WWII's 10th Mountain Division Ski Troops, New York City, New York: Scribner, ISBN 978-0-7432-2606-6

- Young, Gordon Russell (1959), Army Almanac: A Book of Facts Concerning the Army of the United States, Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, ISBN 978-0-7581-3548-3

Further reading

[edit]- Mountaineers (Denver: Artcraft Press, n.d.)

- Hal Burton, The Ski Troops (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1971)

- Harris Dusenbery, The North Apennines and Beyond with the 10th Mountain Division (Portland: Binford & Mort, 1998)

- Harris Duesenbery, Ski the High Trail: World War II Ski Troopers in the High Colorado Rockies (Portland:Binford & Mort, 1991)

- Frank Harper, Night Climb (New York: Longmans, Green, & Co, 1946)

- Maurice Isserman, The Winter Army: The World War II Odyssey of the 10th Mountain Division, America's Elite Alpine Warriors (New York: HarperCollins, 2019)

- McKay Jenkins, The Last Ridge (New York: Random House, 2003) ISBN 0-375-50771-X

External links

[edit]- 10th Mountain Division (United States)

- Infantry divisions of the United States Army in World War II

- Military units and formations established in 1943

- Military units and formations in New York (state)

- Mountain infantry divisions

- United States Army divisions during World War II

- United States Army divisions of World War I