Tyrannotitan

| Tyrannotitan Temporal range: Early Cretaceous (Aptian),

| |

|---|---|

| |

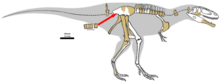

| Reconstructed skeleton in Queensland Museum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Family: | †Carcharodontosauridae |

| Tribe: | †Giganotosaurini |

| Genus: | †Tyrannotitan Novas et al., 2005 |

| Type species | |

| †Tyrannotitan chubutensis Novas et al., 2005

| |

Tyrannotitan (/tɪˌrænəˈtaɪtən/; lit. 'tyrant titan') is a genus of large bipedal carnivorous dinosaur of the carcharodontosaurid family from the Aptian stage of the early Cretaceous period, discovered in Argentina. It is closely related to other giant predators like Carcharodontosaurus and especially Giganotosaurus as well as Mapusaurus.

Discovery and species

[edit]

Tyrannotitan chubutensis was described by Fernando E. Novas, Silvina de Valais, Pat Vickers-Rich, and Tom Rich in 2005. The fossils were found at La Juanita Farm, 28 kilometres (17 mi) northeast of Paso de Indios, Chubut Province, Argentina. They are believed to have been from the Cerro Castaño Member, Cerro Barcino Formation (Aptian stage).[1]

The holotype material was designated MPEF-PV 1156 and included partial dentaries, teeth, back vertebrae 3–8 and 11–14, proximal tail vertebrae, ribs and chevrons, a fragmentary scapulocoracoid, humerus, ulna, partial ilium, a nearly complete femur, fibula, and left metatarsal 2. Additional material (designated MPEF-PV 1157) included jugals, a right dentary, teeth, atlas vertebra, neck vertebra (?) 9, back vertebrae (?)7, 10, 13, fused sacral centra (5 total), an assortment of distal caudals, ribs, the right femur, a fragmentary left metatarsal 2, pedal phalanges 2-1, 2–2, and 3-3.[1]

Description

[edit]

Tyrannotitan was a large animal, reaching 12.2–13 metres (40–43 ft) in length and 4.8–7 t (5.3–7.7 short tons) in body mass.[2][3][4][5][6] Its vertebral column is extensively pneumatized, with pneumatic openings in the dorsal and caudal vertebrae resembling those of Giganotosaurus and Mapusaurus.[7] More unusually, Tyrannotitan shows a pneumatic hiatus in the anterior sacral region, a gap in the invasive pneumaticity of different portions of the vertebral column that were pneumatized by independent segments of the respiratory system (air sacs or their diverticula).[7] Such gaps are most commonly observed in juvenile individuals, whose skeletal pneumaticity has not yet fully developed. [8]

The scapulocoracoid is fused, and much better developed than that of Giganotosaurus carolinii, yet the arm is very small. Most of the shaft of the scapula is missing.[1] The acromion curves about 90 degrees from the shaft axis, making it look vaguely tyrannosaurid-like. Whether the sharp difference between taxa is due to evolution or sexual dimorphism in poorly sampled populations of both species, has not been determined (the latter seems unlikely). A proximal caudal has a very tall neural spine (about twice the height of its centrum, judging by the figure). The base of the orbital fenestra is a notch of nearly 90 degrees into the body of the jugal, which contrasts with the rounded base restored for Giganotosaurus and agrees with Carcharodontosaurus favorably. The denticles on its teeth are "chisel-like", and are virtually identical to those of other carcharodontosaurids in having a wrinkled enamel surface, heavily serrated mesial and distal carinae, and labiolingually compressed (laterally flattened) crowns.[7] The femur of the paratype specimen is 1.4 m (4.6 ft) long according to Novas et al.[1] Canale et al. recover Tyrannotitan as deeply nested within the tribe Giganotosaurini as its most basal member. Characteristics that unite the Giganotosaurini include the presence of a postorbital process on the jugal with a wide base, and a derived femur with a weak fourth trochanter and a shallow broad extensor groove at the distal end.[9][7]

Classification

[edit]In their 2022 description of the large carcharodontosaurine Meraxes. Canale et al. recovered Tyrannotitan within the clade Giganotosaurini, along with Meraxes, Giganotosaurus, and Mapusaurus. The results of their phylogenetic analyses are shown in the cladogram below:[10]

In his 2024 review of theropod relationships, Cau found similar relationships for Tyrannotitan. His results are shown below:[11]

| Carcharodontosauridae |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Novas, F. E.; S. de Valais; P. Vickers-Rich; T. Rich (2005). "A large Cretaceous theropod from Patagonia, Argentina, and the evolution of carcharodontosaurids". Naturwissenschaften. 92 (5): 226–230. Bibcode:2005NW.....92..226N. doi:10.1007/s00114-005-0623-3. hdl:11336/103474. PMID 15834691. S2CID 24015414.

- ^ Rey LV, Holtz, Jr TR (2007). Dinosaurs: the most complete, up-to-date encyclopedia for dinosaur lovers of all ages. United States of America: Random House. ISBN 978-0-375-82419-7.

- ^ Gregory S. Paul (2010). The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs. United States of America: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691137209.

- ^ Campione, Nicolás E.; Evans, David C. (2020). "The accuracy and precision of body mass estimation in non-avian dinosaurs". Biological Reviews. 95 (6): 1759–1797. doi:10.1111/brv.12638. ISSN 1469-185X. PMID 32869488. S2CID 221404013.

- ^ Campione, Nicolás E.; Evans, David C.; Brown, Caleb M.; Carrano, Matthew T. (2014). "Nicolás E. Campione, David C. Evans, Caleb M. Brown, Matthew T. Carrano (2014). Body mass estimation in non-avian bipeds using a theoretical conversion to quadruped stylopodial proportions". Methods in Ecology and Evolution. 5 (9): 913–923. doi:10.1111/2041-210X.12226. S2CID 84317234.

- ^ Persons, S. W.; Currie, P. J.; Erickson, G. M. (2020). "An Older and Exceptionally Large Adult Specimen of Tyrannosaurus rex". The Anatomical Record. 303 (4): 656–672. doi:10.1002/ar.24118. ISSN 1932-8486. PMID 30897281.

- ^ a b c d Canale, Juan Ignacio; Novas, Fernando Emilio; Pol, Diego (2015). "Osteology and phylogenetic relationships of Tyrannotitan chubutensis Novas, de Valais, Vickers-Rich and Rich, 2005 (Theropoda: Carcharodontosauridae) from the Lower Cretaceous of Patagonia, Argentina". Historical Biology. 27 (1): 1–32. Bibcode:2015HBio...27....1C. doi:10.1080/08912963.2013.861830. hdl:11336/17607. S2CID 84583928.

- ^ Melstrom, Keegan M.; D'emic, Michael D.; Chure, Daniel; Wilson, Jeffrey A. (3 July 2016). "A juvenile sauropod dinosaur from the Late Jurassic of Utah, U.S.A., presents further evidence of an avian style air-sac system". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 36 (4): e1111898. Bibcode:2016JVPal..36E1898M. doi:10.1080/02724634.2016.1111898. ISSN 0272-4634.

- ^ "A new carcharodontosaurid (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of Argentina". Geodiversitas. 28 (1): 71–118. 2006.

- ^ Canale, Juan I.; Apesteguía, Sebastián; Gallina, Pablo A.; Mitchell, Jonathan; Smith, Nathan D.; Cullen, Thomas M.; Shinya, Akiko; Haluza, Alejandro; Gianechini, Federico A.; Makovicky, Peter J. (July 2022). "New giant carnivorous dinosaur reveals convergent evolutionary trends in theropod arm reduction". Current Biology. 32 (14): 3195–3202.e5. Bibcode:2022CBio...32E3195C. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2022.05.057. PMID 35803271. S2CID 250343124.

- ^ Cau, Andrea (2024). "A Unified Framework for Predatory Dinosaur Macroevolution" (PDF). Bollettino della Società Paleontologica Italiana. 63 (1): 1-19. doi:10.4435/BSPI.2024.08 (inactive 20 November 2024). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 April 2024. Retrieved 1 May 2024.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link)

- Carcharodontosaurids

- Aptian life

- Early Cretaceous dinosaurs of South America

- Cretaceous Argentina

- Fossils of Argentina

- Cerro Barcino Formation

- Fossil taxa described in 2005

- Taxa named by Fernando Novas

- Taxa named by Patricia Vickers-Rich

- Taxa named by Tom Rich

- Aptian genus first appearances

- Aptian genus extinctions