The Twelve Caesars

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

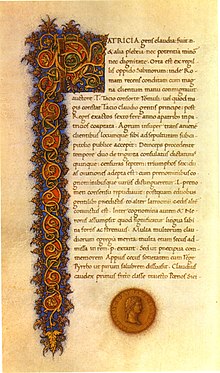

Manuscript of De vita Caesarum, 1477 | |

| Author | Suetonius |

|---|---|

| Original title | De vita Caesarum (lit. 'On the Life of the Caesars') |

| Language | Latin |

| Genre | Biography |

Publication date | AD 121 |

| Publication place | Roman Empire |

De vita Caesarum (Latin; lit. "About the Life of the Caesars"), commonly known as The Twelve Caesars or The Lives of the Twelve Caesars, is a set of twelve biographies of Julius Caesar and the first 11 emperors of the Roman Empire written by Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus. The subjects consist of: Julius Caesar (d. 44 BC), Augustus, Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius, Nero, Galba, Otho, Vitellius, Vespasian, Titus, Domitian (d. 96 AD).

The work, written in AD 121 during the reign of the emperor Hadrian, was the most popular work of Suetonius, at that time Hadrian's personal secretary, and is the largest among his surviving writings. It was dedicated to a friend, the Praetorian prefect Gaius Septicius Clarus.

The Twelve Caesars was considered very significant in antiquity and remains a primary source on Roman history. The book discusses the significant and critical period of the Principate from the end of the Republic to the reign of Domitian; comparisons are often made with Tacitus, whose surviving works document a similar period.

The Twelve Caesars, using the same group, were a popular subject in art in many different media from the Renaissance onwards.

Historicity

[edit]The book can be described as racy, overly sensationalist, packed with gossip, drama, and sometimes humor. The book relies heavily on hearsay and rumor, and at times the author subjectively expresses his opinion and knowledge. Several important events are omitted.[citation needed]

Although he was never a senator himself, Suetonius took the side of the Senate in most conflicts with the princeps, as well as the senators' views of the emperor. That resulted in biases, both conscious and unconscious. Suetonius lost access to the official archives shortly after beginning his work. He was forced to rely on secondhand accounts when it came to Claudius (with the exception of the letters of Augustus, which had been gathered earlier) and does not quote the emperor.[citation needed]

The book still provides valuable information on the heritage, personal habits, physical appearance, lives, and political careers of the first Roman emperors mentioning key details which other sources omit. For example, Suetonius is the main source on the lives of Caligula, his uncle Claudius, and the heritage of Vespasian (the relevant sections of the Annals by his contemporary Tacitus having been lost). Suetonius made a reference in this work to "Chrestus", which could refer to Christ, and in the book on Nero he mentions Christians (see Historicity of Jesus).

Constituent works

[edit]Julius Caesar

[edit]Suetonius begins this section with Caesar's father's death when he himself was aged sixteen. Suetonius then narrates that period describing Caesar's disengagement with a wealthy girl called Cossutia, engagement with Cornelia during the civic strife. He also narrated Caesar's conquests, especially in Gaul, and his Civil War against Pompey the Great. Several times Suetonius quotes Caesar. Suetonius includes Caesar's famous decree, "Veni, vidi, vici" (I came, I saw, I conquered). In discussing Caesar's war against Pompey the Great, Suetonius quotes Caesar during a battle that he nearly lost, "That man [Pompey] does not know how to win a war."

Suetonius describes an incident that would become one of the most memorable of the entire book. As a young man, Caesar was captured by pirates in the Mediterranean Sea. Amused at the lowness of the initial ransom they sought to ask for him, Caesar insisted that they raise his price to 50 talents, and promised that one day he would find them and crucify them (this was the standard punishment for piracy during this time). He spent the remainder of his time in captivity addressing them as subordinates, participating in their games and exercises, and forcing them to listen to his speeches and poetry. After being released a little more than a month later, following the payment of the ransom of 50 talents, Caesar shortly raised an army entirely on his own (despite holding no command or public office), captured the pirates, and crucified them, recovering the 50 talents.

It is from Suetonius that we first learn of another incident during the life of Julius Caesar. While serving as quaestor in Hispania, Caesar once visited a statue of Alexander the Great. Upon viewing this statue, Suetonius reports that Caesar fell to his knees, weeping. When asked what was wrong, Caesar sighed, and said that by the time Alexander was his (Caesar's) age, he had conquered the whole world.

Suetonius describes Caesar's gift at winning the loyalty and admiration of his soldiers. Suetonius mentions that Caesar commonly referred to them as "comrades" instead of "soldiers." When one of Caesar's legions took heavy losses in a battle, Caesar vowed not to trim his beard or hair until he had avenged the deaths of his soldiers. Suetonius describes an incident during a naval battle. One of Caesar's soldiers had his hand cut off. Despite the injury, this soldier still managed to board an enemy ship and subdue its crew. Suetonius mentions Caesar's famous crossing of the Rubicon (the border between Italy and Cisalpine Gaul), on his way to Rome to start a Civil War against Pompey and ultimately seize power.

Suetonius later describes Caesar's major reforms upon defeating Pompey and seizing power. One such reform was the modification of the Roman calendar. The calendar at the time had already used the same system of solar years and lunar months that our current calendar uses. Caesar updated the calendar so as to minimize the number of lost days due to the prior calendar's imprecision regarding the exact amount of time in a solar year. Caesar also renamed the fifth month (also the month of his birth) in the Roman calendar July, in his honor (Roman years started in March, not January as they do under the current calendar). Suetonius says that Caesar had planned on invading and conquering the Parthian Empire. These plans were not carried out due to Caesar's assassination.

Suetonius then includes a description of Caesar's appearance and personality. Suetonius says that Caesar was semi-bald. Due to embarrassment regarding his premature baldness, Caesar combed his hair over and forward so as to hide this baldness. Caesar wore a senator's tunic with an orange belt. Caesar is described as routinely wearing loose clothes. Suetonius quotes the Roman dictator Lucius Cornelius Sulla as saying, "Beware the boy with the loose clothes, for one day he will mean the ruin of the Republic." This quote referred to Caesar, as he had been a young man during Sulla's Social War and subsequent dictatorship. Suetonius describes Caesar as taking steps so that others would not refer to him as king. Political enemies at the time had claimed that Caesar wanted to bring back the much reviled monarchy.

Finally, Suetonius describes Caesar's assassination. Shortly before his assassination, Caesar told a friend that he wanted to die a sudden and spectacular death. Suetonius believes that several omens predicted the assassination. One such omen was a vivid dream Caesar had the night before his assassination. The day of the assassination, Suetonius claims that Caesar was given a document describing the entire plot. Caesar took the document, but did not have a chance to read it before he was assassinated.

Suetonius says that others have claimed that Caesar reproached the conspirator Brutus, saying "You too, my child?" (καὶ σὺ τέκνον, kai su, teknon). This specific wording varies slightly from the more famous quote, "Even you, Brutus?" (et tu, Brute) from Shakespeare's Julius Caesar. However, Suetonius himself asserts that Caesar said nothing, apart from a single groan, as he was being stabbed. Instead Suetonius reports that Caesar exclaimed, "Why, this is violence!" as the attack began.

Augustus

[edit]

Before he died, Julius Caesar had designated his great-nephew, Gaius Octavius (who would be named Augustus by the Roman Senate after becoming emperor), as his adopted son and heir. Octavius' mother, Atia, was the daughter of Caesar's sister, Julia Minor.

Octavian (not yet renamed Augustus) finished the civil wars started by his great-uncle, Julius Caesar. One by one, Octavian defeated the legions of the other generals who wanted to succeed Julius Caesar as the master of the Roman world. Suetonius includes descriptions of these civil wars, including the final one against Mark Antony that ended with the Battle of Actium. Antony had been Octavian's last surviving rival, but committed suicide after his defeat at Actium. It was after this victory in 31 BC that Octavian became master of the Roman world and imperator (emperor). His declaration of the end of the Civil Wars that had started under Julius Caesar marked the historic beginning of the Roman Empire, and the Pax Romana. Octavian at this point was given the title Augustus ("the venerable") by the Roman Senate.

After describing the military campaigns of Augustus, Suetonius describes his personal life. A large section of the entire book is devoted to this. This is partly because after Actium, the reign of Augustus was mostly peaceful. It has also been noted by several sources that the entire work of The Twelve Caesars delves more deeply into personal details and gossip relative to other contemporary Roman histories.

Suetonius describes a strained relationship between Augustus and his daughter Julia. Augustus had originally wanted Julia, his only child, to provide for him a male heir. Due to difficulties regarding an heir, and Julia's promiscuity, Augustus banished Julia to the island of Pandateria and considered having her executed. Suetonius quotes Augustus as repeatedly cursing his enemies by saying that they should have "a wife and children like mine."

According to Suetonius, Augustus lived a modest life, with few luxuries. Augustus lived in an ordinary Roman house, ate ordinary Roman meals, and slept in an ordinary Roman bed.

Suetonius describes certain omens and dreams that predicted the birth of Augustus. One dream described in the book suggested that his mother, Atia, was a virgin impregnated by a Roman god. In 63 BC, during the consulship of Cicero, several Roman senators dreamt that a king would be born, and would rescue the republic. 63 BC was also the year Augustus was born. One other omen described by Suetonius suggests that Julius Caesar decided to make Augustus his heir after seeing an omen while serving as the Roman governor of Hispania Ulterior.

Suetonius includes a section regarding the only two military defeats Rome suffered under Augustus. Both of these defeats occurred in Germany. The first defeat was inconsequential. During the second, the Battle of Teutoburg Forest, three Roman legions (Legio XVII, Legio XVIII, and Legio XIX) were defeated by the West-Germanic resistance to Roman imperialism, led by Arminius. Much of what is known about this battle was written in this book. According to Suetonius, this battle "almost wrecked the empire." It is from Suetonius where we get the reaction of Augustus upon learning of the defeat. Suetonius writes that Augustus hit his head against a wall in despair, repeating, Quintili Vare, legiones redde! ('Quinctilius Varus, give me back my legions!') This defeat was one of the worst Rome suffered during the entire Principate. The result was the establishment of the rivers Rhine and Danube as the natural northern border of the empire. Rome would never again push its territory deeper into Germany. Suetonius suggests that Augustus never fully got over this defeat.

Tiberius

[edit]

Suetonius opens his book on Tiberius by highlighting his ancestry as a member of the patrician Claudii, and recounts his birth father's career as a military officer both under Caesar and as a supporter of Lucius Antonius in his rebellion against Octavian. Upon the resumption of peace, Octavian took an interest in Livia, and requested that the couple divorce so that he could marry her, making Tiberius his stepson. Tiberius's adolescence and marriages are recorded, with Suetonius noting Tiberius's displeasure at being forced by Augustus to divorce his first wife, Vipsania Agrippina, in order to marry Augustus's daughter Julia.[1]

The early successes of Tiberius in his legal, political, and military career are recounted, including his command of several Roman armies in Germany. It was his leadership in these German campaigns that convinced Augustus to adopt Tiberius and to make him his heir. According to Suetonius, Tiberius retired at a young age to Rhodes, before returning to Rome some time before the death of Augustus. The ascent of Tiberius to the throne was possible because the two grandsons that Augustus had died before Augustus, and the last grandson, Postumus Agrippa – although originally designated co-rule with Tiberius – was later deemed morally unsound by Augustus.

Augustus began a long (and at times successful) tradition of adopting an heir, rather than allowing a son to succeed an emperor. Suetonius quotes from the will Augustus left. Suetonius suggests that not only was Tiberius not thought of highly by Augustus, but Augustus expected Tiberius to fail.

After briefly mentioning military and administrative successes, Suetonius tells of perversion, brutality and vice and goes into depth to describe depravities he attributes to Tiberius.

Despite the lurid tales, modern history looks upon Tiberius as a successful and competent emperor[citation needed] who at his death left the state treasury much richer than when his reign began. Thus Suetonius' treatment of the character of Tiberius, like Claudius', must be taken with a pinch of salt.

Tiberius died of natural causes. Suetonius describes widespread joy in Rome upon his death. There was a desire to have his body thrown down the Gemonian stairs and into the Tiber River, as this he had done many times previously to others. Tiberius had no living children when he died, although his (probable) natural grandson, Tiberius Julius Caesar Nero (Gemellus), and his adopted grandson, Gaius Caesar Caligula, both survived him. Tiberius designated both as his joint heirs, but seems to have favored Caligula over Gemellus, due to Gemellus' youth.

Caligula

[edit]

Most of what is known about the reign of Caligula comes from Suetonius. Other contemporary Roman works, such as those of Tacitus, contain little, if anything, about Caligula. Presumably most of what existed regarding his reign was lost long ago.

For most of the work, Suetonius refers to Caligula by his actual first name, Gaius. Caligula ('little boots') was a nickname given to him by his father's soldiers, because as a boy he would often dress in miniature battle gear and 'drill' the troops (without knowing the commands, but the troops loved him all the same and pretended to understand him). Caligula's father, Germanicus, was loved throughout Rome as a brilliant military commander and example of Roman pietas. Tiberius had adopted Germanicus as his heir, with the hope that Germanicus would succeed him. Germanicus died before he could succeed Tiberius in 19 AD.

Upon the death of Tiberius, Caligula became emperor. Initially the Romans loved Caligula due to their memory of his father. But most of what Suetonius says of Caligula is negative, and describes him as having an affliction that caused him to suddenly fall unconscious. Suetonius believed that Caligula knew that something was wrong with him.

He reports that Caligula married his sister, threatened to make his horse consul, and that he sent an army to the northern coast of Gaul and as they prepared to invade Britain, one rumour had it that he had them pick seashells on the shore (evidence shows that this could be a fabrication as the word for shell in Latin doubles as the word that the legionaries of the time used to call the 'huts' that the soldiers erected during the night while on campaign). He once had a walkway built from his palace to a temple so that he could be closer to his "brother," the Roman god Jupiter, as Caligula believed himself to be a living deity. He would also have busts of his head replace those on statues of different gods.

He would call people to his palace in the middle of the night. When they arrived, he would hide and make strange noises. At other times, he would have people assassinated, and then call for them. When they did not show up, he would remark that they must have committed suicide.

Suetonius describes several omens that predicted the assassination of Caligula. He mentions a bolt of lightning that struck Rome on the ides of March, which was when Julius Caesar was assassinated. Lightning was an event of immense superstition in the ancient world. The day of the assassination, Caligula sacrificed a flamingo. During the sacrifice, blood splattered on his clothes. Suetonius even suggested that Caligula's name itself was a predictor of his assassination, noting that every caesar named Gaius, such as the dictator Gaius Julius Caesar, had been assassinated (a statement which is not entirely accurate; Julius Caesar's father died from natural causes, as did Augustus).

Caligula was an avid fan of gladiatorial combats; he was assassinated shortly after leaving a show by a disgruntled Praetorian Guard captain, as well as several senators.

Claudius

[edit]

Claudius (full name: Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus) was the grandson of Mark Antony, brother of Germanicus, and the uncle of Caligula. He was descended from both the Julian and the Claudian clans, as was Caligula. He was about 50 years old at the time of Caligula's murder. He never held public office until late in his life, mainly due to his family's concerns as to his health and mental abilities. Suetonius has much to say about Claudius' apparent disabilities, and how the imperial family viewed them, in the "Life of Augustus".

The assassination of Caligula caused great terror in the palace and, according to Suetonius, Claudius, being frightened by the sounds of soldiers scouring the palace for further victims, hid behind some curtains on a balcony nearby. He was convinced that he would be murdered as well because he was within direct family of Caligula, the last emperor. A soldier checking the room noticed feet sticking out from underneath the curtains, and upon pulling back the curtains discovered a terrified Claudius. He acclaimed Claudius the new emperor and took him to the rest of the soldiers, where they carried him out of the palace on a litter. Claudius was taken to the Praetorian camp, where he was quickly proclaimed emperor by the troops.

We learn from Suetonius that Claudius was the first Roman commander to invade Britain since Julius Caesar a century earlier. Cassius Dio gives a more detailed account of this. He also went farther than Caesar, and made Britain subject to Roman rule. Caesar had "conquered" Britain, but left the Britons alone to rule themselves. Claudius was not as kind. The invasion of Britain was the major military campaign under his reign.

According to Suetonius, Claudius suffered from ill health all of his life until he became emperor, when his health suddenly became excellent. Nonetheless, Claudius suffered from a variety of maladies, including fits and epileptic seizures, a funny limp, as well as several personal habits like a bad stutter and excessive drooling when overexcited. Suetonius found much delectation in recounting how the pitiable Claudius was ridiculed in his imperial home due to these ailments. In his account of Caligula, Suetonius also includes several letters written by Augustus to his wife, Livia, expressing concern for the imperial family's reputation should Claudius be seen with them in public. Suetonius goes on to accuse Claudius of cruelty and stupidity, assigning some of the blame to his wives and freedmen.

Suetonius discusses several omens that foretold the assassination of Claudius. He mentions a comet that several Romans had seen shortly before the assassination. As mentioned earlier, comets were believed to foretell the deaths of significant people. Per Suetonius, Claudius, under suggestions from his wife Messalina, tried to shift this deadly fate from himself to others by various fictions, resulting in the execution of several Roman citizens, including some senators and aristocrats.

Suetonius paints Claudius as a ridiculous figure, belittling many of his acts and attributing his good works to the influence of others. Thus the portrait of Claudius as the weak fool, controlled by those he supposedly ruled, was preserved for the ages. Claudius' dining habits figure in the biography, notably his immoderate love of food and drink, and his affection for the city taverns.

His personal and moral failings aside however, most modern historians agree that Claudius generally ruled well. They cite his military success in Britannia as well as his extensive public works. His reign came to an end when he was murdered by eating from a dish of poisoned mushrooms, probably supplied by his last wife Agrippina in an attempt to have her own son from a previous marriage, the future emperor Nero, ascend the throne.

Nero

[edit]

Suetonius portrays the life of Nero in a similar fashion to that of Caligula—it begins with a recounting of how Nero assumed the throne ahead of Claudius' son Britannicus and then descends into a recounting of various atrocities the young emperor allegedly performed.

One characteristic of Nero that Suetonius describes was Nero's enjoyment of music. Suetonius describes Nero as being a gifted musician. Nero would often give great concerts with attendance compelled for upper-class Romans. These concerts would last for hours on end, and some women were rumored to give birth during them, or men faking death to escape (Nero forbade anyone from leaving the performance until it was completed).

Nero's eccentricities continued in the tradition of his predecessors in mental and personal perversions. According to Suetonius, Nero had one boy named Sporus castrated, and then had sex with him as though he were a woman. Suetonius quotes one Roman who lived around this time who remarked that the world would have been better off if Nero's father Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus had married someone more like the castrated boy.

It is in Suetonius we find the beginnings of the legend that Nero "fiddled as Rome burned." Suetonius recounts how Nero, while watching Rome burn, exclaimed how beautiful it was, and sang an epic poem about the sack of Troy while playing the lyre.

Suetonius describes Nero's suicide, and remarks that his death meant the end of the reign of the Julio-Claudians (because Nero had no heir). According to Suetonius, Nero was condemned to die by the Senate. When Nero knew that soldiers had been dispatched by the Senate to kill him, he committed suicide.

Galba

[edit]

The book about Galba is short. Galba was the first emperor of the Year of the Four Emperors.

Galba was able to ascend to the throne because Nero's death meant the end of Julio-Claudian dynasty.

Suetonius includes a brief description of Galba's family history. Suetonius describes Galba as being of noble birth, and born into a noble patrician family. Suetonius also includes a brief list of omens regarding Galba and his assassination.

Most of this book describes Galba's ascension to the throne and his assassination, along with the usual side notes regarding his appearance and related omens. Suetonius does not spend much time describing either any accomplishments nor any failures of his reign.

According to Suetonius, Galba was killed by Otho's loyalists.

About this time, Suetonius has exhausted all his imperial archival sources.

Otho

[edit]

His full name was Marcus Salvius Otho. Otho's reign was only a few months. Therefore, the book on Otho is short, much as the book on Galba had been.

Suetonius used a similar method to describe the life of Otho as he had used to describe the life of Galba. Suetonius describes Otho's family, and their history and nobility. And just as Suetonius had done with prior caesars, he includes a list of omens regarding Otho's reign and suicide.

Suetonius spends most of the book describing the ascension of Otho, his suicide, and the other usual topics. Suetonius suggests that as soon as Otho ascended the throne, he started defending himself against competing claims to the throne.

According to Suetonius, Otho suffered a fate similar to the fate Galba had suffered. It was the loyalists of another aspiring emperor (in this case, the next emperor Vitellius) who wanted to kill him. Suetonius claims that one night Otho realized that he would soon be murdered. He contemplated suicide, but decided to sleep one more night before carrying out a suicide. That night he went to bed with a dagger under his pillow. The next morning he woke up and stabbed himself to death.

Vitellius

[edit]

In the book of the last of the short-lived emperors, Suetonius briefly describes the reign of Vitellius.

This book gives an unfavorable picture of Vitellius; however it should be remembered that Suetonius' father was an army officer who had fought for Otho and against Vitellius at the first Battle of Bedriacum, and that Vespasian basically controlled history when he ascended to the throne. Anything written about Vitellius during the Flavian dynasty would have to paint him in a bad light.

Suetonius includes a brief description of the family history of Vitellius, and related omens.

Suetonius finally describes the assassination of Vitellius. According to Suetonius, Vitellius was dragged naked by Roman subjects, tied to a post, and had animal waste thrown at him before he was killed. However, unlike the prior two emperors, it was not the next emperor who killed Vitellius. The next emperor and his followers had been waging a war against the Jews in Judaea at the time. The death of Vitellius and subsequent ascendance of his successor ended the worst year of the early principate.

Vespasian

[edit]Suetonius begins by describing the humble antecedents of the founder of the Flavian dynasty and follows with a brief summary of his military and political career under Aulus Plautius, Claudius and Nero and his suppression of the uprising in Judaea. Suetonius documents an early reputation for honesty but also a tendency toward avariciousness.

A detailed recounting of the omens and consultations with oracles follows which Suetonius suggests furthered Vespasian's imperial pretensions. Suetonius then briefly recounts the escalating military support for Vespasian and even more briefly the events in Italy and Egypt that culminated in his accession.

Suetonius presents Vespasian's early imperial actions, the reimposition of discipline on Rome and her provinces and the rebuilding and repair of Roman infrastructure damaged in the civil war, in a favourable light, describing him as 'modest and lenient' and drawing clear parallels with Augustus. Vespasian is further presented as being extraordinarily just and with a preference for clemency over revenge.

Suetonius describes avarice as Vespasian's only serious failing, documenting his tendency for inventive taxation and extortion. However, he mitigates this failing by suggesting that the emptiness of state coffers left Vespasian little choice. Moreover, intermixed with accounts of greed and 'stinginess' are accounts of generosity and lavish rewards. Finally Suetonius gives a brief account of Vespasian's physical appearance and penchant for comedy. This section of the work is the basis for the famous expression "Money has no odor" (Pecunia non olet); according to Suetonius, Vespasian's son (and the next emperor), Titus, criticized Vespasian for levying a fee for the use of public toilets in the streets of Rome. Vespasian then produced some coins and asked Titus to sniff them, and then asked Titus whether they smelled bad. When Titus said that the coins did not smell bad, Vespasian replied: "And yet they come from urine".

Having contracted a 'bowel complaint,' Vespasian tried to continue his duties as emperor from what would be his deathbed, but on a sudden attack of diarrhea he said "An emperor ought to die standing," and died while struggling to do so.

Titus

[edit]

Titus was the elder son of Vespasian, and second emperor of the Flavian dynasty. As Suetonius writes: "The delight and darling of the human race." Titus was raised in the imperial court, having grown up with Britannicus. The two of them were told a prophecy pertaining to their future where Britannicus was told that he would never succeed his father and that Titus would. The two were so close that when Britannicus was poisoned, Titus – who was present – tasted it and was nearly killed. "When Titus came of age, the beauty and talents that had distinguished him as a child grew even more remarkable." Titus was extremely adept at the arts of "war and peace." He made a name for himself as a colonel in Germany and Britain; however, he really flourished as a commander under his father in Judea and when he took over the siege of Jerusalem. Titus' near six-month siege of Jerusalem ended with the destruction of Herod's Temple and the expulsion of Jews from Jerusalem. The resulting period is known as the Jewish diaspora (roughly from 70 till 1948). Titus had a love affair with the Jewish queen Berenice, whom he brought briefly to Rome.

As emperor, he tried to be magnanimous and always heard petitions with an open mind. And after going through a day having not granted any favors, he commented that "I have wasted a day." During his reign he finished what would be the most enduring reminder of his family: the Flavian Amphitheater. His reign was tainted by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, a great fire in Rome, and one of the worst plagues "that had ever been known." These catastrophes did not destroy him. Rather, as Suetonius remarks, he rose up like a father caring for his children. And although he was deified, his reign was short. He died from poison (possibly by his brother, Domitian), having only reigned for "two years, two months and twenty days." At the time of his death, he "[drew] back the curtains, gazed up at the sky, and complained bitterly that life was being undeservedly taken from him – since only a single sin lay on his conscience."

Domitian

[edit]

Younger brother of Titus, second son of Vespasian, and third emperor of the Flavian dynasty. Recorded as having gained the throne through deliberately letting his brother die of a fever. During Titus' rule he had caused dissent and had sought the throne through rebellion. From the beginning of his reign Domitian ruled as a complete autocrat, partly because of his lack of political skills, but also because of his own nature. Having led a solitary early life, Domitian was suspicious of those around him, a difficult situation which gradually got worse.

Domitian's provincial government was so carefully supervised that Suetonius admits that the empire enjoyed a period of unusually good government and security. Domitian's policy of employing members of the equestrian class rather than his own freedmen for some important posts was also an innovation. The empire's finances, which the recklessness of Titus had thrown into confusion, were restored despite building projects and foreign wars. Deeply religious, Domitian built temples and established ceremonies and even tried to enforce public morality by law.

Domitian personally took part in battles in Germany. The latter part of his reign saw increasing trouble on the lower Danube from the Dacians, a tribe occupying roughly what is today Romania. Led by their king Decebalus, the Dacians invaded the empire in 85 AD. The war ended in 88 in a compromise peace which left Decebalus as king and gave him Roman "foreign aid" in return for his promise to help defend the frontier.

One of the reasons Domitian failed to crush the Dacians was a revolt in Germany by the governor Antonius Saturninus. The revolt was quickly suppressed, but from then on, Suetonius informs us, Domitian's already suspicious temper grew steadily worse. Those closest to him suffered the most, and after a reign of terror at the imperial court Domitian was murdered in 96 AD; the group that killed him, according to Suetonius, included his wife, Domitia Longina, and possibly his successor, Nerva. The Senate, which had always hated him, quickly condemned his memory and repealed his acts, and Domitian joined the ranks of the tyrants of considerable accomplishments but evil memory. He was the last of the Flavian emperors, and his murder marked the beginning of the period of the so-called Five Good Emperors.

Manuscript tradition

[edit]The oldest surviving copy of The Twelve Caesars was made in Tours in the late 8th or early 9th century AD, and is currently held in the Bibliothèque nationale de France. It is missing the prologue and the first part of the life of Julius Caesar, as are all other surviving copies of the book. Including the Tours manuscript, there are nineteen surviving copies of The Twelve Caesars from the 13th century or earlier. The presence of certain errors in some copies but not others suggests that the nineteen books can be split into two branches of transmission of roughly equal size.[2][3]

References to the book appear in older works. John Lydus, in his 6th-century book De magistratibus populi Romani, quotes the dedication (from the now-lost prologue) to Septicius Clarus, then prefect of the Praetorian cohort. This allows the book to be dated to 119–121 AD, when Septicius was Praetorian prefect.[4]

Extant manuscripts (ninth to thirteenth centuries)

[edit]Alpha branch

[edit]Current location |

Century |

Location it was transcribed |

|---|---|---|

Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France lat. 6115 |

s. IX 1/2 |

Tours |

Wolfenbüttel, Herzog August Bibliothek 4573 Gud. lat. 268 |

s. XI 3/4 |

Eichstätt |

Vatican, Bibliotheca Apostolica Vaticana lat. 1904 |

s. XI 1/2 |

Flavigny? |

Florence, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana Plut. 68.7 |

s. XII 2/2 |

France? |

Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France lat. 5801 |

s. XI/XII |

Chartres or Le Mans? |

Florence, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana Plut. 66.39 |

s. XII med. |

France |

Vatican, Bibliotheca Apostolica Vaticana Reg. lat. 833 |

s. XII 2/2 |

France |

Montpellier, Faculté de médecine 117 |

s. XII med. |

Clairvaux? |

Beta branch

[edit]Current location |

Century |

Location it was transcribed |

|---|---|---|

London, British Library Royal 15 C. iii |

s. XII in. |

London, St. Paul's |

Oxford, Bodleian Library Lat. class. d. 39 |

s. XII 3/4 |

England |

London, British Library Royal 15 C. iv |

s. XIII |

England |

Soissons, Bibliothèque municipale 19 |

s. XIII |

Presumably of French origin |

Cambridge, University Library Kk.5.24 |

s. XII 2/2 |

England? |

Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France lat. 5802 |

s. XII med. |

Chartres? |

Durham, Cathedral Library C.III.18 |

s. XI ex. |

England? France? |

Florence, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana Plut. 64.8 |

s. XII 2/2 |

France? |

Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France lat. 6116 |

s. XII med. |

Normandy? |

San Marino, Huntington Library HM 45717 |

s. XII ex. |

Bury St. Edmunds |

As identified and assigned in Kaster.[5]

"In." indicates that the manuscript is believed to originate around the beginning of that century. "Med." indicates towards the middle and "Ex." indicates towards the end. Otherwise the number indicates first (1/2) or second half (2/2) of the century or one of the quarters of the century (1-4/4).

Influence

[edit]The Twelve Caesars served as a model for the biographies of 2nd- and early 3rd-century emperors compiled by Marius Maximus. This collection, apparently entitled Caesares, does not survive, but it was a source for a later biographical collection, known as Historia Augusta, which now forms a kind of sequel to Suetonius' work. The Historia Augusta is a collective biography, partly fictionalized, of Roman emperors and usurpers of the second and third centuries.

In the ninth century, Einhard modelled himself on Suetonius in writing the Life of Charlemagne, even borrowing phrases from Suetonius' physical description of Augustus in his own description of the character and appearance of Charlemagne.

Robert Graves, famous for his historical novels I, Claudius and Claudius the God (later dramatized by the BBC), made a widely read translation of The Twelve Caesars, first published in Penguin Classics in 1957.

Suetonius' work has had a significant impact on coin collecting. For centuries, collecting a coin of each of the twelve caesars has been a challenge for collectors of Roman coins.[6]

Many artists created series of paintings or sculptures based on the lives of the Twelve Caesars, including Titian's Eleven Caesars, and the Aldobrandini Tazze, a collection of twelve 16th-century silver standing cups.

Complete editions and translations

[edit]- Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus, The Twelve Caesars, tr. Robert Graves. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1957, revised by James B. Rives, 2007

- C. Suetoni Tranquilli opera, vol. I: De vita Caesarum libri VIII, ed. Maximilianus Ihm. Leipzig: Teubner, 1908.

- Suetonius, with an English translation by J. C. Rolfe. London: Heinemann, 1913–4.

- Suetonius. The Twelve Caesars (Titus). (London: Penguin, 1979), pp. 296–302.

Individual lives

[edit]- Suetonius, Divus Iulius [Life of Julius Caesar] ed. H. E. Butler, M. Cary. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1927. Reissued with new introduction, bibliography and additional notes by G.B. Townend. Bristol: Bristol Classical Press, 1982.

- Suetonius, Divus Augustus ed. John M. Carter. Bristol: Bristol Classical Press, 1982.

- Phillips, Darryl Alexander, ed. (2023). Suetonius' Life of Augustus. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780197676080.

- Suetonius, Tiberius ed. Hugh Lindsay. London: Bristol Classical Press, 1995.

- Suetonius, Caligula ed. Hugh Lindsay. London: Bristol Classical Press, 1993.

- D. Wardle, Suetonius' Life of Caligula: a commentary. Brussels: Latomus, 1994.

- Suetonius, Claudius ed. J. Mottershead. Bristol: Bristol Classical Press, 1986.

- Suetonius, Nero ed. B.H. Warmington. London: Bristol Classical Press, 1999.

- Suetonius, Galba, Otho, Vitellius ed. Charles L. Murison. London: Bristol Classical Press, 1992.

- Suetonius, Divus Vespasianus ed. A. W. Braithwaite. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1927.

- Suetonius, Domitian ed. Brian W. Jones. Bristol: Bristol Classical Press, 1996.

- Hans Martinet, C. Suetonius Tranquillus, Divus Titus: Kommentar. Königstein am Taunus: Hain, 1981.

Bibliography

[edit]This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (November 2014) |

- A. Dalby, 'Dining with the Caesars' in Food and the memory: papers of the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery 2000 ed. Harlan Walker (Totnes: Prospect Books, 2001) pp. 62–88.

- A. Wallace-Hadrill, Suetonius: the scholar and his Caesars. London: Duckworth, 1983.

References

[edit]- ^ "The Lives of the Twelve Caesars, by C. Suetonius Tranquillus;". www.gutenberg.org. Retrieved 2021-10-18.

- ^ Smith, Clement Lawrence (1901). "A Preliminary Study of Certain Manuscripts of Suetonius' Lives of the Caesars". Harvard Studies in Classical Philology. 12: 19–58. doi:10.2307/310421. hdl:2027/mdp.39015074725345. JSTOR 310421.

- ^ Kaster, Robert A (Spring 2014). "The Transmission of Suetonius's Caesars in the Middle Ages" (PDF). Transactions of the American Philological Association. 144 (1): 133–186. doi:10.1353/apa.2014.0000. S2CID 162389359.

- ^ Henderson, John (2014). ""Was Suetonius' Julius a Caesar?"". In Power, Tristan; Gibson, Roy K (eds.). Suetonius the Biographer: Studies in Roman Lives. Oxford Scholarship Online. p. 81. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199697106.003.0005. ISBN 978-0-19-969710-6.

- ^ Kaster, Robert A (Spring 2014). "The Transmission of Suetonius's Caesars in the Middle Ages" (PDF). Transactions of the American Philological Association. 144 (1): 133–186. doi:10.1353/apa.2014.0000. S2CID 162389359.

- ^ Markowitz, Mike (15 March 2016). "Coins of the Twelve Caesars". CoinWeek. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

External links

[edit]- The Lives of the Caesars at Standard Ebooks

- The Lives of the Twelve Caesars at LacusCurtius (Latin and translation from Loeb Classical Library (1914) by John Carew Rolfe)

- Suetonius' works at Latin Library (in Latin)

- Works by Suetonius at Project Gutenberg

- The Lives of the Twelve Caesars at Project Gutenberg (English translation of Alexander Thomson, M.D., Revised and corrected by T. Forester, Esq., A.M. – includes Lives Of The Grammarians, Rhetoricians, And Poets. 1796)

The Lives of the Twelve Caesars public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Lives of the Twelve Caesars public domain audiobook at LibriVox- Gai Suetoni Tranquilli De vita Caesarum libri III–VI Cornell University Library Historical Monographs Collection.

- The Twelve Caesars at Poetry in Translation (New English translation with in-depth name index (2010) by A. S. Kline)