Truth: Red, White & Black

| Truth: Red, White & Black | |

|---|---|

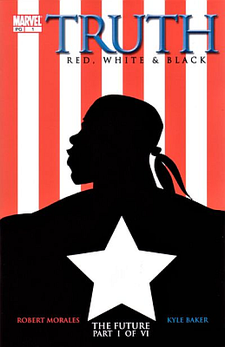

Issue #1 of Truth: Red, White & Black (Jan 2003). Pencils and inks by Kyle Baker. | |

| Publication information | |

| Publisher | Marvel Comics |

| Schedule | Monthly |

| Format | Limited series |

| Publication date | January - July 2003 |

| No. of issues | 7 |

| Main character(s) | Captain America (Isaiah Bradley) |

| Creative team | |

| Written by | Robert Morales |

| Penciller(s) | Kyle Baker |

| Inker(s) | Kyle Baker |

| Letterer(s) | Wes Abbott |

| Colorist(s) | Kyle Baker |

| Editor(s) | Axel AlonsoJohn Miesegaes |

Truth: Red, White & Black is a seven-issue comic book limited series written by Robert Morales, drawn by Kyle Baker and published by Marvel Comics. The series focuses on Isaiah Bradley, one of 300 African American soldiers experimented on by the US Army in an attempt to create super soldiers. Elements of Truth are adapted for the Disney+ series The Falcon and the Winter Soldier, set in the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

Publication history

[edit]Published from January 2003 to July 2003, the series Truth: Red, White & Black is composed of seven comics: "The Future",[1] "The Basics",[2] "The Passage",[3] "The Cut",[4] "The Math",[5] "The Whitewash"[6] and "The Blackvine".[7] The series was announced as six issue series, but was later extended to seven. The cover of the first two issues include the text "Part I of VI" and "Part II of VI"; the later issues read "... of VII".[8]

The trade paperback collecting the series was published in February 2004[9] and the hardcover in 2009. The book version of Truth contains Morales's appendix in which he clarifies myth, history and imagination and provides sources for his story.[10] A new trade paperback edition was released in February 2022, under the title Captain America: Truth.[11]

Concept and creation

[edit]The original concept for the character came from an offhand comment by Marvel's publisher, Bill Jemas.[12] Axel Alonso was taken by the idea "inherent of politics of wrapping a Black man in red, white, and blue" and "a larger story ... a metaphor of America itself"; he also immediately thought of the Tuskegee Study.[12] In a meeting involving Joe Quesada,[13] Alonso proceeded to pitch the idea to Robert Morales, who was brought in to write the story and create the supporting cast and the ending.[12] The idea of an African American Captain America made Morales laugh, but, once he heard the premise, he found it depressing.[12] He says he "wrote a proposal that was so staggeringly depressing I was certain they'd turn it down. But they didn't."[13]

Morales originally envisioned the character as a young scientist prodigy who became the accidental victim of his own experiment, a nod to Silver Age scientists Reed Richards and Bruce Banner; however, Marvel wanted a more explicit reference to the Tuskegee Syphilis Study.[12] He was able to push through an ending in which Bradley suffered brain damage, a reference to Muhammad Ali that gave the character a tragic ending.[12] Morales was disappointed in having to get rid of his idea for a Black scientist, but he was consoled to know that the most important story element, a strong Black marriage, had remained at the core. He performed extensive research into the time period, which he balanced with editorial suggestions.[12] Bradley's strong marriage came from an unsuccessful Luke Cage proposal by Brian Azzarello.

Synopsis

[edit]Set in the Marvel Universe, the series takes the Tuskegee Experiments as inspiration for a tale that re-examines the history of the super-soldier serum that created Captain America.[13] Beginning in 1942, the series follows a regiment of black soldiers who are forced to act as test subjects in a program attempting to re-create the lost formula earlier used to turn Steve Rogers into Captain America.[14] The experiments lead to mutation and death, until only one remains: Isaiah Bradley.

| No. | Title | English release date | English ISBN |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | The Future | January 1, 2003[1] | — |

| The story begins by introducing three Black men: Isaiah Bradley (Queens, June 1940); Maurice Canfield (Philadelphia, December 1940); and Sergeant Luke Evans (Cleveland, June 1941). The everyday racism is shown: Bradley and his wife Faith are denied entry to a peep show at the Amusement Area of the World's Fair; Canfield was beaten by resentful stevedores while trying to organize them into a union; and Evans was demoted from Captain after protesting the unjust death of a friend. After the attack on Pearl Harbor and the subsequent entry of the United States into World War II, all three men are enlisted into active military duty. | |||

| 2 | The Basics | February 1, 2003[2] | — |

| At Camp Cathcart, Mississippi in May 1942, Sgt. Evans leads the new recruits through basic training. The camp commandant, Major Brackett, entertains guests (Mr. Tully and Dr. Reinstein) who request two battalions of Black soldiers "to see if [their] methods apply to the inferior races". Brackett assembles the troops at 2300 that night; Tully and Reinstein attend, accompanied by Colonel Walker Price of Military Intelligence. Price shoots and kills Brackett, then asks his aide Lieutenant Merritt to select 300 soldiers and get them onto trucks; it is implied the remaining soldiers at Camp Cathcart were killed that night to preserve the project's secrecy. | |||

| 3 | The Passage | March 1, 2003[3] | — |

| While the families and friends of Bradley, Canfield, and Evans are being told the men have died in training accidents, the soldiers have been taken to an underground bunker, where they are injected with the super soldier serum. Ultimately, fewer than ten men survive the serum treatments; they board a ship (HMS Pynchon) for an unknown destination. | |||

| 4 | The Cut | April 1, 2003[4] | — |

| In July 1942, the super soldiers have halted a convoy in Germany's Black Forest, but they are dismayed to discover they have succeeded only in stopping medical supplies from Koch Pharmaceuticals. Two months later, in Sintra, Portugal, only three soldiers remain: Bradley, Canfield, and Evans. The trio are discussing the uncanny parallels between comic book hero Captain America and their serum treatments when Merritt goads Canfield into a fight; while trying to restrain Canfield, both Evans and Canfield are killed and Bradley is injured. Price tells Bradley his family's survival depends on the United States winning the war and then describes a 'suicide' mission that Steve Rogers would have taken in Germany, were he not delayed by weather in the Pacific theatre. | |||

| 5 | The Math | May 1, 2003[5] | — |

| In October 1942, Bradley steals the Captain America suit and parachutes behind enemy lines in Schwarzebitte, Germany, where he successfully completes the 'suicide' mission to destroy a laboratory operated by Dr. Koch as a Nazi concentration camp. After killing Koch, while seeking shelter from gunfire, he enters a gas chamber filled with women; the gas kills them, but only weakens Bradley, and he is captured. The story flashes forward to the present day and closes with Steve Rogers in conversation with a woman in a burqa, who asks why Rogers thinks Bradley is dead. | |||

| 6 | The Whitewash | June 1, 2003[6] | — |

| Five days before his visit with the woman, Rogers questions Merritt, now incarcerated in Lompoc Federal Prison; Merritt is implicated in the destruction of Reinstein's notes, and Rogers confronts him with photographic evidence of Merritt's sympathy with Nazi causes, including the scraps of a Captain America uniform. Flashing back to 1942, Adolf Hitler and Joseph Goebbels make a proposal to a captive Bradley: fight for Nazi Germany, and they pledge to free Black people in America; Bradley simply replies "Guys, no. My wife would kill me." Shifting back to the present, Merritt explains how experiments on the Black soldiers were used to recreate the super-soldier serum first used on Rogers and how Nazi Germany came to capture Bradley; although both Merritt and FBI Agent Spinrad (who is assisting Rogers) are familiar with the story of Isaiah Bradley, it is the first time Rogers has heard of him. As they walk away from an agitated Merritt, Spinrad tells Rogers how his grandfather helped Bradley escape Nazi custody. | |||

| 7 | The Blackvine | July 1, 2003[7] | — |

| Rogers confronts Walker Price in Arlington National Cemetery and learns that Reinstein and Koch once were collaborators on a joint American-German super-soldier serum project before World War II; the convoy the Black soldiers had disrupted was resupplying Koch's continuation of the project, which was being conducted at the laboratory and concentration camp that Bradley subsequently destroyed. Faith Bradley is revealed as the woman in the burqa; after Isaiah was repatriated in April 1943, he was incarcerated in Leavenworth for stealing the uniform before being pardoned by Eisenhower in 1960. Although he survived, the serum and lack of treatment during his imprisonment left Isaiah with brain damage and he has reverted to childhood mentally; he remains popular and well-known in the Black community, and the walls of the apartment are covered with pictures in which he poses with celebrities. Faith takes a picture of Isaiah and Rogers together to add to the wall, with Isaiah wearing the shredded uniform confiscated from Merritt. | |||

Analysis

[edit]In Super Black: American Pop Culture and Black Superheroes, Adilifu Nama notes that "Truth admonished the reader to incorporate the experiences and histories of black folk that paint a different picture of the cost and quest for freedom and democracy in America."[15]

Critical reaction

[edit]Axel Alonso felt some of the criticism for this series came from "outright racists who just don't like the idea of a black man in the Cap uniform."[13]

In an interview with Comic Book Resources, he recalled:

When we posted our first image of Isaiah Bradley – the silhouette of an African American man in a Captain America costume – the media latched onto it as a story of interest, but a lot of internet folks lined up against it, assuming, for whatever reason, that it would disparage the legacy of Steve Rogers. By the time the story was done, the dialog around the series had substantially changed. One high-profile reviewer even wrote a column admitting he'd unfairly pre-judged the series, that he now saw it was about building bridges between people, not burning them – which I deeply respected. It's especially meaningful when you edit a story that functions as a little more than pure entertainment.[16]

Captain America timeline

[edit]Clarifying the timeline for Isaiah Bradley and Steve Rogers—and who predates whom—Robert Morales states in his appendix to the Truth: Red, White & Black trade paperback collection (2004):

Truth was originally planned to be outside of the Marvel Universe's official continuity. The editorial decision to place it into continuity meant explaining Timely Comics' first publication of Joe Simon and Jack Kirby’s Captain America in 1940—a full year before Pearl Harbor and the true start of our story.

Truth co-creator Kyle Baker further clarified the respective timelines of Bradley and Rogers in an interview:

With Captain America, people get on my case for 'changing' Captain America. We got a lot of grief from the Captain America fans on that series until the fifth and sixth issues came out; when it turned out that we hadn't tinkered with the continuity. Before that, everybody was very upset, because our story started with Pearl Harbor, and everybody knows that the first issue of Captain America took place before Pearl. Somewhere in the middle of the series, it's revealed that Cap already existed, and we hadn't tinkered with the timeline, and suddenly, the book is okay.[14]

In other media

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2021) |

Elements of the comic are adapted for the Disney+ series The Falcon and the Winter Soldier, set in the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Truth: Red, White and Black (2003) #1". Marvel. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

- ^ a b "Truth: Red, White and Black (2003) #2". Marvel. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

- ^ a b "Truth: Red, White and Black (2003) #3". Marvel. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

- ^ a b "Truth: Red, White and Black (2003) #4". Marvel. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

- ^ a b "Truth: Red, White and Black (2003) #5". Marvel. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

- ^ a b "Truth: Red, White and Black (2003) #6". Marvel. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

- ^ a b "Truth: Red, White and Black (2003) #7". Marvel. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

- ^ "GCD :: Series :: Truth: Red, White & Black". GCD. The Grand Comics Database. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- ^ "Truth: Red, White & Black (Trade Paperback)". Marvel Comics. February 4, 2004. Retrieved 24 April 2021. ISBN 0-7851-1072-0

- ^ Weinstein, Matthew (2010). Bodies Out of Control: Rethinking Science Texts. Peter Lang. p. 126. ISBN 978-1-4331-0515-9.

- ^ "Captain America: Truth (Trade Paperback)".

- ^ a b c d e f g Carpenter, Standford W. (2007). "Authorship and Creation of Black Captain America". In McLaughlin, Jeff (ed.). Comics as Philosophy. University Press of Mississippi. pp. 53–58. ISBN 9781604730661. Retrieved 2013-08-17.

- ^ a b c d Tom Sinclair (November 22, 2002). "Black in Action". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved December 20, 2011.

- ^ a b Brady, Matt (2003-07-07). "Newsarama - Baker's Future In Plastic: Kyle Baker On Plastic Man". newsarama.com. Archived from the original on 2009-03-02. Retrieved 2013-08-17.

- ^ Adilifu Nama (2011). Super Black: American Pop Culture and Black Superheroes. University of Texas Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-292-74252-9.

- ^ "Axel-In-Charge: Axel's Early Years". 7 July 2023.

External links

[edit]- Truth: Red, White & Black at the Grand Comics Database

- Truth: Red, White & Black at the Comic Book DB (archived from the original)

- Reliving World War II With a Captain America of a Different Color, New York Times, December 1, 2002

- Review: Truth: Red, White, and Black at PaperbackReader.com

- Truth made visible: crises of cultural expression in truth: Red, White, and Black.

- Remediating Blackness and the Formation of a Black Graphic Historical Novel Tradition by Adam Kendall Coombs, Master These.