Étienne Léopold Trouvelot

Étienne Léopold Trouvelot | |

|---|---|

Étienne Trouvelot, c. 1870 | |

| Born | December 26, 1827 Aisne, France |

| Died | April 22, 1895 (aged 67) Meudon, France |

| Known for | Introducing Spongy moth (formerly gypsy moth) to North America |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Astronomy |

Étienne Léopold Trouvelot (December 26, 1827 – April 22, 1895) was a French artist, astronomer and amateur entomologist.[1][2] He is noted for the import and release of the spongy moth into North America. The spread of the moths as an invasive species has resulted in the destruction of millions of hardwood trees throughout the eastern United States.[citation needed]

Biography

[edit]Trouvelot was born at Aisne, France. During his early years he was apparently involved in politics and had republican leanings.[citation needed] Following a coup d'état by Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte in 1851, he fled with his family to the United States. They settled in the town of Medford, Massachusetts, a suburb of Boston, at the address of 27 Myrtle St. There he supported himself and his family as an artist and astronomer.[3]

Trouvelot had an interest as an amateur entomologist. In the U.S., silk-producing moths were being killed off by various diseases. Trouvelot was very interested in Lepidoptera larvae including native North American silk moths which he believed could potentially be used for silk production. For reasons that remain unknown, Trouvelot brought some spongy moth egg masses from Europe in the mid-1860s and was raising spongy moth larvae in the forest behind his house. Unfortunately, some of the larvae escaped into the nearby woods. There are conflicting reports on the resulting actions. One states that despite issuing oral and written warnings of possible consequences, no officials were willing to assist in searching out and destroying the moths.[4] The other notes that he was aware of the risk and there is no direct evidence that he contacted government officials.[5]

Shortly following this incident, Trouvelot lost interest in entomology and turned again to astronomy. In this field he could put his skills as an artist to good use by illustrating his observations. His interest in astronomy was apparently aroused in 1870 when he witnessed several auroras.

When Joseph Winlock, the director of Harvard College Observatory, saw the quality of his illustrations, he invited Trouvelot to join the staff there in 1872. In 1875, he was invited to use the U. S. Naval Observatory to use the 26-inch refractor for a year. During the course of his life he produced about 7,000 quality astronomical illustrations. Fifteen of his most superb pastel illustrations were published by Charles Scribner's Sons in 1881. He was particularly interested in the Sun, and discovered "veiled spots" in 1875. He was elected a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1877.[6]

Besides his illustrations, he published about 50 scientific papers.

By 1882, Trouvelot had returned to France and joined the Meudon Observatory where he worked with photography and became engaged in a bitter rivalry with his boss, the astronomer Jules Janssen.[7] This was a few years before the magnitude of the problem caused by his spongy moth release became apparent to the local government of Massachusetts. He died in Meudon, France. The spongy moth was considered a serious pest and attempts were underway to eradicate it (ultimately these were unsuccessful). To this date, the spongy moth continues to expand its range in the United States, and together with other foliage-eating pests, cause an estimated $868 million in annual damages.[8]

Awards and honors

[edit]- Valz Prize by the French Academy of Sciences

- The crater Trouvelot on the Moon is named after him.

- The crater Trouvelot on Mars is named after him.

See also

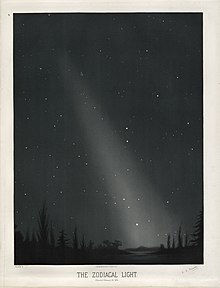

[edit]Gallery

[edit]-

Leonid meteor shower, 1868

-

Aurora Borealis, 1872

-

Saturn, 1874

-

Orion nebula, 1875

-

Moon, 1875

-

Mars, 1877

-

Jupiter, 1880

References

[edit]- ^ Onion, Rebecca (January 21, 2015). "Beguiling 19th-Century Space Art, Made by a Self-Taught Astronomical Observer". Slate (blog).

- ^ Étienne Léopold Trouvelot’s Stunning 19th-Century Astronomical Drawings of Celestial Objects and Phenomena

- ^ Jimena Canales, A Tenth of A Second: A History (Chicago University Press, 2011)

- ^ The Gypsy Moth: Research Toward Integrated Pest Management, United States Department of Agriculture, 1981

- ^ Watson, A., Fletcher, D.S. & Nye, I.W.B., 1980, in Nye, I.W.B. [Ed.], The Generic Names of Moths of the World, volume 2 © Trustees of the British Museum (Natural History), Publication Number 811 ISBN 0-565-00811-0

- ^ "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter T" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved September 11, 2016.

- ^ Jimena Canales, A Tenth of A Second: A History (Chicago University Press, 2011)

- ^ ""Economic Impacts of Non-Native Forest Insects in the Continental United States" at Journalist's Resource.org".

External links

[edit]- Trouvelot Astronomical Drawings at the NYPL Digital Gallery

- Trouvelot Astronomical Drawings vs. NASA Images at the NYPL Digital Gallery

- Trouvelot: Moths to Mars

- AAS biography

- Gypsy Moth In North America

- Trouvelot Astronomical Prints Collection, Princeton University Library, 2004

- Pictures of electric sparks and lightning bolts, chromolithographies of the Sun kept at the Library of Paris Observatory